Willey House Stories Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 1: The Kettle

Steve Sikora | Jan 6, 2023

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

In this seven-chapter subseries of the Willey House Stories, Steve reflects on Frank Lloyd Wright’s fireplaces, their purpose and meaning—and the search for one missing kettle. Subsequent chapters will follow over the next few weeks.

I dip my cup of soup from a gurgling

cracklin’ cauldron in some train yard.

My beard a rustling, cold towel, and

a dirty hat pulled down across my face.

Through cupped hands ‘round a tin can

I pretend to hold you to my breast and find.

that you’ve been waiting from the back roads

by the rivers of my memories

ever smilin’ ever gentle on my mind.

– Gentle On My Mind, John Hartford

To my way of thinking, the wistful John Hartford tune, Gentle On My Mind is far more than a skillful exercise in song craft. His noteworthy composition is the direct expression of a universally relatable emotion—the comfort provided by a warm cup shared around an open fire.

Oddly compelling and artfully told, the hope-soaked melancholy evoked by the song is largely derived from little more than Hartford’s poignant description of an ordinary cooking pot, played out plinking banjo time.

The delicious sentiment he served up so well does not require surviving the hunger of homelessness, dwelling in the wilderness or having paid one’s dues in a cold, dirty train yard. Because, a “gurgling, cracklin’ cauldron” suspended over a crude campfire is no more or less gratifying than one gracefully poised on a sturdy hook in a comfortable domestic setting. The visceral experience of a simmering kettle wherever it may be found, represents a deep, simple human sense of welcome, warmth and succor. This is the story of one such kettle.

Photo by Steve Sikora

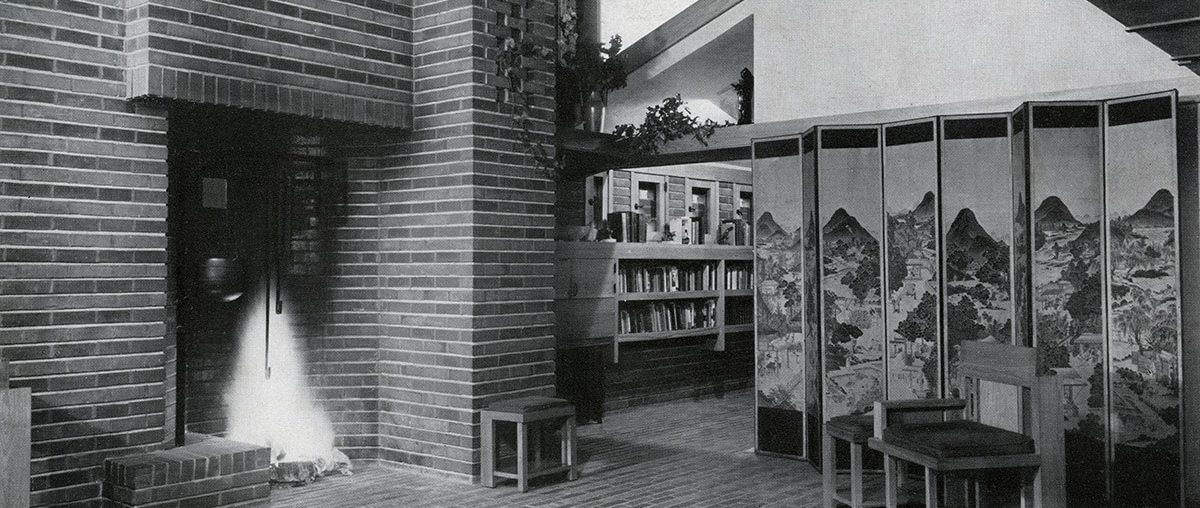

Malcolm and Nancy Willey’s daring new house was debuted to the architectural community and the world at large in the January 1938 Architectural Forum. It was a publication dedicated to the recent work of Frank Lloyd Wright. The entire spiral-bound issue was written and designed by Wright, and produced with the assistance of his recently established Taliesin Fellowship. On page 30 of the magazine, there appeared a particularly beguiling, full-page image of the Willey House living room. As with the other houses illustrated in the magazine, the photo was expertly framed by the Chicago firm of Hedrich-Blessing. I latched onto the iconic interior scene as a source of inspiration at the time we acquired the Willey House—then a forgotten masterpiece in a murky state of willful neglect and consequent, utter disrepair.

The Willey House living room photo by Hedrich-Blessing featured in the January 1938 Architectural Forum. Credit: Hedrich-Blessing, Chicago Historical Society

In a letter to Nancy dated October 19th 1937, Wright’s secretary Eugene Masselink announced (not requested) that Kenneth Hedrich a photographer from Chicago “…will be coming to Minneapolis sometime this weekend to photograph your house.” Mrs. Willey reacted with her usual unconditional enthusiasm and afterword, giddily reported that “Tuesday and Wednesday Kenneth Hedrich and Earl Gerlach were here with amazing equipment.” She verified her willing participation with, “It was very interesting to watch them work. There was one moment when we had stripped the beds of five blankets for the purposes of holding back the sun!”

Notable details in this elegantly composed tableau are; the silhouette of a glazed Nakoma statuette strategically posed on a floating deck above the gallery, an elegant 8-panel Korean screen covering an entire wall and a blaze illuminating the open hearth. The first two items have been the subjects of previous stories. Completing this idyllic portrayal of Wrightian domesticity is a round-bellied pot hanging from the fireplace armature—a ribbed, three-legged black kettle to be exact. The kettle appeared in a number of published and unpublished photos from this era, yet it was absent when we took possession of the house in 2002. The third owner, Harvey Glanzer, had instead hung two other, odd lot kettles from the irons during his tenure; one, an unbecoming, enamel-lined, cast iron bucket and the other, a sorely abused copper pot, neither befitting the room, even at this, its lowest ebb.

The swiveling Willey House fireplace arm, an extrapolation of one found in Taliesin’s living room, anticipated the magnificent design he would soon create for Fallingwater. At the Willey House, the fireplace crane plan did not include a Wright-designed vessel. Instead, like most of his fireplaces, including the one in his own living room at Spring Green, the fireplace featured a pivoting crane that could convey any pot with a hoop handle over an open flame ostensibly for the purpose of “cooking.” Wright’s addition of a mobile arm was a subliminal reminder that the hearth fire was a provider of nourishment and warmth, a self-contained satisfier of creature comforts.

My attempt at understanding Wright’s rationale for a fireplace kettle in a modern living room prompted me to examine the three inter-related aspects of an indoor cooking fire: the kettle, to be sure, the crane that suspends a kettle over the flame and the fireplace that houses both crane and kettle. The kettle is addressed below, the crane in chapter 2 and the fireplace beginning in chapter 3.

The Willey House fireplace April 2002. Credit: Steve Sikora

The Kettle

The style of cooking pot depicted in the Architectural Forum is variously referred to as a cast iron pot, stew pot, bean pot, stockpot, Gypsy pot, cowboy kettle, cauldron or Dutch oven, especially if it is equipped with a concave lid to hold embers. I prefer the all-encompassing term kettle.

From the outset, I wondered where exactly, this marvelous iron kettle came from? I’ve found no recorded mention of it being sent from Taliesin, and if not from there, then from where? For a while, I believed the kettle was a gift to Malcolm and Nancy, sent by her parents in Sag Harbor, a historic whaling Village on New York’s Long Island. I don’t know why I believe this. I can’t locate any reference to my claim. Perhaps it was an apocryphal story conveyed. Or maybe Nancy mentioned it offhandedly in an interview. I suppose I embraced the idea because the kettle’s form is somewhat reminiscent of a whaler’s three-legged try pot (try-pot, trypot, tripot), used to render whale blubber down to lamp oil, only in miniature.

Whaling try pot. Akaroa, South Island, New Zealand. Credit: Michal Klajban, Wikimedia Commons

Why a try pot? The Annie Cooper Boyd House, once Nancy’s family retreat, and now home to the Sag Harbor Historical Society, is a 18th century Victorian cottage in old Sag Harbor. This was the setting for Nancy Willey’s (nee Boyd’s) Arcadian childhood summers. The romantic heritage of the whaling era possessed the Boyd family and later drew Nancy back to her native, seaside community where preserving the memories and places of whaling culture preoccupied the remainder of her life.

The premise of the kettle as a childhood remembrance is to some degree supported in a profile piece entitled, Sag Harbor Is Their Hobby, printed in The Minneapolis Star Tribune on Sunday, September 18, 1949. It highlights the annual summer trips that Malcolm and Nancy made to Sag Harbor and confirms the Willeys’ mutual enthusiasm for the region’s whaling past.

It has pleased Nancy and Malcolm Willey to prove that after all, “people can eat history.” The revived interest in Sag Harbor’s whaling past has almost turned it back into a boomtown. Real estate values have bounced up. Tourists pour in. Jobs are available again.

Malcolm was also enamored with the maritime past, “While Nancy Willey has helped bring fame and a modicum of prosperity to Sag Harbor buildings, Willey himself has enjoyed vacation research into uninvestigated portions of whaling history.” This was accomplished over several summer seasons. “Results of his research are published in a meaty little magazine called the Long Island Forum of which he is contributing editor.”

The crane in the fireplace of the Taliesin living room. Note the similarities between it and the one at the Willey House. Credit: Steve Sikora

If the kettle indeed were a gift or a souvenir, acquired from back home, this iron pot would have been a daily reminder of Sag Harbor for Nancy in far off, and decidedly landlocked Minnesota. Undeniably, it was the perfect complement to the fireplace Wright created. Apparently, he thought so too because similar kettles exist dangling from fireplace cranes at both Taliesins, as well as other Wright designed houses. Maybe it was a try-pot, maybe not. Barring proof to the contrary it still seems a likely relic of Sag Harbor. But that does not answer the next most pressing question, where in God’s name did that lovely old thing go? For twenty years I periodically attempted to discover the kettle’s origins as well as its final disposition. And for twenty years all efforts proved futile, yielding nothing but speculation and dead ends, until recently.

Long has the cauldron lingered in the back of my mind, nagging me. At one point, I noticed a photograph of a kettle that looked similar to the one that once graced the Willey House fireplace. It was definitely made of cast iron and flaunted the same distinctive ribs around its girth. But this iron kettle, clad in a patina of rust, was suspended on a trammel bridging the fire grate in Frank Lloyd Wright’s private residence at Taliesin West. Could Nancy Willey have re-gifted her kettle to Wright after she left Malcolm and her cherished home in Minneapolis? There seemed some strange logic to the possibility of that, and it required looking into. With a kind assist from Jeff Goodman at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation I was able to get a better sense of the kettle in Wright’s living quarters. The dimensions of the Taliesin West pot were 9 ¼” in diameter measured at top lip by 8” in height, a little smaller in scale than what I expected the Willey kettle to be. Hmm. Like so many artifacts in historic places, the provenance of this rusty pot was unknown. The only possible clue to its origin was the marking at the bottom of the bowl that read: “ALBERT MFG CO.”

The garden room fireplace at Taliesin has an identical crane to the one in the living room. Credit: Steve Sikora

In the Wright’s living quarters at Taliesin West hangs a kettle similar to the one shown in period photos of the Willey House. Credit: Jeff Goodman

I learned the Albert Manufacturing Company was one of a host of small, regional foundries in the business of making cast iron cookware in the early 20th century. There were hundreds of them. The company located in Los Angeles, California cast these distinctive round, three-legged kettles as well as anvils, mortar and pestles, iron planters and a cast iron camp stove. I’ve located a few examples of the Albert iron pots online, usually referred to as a “gypsy kettle,” or a “cowboy bean pot.” None were manufactured in service of the whaling trade and all were cast a century too late. The kettles I found online almost always measured 9 ½” in diameter and 7” high, even smaller than the one at Taliesin West. But the resemblance of the Taliesin West kettle to our lost one was strong. Could that rusty iron relic have been a gift from Nancy Willey?

Instead of a crane the Taliesin West kettle hangs from a trammel. Credit: Jeff Goodman

That annoying question was answered one day when I was confronted with evidence that thoroughly doused my fragile “gift theory” with cold water. Paging through a 1969 issue of Northwest Architect, there in a photo of the Willey House fireplace, hanging from the irons was the original kettle, plain as day. It was verified by a time stamp of the publication date. My accidental discovery once and for all snuffed out the notion that somehow the Willey kettle found its way to Arizona. The house in 1969 was owned and occupied by Russell and Jane Burris along with their three young children. If nothing else, the evidence ruled out countless possibilities. Because it confirmed the elusive kettle was not snatched from the irons by Nancy Willey. Not when she and Malcolm divorced in 1953. Nor did Malcolm remove it, when he sold the house, before decamping to India in 1963. The photo, contemporary with the publication, proved that the kettle remained suspended on the fireplace crane at least until 1969 if not later. Interesting. Armed with this information I turned heel and abruptly proceeded back to square one.

Another kettle similar to the one in Willey House photos. This one was found at the Midway complex in Spring Green. Credit: Steve Sikora

The Midway kettle had its tripod legs filed off. Credit: Steve Sikora

During my long quest, I’d taken note of several similar looking, though not quite identical kettles lingering in Wright environments beyond Taliesin West. The Taliesin garden room fireplace in Spring Green has one. It appears to be older because it flaunts a forged iron handle. I also happened upon one at the Midway Farm complex. The flat-bottomed kettle there was unmarked and had its tripod legs filed off for use on a stovetop. Yet another, I spotted in photos of the Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman House in Manchester, New Hampshire. The Zimmerman fireplace has no crane arm, so the kettle is set on a hob next to the fireplace. Eventually, I came to the understanding that the Willey House kettle, distinctive as it may appear, is hardly a unique form. It is an example of a general typology of iron kettles made over a period of a few centuries. Evidently, the aesthetics of this style of kettle are considered by many, appropriate to accessorize Wright’s fireplaces. The appeal is understandable. Like the fireplaces they inhabit, these kettles seem as old as human history and yet in a way, as so often is the case with primitive objects, appear curiously modern. In particular, the ribs that girdle their round bowls lend them an almost streamlined effect.

I’ll return to the lost kettle in due time. But beset with so many questions, I decided that, to better understand the purpose of a fireplace kettle in a modern hearth, it was worth exploring the theory and practice of woodfire cookery.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains

Part 14: Separated at Birth

Part 15: Trading Drama for Poetry

Part 16: A Red By Any Other Name

Part 17: Roll Down to Levittown

Part 18: Cherokee Red The Rejoinder

Part 19: Nothing Lasts Forever

Part 20: The Struggle

Part 21: Giving What They Had to Give

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 1: The Kettle

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 2: The Crane

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 3: Plagued By Fireplaces

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 4: A Heritage of Cooking Fires

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 5: Benefits of the Fireplace

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 6: Transcendental Flame

Part 22: Calling the Kettle Back—Chapter 7: Repatriation

![[Cohen House Tropical Foliage (Abstract Pattern Study), Eugene Masselink, ca. 1957, graphite, ink, and paint on plywood, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Collection, 1910.223.2.]](https://franklloydwright.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/1910.223.2-2-a-320x240.png)