Architect gives new life to Frank Lloyd Wright’s demolished and unbuilt work

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | May 2, 2017

Spanish architect David Romero talks about his thought process behind creating photorealistic computer renderings of unbuilt or demolished Frank Lloyd Wright buildings.

DISCOVER MORE OF ROMERO’S RENDERINGS OF THE UNBUILT

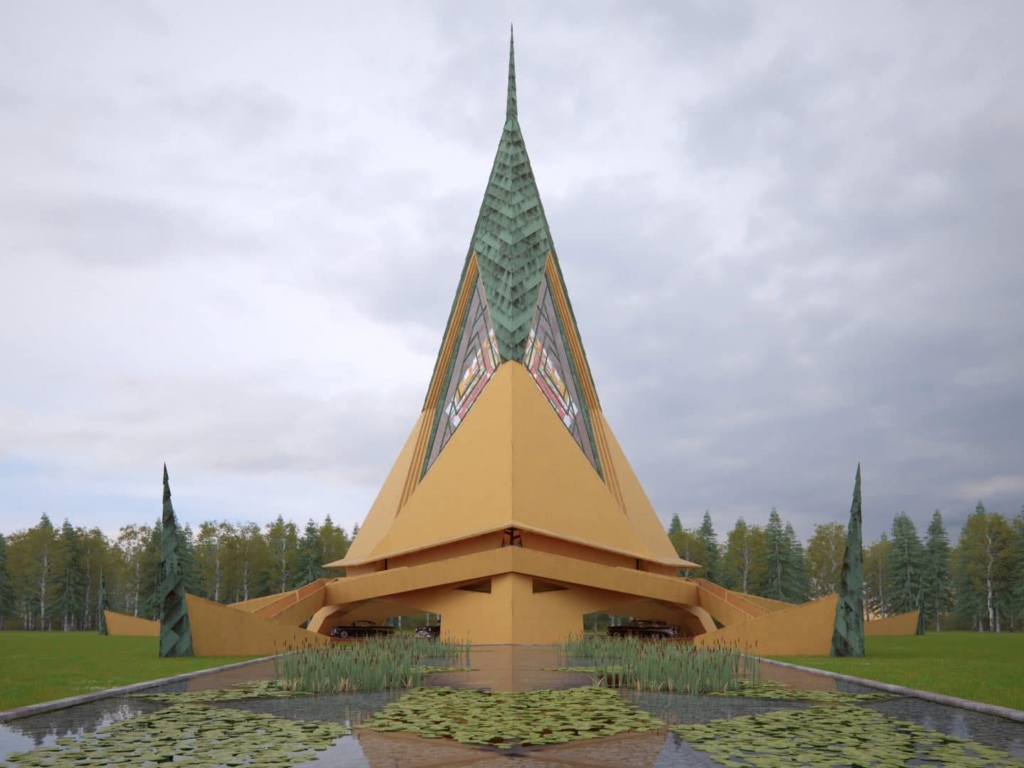

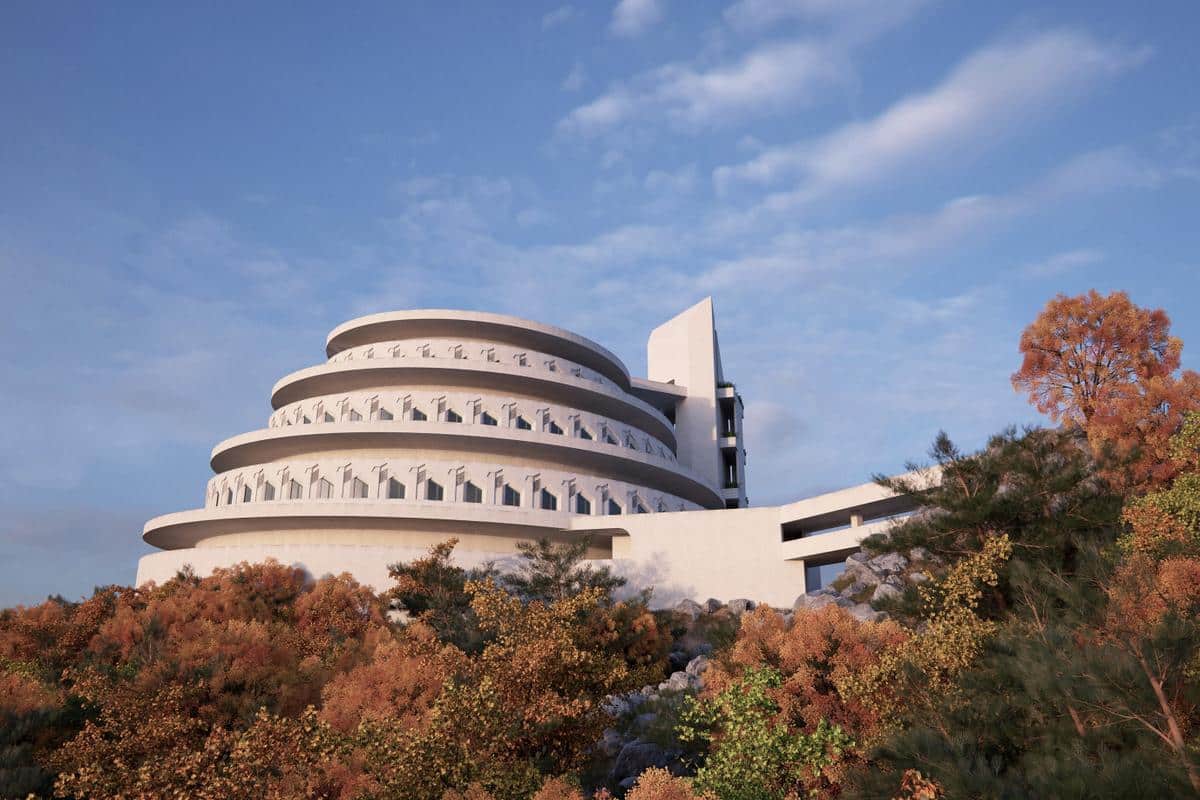

For the upcoming issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine, focusing on Wright’s unbuilt projects designed for automobile use, Romero created a series of renderings of the unbuilt Gordon Strong automobile objective, a tourist attraction designed by Wright in 1924 to sit atop Maryland’s Sugarloaf Mountain.

David Romero’s “Hooked On The Past” was driven by his two loves: the history of architecture and the world of computer generated images. The research-heavy personal project led him to recreate the unbuilt or demolished structures by Frank Lloyd Wright, the architect whose work he believes is the most exciting of the 20th century.

We asked Romero to tell us more about how these computer renderings were created, the difficulties of recreating Wright’s work, and the reactions to his images.

What inspired you to create images of Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs?

David Romero: My project “Hooked On The Past” was born from the union of two of my hobbies: the history of architecture and the world of computer generated images. In the first context, Frank Lloyd Wright is of course a key figure and in a very particular way his work is, for me, the most exciting of the 20th century.

From the beginning it was a personal project of research and learning, with both advanced techniques of 3D representation and specific works of architecture. So, I decided that they had to be works that did not exist, either because they disappeared or because they never came to be built and the reason is simple: 3D rendering tools serve precisely for this, to show what does not exist.

Can you describe the process of creating these images?

DR: I start the model in Autocad (a bit dated, but I’m still learning Revit), then I export it to 3ds Max + Vray where I add textures, lights and cameras, as well as vegetation and the environment. Finally there is some retouching in Adobe Photoshop, although very light.

Soon I hope to add on my website a detailed description of how I have done the projects of the Larkin Building and the Pauson House, which I think will be interesting for those familiar with these types of tools.

How did you choose which Wright designs to create?

DR: I try to choose buildings that are relevant within his trajectory as an architect, but Wright was so prolific that only that criterion would leave us many buildings to choose. After that, I simply choose work that I like. Finishing each model on the images that can be seen takes several months of work in my free time, so it is important to enjoy the process.

What are the unique challenges of approaching Wright’s designs, as opposed to another architect or designer?

DR: The complexity in the ornamentation makes their designs very difficult to model, as well as the fact that almost all the furniture was designed specifically for each work. These require much more time than, for example, modeling a building designed by a minimalist, such as those of Mies van der Roe.

Fortunately, 3D rendering techniques have come a long way and there are plugins for 3ds Max, like Railclone, which make it much easier the task to generate complex ornaments in buildings.

There is great deal of discussion about your images of Wright’s designs, how does this affect your work?

DR: In my experience the only thing that can annoy a fan of Wright’s work is when the recreations are not faithful enough to the original. As soon as I made public my recreations, the first thing I did was to show them where I knew I could find some constructive criticism. The chat on savewright.org is a great place to discuss this topic as is frequented by all kinds of fans and connoisseurs of Wright´s work. Since I am the first interested to finish my work as exact as possible, I have patiently changed all those inaccuracies that anyone has pointed out to me. But I think the reactions have been very positive and people value the result a as a contribution to Wright’s legacy.

On the other hand, it is true that there is some controversy, which may have some connection with my work, about physically rebuilding Wright’s disappeared works and in that debate there are opinions of all kinds. Here again I think the greatest fear is what would happen if the reconstruction is not faithfully enough to the original building, although personally I would love to see the Larkin or the Pauson house physically rebuilt.

Can you explain some of this feedback?

DR: In terms of feedback, I found this article to be the most interesting.

The author focused on this controversy over physical reconstruction, although at one point he pointed out that since my work is so realistic, it could somehow replace the need to build the buildings physically.

It is obvious that the experience of an image can never replace the sensory richness of visiting a building physically, but who knows, perhaps virtual reality will advance to that point someday.

Virtual recreation, with its limitations, also has certain advantages over real recreation as it does not have to comply with current regulations. For example, in the Trinity Chapel Wright designed beautiful access ramps with a single constant slope throughout its path. This design, perfectly valid in 1958, would not meet today the requirements of the ADA code and the design would lose the elegance of its simplicity.

In any case it is strange to me that someone is in favor of a virtual reconstruction and not in favor of a real one, when in my opinion the only important question is if the work is well done. There are many successful cases of physical recreations of great quality that attract thousands of visitors such as recreations of the Brancusi Studio or the Barcelona Pavilion.

And going back to virtual reality, I’m working on a dive in the Larkin building through this technique. I think it’s going to be something awesome that will delight all Wright fans.

What do you hope people will experience when viewing your images of Wright’s designs?

DR: From the beginning my work tries to be the most similar to what would happen if we had a time machine and we could visit those buildings as they really were in their time of greatest splendor. During the process of developing the models, it is very exciting for me when I start to see those images that show those works of art that no one has seen in more than sixty years. I sincerely hope that all the fans of Wright’s work can feel that emotion too.