Willey House Stories Part 15 – Trading Drama for Poetry

Steve Sikora | Jul 25, 2019

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

“Every great architect is – necessarily – a great poet. He must be a great original interpreter of his time, his day, his age.” – Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright wrote and lectured extensively about poetry in architecture. His poetry described an economy of form and eloquence of expression that exposed the deepest natural truths as profound beauty. Evidently the concept of poetry was a topic of discussion when it came to the design of Nancy Willey’s future home as well. Willey House scheme one was a two story design that reluctant, Twin Cities builders estimated at nearly double Nancy’s budget, unaffordable, even in the stagnant economy of the Great Depression.

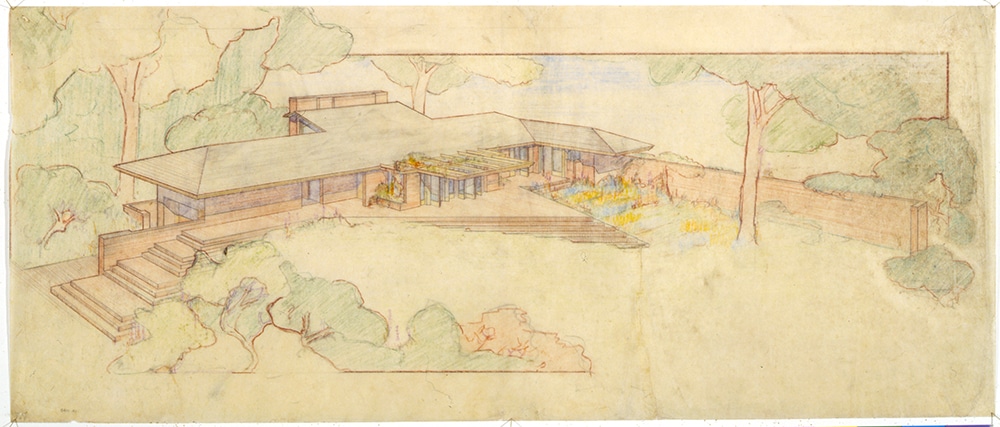

Willey House scheme one presentation drawing, 1932. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

It featured a dramatic second story balcony, a soaring extension of the living room floor that visually connected the house to the Mississippi River and the distant southern horizon. Equally dramatic, it seems, was the cost, $17,000 to $20,000. Nancy Willey told Wright she was unwilling to “poison her joy” in her Wright house by shouldering “obligations greater than one was willing to bear.”

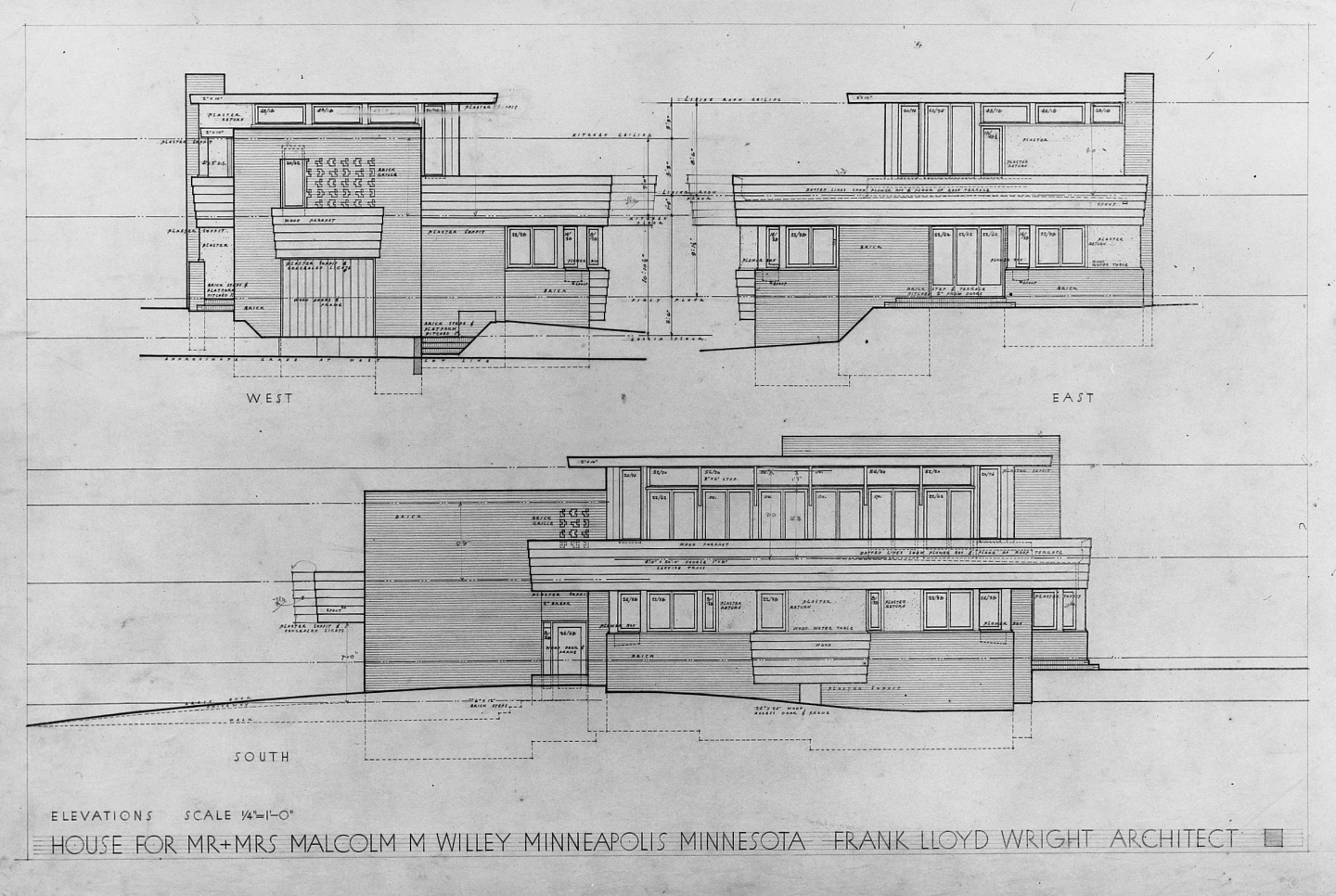

Willey House scheme one elevation. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright

Taliesin, Spring Green, Wisconsin.

My dear Mr. Wright:

Thank you for replying so promptly. I appreciated it, as I believe we have no time to waste now. I should have answered as quickly, but I didn’t at first know what to say. I have thought about it all week, and this is the result.

I do not want a seventeen thousand dollar house even at twelve or ten thousand dollars. I want an eight to ten thousand dollar house at eight to ten thousand dollars. Can I have it? What I mean is this: if I could put the bricks down myself side by side and with my own Herculean efforts help to build the house I would indeed rise to the challenge, for I am very, very much in love with it too. But I can’t do that. I am only a client and, as far as I can see, the only Herculean efforts a client can make are in the nature of…shouldering obligations greater than one wanted in the first place…a role which I feel is a mean one and in the end would poison the joy in the house itself. We place such a high value on having a Frank Lloyd Wright house that we are not unwilling to poison our joy in it by having too large a debt on it, and we will always feel that way. The procedure you suggest to avoid the curse of the contractor I would love to follow if it were not for the above money factor. I would love to do it to make an example of freedom from the archaic system we now have. But even if I felt pretty sure we could affect economies that way, I couldn’t do it because there would be no certainty about the final cost and we just can’t take a chance. We must know how much it is going to cost, at the beginning. Building in two parts is probably impossible because we could never get credit for half a house. If we should want to leave Minneapolis it would be un-saleable, and the expected inflation promises heavier building costs than at present. We do want a whole house now, even if it is a very small simple one. I could come down to Taliesin anytime, but I do feel that drastic simplifications are the next step. Perhaps we could set this house aside and say, maybe somewhere, sometime the Willeys can build this house, who knows? But the 1934 house will have to be even a simpler gem. And we do want a 1934 house!

Our best wishes to you and Mrs. Wright,

Sincerely yours,

Nancy Willey

November 26, 1933

In resignation, Wright responded:

Dear Nancy Willey: We’ll try again. It seems the simplest way. My best to the other half. And we’ll let you know when to “drop in” — on a weekend when the playhouse is in action.

Sincerely yours,

Frank Lloyd Wright,

TALIESIN: SPRING GREEN: WISCONSIN: NOVEMBER 29

Willey House scheme one presentation drawing, 1932. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

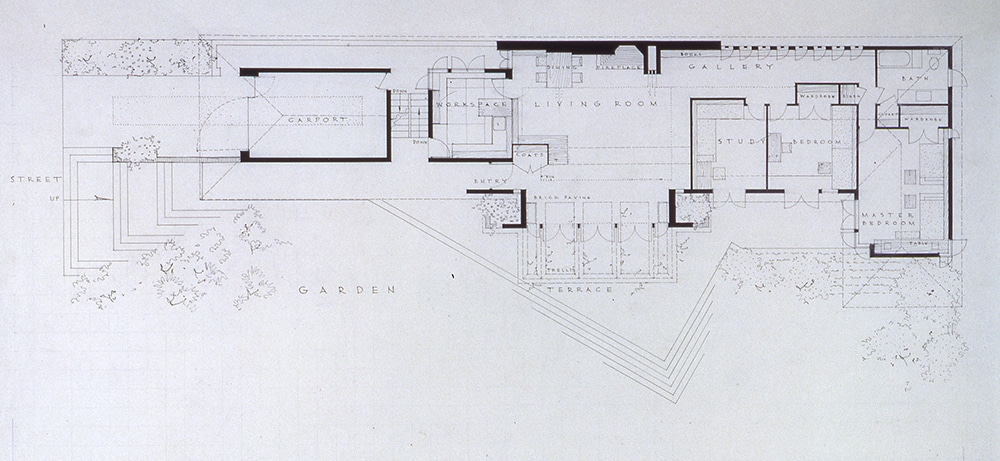

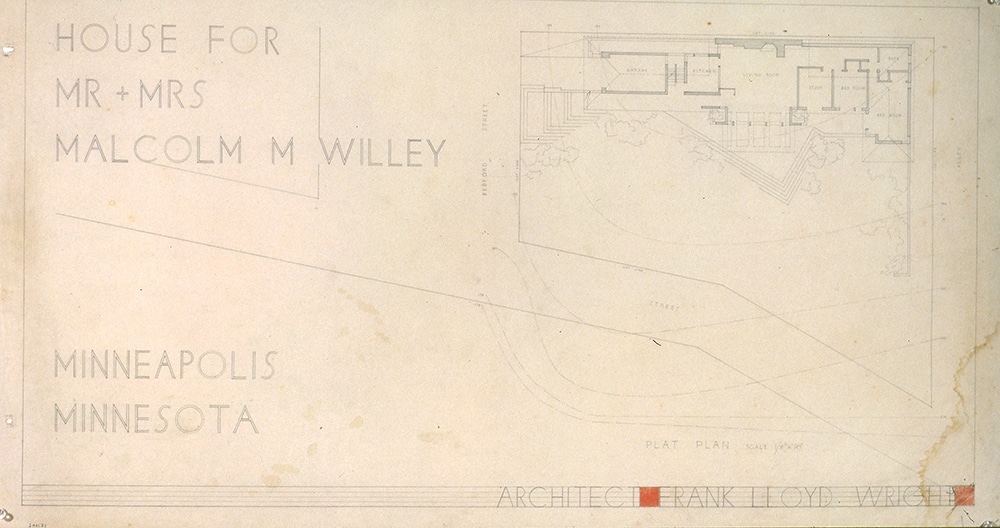

Willey House scheme two plan. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

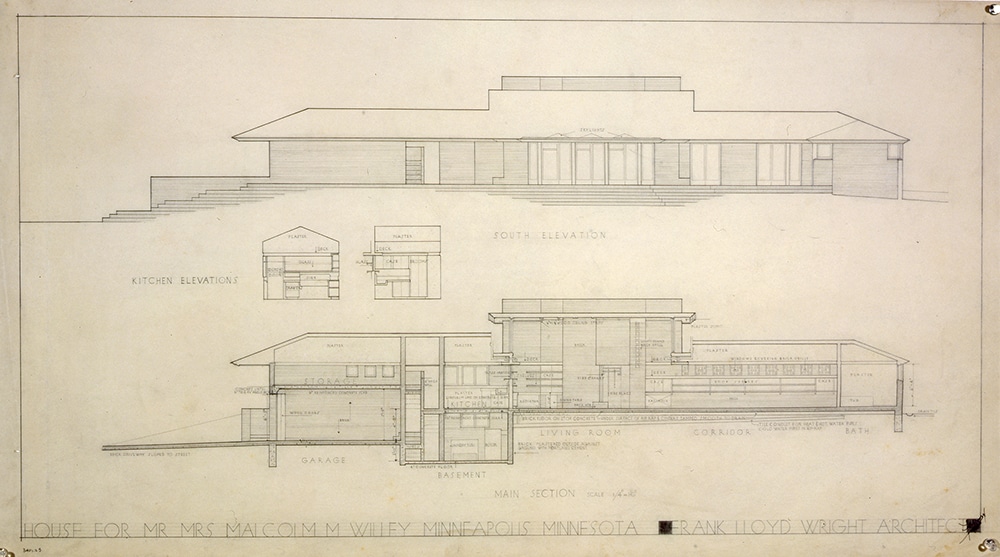

Willey House scheme two elevation. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

Wright agreed to redesign, and submitted a radically different alternative just a few weeks later. The new scheme deviated completely from the original proposal. The only similarities were that both designs fully exploited the sweeping southern vista and both utilized a five-foot square, planning module. Nancy was overjoyed and shared the new plans with friends.

Whether the sentiments were entirely her own, or those of her friends, she conveyed them succinctly when she wrote to Taliesin:

I haven’t said how much we like it. I take that for granted. Mr. Willey is thrilled and so am I. Our friends say they like it better than the first house. Perhaps they can understand better poetry in houses than drama! But I was pleased when my best friend said it was the most beautiful house she has ever seen.

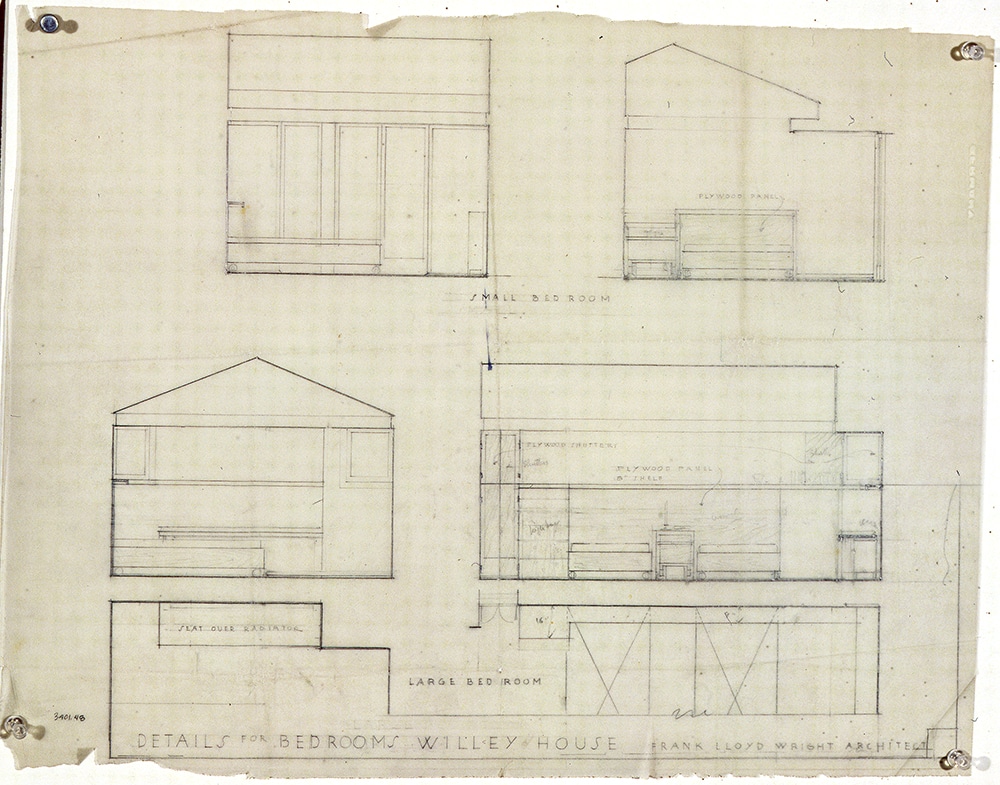

The thread of “poetry” weaves itself through their letters as the house begins to take shape. In 1934 Frank Lloyd Wright is already trying to minimize the use of stand-up, cast iron radiators. When eliminating them is not possible they are cloaked in various kinds of enclosures, or better yet, buried.

Willey House living room and southern vista 1936. From Nancy Willey’s photo album.

January 6, 1934

Dear Nancy Willey:

Apropos of heating. I see our “engineer” is old fashioned. He believes in directly heating up the outside walls. This idea was scrapped long ago. Please ask the venerable gent, to stick to the locations provided in the plans, modifying the study, bedroom and own room as herewith. The exposed radiators in outside wall of living room are poetry crushers. They must be sunk in wells as indicated. He will kick about this, being what he is, and talk about clearing out the well etc. etc. etc. mice et cetera.

Faithfully yours

Frank Lloyd Wright

Taliesin Spring Green: Wisconsin: September 15

Cautiously avoiding any misstep that could threaten architectural poetry, Nancy complied whenever possible to Wright’s directives, even when it meant adding a pump to the heating system to satisfy a specification that the heating contractor was wary of.

…With the radiator entirely sunk we now have the entire space cleared for poetry. I’m sorry, if Mr. Wright wanted to try the half-sunk design but it was necessary to decide quickly.

Any orders about the metal grills?

Sincerely,

Nancy Willey

10-2-34

The Willey House was the only outside commission in the first years of the Taliesin Fellowship. Scheme one was drafted under the supervision and sure hand of Henry Klumb. For five years, Klumb had considered himself lead draftsman at Taliesin (his words, not Wright’s). He is sometimes credited with that same role on the second scheme; unfortunately he had already left Taliesin by that time. This is corroborated in the introduction of “At Taliesin,” in which Randolph C. Henning includes a passage from a December 2, 1933 letter from Wright to Henry Klumb. “…have redesigned the Willey’s House and they will now get poetry instead of drama. Drama always comes high, I guess.” Wright would not have needed to announce the redesign and resulting effect to Klumb, if Henry had himself completed the work.

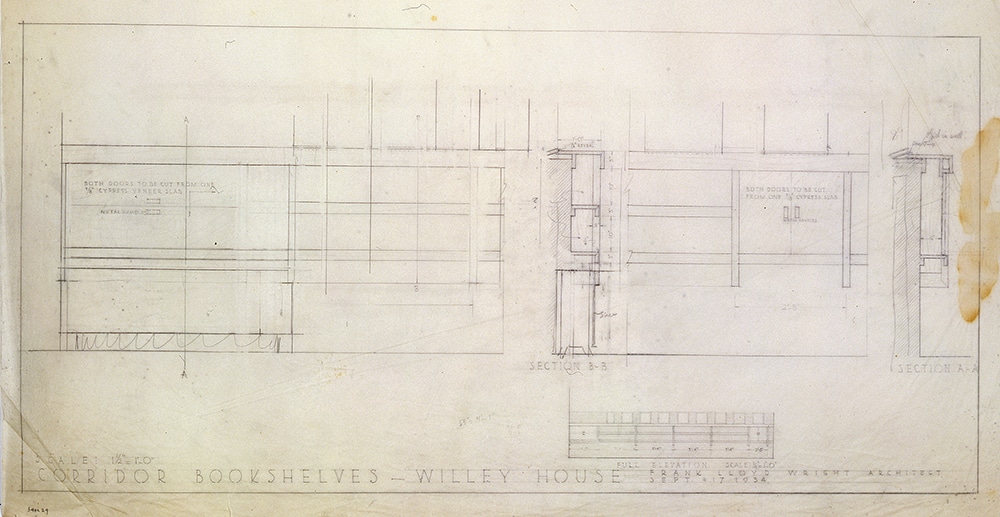

Good evidence of who did not draft the scheme two drawing set can be found in the drawings themselves. The archive at Columbia’s Avery Library contains two sets of plans for the Willey commissions. 45 sheets were drawn for scheme one and 54 sheets comprise the scheme two set. Additional scheme two drawings exist outside the archive.

An unwavering sense of consistency in terms of line quality, lettering style and the treatment of title blocks are hallmarks of the scheme one drawings. In contrast to the first, the plans for the second scheme, though also well drawn, appear more arbitrary in layout and execution. There is an undeniable, uniform quality to the 1932 plan set, that is unmatched in the 1933, scheme two drawings. The difference can be accounted for by the lack of professional draftsmen at Taliesin after September of 1933. The inconsistencies in sheet size, drawing style, and title block formats, imply a wholesale change from the way things had been done under the guidance of seasoned professionals. It is evident that many different draftsmen worked on the Willey House plan set. Based on this revelation, scheme two marks the precise moment in time when the Taliesin Fellowship took ownership of the drafting room, working directly under Wright’s personal direction.

In a February 17, 1934 progress letter to Nancy Willey, Wright states:

“We are giving the plans our very best and they are nearly done—Every little detail is having first hand consideration. Five men have been “at it” for several weeks past—and it is ‘such a little one’ at that.

Thank you for your loyalty and may you be glad you were—I mean are—”

If the highly seasoned Klumb was not in charge of the drafting room for the rendering of scheme two, then who was? It is commonly understood that John (Jack) Howe became Wright’s right hand man in the drafting room at some point, but in late 1933 he would have still been very young, with little actual drafting experience under his belt. Until Howe matured, no one but Wright himself could have directed the proceedings.

Presentation cover sheet Willey House scheme two. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives

Bookshelves detail sheet Willey House scheme 2, by John Howe. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

Willey House scheme 2 fireplace plan. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

Willey House scheme two bedrooms detail sheet. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

The three professional draftsmen who had been formerly employed, if “employed” is the right word, by Wright during the founding years of the Fellowship were: Henry Klumb of Germany, Robert Goodall from Chicago, and Rudolf Mock who came from Switzerland.

The three professional draftsmen at Taliesin – Klumb, Goodall and Mock, all of whom were listed as fellows, left within the first two years of the Taliesin Fellowship, each for their own reasons.

Mock, a professional architect born in Basel, Switzerland, was the first to go. He became enamored with Elizabeth Kassler, one of the early apprentices. They left Taliesin and married. Mock worked as a designer at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Elizabeth Kassler Mock later went on to become the Director of Architecture and Design at MOMA. The couple departed Taliesin in April 1933.

Klumb, of Cologne, Germany, began working with Wright in 1927. He managed the drafting room for the five years he was in residence. Klumb’s wife, Elsa, was also listed as a member of the Taliesin Fellowship. It was Klumb who convinced Wright to show his works in stark black and white perspectives for the Princeton Lectures of 1930. With Wright’s blessing, Klumb and Takehiko Okami of Japan rendered six selected buildings that included Larkin, Winslow, Unity Temple, Robie, Bock Ateliers and a Small Town Hall in this dramatic style. Klumb was lead draftsman for the first Willey House scheme done in 1932. But he departed Taliesin before December 1933 unhappy with his inadvertent role as drafting teacher. Edgar Tafel reported that Klumb left in September of 1933, saying he had “had enough of the kindergarten.” Upon his departure, Klumb formed a partnership in Brainerd, Minnesota with another Wright associate, Stephen Arneson.

The last of the three, Goodall, hailed from Chicago, Illinois. Alden Dow, an early a member of the Fellowship, said that Goodall was the best draftsman he had ever seen. Goodall bid Taliesin adieu to work with Dow in Midland, Michigan, where architectural work was plentiful. In the book, “Frank Lloyd Wright Remembered,” William Beye Fyfe remarked, “Some of the most beautiful architectural drawings in the world would come out of his studio. Bob Goodall was just the best draftsman I’ve ever seen in my life…Mr. Wright wouldn’t touch us because Bob was a faster draftsman.” A demonstration that in the first year of the Taliesin Fellowship Wright left the primary drafting tasks in the hands of the professionals while he had them. Edgar Tafel’s book on Wright includes a photo from Goodall’s farewell party in Spring Green, the group posed standing on a sidewalk, indicating that it was taken sometime late in 1933. All present are garbed in cold weather dress. A patent drawing, signed by Goodall, illustrating Dow’s unit block system, dated December 5, 1933 confirms that Goodall too, was gone before the scheme two of the Willey House.

On Wednesday, July 20, 1932, when Nancy Willey made her first trip to Taliesin, there were no more than 13 charter members in the Taliesin Fellowship, none of them in the drafting room. By late 1933, as the second scheme for the Willeys was being conceived, there were over 30 young people now in residence, each as anxious as the next for a break from farm labor and kitchen chores. Members of the Fellowship were aching for the opportunity to do some actual, hands-on architectural work in the studio. With the professional staff finally gone, all that was needed was a project. The Willey House scheme two was exactly what they were waiting for.

Terrace and garden wall circa 1937. From Nancy Willey’s photo album.

According to Howe, “There were eight drafting tables in the old Taliesin studio, and Mr. Wright would move from one to another of these, working with each apprentice on whatever projects were on each table. Mr. Wright usually started the design of a building on the surveyor’s plan of the property, which showed the contours of the land, trees to be saved, rock outcroppings, or other natural features such as orientation, or points on the compass. So again, the land was indeed the beginning of architecture.”

Howe explained his rise in stature, “in 1932 and 1933, when the studio was still manned by faithful draftsmen who had been at Taliesin for a number of years, I began to put the drawing files in order. I also worked on whatever drawings these draftsmen would give me to do. The Malcolm Willey House for Minneapolis, new buildings for Hillside (the old Hillside home School near Taliesin), Broadacre City, and the Two-Zone House were the projects on the drafting tables at that time. Subsequently, after these draftsmen had left Taliesin, I found myself more or less in charge of the studio for two reasons: one, I knew where the drawings were, thanks to my filing system; and two, I somehow managed to be there whenever Mr. Wright would come in.” Howe, the youngest of the fledgling Fellows recalled, under his tutelage, being assigned to certain details of the Willey House; namely the kitchen cabinetry, the gallery shelving unit and the fireplace armature. He repeated the story frequently. Eventually Howe became the favored “pencil in the master’s hand.” Wright even had him sleeping in the “loft” above the drafting studio for a time, that is to say on the platform above the vault, so that he wouldn’t need to disturb the household when he summoned Howe to work in the pre-dawn hours.

In “The Fellowship,” Abe Dombar recounts being called to the drafting room to work on the Willey House redux, unfamiliar with its workings because he’d spent so much time doing farm labor, but being comforted by the fact that Klumb was there to guide the process. Good story, but unfortunately, his recollection, if it was his, doesn’t fit the timeline. Klumb left Taliesin in September 1933. Dombar may have been confusing scheme one and two. The redesign of the Willey House began November 26, 1933 at the earliest, based on the correspondence between Wright and Nancy Willey “We’ll try again. It seems the simplest way.” Final corroboration comes in the December 2 letter from Wright to Klumb informing him of the redesign. It is certain, that by November 1933 there were no professional draftsmen in residence to man the studio. What remains uncertain, is who the five, young men assigned by Wright to draw the scheme two plans were. Without a doubt Howe was one of them. He was able to cite every detail he had been responsible for. Because of his experience detailing the first scheme under Klumb, Dombar was probably another. Tafel and Bob Mosher, both there, also seem likely candidates, but harder to verify. The second Willey House plan fulfilled the promise of actual studio experience for the early Fellowship. It coincided with that long-awaited opportunity, of working, as the brochure promised, side by side with the master, pencils ablaze, complicit at last in his quest for achieving architectural poetry. For Nancy Willey, settling for poetry was hardly a compromise. After all, she never asked for drama and didn’t need more of that in her life than she already had. She asked for a house that would facilitate a modern, simple and gracious way of living. And in the end she got a house, perfectly suited to her needs.

Bedroom wing of the Willey House circa 1930s. From Nancy Willey’s photo album.

Nancy Willey’s voice resonates clear as a bell in the June 1935 issue of the Minneapolis based, Golfer and Sportsman magazine, where Editor, Virginia Safford, profiles the already mythical Willey House in a particularly thoughtful, five-page story. In her dialogue with Nancy Willey she notes and reiterates a now familiar expression that perfectly described the Willey House then as it does today: “If the first house had been drama, the second was poetry.”

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains

Part 14: Separated at Birth