Willey House Stories Part 21 – Giving What They Had to Give

Steve Sikora | Sep 1, 2021

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

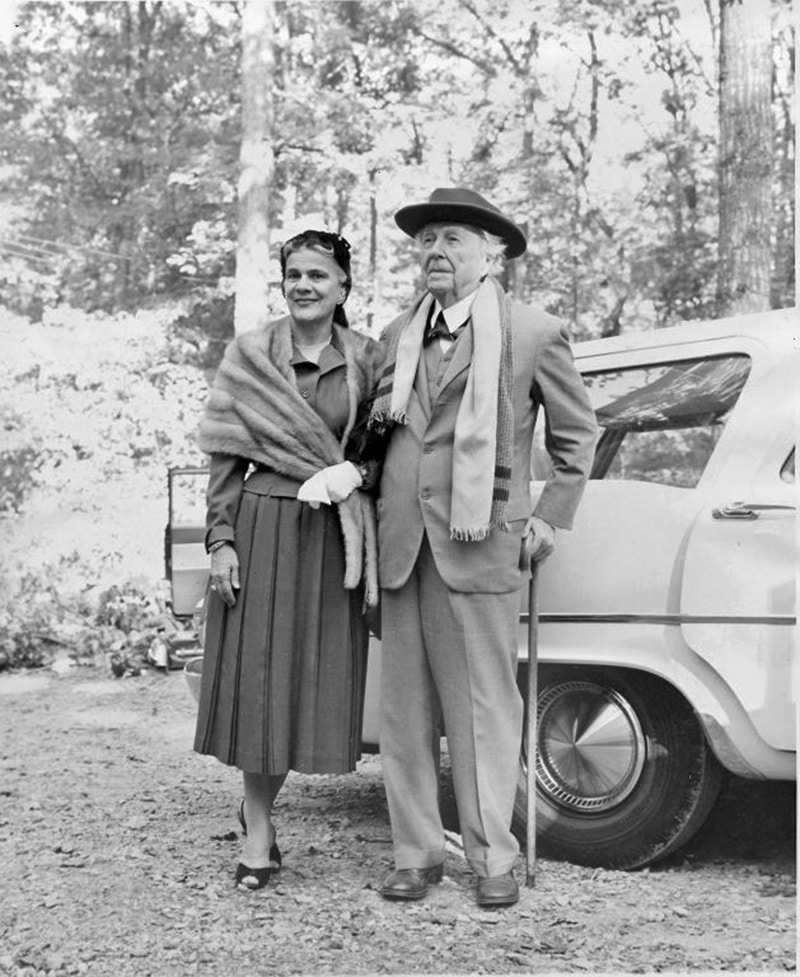

Malcolm and Nancy Willey played midwife to a revolutionary little dwelling born to the world in 1934—the offspring of Frank Lloyd Wright’s midlife crisis. Despite an initial false start and considerable turbulence during construction, they loved the resulting home and maintained long personal relationships with their famous architect and his spouse Olgivanna. Mutual affections persevered for decades beyond the completion of the Willey House, and carried forward even after Nancy left her beloved, tailor-made domicile. The couples wrote and convened with regularity at each other’s homes whenever they could manage it. When they couldn’t call in person, they sent gifts, some as you will see were of lasting value.

Clearly, Mr. and Mrs. Wright’s easy munificence made an indelible impression on Nancy Willey. In her 2001 Oral History interview with Indira Berndtson, Nancy volunteered, “I’d like to emphasize the generosity of giving themselves, giving what they had to give there, so freely and graciously.”

She explained how the Willeys differed in economic status from other, concurrent clients of considerably greater affluence—clients like Herbert Johnson or Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann. She surmised, “People who were wealthy could give back in a wealthy fashion, but we were not. And so I was more aware of how they were in spirit.” Approximate in age, Nancy was fond of Olgivanna. “Mrs. Wright was especially generous with her teachings. She would tell her philosophy, and anything that she felt wise about, anecdotes. I have a slew of anecdotes that are just charming.” The third Mrs. Wright provided Nancy with instruction on topics as diverse as gardening, which Mrs. Willey appreciated, to indoctrination into the study of her Gurdjieffian movements, or “exercises” as Nancy viewed them, to which she was far less inclined. The two maintained an enduring friendship through regular correspondence even after Wright’s death.

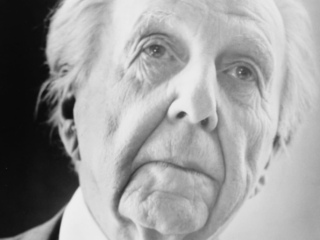

Photographer unknown

That said, warmth and generosity are not typically recognized as hallmarks of Wright’s professional relations. It’s time to add some balance to the record. Little effort is required to plumb the darker aspects of Frank Lloyd Wright at his most peevish, deceptive, selfish and vane. The Wright literature provides a deep wellspring, gushing with unvarnished truths and uncomplimentary episodes drawn from his occasionally sordid life. Sadly, these accounts are easily verified, plentiful and all too satisfying to repeat.

After all, Wright was a supreme egotist, at times a petulant, tyrannical megalomaniac with narcissistic tendencies, who could justify his every personal or societal transgression as an instance of standing his own loosely defined, moral high ground.

In plain fact, he did abandon his wife and family. He did run off to Europe with a former client’s wife. He did abruptly abandon his thriving architectural practice to Van Holst, a Chicago architect barely capable of properly executing the work. And consequently he did leave trusting clients in the lurch. True also, in a most parasitic manner, he thoroughly milked certain dedicated, wealthy acquaintances for all they were worth. He openly defied existing cultural norms in favor of his own evolving personal reality. While were at it let’s not overlook the countless cases of Wright’s chronically overdue bills going perpetually unpaid, in the name of the debt society owed to him, the artist, including those left for his own abandoned family to reconcile.

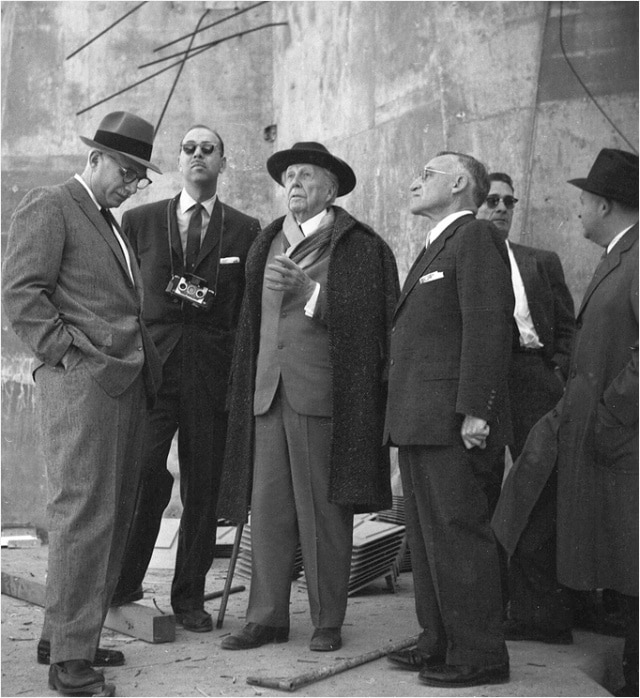

Wright portrayed himself as the perennial outsider from the dawn of his career when he truly was one, up until his glorious sunset, when he struggled mightily to continue playing the part. Like a Rebel Without a Cause, Wright recast himself again and again as the underdog, the misunderstood but righteous genius facing impossible odds. As Edgar Taffel once said: “Every architectural episode in Mr. Wright’s life had to have a villain.” It was only in his struggle against a thing that he was able to bring new ideas into the world. Whether confronting the encroaching plague of the International Style, challenging a skeptical, wealthy client, too accustomed to getting his or her way, or squaring off against the New York Building Commission, in Wright’s cultivated public image as the wronged yet righteous outsider, he could be vituperative, spewing insults as liberally as the houses he claimed to be able to shake out of his sleeve.

Credit: Photographer unknown

Despite its undeniable, prodigiously documented verity, few of Wright’s appalling behaviors ring out in the Willey House Stories. That arrogant, occasionally rancorous, and even repulsive character is not the Wright who is reflected in the writings or recollections of Nancy Willey. Nor does his dark twin reveal itself in the significant body of correspondence between them. Here is a man of obviously imperfect character, a flawed artist, adored in spite of his weaknesses…a man in the midst of refurbishing his largely self-despoiled reputation, and in later life a man now whose generosity outweighs all else. To his new middle class clients Wright became a genius master builder who strove to create for them the most exalted, personalized experience that architecture can provide to humankind. This is the Frank Lloyd Wright seen through the eyes of his adoring young clients from the 1930s forward, a persona far different from the character vilified by his legions of understandable detractors.

No person of note rises to high status in life without desire and a fervent belief in the thing they intend to achieve. The act of remaking a Wisconsin farm boy into the greatest architect of all time was certainly no exception. But when elements in the external world interfered with Wright’s self-definition he retaliated, lashing out at anyone or anything that might tarnish the brightly burnished image he fashioned, by casting a shadow of doubt over it. This is why unsympathetic agencies, callous institutions, fickle patrons, and wrong-headed architects with competing worldviews were so often the target of Wright’s ire. Their actions were invalidating the sacred die he had cast for himself. That was simply impermissible.

Nancy Willey was hardly blind to Wright’s foibles. But they were not what defined the man for her. Nancy’s recollections of Frank Lloyd Wright’s benevolence concur in tone with those of Roland Reisley, an original homeowner who built with Wright in 1951 and again in 1956. You’ll find it is virtually impossible to coax Roland into saying anything negative about Mr. Wright. Not that he should. His experience with the architect reflected Wright’s profound empathy, patience and attentiveness to the needs of his courageous young clients, in this case, Roland and Ronny Reisley. Roland attributes Wright’s congeniality to his own tender age at the time. Without question, Wright saw a hopeful future reflected in the eyes young people, especially if they believed in his ideas, and even more so when they were willing to build with him. I don’t dispute any of it, but I suspect another factor was also at work. Frank Lloyd Wright claimed that he didn’t believe in the myth of the “common man.” Suggesting, he considered no man to be merely “commonplace.” Perhaps that explains why Wright seemed to treat clients who were of moderate means so differently from those with deep pockets. For as haughtily as he thrust his architectural genius and outsized ego upon the world, Wright himself was not high born. In fact, his early life was tragically mundane. Though, from an early age Wright’s design prowess was an incontrovertible fact, his puffery and eminence were largely a projection of his own making. Wright’s origins were remarkably humble, regardless of how romantically overblown they appear in his autobiography. His true inner self is evidenced by his resolute Mid-Western work ethic, his constant need to prove himself, and is particularly demonstrated by the admiration he held for skilled workmen capably applying their craft. Wright loved observing craftsmen applying their trade. He could do it for hours. He appreciated the pride of a job accomplished to the highest professional standard. These things suggest that he never completely lost touch with that impressionable boy who spent summers working the land on his uncle’s farm, learning the hard truths of toiling upon the earth, and earning every blister and ache. Beneath the unbending tutelage of his Lloyd Jones uncles, he first understood the value of hard labor, then, grasped the higher value of perfecting it. Though it may have felt like indentured servitude to some at times, this was how Wright also taught his profound understanding of the benefits of integrity through diligence with the Fellowship.

Believing with all their hearts in the great wizard, the Willeys were fully aware of that inner man standing behind the curtain and embraced him fully. They came to know the Frank Lloyd Wright who dwelt behind the mask of public persona. For their part, the Willeys helped to fortify the myth-making, all while helping Wright secure lectures in the Twin Cities whenever possible just to help keep Taliesin afloat. To incrementally raise much needed cash, they even hawked copies of The Disappearing City to their friends and colleagues. Good friends indeed.

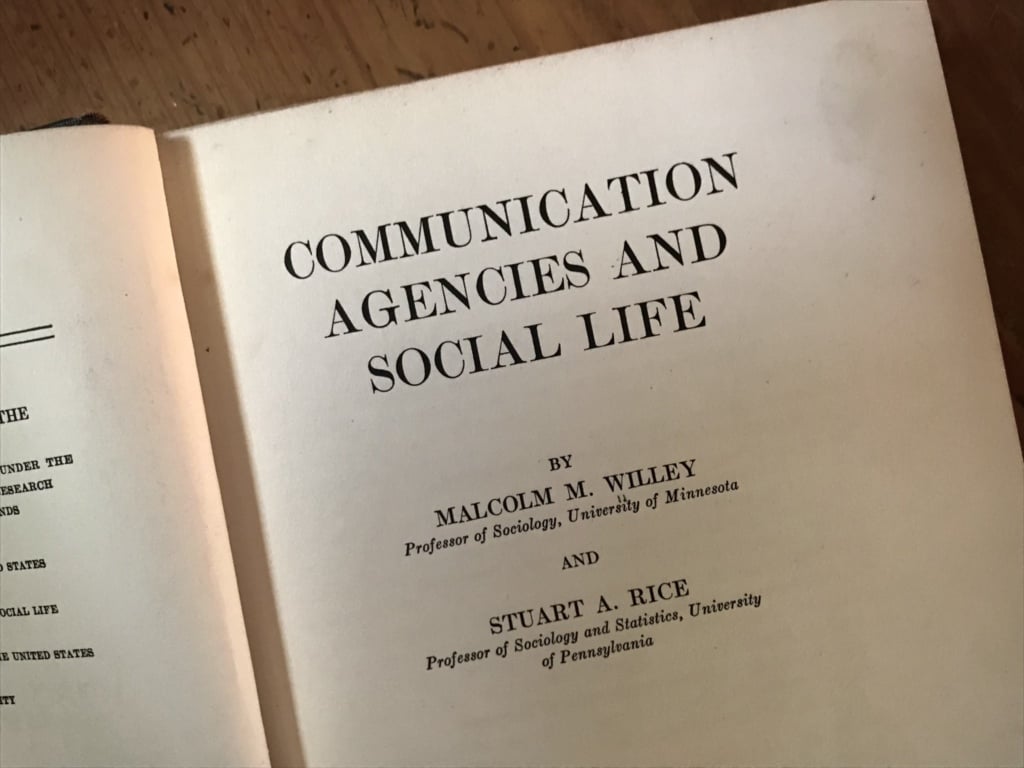

A study published by Malcolm M. Willey and Stuart A. Rice as part of a series of monographs prepared for The President’s Research Committee on Social Trends, established by Herbert Hoover in 1929. Credit: Photo by Steve Sikora

Beyond their incidental fundraising efforts, the Willeys proved useful in other more subtle ways. Malcolm Macdonald Willey a prolific originator of academic thought, churned out a succession of lofty publications: Sleep as an Escape Mechanism, 1924, The Country Newspaper: A Study of Socialization and Newspaper Content, 1926, Readings in Sociology, 1930, The Role of Radio in the New Social Order, 1935, Depression, Recovery and Higher Education, 1937, The Functions of the Newspaper, 1942. He regularly sent Wright copies of his latest hefty volumes even joked about their bulk and weight. “On a poundage basis, in comparing your new book to mine, I win easily. But on any other basis, the laurels are all yours.” And at least one of his academic endeavors, the 1933, Communications Agencies and Social Life, co-authored by Stuart A. Rice is credited with helping to inform Wright’s developing ideas on Broadacre City, an obvious topic of discussion during their many weekends spent at Taliesin. The research study was part of a series of monographs prepared under the direction of The President’s Research Committee on Social Trends, established by Herbert Hoover during the early years of the Great Depression.

In a 1935 missive Gene Masselink thanked Malcolm for sending Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class, which “from Mr. Wright’s hands will pass on through the fellowship to become a valued addition to our small but significant library. Already Veblen’s name has been added to the list of men whom Broadacre City commemorates.” Veblen’s theory rested upon his observations that it was not the activities of the wealthy upper class that created a productive society. Rather, it was the efforts of the working and middle classes that entirely support the economy and underpin the whole of society, a debt owed to none other than the common man.

Understanding the rigors of farm work at Taliesin, Nancy Willey showed her devotion by mailing favorite record albums to the Taliesin Fellowship, music to weed by.

In a letter to Eugene Masselink, Nancy wrote:

August 1, 1940

Dear Mr. Wright,

Yesterday we went shopping for some music for Taliesin. When we heard the music from Dido and Aeneas suite, we could just imagine it flowing out over the countryside from Romeo and Juliet, making the weeding of the onion patch the vigorous and ruthless!

We hope you will enjoy it. We send it too with a special bow to the musicians of Sunday Night. Since you all were taking an interest in Purcell and the music of his period, we hope that this will add to that enjoyment.”

Greetings to you all,

Sincerely.

Nancy and Malcolm

After which a disappointing response came from Gene:

August 14, 1940

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Willey:

Mr. Wright’s pleasure in receiving the records was not marred by two concurrent tragedies:

- Diddo and Aeneas has already been playing a part in the weeding of the onion patch (our interest in Purcell having been on the air for some time).

- And – most unhappily – one record was broken in two.

So – we are sending them back to you hoping that your record company will make up the damage and that perhaps you would happen on more Purcell or music of the period equally conducive to corn picking, which is the order of the day.

Sincerely,

Eugene Masselink

Nancy suggested that she instead send Prokofieff’s Peter and the Wolf.

Gene replied, “sorry the records are causing this trouble but Peter and the Wolf is part of our collection.” Finally he advises, “However you would please Mr. Wright tremendously if you can get a recording (Victor) of the Sonata in A Major for cello and piano (Casals at the cello) by Beethoven.”

Given the difficulty with gifting record albums, Nancy turned to cheese.

June 7, 1943

Now, “Happy Birthday dear architect.” We are sending you for our greetings a “Minnesota Blue” cheese. For “the good provider.” I realize I am sending it into a rival cheese state, but we think our “blue” is pretty good. I’m sorry I was not smart enuf to have it arrive Tuesday. Our farm Campus has stopped handling it, but Saturday I rustled around and “overcame obstacles,” and obtained it elsewhere. We imagine the Fellowship will enjoy helping you enjoy it.

With affectionate good wishes from Malcolm and Nancy

Nancy Willey was an author as well. Her published writings were not weighty academic tomes. Instead, she wrote concise histories related to the heritage and preservation of the seafaring culture of her beloved family summer home in Sag Harbor, New York.

September 28, 1945

I’m sending Olgivanna a copy of my “masterpiece”. She gave me a lovely interest and enthusiasm for my first: Story of Sag Harbor

In a second letter to Wright, Nancy wrote a tongue in cheek defense of her Early American passion:

I love the little old town, and believe there is much fine American tradition there, that is well to honor. What is your comment? The “the prostitute in the back of the room had better sit down?” or is there a better side? I am writing a sort of guidebook, telling the tales of the old houses, and a bit of the human side of the architecture. Gosh I feel like Brutus! If you write me and begin “dear Brutis,” then I’ll know my soul has been lost.

Nancy Willey

In September of 1950, Malcolm had an opportunity to defend Wright, when he was queried by the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards as to Frank Lloyd Wright’s qualifications as an architect.

Dear Sir:

Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright, Architect, Taliesin, Spring Green, Wisconsin has employed the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards to prepare a formal record of his education, experience, and professional standing, to be used in making application for registration in States which have laws regulating the practice of architecture. In the information, which he has filed with this office, Mr. Wright states that he served as architect on the Willey House for you.

Will you please confirm, at the bottom of this letter the applicant’s statement of professional services rendered for you, adding any additional comments you wish to make in regard to his competency, business care and integrity? Any statements made by you will form part of a confidential record to be used only for the information of legally constituted State registration authorities.

Yours very truly,

N. C. A. R. BOARDS

Annette McRoberts

Assistant Secretary

Malcolm responded officiously on university stationary, with a degree of thinly veiled sarcasm, and on September 27, 1950 he shared the gist of it with Wright, and included a copy of another recently published book:

I thought you would be interested, even amused, at the letter I have had from the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards. As you will see from my reply, I answered it with a straight face and very seriously. It really is funny!

“Mr. Wright’s services as an architect were eminently satisfactory and our relationship with him in every way were most happy. —Of his place as an architect, I am sure I do not need to write. Only a year ago he was awarded the medal of the American Institute of Architects, the highest honor that can come to an American Architect. His reputation is international and the long record of his distinguished buildings in the United States obviously places him in the forefront of American architects.”

… Under separate cover I am sending you a copy of a book, which was published only yesterday by our University of Minnesota Press. It is a book by one of my friends and colleagues here on the staff. I think you will enjoy turning the pages, and some of the fellows may wish to look at it with care, especially those who are interested in sculpture.

The January 1938 Architectural Forum in whose pages Wright bestowed the title “Superintendent” upon Nancy Willey.

Credit: Photo by Steve Sikora

Ever the devoted friend, Nancy Willey unabashedly adored her architect. In January of 1938 she reported that while visiting the Mayo Clinic for treatment of a medical condition, her spirits were brightened by having Wright’s likeness in the room. “During the first of the week I wanted to write you and tell you how cheering and splendid a thing your portrait is, when one is away from home, in a hotel room. I have four or five of them around the room and they make me feel I am not so far from home. But since Malcolm brought down the Architectural Forum, last night, the joy of discovering Time is outdone by the glory of the Forum.”

I’m not certain how many portraits would be considered normal. But these clients were more than star-struck admirers, Malcolm and Nancy Willey were intimates of Mr. and Mrs. Wright. They required no secretary or intermediary to gain direct access to the couple. When Indira Berndtson asked Nancy to name her primary contacts at Taliesin, she answered, “When I visit, my main contact was with the Wrights.”

And of course as I said earlier, there were gifts from the Wrights…

In a February 6, 1935 letter to Olgivanna Nancy wrote, “We love the things you sent from Taliesin; they make the house more living. The figures and the gourds; and the wine and the Jelly in their way.” The figures she alluded to were a pair of Native American statuettes cast in glazed ceramic, miniature iterations of what originally were intended to be towering monuments.

An original set of 1929 Charles Morgan Nakoma and Nakomis statuettes, a gift from the Wrights to the Malcolm and Nancy Willey. Credit: Photo by Steve Sikora

Nakoma and Nakomis—A Brief History

In 1923, the Madison Realty Company, developers of the planned suburb of Nakoma, which included a country club and golf course, desired to evoke associations with the Winnebago Indians, a tribe indigenous to the region. Frank Lloyd Wright was engaged to design a dramatic tableau at the site entrance, complete with reflecting pools and two monumental sculptures—the Indian Memorial at the Gateway to Nakoma, as it was to be called. Wright designed a mythical 18-foot tall male figure Nokomis, and a 16-foot tall female figure Nakoma. The conventionalized sculptures were what Wright called ‘”A Study in Harmonious Contrasts. About them he wrote:

Nakomis, rectilinear, dominant above a gleaming plateau; teaching his young son to take the vow to the Sun-God. Nakomis represents the Objective, aggressive, dramatic principle in Nature. From his projecting surface rises a tall jet of water—the supply for both basins.

Nakoma, curvilinear, submissive above receptive basin. Her brimming bowl and children a symbol of Domestic virtue. Into this second basin flows the water from the plateau—a symbol.

The humble figure of Nakoma is set facing her warrior chieftan: the proud figure of Nakomis is set facing Nakoma but slightly to one side in dignified preoccupation with his official rite: his duty to posterity.

—Frank Lloyd Wright

The development, country club and monuments never panned out, but miniature sets of earthenware ceramic statuettes were created in 1929. The edition number is unknown, but one set was given to Malcolm and Nancy Willey. The set gifted to the Willeys was glazed in gloss-black, laced with tiny metallic flecks undulating within the surface. It is rumored there may have been other glaze colors as well and at least one unglazed pair, cast in terra cotta, is known to exist. Nakomis measures 15 5/8-inches high, and Nakoma measures 11 1/4-inches high. The figures were sculpted, cast, glazed and fired by architect/artist Charles L. Morgan, then a quasi-partner, associate of Wright’s who worked out of Chicago. Presumably black was the intended color for the edition based on a 1930 letter from Morgan to Wright in which he offers to create “a few black sets.”

Photo originally used in the Architectural Forum, January 1938. Note the Nakoma statuette on the deck hovering above the gallery corridor.

Photo by Hedrich-Blessing. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society

All early photos of the Willey House show these figures staged in various locations around the house.

After Malcolm and Nancy divorced and she departed her Frank Lloyd Wright house, Nancy wrote to Taliesin to see about getting another set to replace the pair she left behind.

February 22, 1957

Dear Gene,

Have wanted to write you to say how thrilled I was to see your beautiful designs in the House Beautiful number. I’m having a short holiday visiting friends in Florida and, so have a moment to do so.

I often wonder if my Taliesin friends get to New York often in connection with the Museum. I would be so pleased if you would give me a call one of those times, and let me catch upon the news of you all. I have been wishing I could obtain another pair or a single of the Indians – ceramic figures (that Mr. Wright designed) for my little apartment, as I know Malcolm would not want to part with the ones you gave us long ago. I’m going to mention this to Olgivanna when I write but since I want to write her about her book, which I have been reading earnestly, that letter may be delayed!

With all good wishes,

Nancy Willey

It is unlikely Nancy received another figurine much less a pair as they would have been long dispersed.

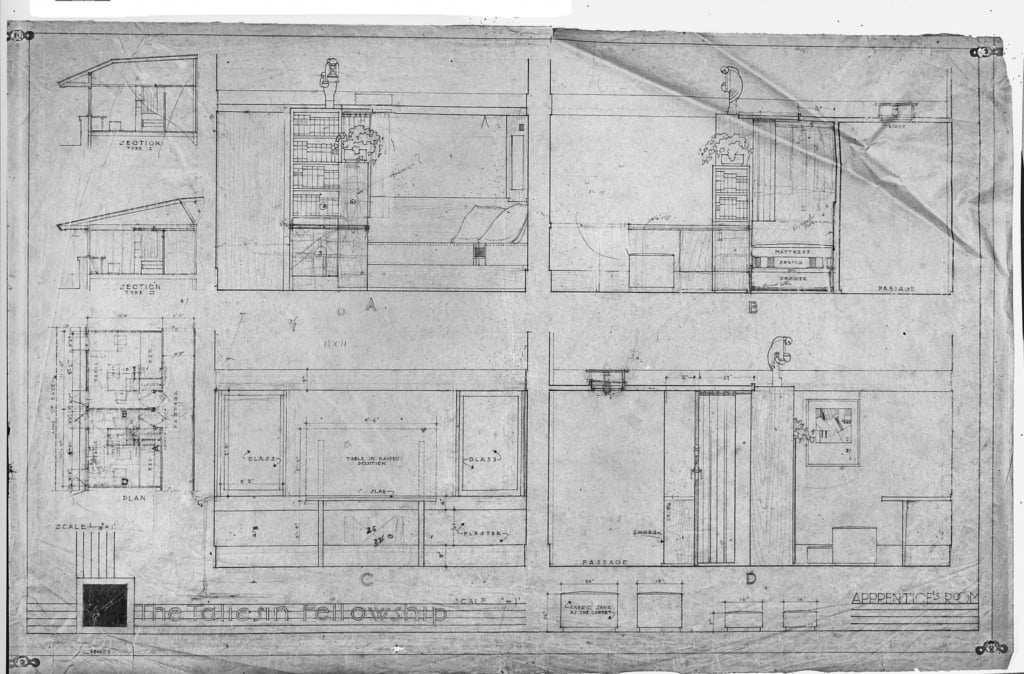

Taliesin Fellowship Complex, 1933

One set of solid black statuettes was displayed in the Taliesin living room, the date and sculptor unknown. That pair now reside in the Frank Lloyd Wright Collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The silhouette of one of these figures appears in a section drawing circa 1933 for the dormitory rooms designed for the Fellowship, flanking the new room at Hillside. Wright presented at least one other black ceramic statuette to clients Paul and Jean Hanna, owners of the Honeycomb House on the Stanford University campus. They were recipients of a Nakomis figure. It was sold recently at auction.

Bronze edition, circa 1974

Photo by Steve Sikora

Coors edition, circa 2011

Photo by Steve Sikora

2018 Pacific Trading edition, circa 2018

Photo by Steve Sikora

The Charles Morgan originals gifted to the Willeys were made of fired earthenware. Nakomis stands 15 5/8-inches high. Nakoma is 11 1/4-inches high.

While the intended monuments in Madison were never realized, iterations of Nakoma and Nakomis figures abound, fashioned in an array of mediums, scale relationships and sizes. Since there is no comprehensive list of these figures I’ll share details on the known examples:

- A plaster set, circa 1929, was sold at auction at Treadway Toomey Gallery in 2013. (Nakomis 16-inches high, Nakoma 12-inches high)

- Christies Auction house sold a set of raw terra cotta figures, circa 1929, in 2002 (Nakomis 18-inches high, Nakoma 12 ¼-inches high)

- A small edition of glazed terra cotta statues were created in 1929. (Nakomis 15 5/8-inches high, Nakoma 11 1/4-inches high)

- A larger, limited edition of 200 sets cast in bronze in higher fidelity of detail was licensed by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. It was released in 1974 to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the design. The bronze edition was sculpted by Willis W. Hubbard. The Foundation stated size of Nakomis is 18 inches high (17 ¼ actual). The Foundation stated size of Nakoma is 12 ¼ inches high (11 5/8 actual).

- Circa 1955-56, a Taliesin apprentice interested in sculpture, Prince Giovanni Del Drago, reproduced the pair under Wright’s guidance. He cast them in concrete and gilded them. 44-inch Nakoma and 36-inch Nakomis these reside at Hillside Taliesin, Spring Green.

- In 1976 the S. C. Johnson Company commissioned the first full-scale replicas of the monumental sculptures Wright designed for Nakoma. Nakomis and Nakoma respectively stood 18 and 12-feet tall. They were executed in Cold Spring granite, mined in Minnesota and carved by two Italian sculptors Flaviano Cenderelli and Bruno Borgioli of Kotecki Monuments of Ohio.

- In 2001 Taliesin Associated Architects revived Wright’s plan for the 1923 Nakoma clubhouse in the form of the Nakoma Golf Resort in Clio, California. To compliment the clubhouse a new set of Nakoma and Nakomis monumental sculptures were recreated, this time at 90% scale and cast in concrete and painted gold, ala Prince Giovanni Del Drago. Nakoma measures 16-feet in height, Nakomis is 11 ½-feet.

- In 2004 the Nichols Brothers released an outdoor edition authenticated by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, 36 and 24-inch set and a 54 and 36-inch set cast in reconstituted stone.

- In 2011 a new ceramic edition of Nakoma and Nakomis figures, glazed in slate grey, were released by H. F. Coors, also licensed by the Foundation. At 15 1/4 and 10 3/8-inches this set is both similar in size and character to the original cast ceramic set, given as a gift to Malcolm and Nancy Willey.

- Yet another edition issued by Pacific Trading is made of cold cast resin and painted gold is currently available. The Foundation stated size of Nakomis is 18 inches (17 3/8 actual). (The Foundation stated size of Nakoma is 12 inches (11 3/4-inches actual).

Nakoma statuette size and detail comparison between editions. From left: Original Charles Morgan edition, 1929, H. F. Coors edition, 2011, Willis W. Hubbard bronze edition, 1974.

Photo by Steve Sikora

Many thanks to Doug Stein for his collected body of research on the history of these figures.

As faithful clients and supportive friends, the Willeys hosted visits from numerous potential clients, for example the Lusks of South Dakota and the Blackbourns, winners of Life Magazine dream house from Minneapolis. And of course, like other Wright clients they received a succession of visitors of all stripes sent by Taliesin—including numerous surprise overnights by members of the Fellowship.

Among the myriad of reciprocal gifts were furniture designs. Sketches trailed in for several years after the house was completed and included a drawing delineating a streamlined beverage cart that would be perfectly at home in Herbert Johnson’s private office or in the Fallingwater living room, both sites having strong characteristics of streamlining. Only a flip up serving extension shaped like the recessed light screen in the skylights gives it away as an amenity designated for the Willey House. There is no indication in the preserved correspondence that the Willeys were paying for these later furnishings.

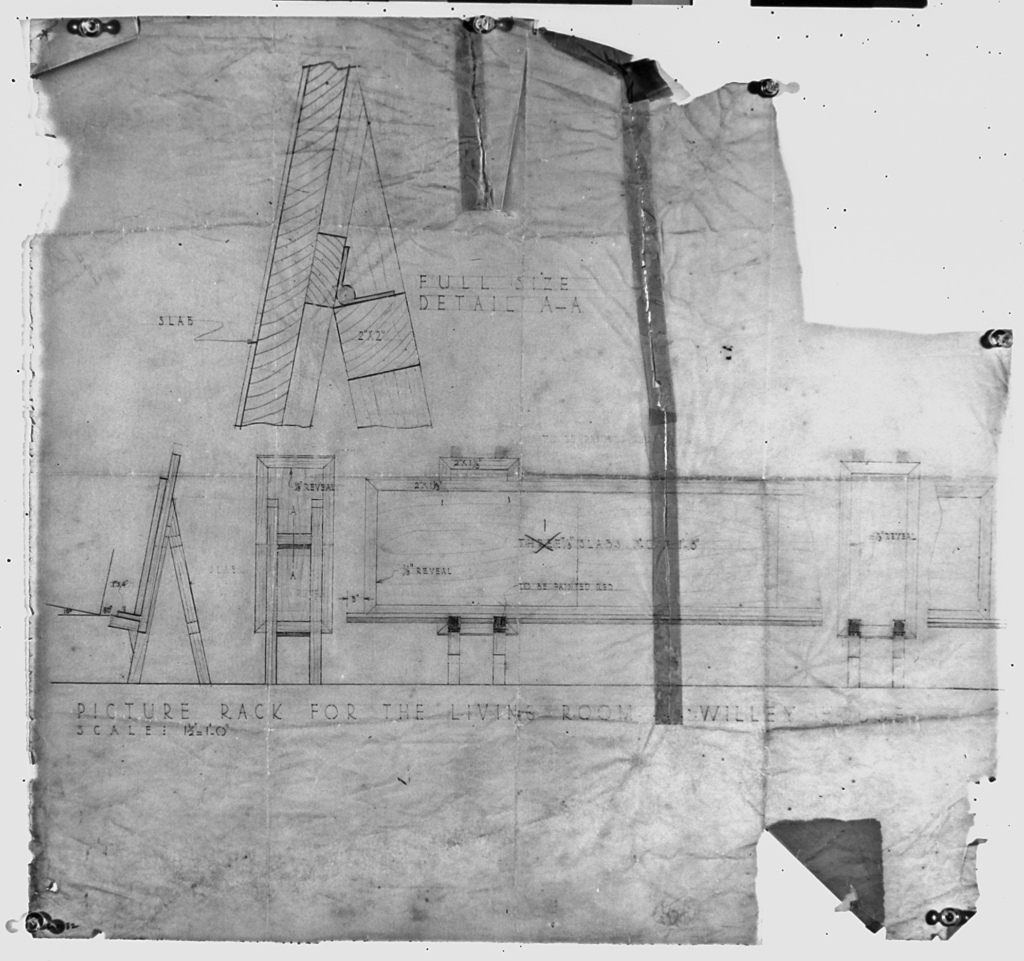

One of the proposed appointments for the Willey House was a massive picture rack that would have dominated the living room. It was a curious addition to the space considering the Willeys neither collected nor owned any art to display upon it. Or so it seemed.

The streamlined beverage cart designed for the Willey House with extendable top, in red tidewater cypress. Built by Stafford Norris from original plans.

Photo by Steve Sikora

Photo by Craig Jacobson

Photo by Matt Schmidt

Japanese Block Prints

From the dramatically sloping ceiling, to the thin cypress trim boards, to the kite-shaped windows, there is more than a passing resemblance between the Willey House living room and Wright’s drafting studio at Taliesin where it was drawn. One correlation that has gone unrecognized is the striking similarity between the sloped cypress panels below the studio windows and along the adjacent wall, designed to display a series of Wright’s Japanese block prints in side-by-side fashion. It so happens that Wright drew up a similar, massive 9-foot long display easel for the east wall of the Willey House living room.

In a letter to Gene Masselink: September 28, 1934:

The picture rack is lovely but it seems extremely large. Shall I have room in the living room for a nine-foot rack?

Sep 29 Gene immediately responded with:

The picture rack is meant to hold several pictures at one time—and Japanese prints, etc—to compare and study them (even if I am a painter).

Credit: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York

Photo by Steve Sikora

Gene and Nancy had a running joke concerning his stature as an artist. She recounted in her oral history, “Oh, yes, we had fun over that, as the letters indicate. You know, I have an index of those letters, and can go exactly to the point where we were kidding each other. I thought: to need a great, great big portfolio—not a portfolio but an easel for art—in my little house: out of place. So I got them to cut it down to about a third of the design. Mr. Wright’s idea was that you compared one thing to another and changed it constantly, but it was too big. Then at one point I said, “Even if you are an artist, that’s too big an easel.” So at some point he returned the remark, “Even if I am an artist” —interchange between us, which I enjoyed, and that gave me the feeling that he enjoyed it also.” As we know today, Eugene Masselink was indeed a gifted artist, a painter as well as graphic designer.

Nancy’s objection to the jumbo easel seemed understandable, since she apparently didn’t own any Japanese block prints, nor did she have the means to acquire any. The print stand was reduced from the original 9-foot width to a more reasonable 36” wide x 41 ¾” high x 19” deep configuration. The change was accomplished by foreshortening the display panel, then reducing the number of leg supports from four to two and widening the distance between them.

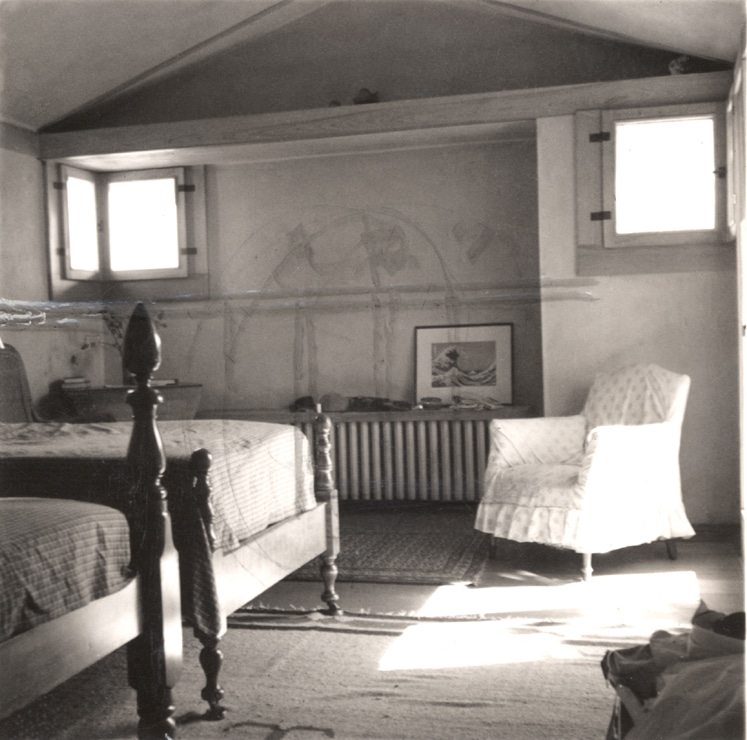

The Great Wave off Kanagawa, by Katsushika Hokusai (Published between 1829-1833). Also known as The Great Wave or The Wave. This print is the first image in Hokusai’s series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fugi. It is his most famous work and one of the most iconic works of Japanese art in the world. Malcolm and Nancy Willey owned a copy of this print

Credit: Public Domain Wikimedia Commons

The question of why the generally art-less and more specifically, print-less Willeys were given a display easel remained puzzling until recently. While revisiting some of the photos in Nancy Willey’s personal album I came across a snapshot credited to a photographer named McQuilken. Although I was familiar with the picture, looking more closely I was amazed to see what was obviously a Japanese woodblock print in the master bedroom. The image was unmistakably a print because it happened to be the most iconic woodblock impression of all time, The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai. It was the first print in his series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, published between 1829 and 1833. The framed image leans against the wall balanced on top of the simplified cypress radiator cover originally made for the room. The photo also shows signs of hand drawn lines depicting the then un-built shelf above the radiator.

Credit: McQuilkin from Nancy Willey’s photo album

Credit: McQuilkin from Nancy Willey’s photo album

A subsequent review of other snapshots in the series presented a further revelation—a second woodblock print hung in a peculiar manner. This one was mounted high in a corner of the living room is possibly a Hiroshige, based on the border treatment, but is of yet unidentified.

These startling, recent discoveries suggest that Frank Lloyd Wright’s largesse toward Malcolm and Nancy extended further than previously understood from preserved historical accounts. It is unlikely that these prints came to exist in the Willey House by any means other than as gifts from Wright. Though one can only speculate. Where they came from and where they disappeared to after the Willeys departed remain a mystery.

While objects like prints, ceramics and red signature tiles became cherished mementos for the fortunate clients who received them, they are ancillary to the real treasure inherent in a Frank Lloyd Wright commission. The greatest gift he granted to every homeowner though less tangible in a physical sense, is certainly no less real. For the most part, like the Willeys, those who became clients found that the act of building with him was a highlight of their lives. Their contact with his larger than life character, no matter how fleeting, became the stuff of family lore. Even the children remember his visits vividly. Direct experience with the man marked a profound and irreplaceable milestone in their personal histories. Furthermore, Wright’s persona became synonymous with the experience of living in their homes. These young families found that his greatest offering was the distinct, personalized character imbued in their homes. The essence of which is expressed in the actual physical form, embedded in the studs, rafters and masonry and resonant within the voids. The invigorated spaces he sculpted for his clients came alive once inhabited. The space he shaped within the walls of their homes was invested with an energy that constantly renewed itself and continues to regenerate through simple human interaction. This is a remarkable trait for any building to possess. Their Wright houses invoked the fourth dimension, marked with a lifetime of moments of constant discovery and delight. Using a range of clever techniques the houses bridged a connection to the immediate landscape and were clearly crafted to the specific needs of his clients out of unconditional love. This kind of enigmatic synergy between spirit and domain simply did not exist inside any conventional box and his clients knew it.

In the second half of his life, Frank Lloyd Wright seemed to embody a heightened capacity for love and affection for his fellow man. A fascinating account of Wright’s kind-heartedness is the case of Lee Ackerman, a man whose aspirations far exceeded his means. Ackerman approached Wright in spring of 1952, with the request that he design a trailer park to be developed in Paradise Valley. Why Wright would have entertained his proposition is hard to wrap one’s head around. A couple deal breaking issues immediately spring to mind: one is that at the height of Wright’s illustrious career, the man in question apparently came to Taliesin empty-handed with no financial backing, yet was not turned away.

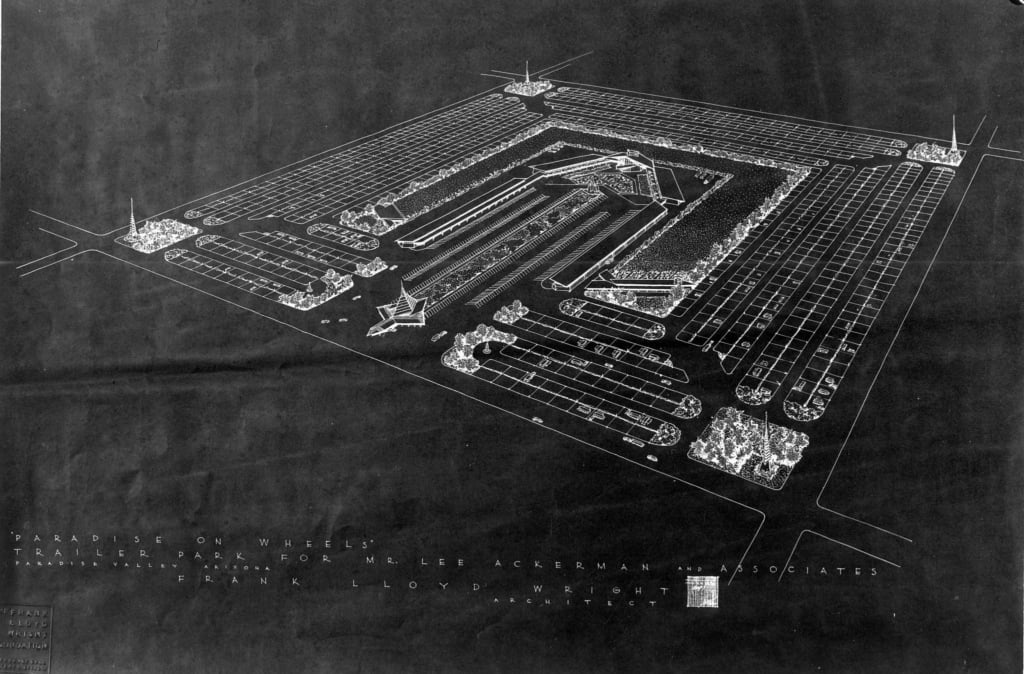

Perspective rendering of the Paradise on Wheels trailer park for Lee Ackerman and Associates, project slated for Paradise Valley, Arizona. Note the flexible orientation of the trailers on their small lots.

Credit: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

The second and more obvious conundrum is that a trailer park would seem to fly in the face of the principles of Wright’s organic architecture. Whether out of empathy or compassion, we’ll never know, Wright asked the man if he could come up with any money, even $400. Mr. Ackerman said he could scrape together the $400, which he eventually did and Frank Lloyd Wright proceeded to design him a trailer park.

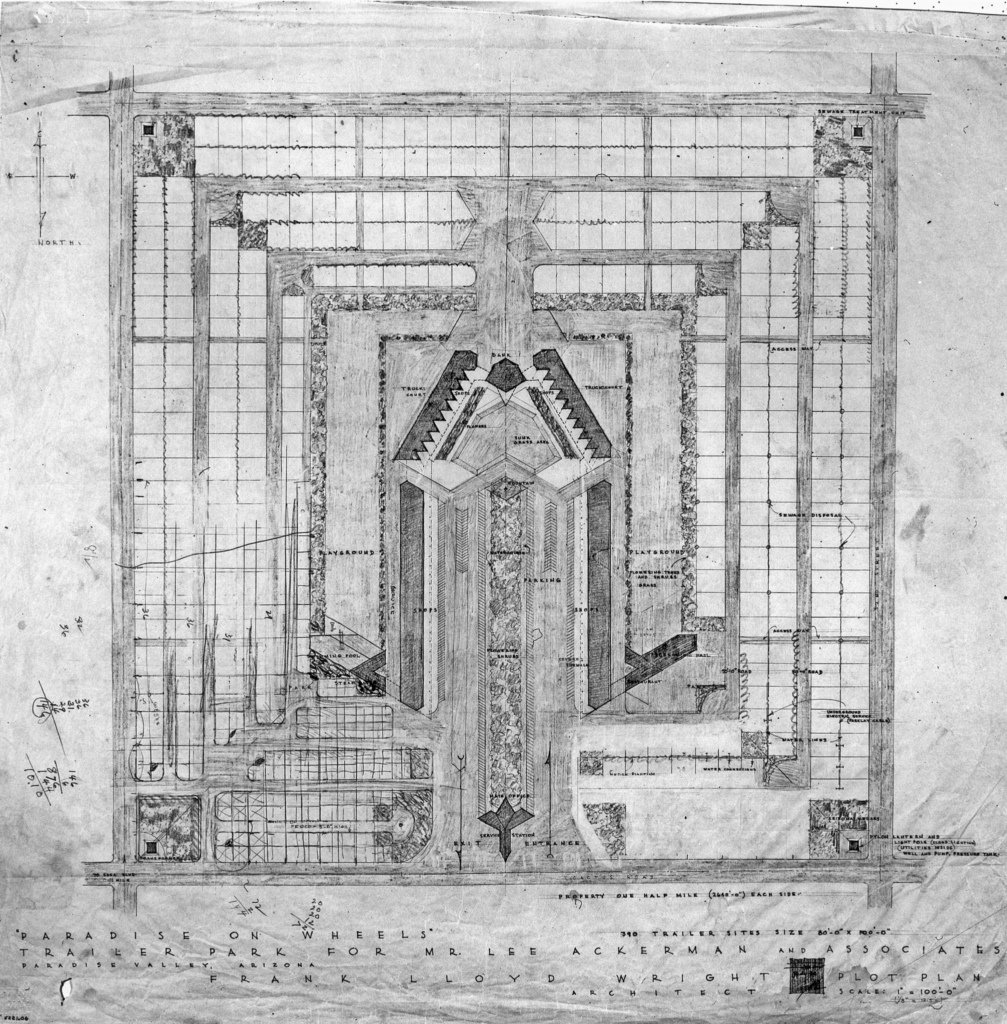

The complex Wright delineated, dubbed “Paradise on Wheels” was a thoughtful reimagining of the typical mobile home community—in other words an unbroken horizon of single wides arranged in regimented formation. While unit density was relatively high by Usonian standards in Wright’s remaking, individual lots were big enough so that mobile homes could be set to alternate in orientation, creating a modest degree of privacy and variety while also carving out space for a small yard. The site plan resembled a board game with an abstract floral form blossoming at its center. The site featured an expansive community complex shared by all the inhabitants of the park. Amenities included a bank, shops, restaurant, recreational hall, service station, swimming pool, steam room, playgrounds, public gardens, a fountain and watercourse. The whole of the colony was surrounded by ample green space for members to interact with nature. Sadly, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives at the Avery do not include any sketches of Wright-transfigured trailer homes but perhaps some day William Allin Storrer will discover one.

Plan of the expansive Paradise on Wheels trailer park. Wright created an environment, offering inhabitants forward-looking amenities such as retail shops, a service station, playgrounds and a pool surrounded by naturalized green space. Credit: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Though a village of mobile homes would seem like the last thing on earth architect Frank Lloyd Wright would wish to attach is name to, he did exactly that. And he put forth his best efforts given the obvious constraints. Wright didn’t do it for the money, and certainly not for glory. Instead, he accepted the commission out of an abiding respect for the human condition. In some small way this project presents us with a complimentary answer to what Wright long called “the small house problem.” His decision to take on something so unintended is reminiscent of the moment Nancy Willey, out of frustration, rejected her unaffordable first scheme and said “I want an eight to ten thousand dollar house for eight to ten thousand dollars. Can I have that?” Nudged on by her helpful encouragement, Wright complied with a house that not only suited her particular needs but changed everything.

Empathy is a prerequisite to good design. In moments like these, the great Frank Lloyd Wright demonstrated his capacity for not simply understanding his clients needs but “feeling” them. He demonstrated his talent to fully grasp the conditions of their lives and his uncanny ability to respond to them with innovative solutions. These unobligated acts of generosity are evidence of his acceptance that all mankind could never afford one of his splendid custom homes, however a great number of people could still benefit from his theories and site planning in order to facilitate a reunion with nature. In Wright’s residential work he sought to quell an unspoken desire embedded deep in our genetic code. This universal yearning is perfectly expressed by the Welsh word “hiraeth.” It roughly translates to a wistful longing for a lost home. Wright understood this deep-seated human need and did his best to satisfy it. By placing a hearth at the center of everything and integrating his sheltered living spaces with the surrounding environment, Wright beat for us a footpath, back to the garden only our ancestors knew.

“Then let the rediscovery of Architecture as Man and Man as Architecture illumine the edifice in every feature and shine forth as the countenance of truth. The freedom of his art will thus find consecration in the soul of man.”

– Frank Lloyd Wright, A Testament

I was pondering how to conclude this meandering chapter in the Willey House Stories when I became involved in a Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy sponsored event called

Originally conceived as a series of Wright-related tours revolving around a specific point on the map, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic was this year reimagined. The norm of gathering to ride in packed busses to tour small houses was tipped on its ear by the health crisis. In the name of public safety the event was virtualized. What seemed like a painful constraint at first and risked only promising further exhausting hours in front of a computer for an already Zoom-fatigued audience, instead presented us an entirely new aspect of touring. Obviously nothing can replace the visceral experience of being inside of a Wright house, least of all shaky, hand held, amateur video. But what became obvious was that the highlight of these owner-led home tours was not a polished examination of beautiful buildings, well-lit and lusciously captured on video, but instead the recounting of the true-life experiences of the homeowners both original and recent in the form of an ethnography—a reminder that buildings are after all about their inhabitants and that the health and vitality of the human spirit is a goal of any Wright design.

“The longer I live the more beautiful life becomes.”

― Frank Lloyd Wright

From the first, Wright’s endeavor was never a mere architectural practice. Like a force of nature he wielded a sublime love only great artists are able to channel and infuse into their work. So that in each and every era of his working life his spaces consistently managed to transcend all previously conceived housing models. Instead of the conventional client/practitioner relationship, he and his devoted client-followers joined in communion. In a ritual form, together they constructed these extraordinary sacred spaces in which to dwell, to ignite their spirits and raise healthy families—extraordinary spaces to be born and die in and to be passed on to future generations seeking something other than a mundane life. Talk about generosity, what greater gift could anyone have ever given us?

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains

Part 14: Separated at Birth

Part 15: Trading Drama for Poetry

Part 16: A Red By Any Other Name

Part 17: Roll Down to Levittown

Part 18: Cherokee Red The Rejoinder

Part 19: Nothing Lasts Forever

Part 20: The Struggle