Willey House Stories Part 14 – Separated at Birth

Steve Sikora | Jun 11, 2019

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” – John Muir

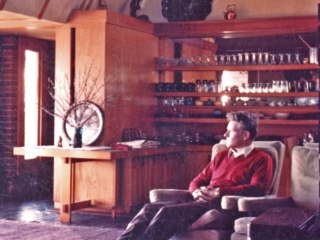

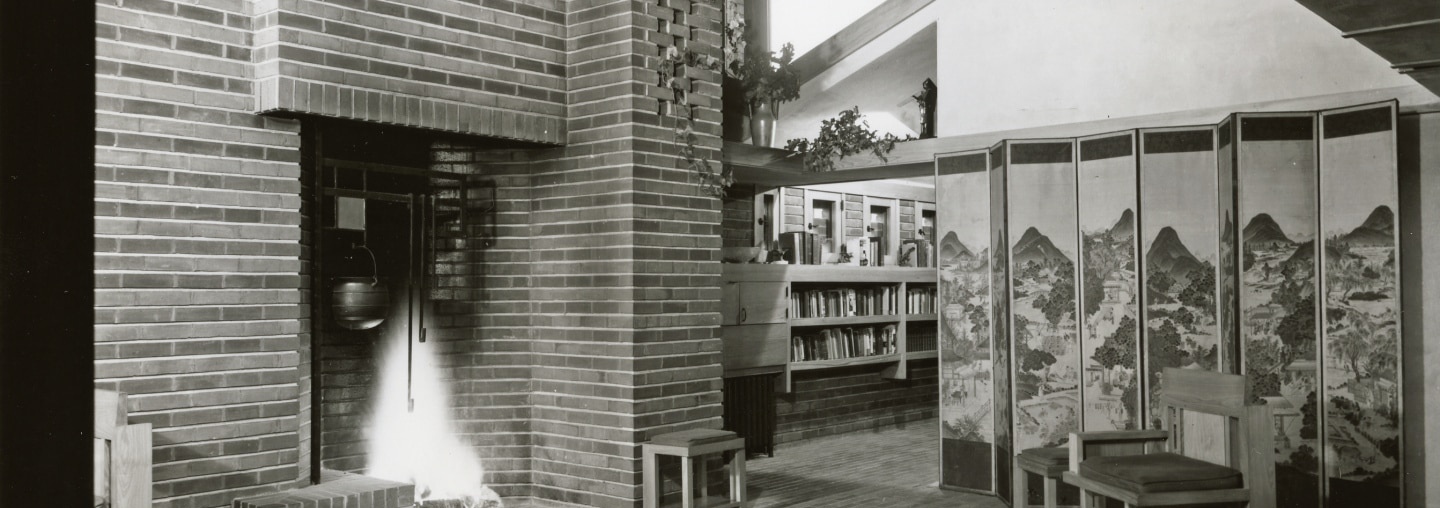

A fleeting moment in time, depicting the early years of the Willey House is well preserved in the acclaimed, January 1938 Architectural Forum, an issue dedicated entirely to, written by, and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship. In this landmark issue of the Forum, rendered in stunning black and white photography, the Willey House interior was revealed to the world. Carefully staged, lit, and turned out like a debutant, it is done up with a large, oriental folding screen that runs the length of the east wall of the living room. The same portfolio of photos illustrating this and other Wright buildings, made by the Chicago firm of Ken Hedrich and Henry Blessing were repurposed in various publications over the years, most notably in Frank Lloyd Wright’s own, “The Natural House,” 1954, where Willey is the first residence featured. Reminiscent of Taliesin where such screens are integrated into the fabric of the great house, this exotic piece of centuries old, Asian art is displayed as a befitting aspect of the room, as comfortable as any other furnishing gracing the space.

From the first, I was possessed with that glorious, multi-panel screen commanding the room. I needed to know what had become of it. Was it on loan from a University of Minnesota collection? Had the Willeys actually owned it themselves? If so, where would it have gone?

Photo courtesy of Chicago History Museum, Hedrich-Blessing Collection.

I can’t remember how, but in 2003 or 2004, submersed in research related to the Willey House restoration, I happened upon what appeared to be the identical screen online. I found it in the collection of a Milwaukee institution. Amidst the urgent demands of restoration research, and now, with any hope of recovering the screen for the house pegged at zero, I failed to record my discovery, and over the years lost track of it altogether.

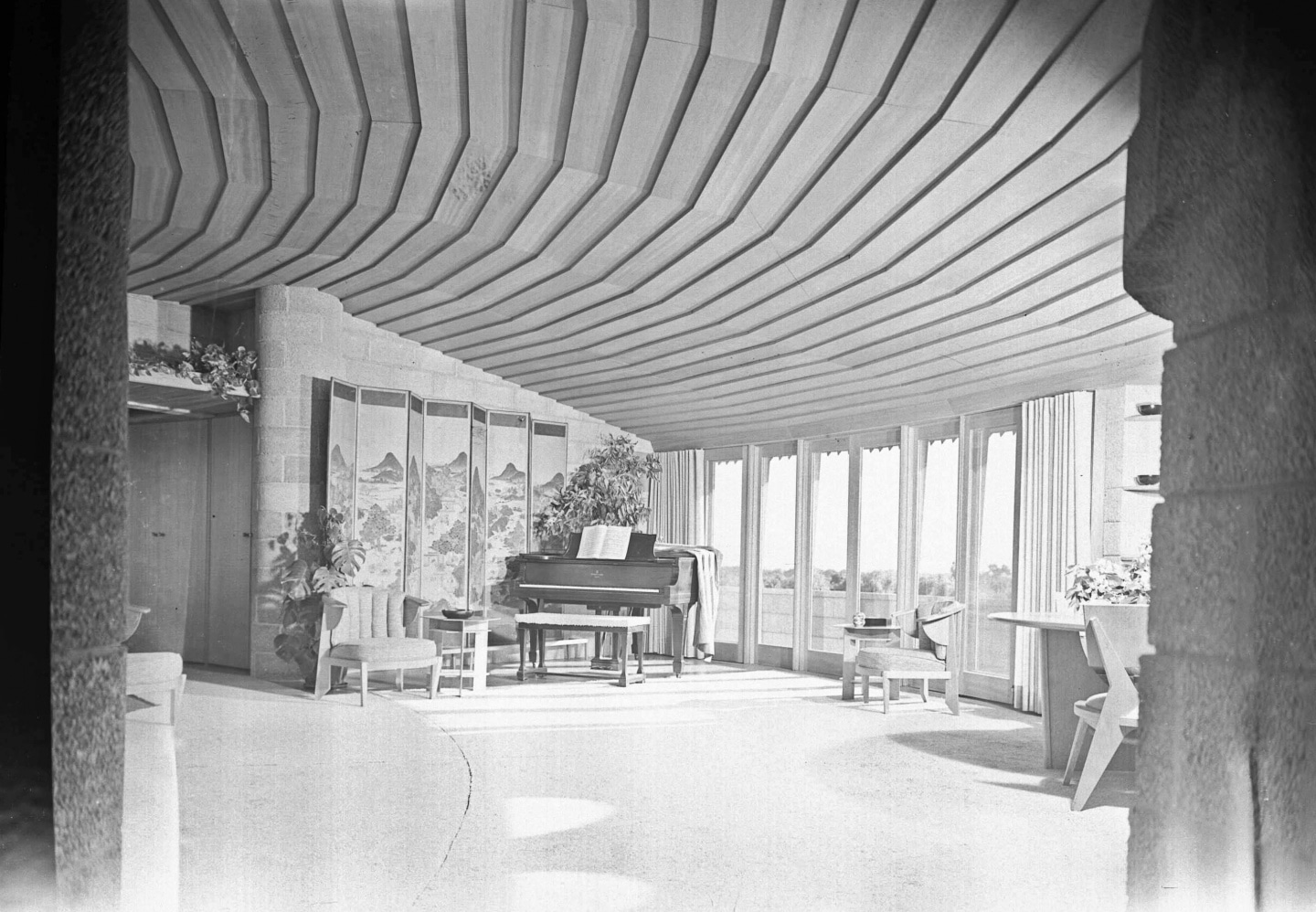

Sometime later, I noticed the familiar patterns of this landscape in an unexpected place. That very same screen reappeared in photos of the David Wright House, featured in the October 1959 issue of House Beautiful magazine. Searching other publications from the era, featuring the David Wright house, there it was again in the June 1953, House + Home magazine article Frank Lloyd Wright: This New Desert House for His Son is a Magnificent Coil of Concrete Block.

David Wright living room from House Beautiful magazine 1955. Photo credit: David Wright residence, circa 1955, Maynard L. Parker, photographer. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California, photCL MLP 1588 (027), The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

How could that be? Did the screen belong to Frank Lloyd Wright? (Yes.) Did he use it to stage houses for photo shoots? (Sort of.) Or was there a link between the two houses or clients? (As it turns out, there was.)

In a March 26, 1936 letter from Nancy Willey to Frank Lloyd Wright she wrote: “Just a line to tell you what a delightful evening we had with your son, David Wright and his wife, Sunday evening. They loved the house and we were happy to have them in it.” David Wright appears in the correspondence again, later that same year. On this occasion, his father mentions him.

Dear Malcolm and Nancy Willey:

We are having our traditional Halloween party Saturday night, October 31st. we plan to have fun among ourselves and a few intimate friends – in other words, more of a family party. So please do come with costumes and masks, so that may we not recognize one another – for a few minutes or even hours, maybe!…

We will take care of you to stay as many days and nights as you will enjoy.

We wish you could come out with David Wright (we hope he can drive you) to whom we are sending an invitation. Communicate with him. Please let us know – do not disappoint us.

Sincerely yours,

FLLW

Mr. and Mrs. Frank Lloyd Wright

Taliesin: Spring Green: Wisconsin

October 2nd, 1936

To the:

Bloodgoods

Lloyd Wrights

John Wrights

Llewellyn Wrights

David Wrights

Willeys

Glassenburgs

Marian Creaser

Mrs. Thompson

Mrs. Wallace

Fritzes

John and Marybud

Mrs. Baer

Vada and Alden (Dow)

Kohlers

Phillipson

Lautners

Roberts

Helen and George

Masselinks

Ferdinand Schevill

This wonderful invitation, which they accepted, established that David and Gladys Wright were, at the very least, acquainted with the Willeys. Nearly one year later, in the fall of 1937, the Architectural Forum photo shoot was announced to the Willeys, more as a directive than a request, in a brief letter from Eugene Masselink:

MRS MALCOM WILLEY: 255 SOUTH BEDFORD STREET:

MINNEAPOLIS: MINNESOTA

Dear Mrs. Willey: You and Dean Willey will be glad to know that the Architectural Forum is publishing an entire issue in January on all the recent buildings by Mr. Wright: 76 pages in all. In this connection Kenneth Hedrich, photographer from Chicago, will be coming up to Minneapolis sometime this weekend to photograph your house. This is only by way of explanation when the young man presents himself.

Sincerely,

Eugene Masselink

TALIESIN: SPRING GREEN: WISCONSIN: October 19th, 1937

Two weeks later, Nancy reported back to Olgivanna. (Note: the Halloween party she was unable to make, was a second, 1937 party. The Willeys did attend the 1936 party with David Wright, who presumably chauffeured them.)

Dear Olgivanna,

Our weekend is just too crowded to be able to make the Hallow’een party. We do appreciate your asking us to join Taliesin in that jolly tradition.

We have been wanting to see you. May we come the following weekend? (Can reach Spring Green Friday evening leave Sunday evening)

Among other things I want to talk to Mr. Wright about a built in couch in the living room here. We have a scheme buzzing in our heads to set Malcolm up in a workshop (garage) and to make ourselves the cypress furniture.

Tuesday and Wednesday Kenneth Hedrich and Earl Gerlach were here with their amazing equipment. It was very interesting to watch them work. There was one moment when we had stripped the beds of five blankets for purposes of holding back the sun! We enjoyed meeting them and were delighted at the thought of a complete F.L.W. issue. I’m sure Hedrich’s work will be beautiful. The negatives of Taliesin made us homesick.

Our best wishes to you, always.

Sincerely,

Nancy Willey

10-30-37

Asian screen, in the David Wright living room, early 1950s, matching the one displayed in the 1937 Willey House photos. Photo courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives.

Nancy makes no mention of a borrowed artwork in her letter to Olgivanna, however, in a February 1996 video interview, conducted by John Clouse and Lief Anderson, Nancy Willey revealed the secret behind the screen. The piece was loaned for the photo session by David Wright, and the Willeys were able to keep it in their house for a full season.

It seems Malcolm and Nancy remained friendly with David and Gladys. Because in her 1995 Oral History Program interview with Indira Berndtson, Nancy recalled visiting the David Wright house during a trip to Taliesin West, “I did visit a circular building he did for one of his sons, and picked a grapefruit from the tree in that place. I loved it…I don’t remember it distinctly – just that I was thrilled at the idea of it. The location was lovely.”

So, in review, David Wright owned the oriental screen that appears in the classic, 1937 photos of the Willey House living room and loaned it for the purpose of the photo shoot. But how did David acquire it?

I soon came across another clue. In John Lloyd Wright’s book “My Father Who is on Earth” he told a story about a bronze, Japanese Han vase his father gave to him. In actuality, it was left behind at the Oak Park Home and Studio, when the house became a rental. John found it in a rubbish heap in the stable and rescued it. Later, his father saw the bronze when visiting John and declared “Oh ho, so here it is!” And wanted to take it home with him. John relented saying if not for him it would be in the ash can. On each subsequent visit Wright moved the cumbersome Han vase closer to the door but it was too heavy for him to take. John goes on to say, “The following Christmas, dad sent each one of his children an oriental screen. That is, each one but me. He sent me a note: ‘Since you already have the Han, let it be your Merry Christmas present this year from Dad.” The relevant part of this amusing tale is this. Though John was short-changed, each of the other children, including David, received the gift of a Korean screen that unspecified year from their father.

Visitors we host on tour at the Willey House frequently arrive troubled by the fact that Wright abandoned his family, when he abruptly decamped for Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney. Not to suggest in any way that this was not painful for all involved, such loss and public shaming, but every indication was that Wright’s children, and quite possibly even wife Catherine forgave him for his mid-life crisis.

By his own account, Wright’s departure was as much an escape from the monotony of the Prairie house as from the constraining bonds of marriage and family. “My Father Who is on Earth” was not a book written by someone who resented his father in any way. John was perfectly capable of isolating Wright’s foibles, eccentricities and even petulance from his true character. The children, at least those who went on record, loved their flawed and charismatic father.

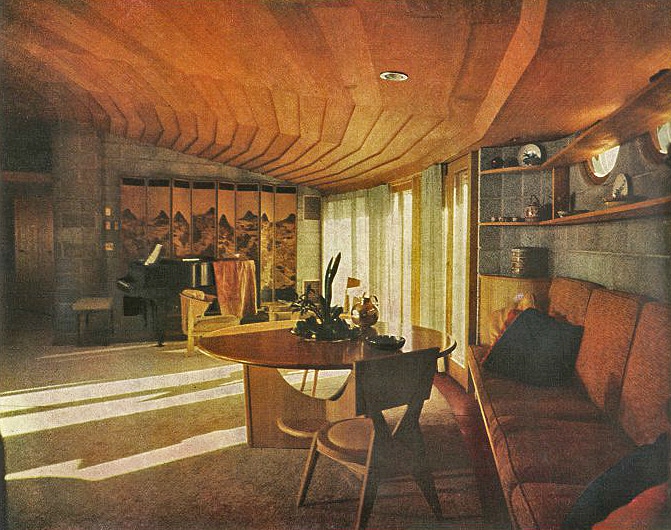

David Wright living room, used in House + Home, June 1953. Photo by Pedro E. Guerrero, © 2019 Estate of Pedro E Guerrero.

John’s chapter entitled “What We Appreciate We Own” seems to explain how the screen fell into David Wright’s hands. Now, where did I say that screen was? For a coupe of years I attempted casually to locate the Milwaukee repository for what I now suspected now to be a Korean screen, and gift from father to son.

My online collection searches were all in vain. I attempted to contact the Milwaukee Art Museum to inquire as to whether the screen might be in their collection and could never elicit a response. Recently, I reached out to friends in Milwaukee for some much-needed assistance. Surely someone on the local scene must know a curator or patron of the arts familiar with Asian collections in Milwaukee, right?

Wright homeowner, Nick Hayes, owner of the ASB Elizabeth Murphy House offered to check with a contact at MAM. Simultaneously, Mike Lilek, of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Burnham Block Inc. graciously offered his own help and advice. He reminded me that Milwaukee had other museums, and that possibly the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) was a place to look. Their focus was more on natural history, but their collection was broad and vast.

I reached out to the curator of anthropology collections at MPM. My email bounced back with a notification that she’d be out of town for more than a month. My heart sank a little. Another delay. But then, one day later I received another message stating that my inquiry was forwarded to the History Department, where Asian culture materials are found. I learned that the Asian screen was indeed in the Milwaukee Public Museum collection. It is catalog number N18558/22543. The record stated that it was purchased for the Museum by a “friends” organization. The screen was described in the catalog as an 8-fold screen, landscape of Korea. From Al Muchka, Curator of Collections, American & Local History, I learned that the screen was, and is currently on exhibit in the Asian gallery (third floor), in the Korean house unit of the MPM. Beyond that, no further information was available. He sent a snap shot to confirm the match.

Found it! I responded to Mr. Muchka with the background I had discovered behind the piece, and asked for more detailed physical information on the screen. He sent back a response saying that he’d add the background to the file, and suggested we’d come as far as we could. But, he had asked a museum librarian/archivist to check into the director’s correspondence and quarterly reports for any shred of evidence that might exist. Perhaps she might unearth some reference to the piece.

I wasn’t particularly optimistic that anything more would be gained, but was delighted the screen had been located and positively identified. You’re probably wondering, okay, so where’s the plot twist? Well, it wasn’t long in coming. I heard back again from Mr. Muchka, when just a few hours later, he sent a third email. The excited curator told me “I could call him Al.” He had just come across something astonishing while searching the department records. He discovered that catalog number N18658 did not correlate with the Asian screen depicted in the photos I sent after all. Instead, the screen in question was catalog number N23626/24225. It was indeed a 1976 gift, directly from David Wright. There had been confusion in the official museum documentation.

At this point I became deeply infatuated with Al. The screen, has continuously been on display in the Milwaukee Public Museum’s Korean House exhibit at least since 1988. Over time, the screen, somehow become dissociated from its historical record. Once the correct identification was made, the rest of the story gracefully unfolded. The record confirms all earlier suspicions.

In 1975, David Wright put the screen up for sale on the open market, with no immediate buyer. In that same year, he visited this Milwaukee Public Museum and saw what was then, the new Korean House exhibit unit. After a meeting with Director, Dr. Kenn Starr, a specialist in Asian archaeology and culture, and a bit of further correspondence, Wright agreed to donate the screen directly to the Museum to complete the display unit.

The screen is of painted silk applied to paper backed panels. It is 6 feet tall by 10 feet long overall. Each panel is approximately 14 inches wide x 72 inches high. The screen is identified as “Scenes of a Korean countryside.” It dates to the 18th century (circa 1750). The background setting is of rivers and mountains, bridges, walking peasants and scholars. Specific subject matter illuminates scenes of agriculture and of textiles making. The panels focus on rice or wheat cultivation and fruit orchards, with a second focus on spinning, weaving, and dying of textiles. The piece was repaired sometime in the late 19th century, and again for David Wright in 1972. The artist’s name is unknown and unattributed. But in his donation, David Wright declared that the artwork was acquired by his father, Frank Lloyd Wright, in 1912, while visiting Seoul, Korea.

Scenes of a Korean countryside, circa 1750, Gift of David and Gladys Wright. Image Copyright Milwaukee Public Museum #N23626.

After decades on permanent display, the museum had no official photo of the screen until now. Mr. Muchka assured me that the screen is very handsome and pictures hardly do it justice. I believe him.

Sarah Levi, David’s granddaughter, was able to confirm, through her mother, the loan of the screen to the Willeys. She also explained the reason for the donation to the Milwaukee Public Museum. Frank Lloyd Wright gave son David another Asian screen, slightly smaller in stature. That second screen was easier to display on a wall.

It was impossible to predict the turn of events that led to discovery of the whereabouts of the mysterious Asian screen in those 1937 photos.

Although I am still pining over the screen in place in the Willey living room, I understand that it never really belonged there. I am happy to know where it resides now and delighted that this line of inquiry helped to re-establish a connection between artwork and provenance for the Milwaukee Public Museum. The fact that this Korean screen was owned by two members of the Wright family, and also appeared prominently in pivotal images of the elder Wright’s architecture, only adds to the mystique of the piece. I can only hope this arcane discovery will have opened a portal, creating a new destination for Wright fans when visiting the city of Milwaukee. Now I too, must make the trip, to see it at last, for myself.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan

Part 9: Hucksters, Charlatans, and Petty Criminals

Part 10: Lo on the Horizon

Part 11: Origins of Wright’s Cherokee Red

Part 12: One Thousand Words

Part 13: The Plow that Broke the Plains