Willey House Stories Part 18 – Cherokee Red The Rejoinder

Steve Sikora | Feb 21, 2020

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

The tangled roots of Cherokee Red run deep. The mapping of this snarled tracery began with Willey House Stories Part 11 – The Origins of Cherokee Red, prompted by a string of missives between Nancy Willey and Taliesin. After the essay was posted, and abundant new information uncovered, I followed up with Willey House Stories Part 16 – A Red By Any Other Name. But the story refused to rest there. So I have now accumulated a sufficient ball of root fiber to tie a bow around the subject, twice, as I convey the third and final part to this peculiar history. Still, I urge you to read the first two pieces before you delve into this one. Here is a brief synopsis of what you’ll find.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s first reference to the color named Cherokee Red appears in a letter to Nancy Willey regarding Wright’s preference for the solid, background field in a rug plan, proposed to her. As Nancy discovered when she met with a representative of the Klearflax Linen Looms Company, in Duluth, Minnesota; Cherokee Red was not a commercially recognized shade. But, as she so aptly stated in her followup to Wright, “But soon will be!” She was right. Wild fables, inspired by the color’s romantic name, abound, as to its origins and significance. Eugene Masselink called it “an Indian red,” and told Nancy that it was a hue Wright took note of on a trip to the coast. As a color reference for Klearflax Linen Looms, Gene sent her the name of an automotive paint color, found only in the 1935 Olds Motor Works, Duco paint chart, Cherokee Red. This was, it seemed, the original reference, plain as day. But from other corners, long-held myths, swirled around the idea that the color was inspired by, or literally drawn from a piece of Native American pottery Wright had sent here or there.

I investigated that possibility too, and eventually realized that the range of iron oxide reds, we now call “Cherokee” are among the most common pigments on earth. They were used everywhere, on everything, down to the pigmentation, swabbed across the side of a barn in the Valley of the God Almighty Joneses.

Then I found that Betty Cass, a Madison social columnist and friend of the Wrights, on good authority, reported in the Wisconsin State Journal, that the color first drew attention to itself on the Wright’s own breakfast table, in the form of a red glazed cream pitcher, manufactured by Catalina Island Pottery, an unexpected source of inspiration, even if the color skewed a bit orange. These revelations were so exciting I could barely contain myself.

Toyon Red glazes on Catalina Island Pottery saucers. Photo by Steve Sikora

After publication of my second conclusion, came further dribs and drabs of new, vital, and delectable morsels of backstory. Eventually, they could no longer be ignored. In support of the news account regarding the Catalina Island Pottery glaze color, officially known as Toyon Red, it was pointed out to me that Wright was personally acquainted with William Wrigley Jr., the famed “Chewing Gum King.” Wrigley acquired the Wright ghost-designed, Arizona Biltmore Hotel in 1930, just a year after it was constructed, and built a home of his own on adjacent property. Wrigley already owned nearly all of Catalina Island, purchased in 1919. His Biltmore Estate mansion was conceived as a comfortable layover during the grueling commutes between his native Chicago and Catalina Island, southwest of Los Angeles. It is quite possible, Wright may have been a guest at the island (“on the coast”) at some point, and if not, the Arizona Biltmore happened to be a sales outlet for Catalina Island Pottery, a company that Wrigley Jr. also owned.

Wright’s own first foray into the Arizona desert came in 1928, in the form of a four month stay, spent consulting on the Arizona Biltmore. It was then he met Dr. A.J. Chandler, who asked him to design the ill-fated, San Marcos in the Desert resort. To facilitate the work, in 1929, Wright established the ephemeral Ocatilla Camp on the hotel site, as a base of operations, but the resort along with the grand plans of the two men, were laid low by the onset of the Great Depression. Wright’s Arizona snowbird winters commenced in earnest in January of 1935 when Wright and his students were invited guests at Dr. Chandler’s La Hacienda, a former polo stable, now converted to guestrooms. This was the first season that the Taliesin Fellowship travelled en masse to Arizona, on this occasion, to work on the Broadacre City model, funded by Edgar Kaufmann. Every winter spent in Arizona was a souvenir hunting expedition for Wright, with ample opportunities to pick up a few pieces of table service. From Wrigley’s acquisition on, Catalina Pottery was available for sale at the Arizona Biltmore, a place known to be frequented by the Wrights.

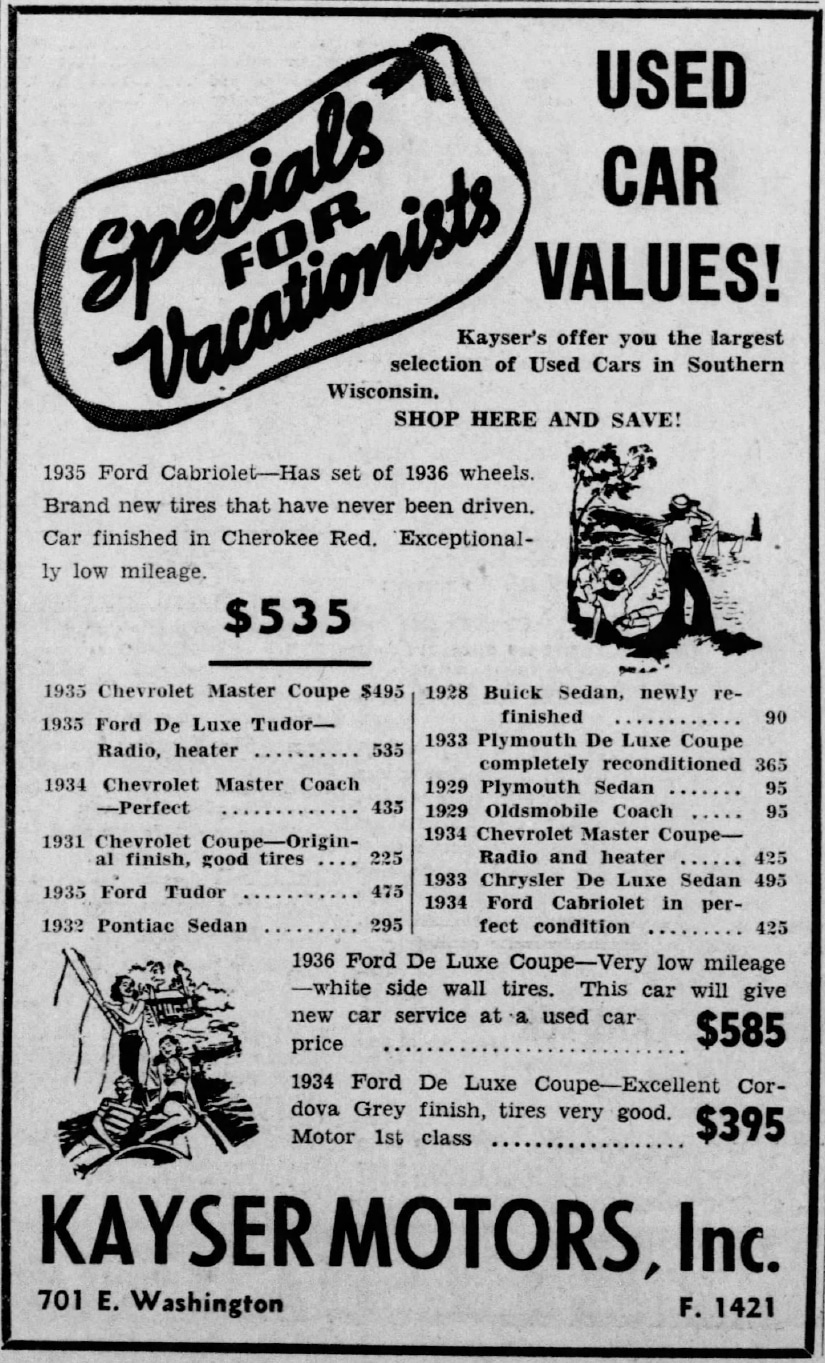

Classified ad for one of Wright’s 1935 Cherokee Red Fords for sale in Madison, in 1936. Via Newspapers.com

Much of the history of Cherokee Red revolves around Taliesin’s fleet of cars. Richie Herink, calculated in his book on the subject, that throughout the years, there were 85 automobiles in total, including the pair of 1935 Fords that were the subject of that Betty Cass gossip column, custom-painted by the Ford factory in some form of Cherokee Red, maybe or maybe not a hue matching the Catalina Island Pottery, based on Cass’ delicious description of it as a “brick-reddish-burnt-orange.”

Two additional pieces of this particular puzzle turned up, both in the archives of a Madison newspaper, the Wisconsin State Journal. First, a classified ad for a used car and then, discovery of a second, pertinent “Madison Day by Day” social column by Cass.

A July 22, 1936 classified ad for Kayser Motors, Inc. located at 701 Washington, listed the following: “1935 Ford Cabriolet—has set of 1936 wheels. Brand new tires that have never been driven. Car finished in Cherokee Red. Exceptionally low mileage.”

According to Herink, the Wright’s not only owned the two 1935 Fords, of which this is certainly one, but also three 1936 Fords; a convertible sedan and two station wagons. The car’s description and date of the ad fit the timeline perfectly. But what makes it incontrovertible as formerly owned by Wright, is the stated paint color applied to this used, 1935 Ford. Cherokee Red was never a Ford paint color. As you’ll see later in this piece, the only Fords ever to be painted Cherokee Red were those custom ordered by one, Frank Lloyd Wright.

In November of 1935, Cass wrote a follow up to her, apparently controversial, August piece on the Wright’s “Ripe Persimmon” Fords, in which her initial claim is challenged.:

November 14, 1935 – Madison Day by Day, by Betty Cass

Bill Whitney, of the Pyramid Motor company, explains the controversy over the color of Frank Lloyd Wright’s two Ford cars…the color which I said was copied from a pottery cream pitcher which the Wright’s brought back from Arizona last winter…and which Mr. Whitney said was copied from this year’s Oldsmobile convertible coupe…like this:

“Yours of the 12th re Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright Cherokee Red” Ford Coupe just received. Carefully noted, read and reread.

You win!

But by the way of explanation in the matter of the Cherokee Red color, which is used exclusively this year on the Oldsmobile Convertible Coupe, may I add a word?

One of the color men from the Oldsmobile Factory at Lansing was making a trip through Grand Canyon and Arizona and he noticed an Indian squaw making pottery from clay which was a certain color when wet, and a different color, more beautiful when dried and hard: he took a sample of this clay back to the factory; they experimented with pigments to produce that color as nearly as possible; the result was our Cherokee Red.

And which is the most beautiful color, when it is studied carefully, that I have ever seen on an automobile, regardless of price.

Just the same—some real hot day I’ll buy you a fine lime freeze—no foolin’.”

According to that, we both win, Bill…don’t we? The Wright’s car WAS painted with Oldsmobile paint, but Oldsmobile paint was copied from pottery in Arizona…and contrawise (as Tweedledum says) the Wrights had to take their Arizona pottery pitcher around with them until they found the paint to match…but I’ll take the lime freeze anyway. What’ll you have?

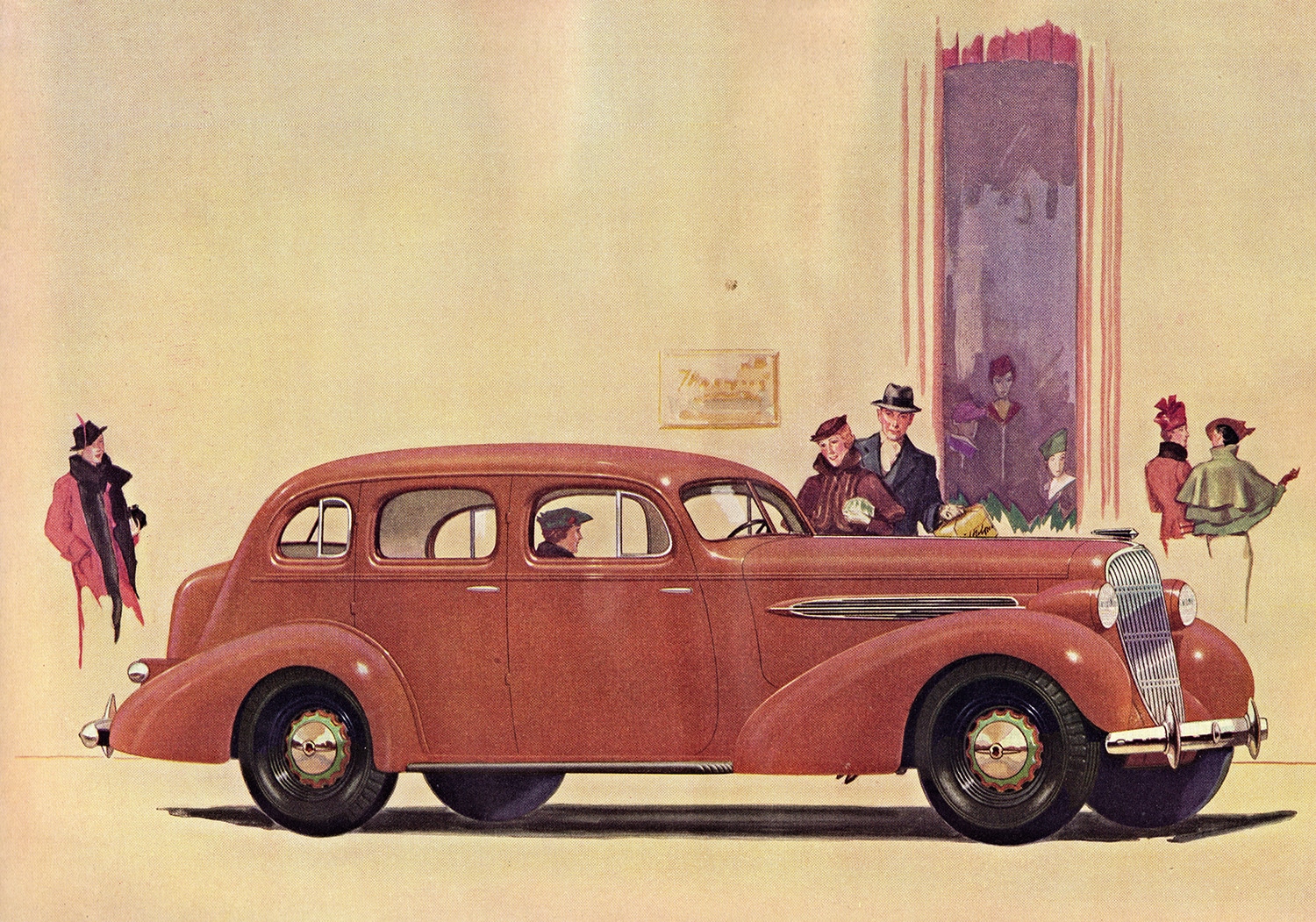

Sales brochure image of the 1935 Oldsmobile Eight four- door Touring Sedan in Cherokee Red. Touring Sedans had an exterior trunk like the Ford humpbacks, for additional carrying capacity. Alden Jewell via Creative Commons

There is a considerable swath of color space between the Olds Motor Works Cherokee Red and the Catalina Island Pottery, Toyon Red glaze that inspired Wright. A 1935 letter from Taliesin to the Ford Motor Company calls out the Olds Cherokee Red and makes no mention of an enclosed cream pitcher. Still Betty’s description of the cars sounds so Toyon. Only examination of the actual car, the one featured in the classified ad, would prove the original shade. But, in case this is not yet abundantly clear, I’ll state it once again, there are countless variations on the color called Cherokee Red, as Wright and his associates used it between 1935 and 1959. My guess is even more, after.

Whitney’s explanation, ties the Olds paint color, which must be considered the legitimate specification source of Cherokee Red, to its deeper origins, Native American pottery, which has been another popularly cited source. The only difference is that it was not Wright mailing pottery around the country. It was a color technician in a lab color matching to examples of some clay pieces he, himself happened upon and carried home to Detroit.

Whitney played an active role in Madison community affairs, serving as president of the Wisconsin Centennial Celebration in 1936, chairman of ways and means committee of Madison Shriner’s and as an active University of Wisconsin Alumni. He was then, a well-known independent automotive entrepreneur in Madison. His dealership, Pyramid Motors, dealt in General Motors automobiles and on April 16, 1937 it was sold to GM Holding Corp. Whitney’s insider knowledge of the history of Oldsmobile’s Cherokee Red, would have been conveyed to him via his business ties to GM, combined with his understanding of the current Olds line up. Whitney even knew the specific Oldsmobile “Convertible Coupe” model it was offered standard on. But then there is Cass, who let on in her second piece, that the cream pitcher was “brought back” from Arizona by the Wrights, the previous winter. That makes the Biltmore gift shop an even more likely candidate for where the cream pitcher first caught Wright’s eye.

As mentioned in part 11 of this series, the contemporary PPG Frank Lloyd Wright palettes offer three variations of Cherokee Red, the original (PPG13-02), one specifically for Taliesin West (FLLW68), and another for Fallingwater (ATC-5). Independent of these, Fallingwater has identified several reds, each with its own unique formulation based on their own historic paint research. Why should it be surprising that Wright’s Cherokee Red cars were not identical in hue? In part 16 of this series, I included two photos of Taliesin cars, each painted in some form of Cherokee Red; a 1955 Gullwing Mercedes 300SL owned by Wes Peters and the iconic, customized 1940 Lincoln owned, crashed and then modified in 1947, by Coachcraft Ltd. in Hollywood, California for Wright. The 300SL is interesting in that it resembles the burnt red-orange shade inspired two decades earlier, by Catalina Island Pottery. Any assumption that Wright’s or indeed Taliesin’s color tastes flowed in a single direction, can certainly be dismissed. Further evidence can be seen in the photo of the customized 1940 Lincoln included in that second post. It also appeared to be painted in a more sanguine color at a later stage in life, possibly re-colored in 1947 when the custom, coupé de ville, half-top was added.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s fully restored, 1940 Lincoln with custom, coupé de ville top at Auldbrass Estate. Photo by Tom Heinz

I reached out to Joel Silver who now owns this custom Lincoln, as well as another of Wright’s Lincolns. He put me in touch with Scott McNair, the estate manager at Auldbrass, in Yemassee, SC, where the cars are housed. McNair described to me the sorry condition that the customized Lincoln was in when Silver purchased it, and made special note of the unappealing color it had been painted. During the course of a thorough restoration, they fortuitously uncovered, deep within the bodywork, a panel painted in the original, factory-applied Cherokee Red color. This is the paint sample they color-matched to, and rightly so. Who can say what reference was sent to Lincoln when this car was initially ordered, but the resultant, deep lustrous red color-match, leans in the direction of the classic 1935 Olds Motor Works Cherokee Red.

Cherokee Red paint can be found in abundance on painted surfaces at both Taliesin and Taliesin West. It presents itself as being more muted than any of the automotive finishes. Enamel car paint possesses an innate depth and luster that the opaque house paint formulations of the same color simply cannot approach. Whitney’s claim that Cherokee Red was “the most beautiful color, when it is studied carefully, that I have ever seen on an automobile, regardless of price.” Raises the question, why was this paint scheme was not adopted by other automobile manufacturers? Turns out it was.

Following Oldmobile’s lead, automobile manufacturers in the 1940s and 50s included Cherokee Red in their color charts. This ad is for a Cherokee Red, 1952, dual-range Pontiac Convertible. Via Newspapers.com

What I perceived as a mismatch in the DUCO paint color code that Masselink sent to the Ford Motor Co., versus the reference numbers found on the actual Olds Motor Works 1935 color chart, led me to a fortuitous site in my online search, paintref.com a website that cross-references historical automotive paint colors. I found the original, 1935 Olds red. The listing included both reference numbers, alleviating the confusion. But on the site I discovered something more. Cherokee Red appeared as a paint option, offered by a number of manufacturer’s across model years, albeit in varying hues. The formulations generally trended slightly lighter and brighter over time. The 1955 Buick and 1960 Lincoln versions of Cherokee Red are the only two in the list that skew well out of the range of Taliesin’s Cherokee Reds.:

- 1935 Olds Motor Works

- 1948 Studebaker

- 1950 Studebaker

- 1951 Studebaker

- 1952 Studebaker

- 1952 Pontiac

- 1952 Willys

- 1953 Studebaker

- 1954 DeSoto

- 1954 Studebaker

- 1955 Buick

- 1955 Studebaker

- 1960 Lincoln

- 1980 Volvo

In his book on Wright’s automobiles, Herink suggests a color introduced by Nash Rambler for 1951, manufactured incidentally, in my hometown of Kenosha, became the successor to Cherokee Red at Taliesin. It was a color named Pan American Red. I am not sure what the basis of his statement was. I was unable to verify the claim. According to record, Wright never owned a Nash or a Rambler.

However, I will admit the paint color, Pan American Red is but a stone’s-throw from the darker shades of Catalina Island Pottery, Toyon Red. In yet another social column, Cass described a different Cherokee Red vehicle that appeared one day on the Madison scene.

Three relative color samples, (left to right): 1952 Pontiac Cherokee Red, 1934 Olds Motor Works Cherokee Red, 1951 Nash Pan American Red. Photo by Steve Sikora

September 12, 1940 – Madison Day by Day, by Betty Cass

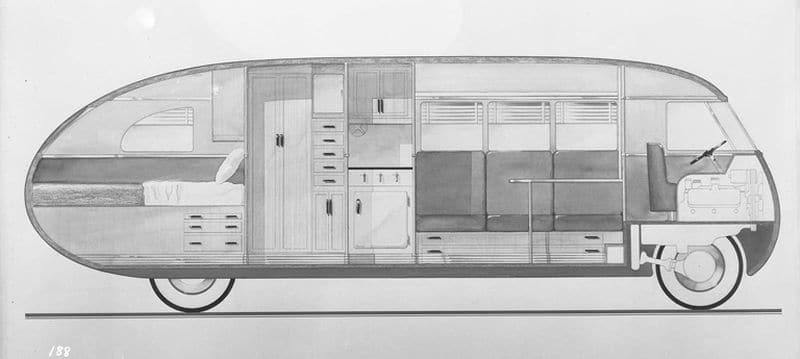

That sleek sophisticated Cherokee red Land Yacht which has been cruising around Madison streets today creating so much interest and speculation is the house-car (it would be a sacrilege to call it a “trailer”) in which Herbert Johnson, head of the Johnson Wax company at Racine, will make a trip into the interior of Brazil to do research work in connection with carnauba wax which is used in Johnson waxes.

And anyway, it isn’t a trailer. It is all built into one, long, low streamlined unit, with the driver’s compartment opening from the living quarters I the same way in which the pilot’s cabin on an airliner opens from the passenger’s section. Designed by Brooks Stevens, the young man who designs those beautiful cars which Esquire features, it has Timkin front wheel drive which gives it a very low floor and plenty of interior headroom without much exterior height.

The Cherokee Red Johnson Land Yacht built by Brooks Stevens for Herbert Johnson. Photo courtesy Milwaukee Art Museum

In the roof are skylights for natural ventilation, although it is completely air-conditioned for both heat and cold when necessary. Immediately back of the driver’s compartment is a very masculine living room or study, with a built-in desk of natural wood, a long leather-cushioned seat down one side, built-in radio and attachments for setting up a dinner table, and venetian blinds.

The efficient interior layout of the Stevens-built Clipper. Photo courtesy Milwaukee Art Museum

Back of that is the most compact kitchen imaginable, the whole being about 30 inches wide and just head-high, with a roomy refrigerator near the floor, a gas stove on top of that, and cupboard space above that. Across the car from it are more cupboards, with a stainless steel kitchen sink on top.

Back of the kitchen space on one side are clothes and linen closets, and on the other side a bathroom, complete with shower.

And in the rear end of the car, which is beaver-tailed like the streamliner trains, there are two bunks which are thirty inches apart at the heads but come together at the foot.

In these rooms, as in the study, there are no frills, everything being purely functional and thoroughly masculine. The only concession to decoration, which Mr. Stevens made in designing the car was to use the beautiful Soft Cherokee red, which is the color of some natural clays, entirely on the exterior, and in several places of the interior. This is the same red used at the Johnson plant at Racine, designed by Wright, and on all of the automobiles which Johnson salesmen drive. It is also the same red, you probably remember, which Mr. Wright uses on all of the cars which belong to him and to the members of the Taliesin fellowship at Spring Green.

In all its streamlined glory, the 1940, Cherokee Red Herbert Johnson took to the New York World’s Fair. Photo courtesy Milwaukee Art Museum

Mr. Johnson has just returned in the land yacht from New York, where it created a tremendous sensation at the fair and was probably the most photographed vehicle there the whole summer. Not only did the fair itself send special photographers to take numerous pictures, but several other larger companies “borrowed” it for several days each to photograph and use in their exhibits.

Before Mr. Johnson leaves for Brazil with the car, it will be given and extensive trip on American roads, including those of Mexico.

Hoff. Via Newspapers.com

Cherokee Red was unofficially adopted as emblematic of the SC Johnson brand. To this day, no other client, much less a corporate entity, ever did as much to support and elevate Wright and his ideas. This, in no small part, helped create awareness for this particular red color in the minds of the consuming public. As far as Nancy Willey’s prediction that the world would soon know the color Cherokee Red—there are good reasons to believe that its popularity was boosted, along with Wright’s own ascent from infamy to fame, and his lavish use of it on his daring new, feats of architecture. In January of 1938, a trio of magazines featuring the current work of Wright, simultaneously hit newsstands. Time Magazine profiled Wright “the greatest architect of the 20th Century,” The Architectural Forum was a special, 74-page issue devoted exclusively to his work and philosophy.

Life Magazine featured a full-page display ad, promoting the January issue of the Forum, showcasing one dramatic photo of Fallingwater featured in the issue. This unprecedented barrage of unmediated press coverage came courtesy of the Johnson Wax Company. This marketing blitz was initially intended to promote their new headquarters, but since the extraordinary Johnson Administration Building was not yet completed at time of publication, the focus shifted to Wright himself, his school, his belief system, his buildings and their peculiar red color coloration.

A search of period newspaper advertising, soon after 1938, produced instances of Cherokee Red coming into common use in the production of consumer goods, as a long-lived “trend color” throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Examples include:

- 1940: Johnson Wax marketed the 75c Kleen Floor Duster, with large oil-free head of Cherokee Red cotton yarn and a sturdy 54 inch handle. Just 49 cents.

- 1942: Harry S. Manchester, Inc., a Madison, Wisconsin fabric shop sold Wesley Simpson Custom Fabric in American-Indian inspired colors including Cherokee Red.

- 1945: Geenen’s Dept Store in Appleton, Wisconsin sold Wembley Ties in Cherokee Red for $1

- 1947: Newburg’s of La Crosse, Wisconsin, Wisconsin’s Largest Men’s Store, sold moccasin-style Freeman Shoes with Cherokee Red Cobble-sewn Seams.

- 1948: Krueger’s in Neenah, Wisconsin sold Oshkosh Luggage “for Her” in Cherokee Red

- 1949: Mailmaster mailboxes from Racine Specialty Manufacturing Co. were available in Cherokee Red for $14.95.

- 1949: The Johnson’s “Beautiflor Electric Polisher finished in Cherokee Red, just $44.50, was sold at Mohr-Jones in Racine, Wisconsin, “The Logical Place to Buy Appliances.”

- 1956: Hoffer Glass & Paint of Green Bay, Wisconsin ran ads that read: “Thrill to the matchless Beauty of Hoffer’s BEAUTIFLO Rubber Satin Finish in 16 Lovely Color Tested Shades.” Naturally those shades included Cherokee Red.

- 1956: Fleet of delivery trucks for Rahr Beer of Green Bay, Wisconsin were all newly decorated with lower panels painted gold, upper panels in white, and the Rahr Crest in Cherokee Red.

- 1957: Retail ad in Tucson’s Arizona Star ran a display ad for women’s shorts in Cherokee Red.

Geenen’s Wembley Ties. Via Newspapers.com

Dress up the home this holiday season with a Mailmaster mailbox in soft Cherokee Red. Via Newspapers.com

Prior to 1935, there was scant evidence of a color called Cherokee Red that also dwelt in the spectral range Wright favored. The name, Cherokee Red, did however exist in the field of floriculture. In a 1930 Arizona Star article, resident gardener, Harry Bateson advocated for more parks and flowers, for the year-round beautification of Tucson.

Among the climbing roses available from local growers in the specimen list he included was Cherokee Red, a single bloom, red rose. I doubt that the hue corresponded to iron oxide reds we are concerned with in this history, but the name was clearly established. Where and when did it originate?

Though the appellation rings of cultural appropriation, it seems there is nothing resembling the color quality of Cherokee Red in the ceramics of the Cherokee people. Who can say where it was first used? Maybe a pigment found elsewhere in the tribal milieu, a slur, in reference to skin tone, or some fictional idea born of Hollywood Westerns, though the Cherokee people were not a western tribe. It could simply be a cooked up marketing phrase, designed to stir the soul, in promotion of railroad expansion west. Or it could have just been a rose. Any or all of the above are possibilities. For certain, the name Cherokee Red was not coined by an Oldsmobile paint man driving through Arizona, because it was already part of the zeitgeist. Like the color samples he collected, he seized upon the term in some corner of the world at large, and carried it home with him, its true etymology a mystery.

There is a Chinese proverb that can be traced back to Lao Tzu: “Name the colors, blind the eye.” In other words, if we only “see” the colors we put a label to, we tend to “un-see” other possibilities in an infinite spectrum of color.

That wasn’t exactly true of Wright. For him, the name Cherokee Red was unwavering, but it was the color Cherokee Red that continually evolved or morphed, as required or desired. As Cara Armstrong, a former Curator of Buildings and Collections at Fallingwater wrote, “Although Cherokee red is found in many Wright buildings, the true color actually varies from location to location, depending on the light, climate and the material on which it was used.” Wright had a knack for remaining open to the opportunities of the moment, and had no hesitation changing, reconsidering or refining any thing at any time, as he saw fit.

That included his definition of Cherokee Red. Despite the countless interpretations and broad as the range is, the thing that is common to every iteration of Cherokee Red is iron oxide pigmentation. Iron oxide is what defines this family of colors. Still, one can only imagine the eyes darting around the Taliesin drafting room whenever Wright specified Cherokee Red. How on earth did they know what he wanted?

A pentimento gas pump, in the upper parking court at Taliesin reveals the remnant stratum of assorted Cherokee-like Reds applied over the decades. The adjacent wall is painted in the official color, used in exterior trims throughout the estate. Photo by Steve Sikora

Pipework trellises and gates located about the main house at Taliesin, painted in Cherokee Red with Taliesin Red cube accents. Photo by Steve Sikora

To summarize the findings of this meandering inquiry: All roads do point in the direction of the 1935 Olds Motor Works color chart, as the original specification source for Cherokee Red. It is the verified formulation supplied to both the Willeys and the Kaufmanns, and though there were antecedents, only the Olds color chip can be considered the bona fide, original that Wright used at these houses. Moving forward, Wright’s obsession with the color, coupled with the marketing strength of the Johnson Wax Company, a host of trend people and later advocacy from House Beautiful magazine, fired consumer’s imaginations with fever-dreams of Cherokee Red, encouraging decades of subsequent use.

Elements of earth and fire underlie the sublime quiddity of Cherokee Red. It is born of the soil and indigenous to places that were home to Wright. Cherokee Red evokes equally, the stark, savage beauty of the American West and the lush serenity of a rural, Wisconsin barn. Wright did not invent the color Cherokee Red.

He did not name it. He was not the first to use it. But after discovering this particular, smoldering, earthy red-orange hue, he embraced it with such fervor and persistence, that he certainly helped to elevate it to the category of household name.

Subconscious inspirations for Wright’s adoption of this favored color can be traced, like so many things, to his youthful impressions of Wisconsin, to the blazing palettes of Arizona, to the earth-drawn materiality of Native American arts and crafts, which he relished and collected, and to the use of this iron oxide pigment by literally every ancient culture that ever lived.

It is however, now clear that Wright happened upon it while seeking a distinctive paint scheme for two, new 1935 Fords, that he and Olgivanna were about to order. Wright’s conscious awakening to Cherokee Red, occurred first at breakfast one morning, and then on the bodywork of a gleaming Oldsmobile, either paused at a traffic signal in Phoenix, or on display in a showroom somewhere in or around Milwaukee.

The massive Dutch-door to Wright’s drafting studio and window trim at Taliesin, painted in Cherokee Red. Photo by Steve Sikora

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains

Part 14: Separated at Birth

Part 15: Trading Drama for Poetry

Part 16: A Red By Any Other Name

Part 17: Roll Down to Levittown