Restoring the Driftless Hills

Mike Degen | May 15, 2018

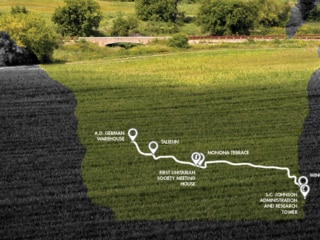

Conservation teams at Taliesin work to re-establish the vegetative footprint and composition of the Welsh Hills as they were in Frank Lloyd Wright’s time.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly.

In his essay, “Why I Love Wisconsin,” Frank Lloyd Wright wrote, “And I come back from the distant, strange and beautiful places that I used to read about when I was a boy, and wonder about; yes, every time I come back here it is with the feeling there is nothing anywhere better than this is. More dramatic elsewhere, perhaps more strange, more thrilling, more grand, too, but nothing that picks you up in its arms and so gently, almost lovingly, cradles you as do these southwestern Wisconsin hills.”

Wright loved this part of the country. There is no other like it. The rolling hills and valleys that define southwestern Wisconsin are here because the glacier wasn’t. This landscape is without drift, the soil and gravel deposits the glaciers left behind. And thus, this un-glaciated place is called the Driftless Area.

Before European settlement fire periodically swept across the landscape. The plant community made up of oaks and hickories, grasses and wildflowers is what ecologists describe as fire dependent; it needs fire to thrive. Without fire invasive species, otherwise intolerant of fire, are able to invade and disrupt the natural balance.

And so is the case in the Welsh Hills, a roughly 100-acre area on the Taliesin estate where Wright loved to spend his time. They serve as a way station for migratory birds and contain remarkable diversity of flora and fauna. But over time the hills and prairies have become overgrown with cedars, honeysuckles, barberry, garlic mustard and more. All were introduced to this area, some intentionally, others not, and have been overwhelming the native plant community ever since.

The Welsh Hills was a favorite place for Wright to spend time with apprentices and friends for leisure and inspiration.

Therein lies the challenge of the Natural Landscapes Program—to turn back the hands of time so the woodlands, oak savannas and prairies can once again thrive.

About 20 years ago local restorationists recognized the remnants of a high quality goat prairie in the Welsh Hills that was overgrown with red cedars, common invaders to these otherwise beautiful, diverse, dry prairie sites. With primitive means, hard work, and financial help through a grant with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the cedars were removed allowing light back onto the prairie. Fire was reintroduced to the landscape, and the restoration of the Welsh Hills was in motion.

Prescribed fire works its way across the prairie. Photos by Ruth Lin.

In 2011 Taliesin implemented the native habitat elements of their Strategic Landscape Plan, bringing a renewed focus to ecological restoration. In determining where priorities should be and being mindful of the limited resources (ecological restoration can be slow and very expensive), attention was directed back to the Welsh Hills.

Work had already been done there, and the Hills have some of the highest quality native communities on the estate. In addition, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Wisconsin Department of Natural resources were interested in re-engaging with Taliesin. They were able to bring badly- needed funding in the form of grants, as well as additional professional expertise and experience to restoring these types of landscapes.

There is an underlying sentiment of pride regarding the beauty of the Welsh Hills among residents of this Valley. “It’s as if they belong to all of us,” has been overhead at times. So in 2012 Taliesin turned to others in the community for support when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service approached the Landscape Program with news that funds for restoration work were available through the Partners in Wildlife Program. Since the grant required a match in funding, Taliesin created a local effort to fulfill the match in funds.

Aerial photographs and other photographic documentation informed staff as to how the Welsh Hills looked in the 1950’s, the last years of Wright’s life at Taliesin. Geographic positioning system (GPS) data was superimposed on current day photographs and taken to the field. With GPS instruments in hand, staff was able to precisely locate and mark the limits of vegetation as they were in the 1950s. That delineation then became the goal for the heavy tree and shrub removal that would re-establish the historic footprint.

“Wright loved this part of the country. There is no other like it. The rolling hills and valleys that define southwestern Wisconsin are here because the glacier wasn’t. This landscape is without drift, the soil and gravel deposits the glaciers left behind. And thus, this un-glaciated place is called the Driftless Area.”

Wildflowers bring the hillside prairies back to life in spring. Photo courtesy of Mike Degen.

Natural resources also came into focus. Wright had planted a grove of pines in his later years that were ready for thinning in order to maintain a healthy stand. A timber harvest was completed and the revenue placed into the Natural Landscape Fund, earmarked specifically for conducting ecological restoration throughout the estate.

Riding on that success came a further evaluation of Taliesin timber resources. The outcome was the discovery of significant value in black walnut trees. Prices were high in 2015, so the sale of the walnut timber returned a good profit. Along with another grant from USFWS for clearing and one from the Department of Natural Resources for prescribed burning, significant progress was finally made.

The painstakingly detailed nature of the work that has been accomplished here over the years is now discernable in these Driftless Hills. Today the relationship of woods and oak savannas to the grasslands of the prairies looks nearly as they did when Wright still lived here.

But Taliesin’s work is not complete. Vigilance will be necessary to revitalize the plant communities of the Welsh Hills. Prescribed fire and the continued removal of invasive species will be the future.

Wright concludes his essay with the thought that “…I must strike root somewhere. Wisconsin is my somewhere. I feel my roots in these hillsides as I know those of the oak that have struck in here beside me. That oak and I understand each other.”

We trust Wright would approve.

Mike Degen is the Natural Landscape Coordinator at Taliesin Preservation. He received his Bachelor of Science degree in Conservation Biology from the University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire, in 1980 and recently completed his 30-year career with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.