Willey House Stories Part 19 – Nothing Lasts Forever

Steve Sikora | Apr 17, 2020

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

Time goes by, it takes us all,

Nations crumble and empires fall

And who are we

To think that we would always be

You see, nothing lasts forever

Nothing lasts forever.

Ray Davies, The Kinks from Preservation Act 2 Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

I stood onstage with my family during a preservation awards ceremony, awkwardly clutching a plaque, while the presenter read a paragraph from The Natural House. Partway through his benediction over our restoration project, he unexpectedly emitted a convulsive, insuppressible snort, just as he reached the passage that read, (The Malcolm Willey House) “is well constructed for a life of several centuries…if the shingle roof is renewed in twenty-five years or tile is substituted…” The audience laughed along. Even in the minds of dedicated preservationists, it seemed, all of us, and all that we make, arrive in this world, stamped with an expiration date. Wright’s text ends with, “Perhaps this northern house comes as near to being permanent human shelter as any family of the transitory period is entitled to expect.”

Willey House circa 1937, from Nancy Willey’s photo album. Photo courtesy Willey House Collection.

Other than that, Frank Lloyd Wright didn’t expound much upon the expected lifespan of his buildings, though he sadly outlived a number of them, an achievement neither architect, nor parent should never have to endure. The satisfaction of being honored with a preservation award was simultaneously tamped down with the comical reminder of the ultimate futility of it all. This usually unspoken but inherent contradiction didn’t come as news to me but, damn, couldn’t we just celebrate one night before resigning ourselves to the inevitable? It reminded me of another preservation awards ceremony we attended at around the same time.

In that instance, a group of community preservation activists who banded together to save their historic neighborhood from forced gentrification were given an award for their valorous efforts by a city heritage preservation commission.

The same city, I might add, that had already allowed developers to bulldoze their neighborhood for redevelopment months before issuing said award. The mayor lauded the group’s efforts and as witness to the spectacle, I fell into a deep despondency that remains with me still. Our award presentation wasn’t as grimly ironic as theirs was, but I will never forget the lesson it taught. We mortals are all here, hanging from a frayed thread. Likewise, the makings of mankind, regardless of cost or quality, are little more than temporal clouds of vapor, that manifest for an instant, before the scattering wind rises once again.

To think that a declaration of historic preservation can in some way stop the clock is delusional. A plaque, even if it’s made of brass, does not create a sheltering force field around a threatened property. It is up to committed individuals to remain vigilant and to act on the behalf of our historic properties, as guardians. A method I use at the Willey House, to tell visitors to exercise caution inside, is to say, “we stopped making history.” Of course you can’t, actually. There is an obvious physical record of the past every place one could look. The recorded past on chair legs and table tops informs the story of our house, but going forward, we’d prefer new histories be conveyed verbally, as opposed to physically.

The Imperial Hotel, Tokyo. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. National Archives RG111SC box 592 photo 296203. Photo U.S. Army Signal Corps.

We can neither suspend time nor turn back the calendar, but preserving and interpreting the past, allows us to take visitors on a virtual journey, to lead them to a window in time, through which they can glimpse a previous reality, without exiting the present one. It’s nothing short of a magical opportunity.

Edgar Tafel on Wright, “Yet he always changed everything.” Photo by Steve Sikora.

As I said, Frank Lloyd Wright looked forward rather than back, with dubious concern over the lifespan of his buildings. Sure, there are those stories about the breathless days awaiting word on the fate of the Imperial Hotel after the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923. But hard to say, how much of that was an ego-driven, engineering pride, versus an actual concern for the building’s future. What Wright did lecture and write about a great deal was the Law of Change. He recognized that nothing truly alive could ever remain in stasis. He drove the Fellowship mad with his constant additions and revisions to his plans, as his thinking on a project evolved, to the even through construction.

John Howe took to keeping a second set of plans in an effort to circumvent the resultant chaos. Outside the drafting room, Fellows were not immune to the sweeping physical changes directed by Wright, enacted often without rendered plans, each spring when returning to Spring Green, and every fall at Taliesin West.

Olgivanna Lloyd Wright recounts a perfect example in her book Our House:

One day in our desert camp in Arizona, when we were standing together on an enclosed corridor-terrace connecting our living quarters with the large living room, I said to him, “Don’t you think it would be more beautiful if we did not have this wall separating us from the patio-garden—instead you could build long steps leading down to it? We would feel the patio closer to us then.”

Instantly he called out, “Ted, bring the crowbar and a couple of boys.”

“Wait.” I said, “It’s just lunch time.”

“It won’t hurt us to eat later,” he said, and down came the wall—the wreckage and dust flying into our own living quarters. He then changed another wall, and the room, and the fireplace and the ceiling and the openings.”

He was a most flexible and plastic man. Unaware of time, he lived through sorrows and tragedies, joys or humiliations, remaining ever young, fresh—always poised for the next action. Believing with Heraclitus that there is only one unchangeable law, the Law of Change, he embodied this law. He was forever changing, remaining unchangeable. Opposites met within him in perfect proportion.

When original construction at the Taliesins is examined, it is clear that form making in the present tense was far more important than structural integrity in the future tense. Wright probably assumed he’d be renovating again long before entropy could intercede, and rightly so. The Law of Change practically demanded it. The relocation of a masonry wall was no different to him than moving the stakes of a pup tent. Undoubtedly, Wright would have revised his buildings over and over again. It does not follow however, that it is okay for you and I to change them. He was the master architect modifying his own masterwork, whereas we are merely like the misguided art collector, adding blue to his Rembrandt so it better matches his sofa.

In one of the few letters authored by Malcolm Willey to Frank Lloyd Wright, and his last, on February 22nd, 1957, he warned of the “new superhighway” being planned that “will go through the living room or at least through our front yard,” a shocking revelation, to which, there was a deafening lack of response from Wright. Maybe he didn’t like Malcolm, or maybe he didn’t care.

Portrait of Frank Lloyd Wright.

According to J. Aubrey Banks, a Taliesin apprentice who worked with Wright during his last decade of life, “He didn’t care that his buildings survived, but that the idea of his buildings survived.”

An all too common site in rural regions and all across the American landscape. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. Photo by Carl Wycoff.

His wife felt differently. When Northome, the second Francis Little House that stood on the shore of Lake Minnetonka was to be torn down, fragments of it were acquired by museums; the living room went to the Metropolitan Museum, in New York, the library to The Allentown Art Museum, in Allentown, Pennsylvania and a hallway to the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Olgivanna Lloyd Wright believed her late husband would not have approved of “scattering the parts,” saying it “violated his principle of organic architecture.” She did however believe that the building preserved in its entirety, in context, on its original site for which it was designed would have been commendable. Still, parts are all that remain and we are grateful for them.

In the end, I suppose it does not matter how Wright, himself felt about the fate of his buildings. History is preserved for the understanding of future generations, not for benefit of past generations. A preserved building has no value to the dead, but can be invaluable to the living. I for one, continue to learn as I explore the depth of the one house I have intimate access to.

While habitations in other parts of the world may remain vital for centuries, in America little in the way of the built environment is considered useful beyond 100 years, the approximate maximum limit of a human life. Countless outmoded barns, churches, schoolhouses and town halls of rural America are a sad testament to this. After a period of disuse stemming from perceived or actual obsolescence, follows the cessation of maintenance. Roofs begin to leak, ridges fail and in rapid succession, with broken spines, walls buckle and buildings collapse into themselves, ultimately reduced to twisted piles of hand-hewn lumber. I’ve seen the increased loss of otherwise useful buildings; over the course of my own lifetime and apparently, it is an accepted reality for us Americans, even preservationists among us. Exceptions to this “one century and done” rule are rare.

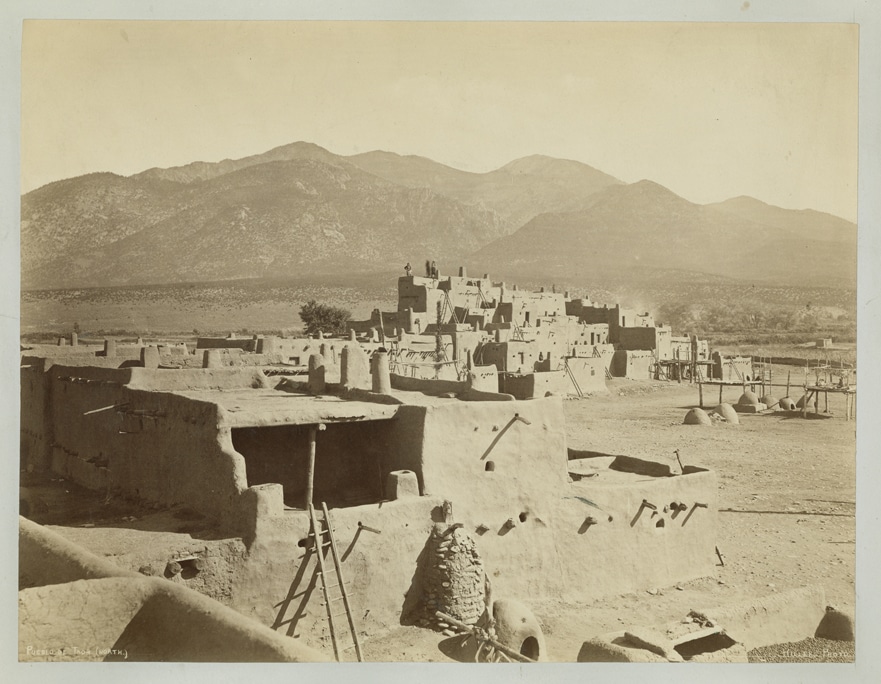

Pueblo de Taos, home of the Tiwa First People, is one of the longest continuously inhabited dwellings in North America, a living environment for over 1,000 years. Visiting the pueblo is like stepping back into time, or rather into timelessness itself. Despite the shocking technological developments since its inception, including the introduction of horses to North America, invention of steel, the advent of electricity, internal combustion, the internet, life pretty much goes on as it always has. Fortunately the fate of this structure has never been in the hands of anyone other than its original inhabitants. It has not been redeveloped into a day spa or boutique hotel. The idea of architecture existing on a different timescale automatically shifts our perceptions of its meaning.

The Taos Pueblo, circa 1973 standing very much as it does today. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. SMU Central University Libraries. January 1, 1873. Hillers, John K., 1843-1925

Long-lived structures exist outside the triviality of trends, styles or movements. When a building lacks the obvious cues that might otherwise date it, we are forced to consider it differently. An ancient building, whose usefulness surpasses countless generations, is imbued with a kind of spirituality. This timeless quality, difficult to date, is a trait that persists in Wright’s architecture. Even his most ephemeral works like the Ocotillo desert camp seemed to have it.

The desert masonry created for Taliesin West, “a beautiful ruin.” Courtesy Wikimedia Commons. Maarten Nijman.

Buildings are fragile, human inventions. To remain vital, a building must first remain useful. It must be valued. Then, it must be loved and cared for. Longevity requires vigilance and a regular maintenance schedule, because buildings are vulnerable to untold forces constantly acting upon them. It is relatively easy to put an end to one, just by ignoring it.

Steve Jobs owned the 1925 Jackling House, a Spanish Colonial Revival home and estate in Woodside, California. After 10 years in residence, the design-obsessive Jobs wanted to tear it down and replace it with something modern.

The Western Region of the National Trust for Historic Preservation repeatedly refused to allow the structure’s demolition. In the biography written by Walter Issacson, it is explained how Jobs defied the commission by abandoning the house and leaving a window open upon his departure, merely cracking the lid on Pandora’s box.

The truth of the story is actually worse. In his wake, Jobs left doors and windows standing wide open, a standing invitation to the elements, flora and fauna and local vandals who ultimately performed the coup de grâce in relatively short order. Steve knew how to get what he wanted and flaunted his blatant rejection of rules. He applied the same shrewd acumen that made Apple a success – his combination of intelligence, willfulness and ruthlessness to solve his personal preservation dilemma. After a few short years the house was uninhabitable and permission granted for demolition of historic property cum public health hazard. A lesson for all preservationists, often it is the less obvious villain who surprises us. While the phantom developer in the night is a blatant threat, he requires complicit agencies to do his harm. The greatest menace to historic buildings, are the property owners themselves who act, ignore, or disfigure all of their own accord.

After we undertook the extensive restoration of the Willey House, we understood all too well its frailties. Its Achilles’ heels were made evident after a mere decade of deferred maintenance and outright neglect. The brick structure surely will stand long into the future even if the bricks themselves spall and mortar joints exposed to weather powder and fail. Wright was correct in calling out the wood framed roof as a potential weakness. When we acquired the house, less than a decade after previous re-roofing, leaks from unaddressed framing problems caused significant headaches resulting from wet insulation, rotted framing and crumbling plaster.

The Willey House masonry going up in the summer of 1934. Courtesy of the Willey House Collection.

Simple roof leaks will ultimately take down any building when ignored. On my first visit to the Willey House in November of 2001, I found it beguiling and tragic depending on how I chose to shift my gaze, water damaged, utilities off, radiators and plumbing broken, deadly cold inside, clearly on its way out of this world. But like a fading peony, on the verge of coming to pieces, its allure was the greater for it.

The Willey House living room, week 1, April 2002. Photo by Steve Sikora.

There is a profound beauty in all things fleeting. In fact, impermanence may be the single most vitalizing aspect of allure. The Japanese recognize the aesthetic value of Wabi-Sabi, nothing lasts, nothing is perfect, nothing is finished. This enlightened and consciously passive worldview embraces transience and imperfection in the physical world. Wabi-Sabi embraces the laws of change. This philosophy was clearly understood by Frank Lloyd Wright and is amply evident in his own delicate work.

Much to the chagrin of generations of dedicated preservation teams, one need look no further than his own homes to see that Wright was more interested in presence than permanence. Each and every Wright home constantly evolved, sometimes through catastrophe sometimes capriciousness. Three distinct, iterations of Taliesin have existed, each characterized by the devastating fires that put an end to their predecessors.

But in truth, an incalculable number existed through a steady state of unconstrained evolution. Even at his Oak Park Home and Studio the structures underwent frequent revisions and additions. According to John Lloyd Wright, “Dad even rearranged the living room furniture on a daily basis.” Wright’s living spaces were treated as laboratories for architectural experimentation. But more than that, change itself was a constant for Wright. He understood its value, embodied and embraced it.

Olgivanna Lloyd Wright was often able to articulate her husband’s ideas in a surprisingly lucid manner.

She shared a story in her book The Roots of Life that helps explain Wright’s peonage to the ephemeral:

Mr. Wright and I had many financial difficulties. I remember when we invited some people for dinner one day, I was very anxious to make everything look beautiful. At Woolworth’s I bought flowers made out of pale gold shells with bright red centers and some iridescent glass bowls. I took a long time to bend the wire stems to extend over the grouping of bowls, interlacing them with candles, setting the table, changing it this way and that, until I finally was satisfied. When Mr. Wright came in and saw the arrangement he was so full of delight, admiration and love that I was positively embarrassed.

“This is real artistry,” he said, laughing with contentment and pleasure at this apparently unimportant circumstance in the scale of things.

A mere harmonious arrangement of a table, or reading something inspiring or humorous to your husband when he is tired or disheartened can be a creative act. Reading a poem can take two minutes in time, but I have known a woman to take two years before reading the two-minute poem. A deep precipice lies between the wish to do and the doing. It is a precipice that not many know how to cross.

The chief idea is to be in love with the work. If you learn to work with joy, you will have learned a great secret that will connect you with a sense of divinity, and in absorption and concentration you will find a hidden force. It is as though you were plugged into a power that is beyond the daily execution of duties, for work of this nature condenses the potential inner force within you intensifying the sense of immortality.

At the 150th Anniversary dinner held at Taliesin West, Lorraine Etchell, a young architecture student who did her undergraduate work in San Francisco, spoke about what brought her to the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. Relatively new to Wright, she observed that he was not a typical modernist, and nailed the distinction in a single word. Wright’s work was “not just modern” she said, his work was “eternal.” Exactly! Modern can only mean ‘of the moment,’ eternal is everlasting.

“Like other good men of genius he was the child of his time, and also, in certain ways, master of the past and the future. The essence of a genius, and all true art, is not superego or of innovation (although he was rich in both); it is that God-given, matrix-based gift and ability to see, sense, and understand more truly and clearly than others do the love, truth, and hope in the wordless immutable laws and rhythm of creation, nature, and humanity; and the gifts and power to forge this matrix with reason, passion, and imagination into incomparable reality.”

– Andrew Devane, from Edgar Tafel, About Wright

Styles, trends and aesthetics are temporal in nature. While ideas and principles have longevity. Frank Lloyd Wright worked in the realm of ideas. He advocated change and never hesitated to act. The Law of Change was part of his creative process. However, those of us dedicated to preserving his creations have no business thinking in the same way. Imagine if you will, the nightmare of an HGTV makeover of the depression-era, Kaufmann country place on Bear Run? It’s unthinkable, right? All that harsh white paint, insipid black and gray wall graphics and glaring pendant fixtures, no thanks. And if not appropriate there, then why should any Wright house be subjected to such personal reinterpretation?

Willey House week 1, with trellis slumping, skylights leaking, glass replaced with plywood, held in place with bricks. Photo by Steve Sikora

Not everyone will agree with me on this, not even in preservation circles. But my belief is that the degree to which you modify your Frank Lloyd Wright home, ultimately, equals the degree to which you have diminished it. If one considers a Wright house as a shell whose contents are subject to continual, arbitrary personalizations and updates, you’ll find it is easy to renovate yourself out of “Wrightness” altogether. This has sadly been proven time and again.

Adaptive reuse is a valuable tool in the greater world of preservation, in circumstance that turn ugly old warehouses into condominiums, abandoned post offices into hotels, or tiny gas stations into coffee shops befitting the neighborhood they inhabit. It is not so useful a tool when it comes to Wright designed structures. The model of preserving the envelope of a building, in order to facilitate a contemporary, interior use, or in the case of a home, to enable modern living patterns, is perfectly acceptable in buildings that are no more than boxes to begin with. But try this with a Wright building and you soon hear the Preservation Jazz Band, slow-walking a coffin through the French Quarter. Both baby and bathwater forever lost, because in Wright’s organic architecture exteriors and interiors comingle. Simply put, they can only be considered interdependently.

Willey House week 1, a trendy but ill-conceived 1970’s bathroom renovation that had to go. Photo by Steve Sikora.

In 2002, thanks to a twenty-year effort on the part of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, the Twentieth Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, granting a global acknowledgement of Wright’s achievements as meaningful contribution to humanity. The year marked the conclusion of a hard-fought struggle for recognition, one that ended in victory and a well-deserved celebration. Just one year later, in 2020, Wright’s perennially struggling school of architecture is on the verge of dissolution.

A spreading global pandemic is throwing a wrench in the works of the American economy. The venerable, non-profit organizations that have long-supported and preserved of our national historic treasures including Wright Public Sites, are on the brink of financial ruin.

And the National Park System, the governmental agency that manages and safeguards our historic sites, is entering year four of a moratorium on recognition of any new National Historic Landmarks. History, like facts, like truth, like common sense, like human decency, we are led to believe no longer matter. In this dismal hour we must rise to the defense of the causes we believe in. Our architecture is our collective memory of self. Our American architect still has much to teach us. Never has it been more critical to act on behalf of the things we hold so dear. Today, change calls again, this time it calls upon us to act, and we must.

Change visited the Willey House in 1954 when Nancy and Malcolm Willey finalized their divorce. She had already left her house, but it never left her. Her family, friends and associates in Sag Harbor, New York all knew of her life adventure and her Frank Lloyd Wright house. I recently learned from Jonathan Foster, architect and first cousin once removed from Nancy, that he and his mother were often regaled with stories about Wright and her house in Minneapolis. Nancy gave him a set of plans for the house, which inspired him to pursue a career in architecture. According to Jonathan “Her connection to the Wright’s cause was so powerful, she continued spending time at Taliesin West long after Wright himself died.” Jonathan said, “I know little about those visits except that I did talk with her once before she went out there…after Olgivanna was gone. I asked her why she was going, and she replied that she liked to be in Wright’s atmosphere.” She went on to say that even with only new people out there, they still spoke the same language. “Just being in Wright’s house, especially, the world he created, was so wonderfully overpowering, that it is energizing.” For those who bother to seek them out, Frank Lloyd Wright’s philosophies and lessons live on vibrantly, instructing us on how to fulfill the promise of a better future. Today that seems like something worth saving at all costs.

Did Nancy feel cheated that she moved on, and left Malcolm with the house? In 1989, Jonathan and his wife had dinner with Nancy in Sag Harbor, to introduce her to their new daughter. As they were leaving the restaurant, Nancy said to him, “It is important to have no regrets.” Perhaps under Wright’s tutelage she too understood the inevitability, and the value of change.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains

Part 14: Separated at Birth

Part 15: Trading Drama for Poetry

Part 16: A Red By Any Other Name

Part 17: Roll Down to Levittown

Part 18: Cherokee Red The Rejoinder