Willey House Stories Part 13 – The Plow that Broke the Plains

Steve Sikora | May 3, 2019

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

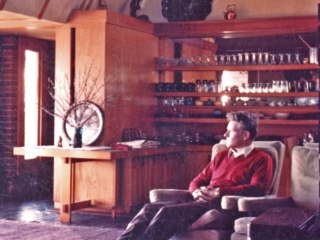

In March 1995, House Beautiful magazine celebrated Nancy Willey in an article entitled “Glorious Times.” The profile swung like a pendulum between two extremes in Nancy’s life story: the early part, building with Frank Lloyd Wright, and her later life spent in preservation of a historic whaling village and environs around Sag Harbor, NY. Nancy Boyd (Willey) was Brooklyn born, but it was in Sag Harbor that her parents owned the summerhouse of her youth. In the article, Nancy recounted a Taliesin gathering where Eugene Masselink told assembled friends, “Nancy’s house was the plow that broke the plains,” “I was so proud,” she recalled. As well she should have been. Her house, after all, was a forerunner in so many ways.

The Willey House was Wright’s only outside commission, after years of personal and professional misfortune. In the lingering shadow of the Depression, it was the first hopeful glimmer of real architectural work to materialize on the drafting tables of the recently founded Taliesin Fellowship.

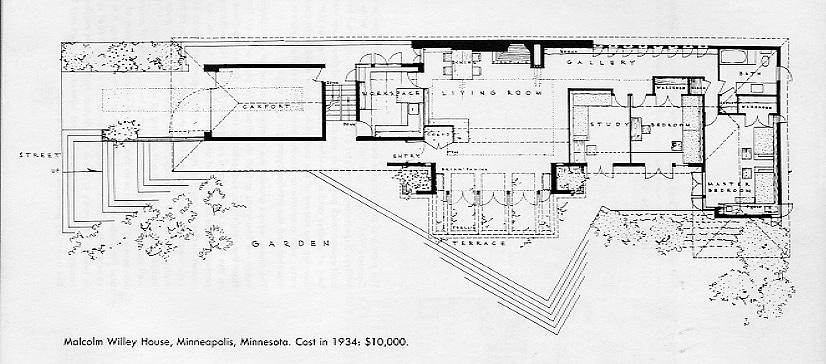

The Willey House in plan form. The Natural House, Frank Lloyd Wright, 1954.

Describing the house as, “the plow that broke the plains” was a sumptuous way of stating that the Willey House broke a long streak of hard luck for the architect. It could also be taken as the house established a precedent – charting a new course for Wright. This small commission set into motion a rising action in his personal history. In concept, it marked the rebound in the dramatic curve of his late career that led to the climax of Wright’s return to relevance on the world stage. Willey represented fresh thinking, a clean slate, and a new way of living for the next generation of clients. In plan, it constituted a pattern for Wright’s Usonian houses to follow, and influenced countless others to pursue his revolutionary ideas. On multiple levels, this unusual, modest Midwestern home broke new, fertile ground.

Nancy Willey and Masselink became comfortable communicating with each other during the planning and construction of the Willey House. A good deal of the correspondence sent from Taliesin to Nancy, was written by Gene. His wit, charm, air of competence, and occasional sarcasm were always in evidence. The pair enjoyed occasional, wordplay in their letters, developing a mutual appreciation that increased over the years, bolstered by Nancy’s visits to the Taliesins. Nancy clearly took Masselink’s comment about her house to be a high compliment. If the curious turn of phrase he used sounds at all familiar, a simple Google search will explain why.

The Plow That Broke The Plains, a film by Pare Lorentz.

A rolling prologue sets the stage for the devastation of the Dust Bowl.

“The Plow That Broke The Plains” was an acclaimed film by Pare Lorentz, released in 1936. The film documents the history of agriculture on the American Great Plains leading up to the resultant Dust Bowl. Controversial in its day, the film was funded with the support of the Department of Agriculture. First time filmmaker, Lorentz struggled to make this movie for years before the Dust Bowl presented the providential gift of government patronage. Prior to that, his efforts were thwarted by the Hollywood studio system, thanks in large part to a book he had co-written, critical of the inner workings of the industry’s Board of Review entitled “Censored: The Private Life of the Movies.” Bucking the studio system created problems for Lorentz, not the least of which was film distribution, at the time largely controlled by the studios.

He was also barred access to existing stock footage. Even with funding secured, Lorentz found himself caught between two powerful forces. Hollywood opposed him; the blessing of government funding became a second strike against Lorentz, because his film was perceived as a tool of propaganda rather than an objective documentary, thus making distribution of the film even more of a challenge. Despite the obstacles, “The Plow That Broke The Plains” was the first commercial, cinematic effort produced with government money, only made possible through New Deal policies because of its timely subject matter. But Lorentz was no political lackey. He was a true artist and environmentalist ahead of his time. His film was produced to a high commercial standard but also possessed a clear vision and message. This was not simply a document of the tragedy of the Dust Bowl, (think the Depression era photos of Dorthea Lange or Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath”). Whereas a glorified newsreel might have sufficed for a government commission, his film instead exposed the root causes of the situation. The subtext of “The Plow That Broke the Plains” was a subversive indictment of intensive modern farming practices begun after World War I.

In dramatic fashion, the film documents the history of American agriculture beginning with the pre-agrarian Great Plains, a healthy, prairie grass ecosystem populated by vast herds of bison. The indigenous prairie grasses were deeply rooted to withstand drought. The buffalo utilized this great resource to the fullest, replenishing its nutrients as the herds freely roamed the breadth of the middle continent. After the buffalo were all but exterminated, the plains became grazing land for cattle ranchers. Soon to follow, the pioneer sodbusters converted grasslands to farmland, but the exposed topsoil on the arid plains became susceptible to the forces of weather and erosion.

Horse-drawn plows gave way to industrial scale farms.

Widespread industrialized farming practices only exacerbated the problem. During the dry Dust Bowl years of roughly 1931-1940, the once resilient grassland ecosystem went powder dry and took to the sky in the form of midnight-black dust storms that swept the plains, quite literally blowing farms off the map. Lorentz teaches a lesson in sustainability, and the value of quality over quantity in the subtext of his film. Over countless millennia pre-agrarian years the first peoples managed to live in harmony with the Great Plains ecosystem. In less than one hundred years time, European prairie settlers jeopardized its very existence. The goals of intensive farming practices were intended to fulfill the dream of American Manifest Destiny, and in post-World War II to serve as breadbasket to the world. In relatively short order, nature interrupted those dreams with a not too subtle reminder that ecosystems have limits that cannot be ignored. The film documented the first time in American history that collapsing an ecosystem was well within the grasp of modern man. Lorentz advocated a kind of return to the garden, as Wright did in his own ways—connecting us to the landscape through living architecture and less commonly recognized, though his own land ethic at Taliesin.

The Taliesin estate has long been home to both architecture and agriculture. Wright’s ancestors on the Lloyd Jones side of the family, cleared and farmed the fields around Taliesin since their arrival in the 1860s. The practice of food production in the Wyoming and Lloyd Jones Valleys had never been on anything other than small, family farms. According to Gary Zimmer, co-founder of Midwestern BioAg, Taliesin Preservation board member and organic farmer on the Taliesin estate, “Farming at Taliesin in the thirties was like most other farms. They plowed, did battle with weeds and didn’t use much if any fertilizer. They had livestock, grazed, and grew mostly small grains and grass hay.” Mary Pohlman who is working on a book chronicling farming at Taliesin confirmed, “Farming at Taliesin during the 1930s would indeed have been chemical free. In part because there was very little chemical farming done in that era on any farm…because of the cost of…even fertilizer, during the Depression years.”

Vintage post card image of the blackened sky over Beaverton, Oklahoma circa 1930s.

Zimmer added that Wright witnessed the horrors of Dust Bowl conditions first-hand, making winter pilgrimages to Arizona. In response, at Taliesin he instituted a practice known as contour farming. Planting crops in contour strips was a method for mitigating soil erosion due to runoff with barriers of deeply rooted crops, when cultivating on hilly terrain. A food crop like corn is planted in narrow, bands alternating with those of a sod-forming crop such as hay, running in parallel bands across a slope. Crop bands follow the contour of the land and circumnavigate hills, like living yarn in a Gods-eye, woven in a cultivated, vegital splendor. Easily mistaken for an aesthetic exercise, strips are laid out horizontal to the slope to minimize erosion by damming runoff, thus protecting the soil from silting away, and thereby maintaining long-term fertility of the land. Zimmer said Taliesin was one of the first farms to use this method.

Pohlman points out the inspiration for this methodology is unclear. Wright “had a strong connection with the University of Wisconsin (especially the landscape architecture programs) who might have brought innovative ideas on contours for erosion control.” One thing is clear, whether inspired by Franz Aust professor of landscape architecture, first hand observations of terrace farming in Asian rice fields by Wright, or the advocacy of the newly formed Soil Conservation Service, Wright’s pioneering farming concepts were recognized as novel if not innovative in 1934. David De Long cites Cornelia Brierly in his book, “Frank Lloyd Wright: Designs for an American Landscape 1922-1932” remembering that professors from the University of Wisconsin brought their students to see Wright’s contour planting. “He laid it all out, it was beautiful.” UW classes did topographical surveys and regularly toured the farmlands at Taliesin to study this new approach. Employing a better way to work the soil was to Wright no different than seeking a better way to build. He may have frequently run afoul of societal norms but Wright always strove to work with nature rather than against it whenever possible.

Farming has always been a way of life at the Taliesin estate. Photo by Pedro E. Guerrero, © 2019 Estate of Pedro E Guerrero

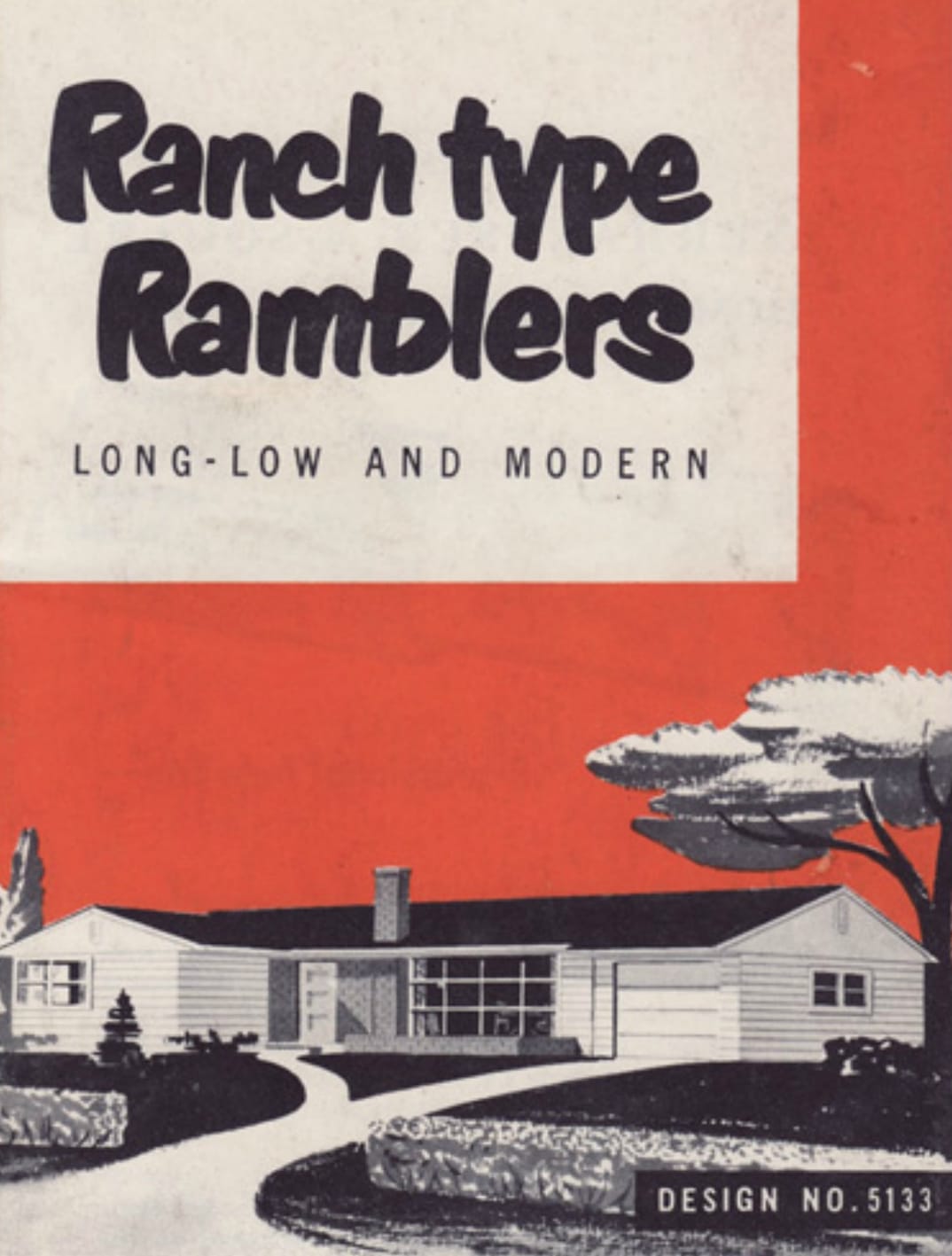

In a curious parallel to the cautionary tale depicted in the Lorentz film, where the efficiencies of industrialized farming spiraled out of control in unanticipated ways, the American ranch house became an unintended consequence of Wright’s 1930s architectural thinking, beginning with the plan for the Willey House and Usonia. Architects, potential homeowners and especially developers, realized that what worked for the Willeys would satisfy the wants and needs of countless others as the nation crawled out from under the weight of the Depression. Daring new ideas that prompted recovery during the 1930s defined the solutions to Post World War II mass housing problems.

This new, low-slung housing typology amplified by the profit motive, spawned tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of illegitimate offspring. In solving specific lifestyle challenges for the Willeys and others of their generation, Wright inadvertently created a new, simplified floor plan easily imitated and suitable for mass production. The trouble was, replicants of the Willey’s dream house were not blessed with the same quality, detail, rich materials use, and least of all, the spiritual sense inherent within Wrightian space. The postwar housing boom became what is called, in retail “the look for less,” in other words, cheaper, false imitations of original things of true value. Wright was aware of what he had inadvertently created and expressed conflicted feelings about it.

The ranch style home came into it’s own during the post-war building boom.

On one hand, in “A Testament,” Wright warned of the perils of conformity, “Unfortunately conformity reaches far and wide into American life: to distort our democracy? This drift toward quantity instead of quality is largely distortion. Conformity is always too convenient? Quality means individuality, is therefore difficult. But unless we go deeper now, quantity at expense of quality will be our national tragedy – the rise of mediocrity into higher places.” The embrace of mass conformity was contrary to everything Wright stood for. Yet, he may have resigned himself to it. Because on the other hand, in an early 1950s address to students at the University of Oklahoma, organized by Bruce Goff, Wright was asked in a post-lecture Q&A “What do you think of the ranch house?” His initial answer was, “Not much. They won’t be around for long.” But followed that with acknowledgement of their lineage, by saying that these were “Frank Lloyd Wright houses.” By the 1950s, I believe Wright reconciled himself to this fact, and ultimately saw fit to create product lines, promoted in House Beautiful magazine, that would help partly address the shortcomings of those would-be “Frank Lloyd Wright houses.” How Wright’s ideas and aesthetics rolled down to the average mass market American will be the topic of a future post.

More than anyone else working at Taliesin, Masselink understood Wright. “Mental telepathist” would have been included on his job description if he had one. Among his many talents, Masselink had an encyclopedic knowledge of cinema. He was put in charge of the Taliesin film program and an impressive program it was. Upon construction of Taliesin Playhouse, the local public was invited to attend. Along with a movie, guests were treated with homemade refreshments for a modest fee that helped offset film rental costs. In his war years’ correspondence, Masselink outlines a Taliesin film program that rivals the later-day catalogues of Netflix or Redbox. A cavalcade of Hollywood features, foreign films, and documentaries were all on the menu at Taliesin. Some favorites were owned and played in repertoire. Masselink was the projectionist as well as the designated procurer of films. He was savvy and opinionated about the movies he screened. It is unlikely a coincidence that he used the phrase accidentally. Whatever nuanced meaning may or may not underlie his words, at the very least he would have been aware of the film by this title. “The plow that broke the plains” was purely poetic figure of speech stating a fact as well as it was a thoughtfully considered compliment from Masselink to his friend, Nancy Willey.

Gus, one of the Willey’s dogs, posed on the terrace in the mid 1930s, the surrounding yard a Portulaca bed inspired by Olgivanna Wright. Photo from Nancy Willey’s photo album

I was curious to know if the Lorentz film had ever been screened at Taliesin. The Willey correspondence is mute on the topic, but Oskar Muñoz, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Assistant Director of Archives & Licensing, pointed me to an answer when he pulled out of his hat a log of films shown at Taliesin, starting with the construction of the Taliesin Playhouse in 1933. There, listed below the date heading 1936, typed in Masselink’s classic, jumbo typewriter font, is the record of a double feature – Charlie Chaplin’s “Modern Times” together with “The Plow That Broke The Plains.” According to the record, it played at Taliesin only once.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words