Willey House Stories Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 3: Plagued By Fireplaces

Steve Sikora | Jan 20, 2023

In this seven-chapter subseries of the Willey House Stories, Steve Sikora reflects on Frank Lloyd Wright’s fireplaces, their purpose and meaning—and the search for one missing kettle. Subsequent chapters will follow over the next few weeks.

What began as a quest for the lost Willey House kettle led me on a tangential journey to understand why an iron cookpot would exist in the fireplace of a modern home at all. Surely Wright’s fireplaces must hold the key.

Fireplaces

Fireplaces have historically been employed in homes to provide: heat, nourishment and aesthetic pleasure. Let’s explore the usefulness of the fireplace.

The fireplace: a source of heat

A fireplace warms the home. Okay, stop there. Does it? A fireplace in any house, modern enough to be fitted with an integral heating system; be it steam, hot water, or forced air can’t be considered as a primary source of heat. Truth be told, that statement would have been just as honest one hundred and twenty years ago as it is today. Yet Wright never designed a house without one. No question, a wood-burning fireplace is often considered a supplemental heat source, but in most cases, they are far less efficient than any integrated boiler or HVAC system, and almost always tend to work in opposition to them. The efficiency problem with a fireplace is that it discharges a high volume of warm air from the house in the process of venting smoke up the flue. Inadvertently, room air with replenished, cold air from outdoors is drawn in through gaps around doors and windows. Heat radiating from the firebox is often overwhelmed by the amount of cool air drawn indoors when combustion gases and warm air are exhausted. To compound the problem, if the home’s thermostat happens to be in proximity to the fireplace at the core of the house, which it often is, it will respond to whatever radiant heat is produced in the immediate vicinity by plunging the extremities of the house into a deep freeze. The only contemporary wood burning fireplaces that produce significant warmth are those sealed behind radiant glass, contained so that they are fed with outside air, or have metal firebox inserts with plenums that capture heat and redirect it back into the room. Fireboxes with cast iron firebacks or those constructed from refractory firebrick do a better job of warming a space but still suffer from inefficiency.

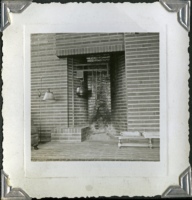

The kettle hung in the evidently well-used fireplace in this snapshot, circa 1937. Credit: Nancy Willey’s photo album

Period photos suggest Malcolm and Nancy Willey used their fireplace on a regular basis. The creosote glazed fireback and mounds of ash in photos bear that out. The back wall in the Willey House fireplace radiates an impressive amount of heat during a prolonged fire. It could have functioned spectacularly if only the throat was proportioned and vented in the manner of a true Rumford design. The tall, shallow Willey House firebox is reminiscent of a Rumford fireplace in form and proportion but falls shy of the mark from a technical perspective. In 1795 Benjamin Thompson aka “Count Rumford” revolutionized the wood-burning fireplace with his “perfected” design. Rumford sought to overcome the most common problems that plagued the fireplace, then the primary heat source. Even then, fireplaces often did not draw properly. Fireplaces did not heat efficiently. Fireplaces did not burn cleanly. He succeeded brilliantly with his paradigm shifting design.

Rumford’s reimagined fireplaces became the gold standard and remained so for over fifty years until the next wave of technical advancements in indoor heating superseded them. Mechanical heating systems killed the Rumford. Culturally, by the mid-nineteenth, century, due to the introduction of central heating, the fireplace was no longer a primary heat source. Even before Wright was born, this was the prevailing sentiment. Integrated heating systems relegated the fireplace to the stature of a quaint anachronism. No longer a day-to-day necessity, it wasn’t long before Rumford’s superior fireplace designs too faded into obscurity along with the masons who built them.

Wright almost certainly knew of Rumford and his fireplaces. So why didn’t he go out of his way to employ this superior technology even if it cost a bit more? Could it mean that Frank Lloyd Wright didn’t imagine his fireplaces to be a significant source of heat? Hard to say, but if the price of efficient heat and dependable draft meant slavishly adhering to a ridged set of proportional rules, that price was too steep. (Learn more about Rumford fireplaces at the end of this chapter.)

The enchanting Hanna House fireplace features a hanging fire basket, essentially a raised grate, as an attempted draft solution, for a fireplace made problematic by its own design. Credit: Steve Sikora

The troubles confronting Wright’s fireplaces, particularly those in his late career, are as various as his design configurations are imaginative. Consequently, you’ll find no universal treatment for their frailties. Though most functional defects can be overcome, each solution is likely to be its own. At the Seth Peterson Cottage, for example, an outside cold air vent was routed into a smoky hearth as a simple fix to improve the draft, a common sense solution. But not all countermeasures are so obvious. Improper firebox to flue proportions are difficult to overcome. I’ve seen more than one Usonian with a little wood stove retrofitted into its firebox by a frustrated owner—metal stovepipe shot up the chimney. An ill-advised but understandable reaction to what seems like an intractable problem. Unfortunately, this is an example of the worst kind of antidote. As homeowners know, or must suspect, many of Wright’s later fireplaces simply ignore the well-established rules of thumb which state; a properly functioning fireplace is the product of the size and shape of its opening, the volume of the firebox and the ratio between opening and flue. Period. (See the specific requirements for a properly functioning fireplace at the end of this chapter.)

Wright seemed to respect the rules of fireplace making early in his career but grew increasingly cavalier during the middle and second half. For example,Wright’s 1937 Hanna House living room fireplace, improvises a quirky redress to its own innate problematic design, namely a firebox that was so tall and unenclosed as to barely behave like a fireplace at all. Viewed in abstract it is almost a wire frame rendering of a physical object rather than a solid one, an idea not an object, a sort of hypothetical fireplace

The overall impression is of a well-preened child descended from wealth, too beautiful to work. It is a wide-open, decorative niche posing as a fireplace. To compensate for lack of containment, the contrivance Wright dreamed up was a hanging fire basket suspended from a fireplace crane. The basket effectively elevated the grate a foot or so above the sunken floor of the hearth. Even though this floating fire grate brought the fire a bit closer to the chimney flue, it was a rather small and precarious platform to balance logs upon. Even if the basket effectively suspended the blaze in mid air, the embers and ash from the consumed firewood inevitably fell through the grate and smoldered on the hearth floor, effectively defeating its purpose in improving the draft. Dare anyone actually attempt a fire in this space, which they did; a 240˚ wrap-around chainmail screen was added to prevent sparks from escaping the phantom hearth. Even more astonishing, early photos of the house show wall-to-wall carpeting running up to the very edge of the sunken fireplace steps. Using the fireplace must have demanded real courage and constant vigilance. For all its ephemeral charm and wonder this fireplace couldn’t possibly have produced a carefree fire for the family to gather round. Yet Paul and Jean Hanna made no mention of the practicality of this arrangement in their book, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hanna House; The Client’s Report they did however, indicate challenges they had with Wright’s absolute adherence to the hexagonal module. The kitchen, bathtub, hallways and beds all were constricted in some way that challenged their usefulness. The ravishingly flawed fireplace it appears, was yet another victim of the hexagonal unit. It’s worth noting that Wright under the Hannas guidance did include a second, utterly conventional fireplace in a later addition.

Spalled and cracked bricks removed from the fireback and hearth, during restoration of the Willey House fireplace. Credit: Steve Sikora

Stafford Norris mounted an induction fan at the top of the Willey House chimney to improve upon an undependable natural draft experienced there. It worked well for us, but an induction fan alone is a panacea that may not serve in all situations. Shape aside, a glitchy byproduct of Wright’s penchant for beauty over function in fireplace design is one of materials. Firebricks are special purpose, refractory bricks made from alumina and silica rich fireclays.

They are designed to withstand extreme heat and are graded for their heat resistance. The lightweight and porous texture of firebricks accord them with superior insulating properties. Heat is reflected outward rather than absorbed. Wright, however, insisted that the Willey House fireplace backing be constructed of the exact same bricks used in the composition of the house. The same red bricks used for inside and outside walls, floors, terrace and yes, fireplace. Upon learning that the mason had set firebricks inside the hearth, Wright demanded them immediately torn out and replaced. Predictably, over a period of years, the bricks on the walls and floor of the hearth overheated and spalled off in flakes. In Wright’s opinion, I suppose, that was a price worth paying for the striking continuity of a single, plastic material, in this case, red brick, folding around corners, conjoining walls to floor and extending from inside the house to the garden, flowing beneath the bank of French doors. In his mind, it seems, a degree of material failure was a fair trade for the sake of aesthetic purity.

Lloyd Lewis, a good friend of Wright’s complained incessantly about his smoky fireplace. He was admonished to stand his wood on end, and I don’t think it was meant as a lewd metaphor.

Custom-made firebricks mortared in place, were created to resemble the original standard red bricks. Credit: Steve Sikora

Literally Wright expected Lewis to prop his logs upright against the fireback. To chide a client for not balancing their firewood on end, hardly explains a fireplace that is reluctant to draw, when in all honesty, an apology was in order. Lewis wasn’t alone. Wright sometimes counseled clients, certain fireplaces were meant for burning logs vertically when the draft was poor. It reminds me of Steve Jobs, who famously told early iPhone users “You’re holding it wrong!” claiming that reception problems with the iPhone 4 were due to customers holding their inorganic devices incorrectly. Good design is meant to be accommodating not alienating. If the shape of a smart phone becomes a rectangle for aesthetic purposes, its lack of ergonomics leaves its handhold wide open to human interpretation. By extension, when designing a fireplace, make it so the smoke from stacked firewood, however it may be arranged, drafts up the chimney. Like Jobs, Wright was ignoring his responsibility in the matter. For those unfamiliar with fires, you can stand logs vertically, and you can burn logs, but you can’t dependably do both. Even when a vertical fire is lit, eventually standing wood will fall, which makes it no different than horizontal wood, laid on a grate.

By citing so many negatives am I suggesting that Wright’s fireplaces were failures? Hardly. In fact, I believe his fireplaces are transcendent; including what might be the mother of all primordial hearths, the fireplace at Fallingwater. But Wright’s fireplaces, specifically those in the later part of his career, do have occasional shortcomings. Perhaps their flaws are no different than Wright’s over optimistic engineering of a cantilever. Just like in his botherations of engineering, some fireplaces require remedial intervention. So then, can we honestly say functionality was a concern for Wright?

As we know, actions speak louder than words. Wright’s spacious fireplace openings come in a cacophony of shapes, depths and sizes. His masonry awnings and expansive fireboxes simply offer wood smoke too many alternatives to a trip strait up the flue. Furthermore, a concession to the use of actual firebricks certainly would have helped his fireplaces radiate more heat, yet he often declined. Still, his apparent actions may not speak the whole truth. Maybe he thought of perfected utility as an occasional bonus that accompanied his designs rather than an expectation.

Credit: Steve Sikora

There must be more behind Wright’s intentions because the man certainly knew how to build a decent fireplace. Yet, here they are, his fireplaces, for all their unrivaled beauty, seem unencumbered by the expectation of flawless functionality.

As his art and philosophy matured, Wright’s fireplaces began to reflect the same dramatic advancements and simplifications achieved in his architecture. His designs became progressively stripped down to the bare geometric essentials. Fireplaces, like the homes constructed around them, evolved to become more organic in nature, simplified, more doggedly adherent to the unit grid, more plastic, open and free flowing. Above all, his fireplaces were superbly integrated into the design of his homes. They contributed greatly to his goal of creating total continuity and an organic whole. End of story, for now.

Afterword

Glossary:

The parts of a fireplace from bottom to top are:

Hearth – the floor of the firebox

Fire grate – the metal rack the holds logs above the hearth

Fire basket – a hanging fire grate

Firebox – the space inside is fireplace where combustion takes place

Fireback – the back of the firebox

Opening – the rim of the firebox

Lintel – the top edge spanning the opening

Breast – the upper back of the firebox that slopes forward

Throat – the top of the firebox behind the lintel

Damper – the trap door between firebox and flue

Smoke Shelf – the flat masonry shelf at the bottom of the chimney at damper level to check down drafts

Smoke Dome – the tapering masonry side and front walls to join fireplace with chimney

Flue – the inner chimney

Refractory Panels – sides and back of a firebox made of heat resistant material designed to reflect heat back into the room

Sections of a fireplace from bottom to top are:

Combustion chamber – includes the extended hearth, firebox, masonry surround and throat

Smoke chamber – includes the damper, smoke shelf and smoke dome

Chimney – includes the flue

The scale of a fireplace is relative to room size, but general proportions are consistent.

To achieve relatively smoke-free fires and consistent draw, the time-tested proportions of a fireplace are:

- A standard opening of 24-36 inches wide, and 24-29 inches high

- A depth of 16 inches

- A distance from the hearth (floor) to the damper of about 37 inches

- A rear width of the firebox of 11 – 19 inches

- A fireback that slopes forward beginning 14 inches above the hearth floor

- The flue in chimneys 15 feet high and over should be 1/8th the total opening of the fireplace. Fireplaces with two or more open sides required totaling all sides of the opening. (For chimneys 15 feet or shorter the ratio is 1/10th.)

Chimney height as well as nearby obstructions may also effect the ability of a fireplace to draw.

The Rumford Fireplace

In 1795 Benjamin Thompson aka “Count Rumford” revolutionized the wood-burning fireplace with his “perfected” design.

He sought to overcome the most common problems that plagued fireplaces:

- Fireplaces would not draw properly

- Fireplaces would not heat efficiently

- Fires would not burn cleanly for lack of fresh air

Rumford understood there were 3 types of heat transfer caused by fire:

- Radiation – the emission of heat via energy waves

- Convection – the transfer of heat by the physical movement of hot air

- Conduction – the transfer of heat within a material

And he deduced most of the usable heat produced by a fireplace was radiant heat. Based on that premise Rumford reinvented the fireplace specifically to better radiate heat into a room.

By way of definition, Rumford fireplaces are typically taller and shallower than “conventional” (pre 1795 and post 1850) fireplaces. The first significant differentiator is their refractive fireback. The shallow Rumford fireboxes have straight rather than sloping firebacks. Their widely angled covings direct heat broadly in a wide angle. Second, Rumfords are designed with a rounded airfoil throat. It behaves like the pinch-waisted venturi in a carburetor. This innovation increases the velocity of air drawn up the flue. Consequently, Rumford fireplaces draft far better than conventional designs and burn wood cleanly. Rumford’s intuitive redesigned fireplaces drafted like a jet, long before thermal dynamics could prove his methodology. The Willey House fireplace has that same familiar straight, tall fireback with angled covings and could have been a successful Rumford design if only a rounded breast had been added at the throat and if the fireback was laid up in refractive fire brick instead of the same red brick used everywhere in the house. Wright designed many tall shallow fireplaces. But if any of them qualified as a full-fledged Rumford design I have not seen it. In a few instances Wright suggested that the fireplace was intended for burning logs vertically. Some Rumfords did burn standing logs. But neither Wright nor Rumford seemed to acknowledge that standing logs sooner or later are consumed and fall down. So the design had better not depend on the elevation of the log to draft properly.

Like conventional fireplaces Rumfords also draft warm air out of the house but as a trade-off they project a significant amount of radiant heat into the room with many times the efficiency of modern fireplaces.

Most fireplaces built between 1796 and 1850 were Rumford fireplaces. Ironically, after 1850 with advancements in indoor heating systems the fireplace was slowly relegated to a more ornamental status. No longer a primary heat source by 1850 Rumford fireplaces became less common and by the 1900’s, most masons forgot or never learned how to build a proper Rumford fireplace. The amnesia of the perfected fireplace was brought on by the boiler and was exacerbated by the furnace. Design improvements that perfected the ills of the fireplace were lost along with the masons who understood how to construct them. An excellent resource on Rumford fireplaces can be found online at the Rumford.com.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains

Part 14: Separated at Birth

Part 15: Trading Drama for Poetry

Part 16: A Red By Any Other Name

Part 17: Roll Down to Levittown

Part 18: Cherokee Red The Rejoinder

Part 19: Nothing Lasts Forever

Part 20: The Struggle

Part 21: Giving What They Had to Give

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 1: The Kettle

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 2: The Crane

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 3: Plagued By Fireplaces

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 4: A Heritage of Cooking Fires

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 5: Benefits of the Fireplace

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 6: Transcendental Flame

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 7: Repatriation