Willey House Stories Part 6 – Little Triggers

Steve Sikora | Jun 12, 2018

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

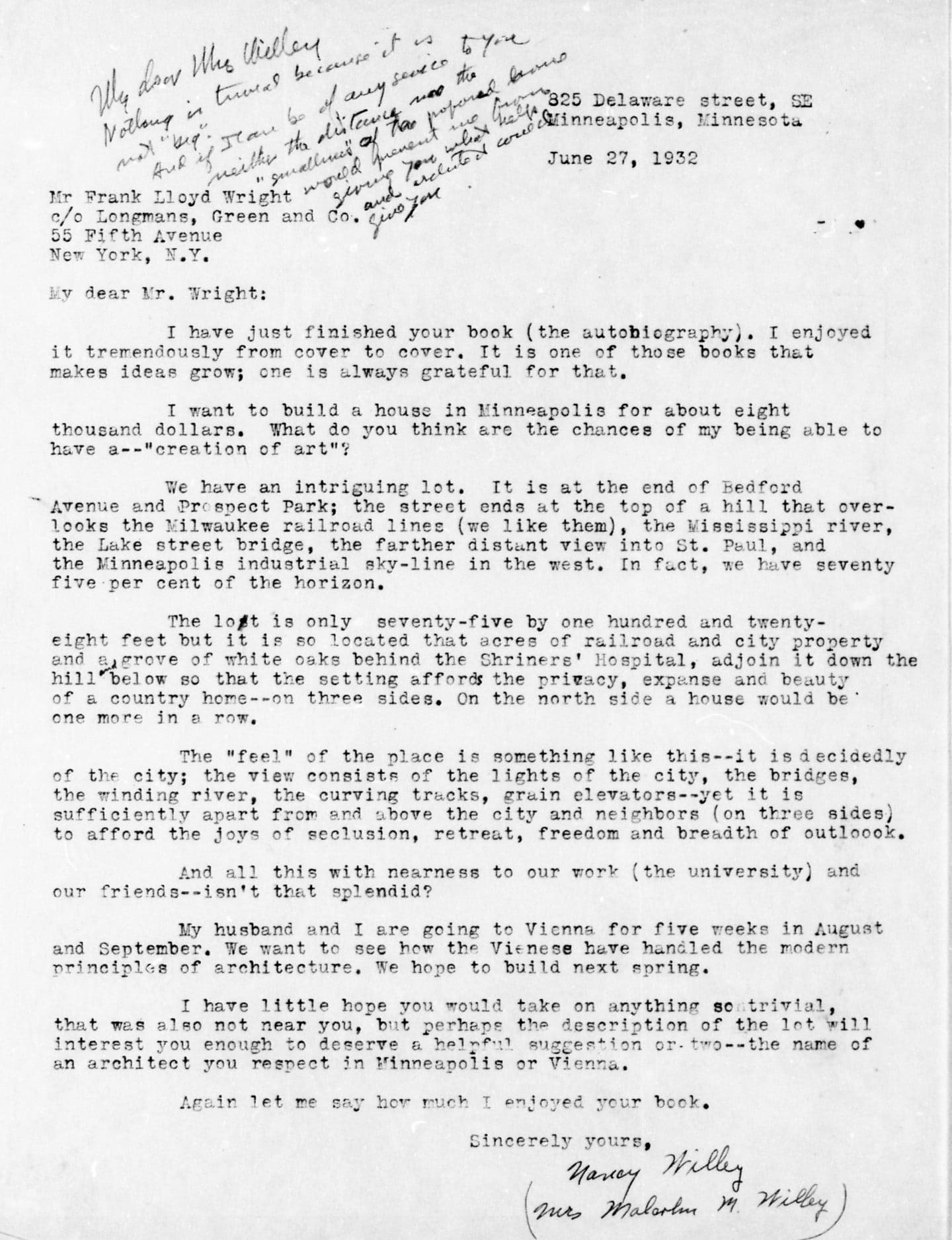

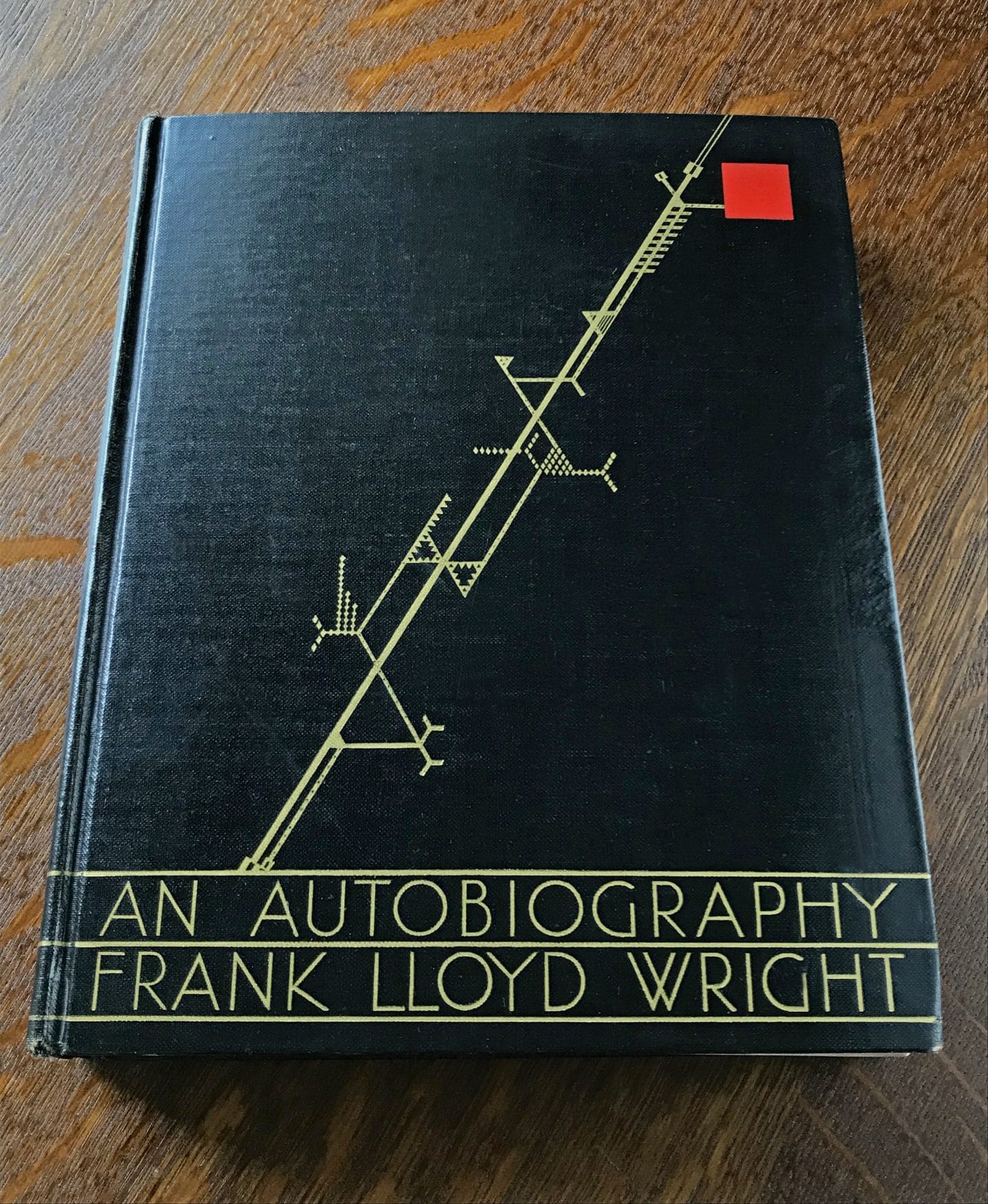

The initial exchange between Nancy Willey and Frank Lloyd Wright should rank high on the imaginary list of most seductive business correspondence ever committed to paper. In the early years of the Great Depression, Malcolm and Nancy Willey were just another a young faculty couple at the University of Minnesota, but when Malcolm entered the administration and his status steadily rose, they found themselves in the market for a home of their own. Nancy was considering the advice of her hairdresser, who advocated for contacting a local builder that specialized in catalog houses, when Malcolm brought home the first copy of Wright’s An Autobiography from the university bookstore. According to Nancy, the ideas it contained sent them both sky high! In a moment of youthful exuberance, she reached out to Frank Lloyd Wright, to ask him to design a small house in Minneapolis.

825 Delaware Street, SE

Minneapolis, Minnesota

June 27, 1932

Mr Frank Lloyd Wright

c/o Longmans, Green and Co.

55 Fifth Avenue

New York, N.Y.

My dear Mr. Wright:

I have just finished your book (the autobiography). I enjoyed it

tremendously from cover to cover. It is one of those books that

makes ideas grow; one is always grateful for that.

I want to build a house in Minneapolis for about eight thousand

dollars. What do you think are the chances of my being able to

have a–“creation of art”?

We have an intriguing lot. It is at the end of Bedford Avenue and

Prospect Park; the street ends at the top of a hill that overlooks the

Milwaukee railroad lines (we like them), the Mississippi river, the

Lake Street bridge, the farther distant view into St. Paul, and the

Minneapolis industrial sky-line in the west. In fact, we have seventy-five

percent of the horizon.

The lot is only seventy-five by one hundred and twenty-eight feet but

it is so located that acres of railroad and city property and a grove of white oaks behind the Shriners’ Hospital, adjoin it down the hill

below so that the setting affords the privacy, expanse and beauty of

a country home–on three sides. On the north side a house would be

one more in a row.

The “feel” of the place is something like this–it is decidedly of the

city; the view consists of the lights of the city, the bridges, the

winding river, the curving tracks, grain elevators–yet it is sufficiently

apart from and above the city and neighbors (on three sides) to

afford the joys of seclusion, retreat, freedom and breadth of

outlook.

And all this with nearness to our work (the university) and our

friends–isn’t that splendid?

My husband and I are going to Vienna for five weeks in August and

September. We want to see how the Viennese have handled the

modern principles of architecture. We hope to build next spring.

I have little hope you would take on anything so trivial that was also

not near you, but perhaps the description of the lot will interest you

enough to deserve a helpful suggestion or two–the name of an

architect you respect in Minneapolis or Vienna.

Again let me say how much I enjoyed your book.

Sincerely yours,

Nancy Willey

In response:

Mrs. Malcolm M. Willey,

825 Delaware Street,

Minneapolis, Minn.

My dear Mrs. Willey:

Nothing is trivial because it is not “big.”

And if I can be of any service to you neither the distance nor the

“smallness” of the proposed home would prevent me from giving

you what help an architect could give you.

Sincerely yours,

Frank Lloyd Wright

July 5th. 1932.

Over the years, we’ve shared these opening letters with visitors to the Willey House. On the surface, they are remarkably poetic for business correspondence by the standards of the time, or really any other time. Both letters exhibit a conscious romantic flair. However, the more often I read them, the more I began reading between the lines. It is clear that Nancy possessed considerable powers of persuasion, and did her level best, to beguile Wright. While his prompt and charming response is a textbook example of how to “keep a live-one on the line,” note the speed of his reaction. Only eight days elapse between the date of Nancy’s inquiry and Wright’s response, even though she writes to his book publisher in New York who must forward her letter to Taliesin in Spring Green.

Frank Lloyd Wright is in dire need of a commission and Nancy’s letter is a tour de force of enticements. Its short pages contain an astounding number of triggers, any one of which might successfully prompt the great architect, to accept her small commission, some are decidedly intentional, while others equally compelling, may be credited only to fortuity.

1.

Wright needs paying work

This first point seems obvious. 1932 marks the middle of the Great Depression and the economic horizon seems bleaker than ever. Like so many other Americans, Frank Lloyd Wright had no cash flow. Only months prior to Nancy’s letter, Olgivanna wrote to Frank’s sister, Maginel Wright Barney, in New York pleading with her to send them $30. It is doubtful that Nancy was aware of his grave financial situation, given another legendary story regarding the Willey’s visit to Taliesin when it is revealed to them that Wright has no active commissions but their own. The burden of Wright’s financial obligations certainly weighed heavily on him. But desperation alone may not have driven him to accept a commission he did not want. He once advised his son, John Lloyd Wright, “An architect must have the courage to turn away a commission even if he is hungry if his work will not represent his highest ideals. No building has the right to be erected unless it is the working out of some idea, the practical demonstration of some principal at work.” Which brings us to point number 2.

2.

A “creation of art”

Nancy Willey presented her modest budget and immediately followed up with a request sure to entice the romantically inclined artist when she asks for “a creation of art.” How could Wright resist such a thing? No reading of An Autobiography could leave doubt as to the artist, his artistry or his passion to create a thing of beauty.

3.

Stroking Mr. Wright’s ego

Nancy gushes at the beginning, and end of her letter as to how “tremendously” much she enjoyed An Autobiography. She calls it the kind of book that “makes ideas grow” as a preamble to her actual request. Given the national press stories characterizing Wright’s justifications for his sensationalized, lurid, personal affairs it is likely she had some awareness of his outsized ego and intuited what might be required to stimulate it.

4.

An alluring site description

Nancy explains she and Malcolm purchased a lot, and to fire Wright’s imagination, spends 211 words describing it in luscious detail. An Autobiography would have helped inform the sort of site that might appeal to Wright, in particular, the hillside that his own home, Taliesin gently wraps itself around, “I knew that no house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. House and hill should live together each the happier for it.” Nancy describes the lot she and Malcolm purchased in Prospect Park, through the lens of someone who, herself is infatuated.

Cover of 1932 Edition of An Autobiography. Photo by Steve Sikora.

5.

The recommendation of another architect he respected

Frank Lloyd Wright was a notorious public figure with a reputation for believing he was the greatest architect who ever lived (or whoever would live). He did not go out of his way in the first edition of An Autobiography to express much admiration for his peers other than Louis Sullivan. Is it possible she really believed he’d recommend another architect, even if he did respect one? Perhaps her question was intended to give Wright an easy way to bow out, knowing he could make no such recommendation? Or did she sense that by asking for his recommendation, he’d quickly come to the conclusion that he’d better just do it himself?

6.

Could he recommend a European architect?

In his autobiography, Wright alludes to a fortuitous visit from Kuno Franke, professor of aesthetics, which he believed, led to his invitation to publish the Wasmuth Portfolio in Germany. But he makes no mention of the rising wave of European Modernism in An Autobiography. So, it is doubtful that Nancy understood his feelings on the subject much less leveraged them. However, after feeling snubbed by Philip Johnson and Russell-Henry Hitchcock, curators of the 1932 MoMA show on the International Style, Wright was still nursing his wounded pride at the time of Nancy’s letter. Internationlist J. P. Oud, unfaithful, former draftsman Richard Neutra, and compound architect, Walter Gropius, as Tom Wolfe labeled him, in From Bauhaus to Our House, were Wright’s nemeses, Europeans all. He would have moved to prevent any one of them from building so much as a birdhouse on American soil. Frank Lloyd Wright felt as isolated and forgotten at the outset of this European invasion, as Elvis during the British invasion, when the American charts were suddenly crowded with back-to-back hits by the Beatles, Stones and Kinks, seemingly damned to a future of prescription bottles and fried peanut butter sandwiches.

7.

The Willey’s proposed trip to Vienna

Exactly one line in An Autobiography expresses Wright’s affection for Austria. “Vienna had always appealed to my imagination. Paris? Never!” However, Anthony Alofsin’s book The Lost Years sheds much needed light on Wright’s time in Europe, ostensibly working on publication of his Wasmuth Portfolio, while simultaneously in exile with Mamah Borthwick Cheney. Contrary to popular reportage, including Wright’s own, influences between the architect and Europe flowed in both directions. He was in fact, strongly taken by the Vienna Secession Movement. Wright extensively collected Secessionist prints. It was in Europe where he was inspired to explore asymmetrical design and learned how to conventionalize the human form, courtesy of Sessionist models. Wright developed an admiration for and the friendship of Joseph Maria Olbrich. Wright was even called “the American Olbrich”. The Vienna Secessionists, like himself, attempted to sever the bonds of Historicism in architecture. It is highly unlikely she was aware of his affection for this particular European movement. But perhaps the prospect of being upstaged by architects he admired, was equally threatening as losing work to those he did not.

8.

Why did Nancy, rather than Malcolm, write the letter?

A simple explanation for “Why Nancy?” is that it could have been a calculated gesture, given Wright’s public reputation as a “ladies’ man”. It may have seemed advantageous to the Willeys, that Nancy, a woman, make the inquiry.

But this is a complicated question. Certainly it would have been more commonplace in the thirties, for the husband to initiate a business contact. After all, the house was paternally named the Malcolm Willey House. One possible explanation is a theme that subtly emerges as a subtext in Nancy’s later life interviews. There was a tacit understanding that seemed to exist between Mr. and Mrs. Willey that in exchange for putting aside her career to help advance his, she be given full control over the planning of their new home. The best evidence is in the fact that she authors nearly every missive to Taliesin over a period of more than decade.

Long after the fact, Nancy mused that Malcolm thought her introductory letter to Frank Lloyd Wright to be “full of McGuffey,” in reference to McGuffey Readers, the standard primers for grades 1 through 6 used from 1836 to 1960. His remark teasing that he judged her request to be either elementary or overly didactic. If either were true, the result could not have been more favorable. Wright promptly agreed and Nancy carried the conversation. Smart but utterly inexperienced in these matters, Nancy was required to be an excellent communicator in order to live up to the supervisory role she played in the building of the home.

It is impossible to know, but easy enough to imagine, if Malcolm had written the first letter, that it would have been more academic in tone. Still, it is hard to dispute the efficacy of the fusillade of temptations that Nancy unleashed upon Wright in hers. Nancy’s letter is like the pre-dawn, plaintive cry of a songbird in spring. She is not merely attempting to coax an acceptance from Wright so much as seducing him to beg her for the commission.

9.

Nancy Willey’s request was presented in the form of a clearly stated idea

Nancy Willey said, “I got want I asked for and liked what I got”. Her vivid description of their small lot at the end of Bedford, and in particular, the vista it offered was clearly articulated in her request. Wright visited the site before construction to see for himself. Indeed, there in her first penned lines to Frank Lloyd Wright was the basis for the idea he sought to preserve throughout the process of designing two consecutive residences for Nancy, until he got it right and the vista was at last hers.

View from lot at end of Bedford Street SE. Photo courtesy of Nancy Willey’s photo album.

10.

A challenge

The final incentive can only be inferred by the description of the clients themselves. Among Frank Lloyd Wright’s many career-long quests was a desire to seek solutions for well-designed, affordable housing. 20 years prior, he had conceived of the standardized, American System-Built Houses with developer, Arthur L. Richards in order to provide beautiful homes for the many. 20 years later, Wright consented to design an Arizona trailer park with a mere $250 budget, for Lee Ackerman.

We can’t know for sure whether the Willeys sensed his proclivity while reading An Autobiography. But one thing is certain, because this particular theme is repeated throughout his career – an opportunity to surmount the challenge of well designed, low-cost housing, through the design of a small house for a couple of ordinary means, might have been the most appealing draw of all. Rather than simply a reaction to a client’s desires, this lofty ambition speaks to the very truth of who Frank Lloyd Wright was, an architect intent on defining a democratic landscape deserving of all Americans.