Willey House Stories: The Space Within: Part 5, “The Purpose”

Steve Sikora | Mar 30, 2021

The Space Within – Part 5: The Purpose “… the sense of materials and the purpose of the whole structure in this dwelling.” -Frank Lloyd Wright, The Natural House Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s own description of the Willey House, in this, the fifth and final part of the Willey House blog series The Space […]

The Space Within – Part 5: The Purpose

“… the sense of materials and the purpose of the whole structure in this dwelling.”

-Frank Lloyd Wright, The Natural House

Inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright’s own description of the Willey House, in this, the fifth and final part of the Willey House blog series The Space Within, we’ll explore the concepts of:

- Acoustical properties

- The freedom and shelter paradox

- The Garden

- Something eternal

Acoustical Properties

Wright’ organic architecture is an architecture of time, place and people. Invariably, his working palette was a curation of indigenous, natural materials; such as native stone (local earthen clay brick in the case of Willey), unfinished or lightly finished, resilient woods, plaster, concrete and glass. In Wright’s masterful hands and considered use, earthen materials offer a combination of reflective, resonant and sound absorptive qualities. Wright, sensitive to aural properties of wood, stone and glass, to some degree “tuned” his buildings as if he were a luthier crafting the body of a musical instrument, through his inspired specifications and intuitive shaping of the void. Overall, his interior spaces tend to be sonically pleasing places to linger in. In the case of the Willey House the living room acoustics are ideal for conversation and music. The brick floor and glazed surfaces yield a sound quality brighter than in the sleeping quarters, where the absence of brick renders those spaces audibly dampened, absorptive and ultimately restful.

No photo of the highly photogenic Grand Canyon can prepare a first time visitor for the absolute silence standing at the edge of the void. Photo by Jeff Goodman

Like most people, I will never forget that first moment I stood at the edge of the Grand Canyon. Like everybody else I came prepared for a visual feast. What was unexpected, and to become my most lasting impression, was the absolute dead silence that I experienced facing into that yawning, mile deep chasm. With nothing for sound to reflect off of, the Grand Canyon was as mute as deep space. This was a surprise field study in acoustics. Despite anticipation of the sweeping visual, it was the sound, or lack of it, I remembered most. I had the opposite auditory experience when I attended a party held at a highly celebrated, modernist prefab house. I’d been in the house once before for a photo shoot. The house was quiet then and so were we.

However, sharing the largely glass and concrete space with 200 boisterous celebrants and a blaring sound system was an acoustic atrocity of nightmarish proportions. Apparently a modernist glass box makes the perfect echo chamber, perfectly fine if you don’t mind living inside of a drum. But unless mitigated by carpets, draperies and overstuffed furniture, modern boxes can be as acoustically unlivable as Wright suggested all along.

We must consider the role materials play in Wright’s constructions, since they are critical to the overall sensory experience of inhabiting his spaces. The visceral attractions of Wright’s predominantly earth-born materials, are lost on no one who enters. The organic nature of his material specifications prove a grounding counterpoint to his advanced spatial manipulations. His palettes, wildly variable as they are, bring us into closer communion with the natural world while serving up a sumptuous feast for the senses. The gorgeous textures and tactility they impart, beg to be caressed, much to the chagrin of tour guides and homeowners alike. The fragrance of natural materials as they transmogrify under changing climactic conditions communicate the season and weather. A whiff of wood smoke pervading the home thanks to the ever-present central fireplace, imparts a deeply primal sense of comfort and belonging.

In the ell where house and garden wall meet, Wright carved out a small plot for cultivation of a garden. Photo by Steve Sikora

Though we are visually oriented creatures, who react primarily to what we see, it is the underlying earthen scents, the surface qualities ranging from rough-hewn to polished and especially the satisfying acoustics of his natural materials that help set Wright’s spaces apart as distinctly different, inherently appealing and truly livable spaces.

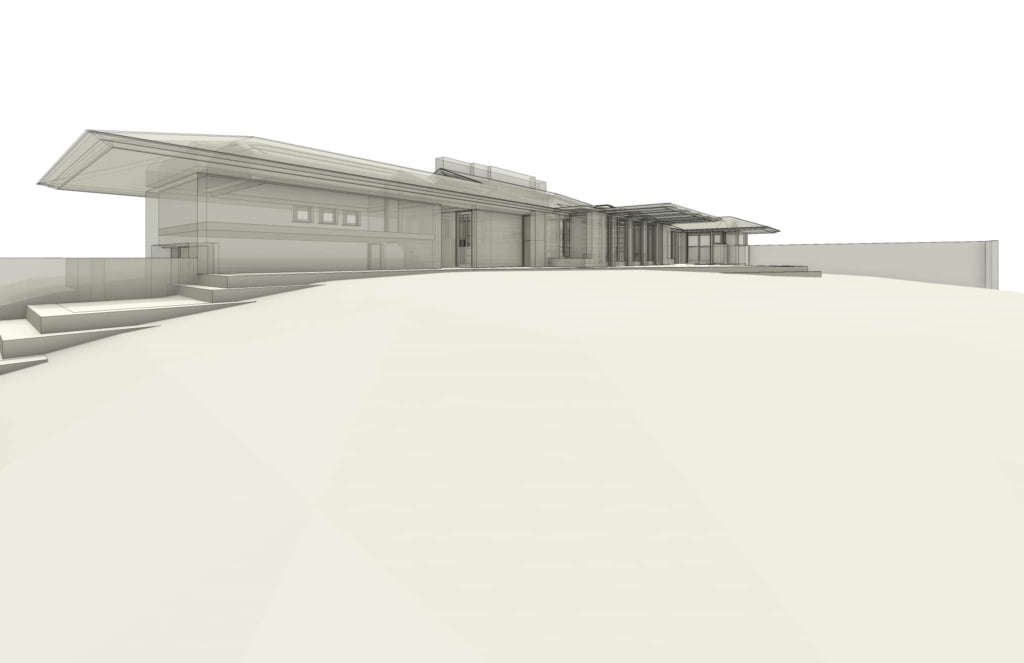

The Shelter as Freedom Paradox

The Willey House, as other Usonians, is essentially impenetrable from one side. Often the approach side of a Usonian home is cloaked in a wall of imposing, solid masonry; an unambiguous signal to the uninvited. In the case of Willey, the brick masonry is pressed into the slope on the north side, effectively turning its back to the Prospect Park neighborhood in a most un-welcoming fashion. On the opposite side of the house however, hangs a glass wall of French doors, that when swung wide, transform the house into an open-air pavilion. A curious effect when all the French doors on the south side are open is that the dominance of the partition walls seems to diminish. The effect is to create a low-ceilinged, even subterranean sense of shelter that is fully exposed to the landscape in glorious Panavision all across the facade, fully embracing the outdoors and even blurring the distinction where edifice ends and nature begins. This implicit sense of security summoned by the solid masonry is what triggers the sensation of unconstrained liberty, freedom and pure abandon on the exposed side of the house. The ideals of Democracy Wright expressed are clearly demonstrated in the physical.

Perfectly elucidated in his lyrics for the song Free as a Bird, John Lennon cites the causal relationship between security and freedom, the very same sensations that Wright evokes in his architecture for the Willey House.

Free as a bird

It’s the nearest thing to be

free as a bird

Home, home and dry

Like a homing bird I’ll fly

as a bird on wing

– Free as a Bird by John Lennon, 1977 (home demo, take 1)

These seemingly contradictory ideas of freedom and shelter are not antithetical, but rather contrapuntal. Wright often spoke of architecture in musical analogies. In music, counterpoint is a combination of two or more independent melodies juxtaposed into a single harmonic texture. The interplay of their essential oppositions generates a polyphonic richness of complex emotion. The idea is similar to a string that must be tethered to the earth in order to allow a kite to soar. The comforts of shelter, home and dry, are the nearest thing to feeling free as a bird.

The Garden

Wright became a master of the manipulation of interior space, but there is another sort of void Wright sought to fill with his architecture. This one, he recognized in the soul of man. It is that ineffable vacuity that has caused mankind, since time immemorial, to continually quest after some form of reunion with Mother Nature.

As scientific understanding has grown, so our world has become dehumanized. Man feels himself isolated in the cosmos, because he is no longer involved in nature and has lost his emotional “unconscious identity” with natural phenomena … Thunder is no longer the voice of an angry god, nor is lightning his avenging missile. No river contains a spirit, no tree is the life principle of a man, no snake, the embodiment of wisdom, no mountain cave the home of a great demon. No voice now speaks to man from the stones, plants, and animals, nor does he speak to them believing they can hear. His contact with nature has gone, and with it has gone the profound emotional energy that this symbolic connection supplied.

-Carl G. Jung, Man and His Symbols

The terrace outside Wright’s bedroom opens itself to the immediate plantings of trees and flowers, but its most potent draw is the vista overlooking the whole the Taliesin estate. Photo by Steve Sikora

Every generation hungers in its own way for a return to natural ways. Often this deep-seated yearning is paired with a sense of man’s arrogant overreach, industry run amok or climate urgency. Today we have Greta Thunberg as a lightning rod for the global climate crisis confronting us. Before her Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth provided sparks of inspiration. Preceding Gore was Greenpeace. For my generation, it was Woodstock, Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, and The Mother Earth News. A half-generation before those things existed, Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac and Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring sounded environmental alarms and spurred a reevaluation of our relationship with the environment. These sources all inspired back-to-the land movements of sorts. As did publication of Helen and Scott Nearing‘s Living the Good Life in 1954. Half-century prior to that, Frank Lloyd Wright’s childhood was spent sheltering under the influence of the Lloyd Jones side of his family tree.

The God-Almighty Joneses like other immigrant pioneers, out of necessity, lived solely off what the land could grant them. As a consequence they found it a place of spiritual solace that not only provided for basic corporeal needs, but inspired gratitude and a deep reverence for nature. No hollow platitudes, like those recited zombie-like, from a Sunday morning missal, needed to reassure them that all things earthly and spiritually emanated from nature, because for them, that was their day-to-day reality. The family quoted from the back-to-the-earth Transcendentalists, as often as from heavenly scripture. Wright, who was imprinted from an early age, peppered his own writings, not to mention the walls of the Taliesins, with the wisdom of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman. The importance of living in proximity to the earth was central to Wright’s worldview, so quite naturally, his personal beliefs would extend themselves into his practice.

Frank Lloyd Wright said he “believed in God but spelled it Nature with a capital N.” His ideas about man’s interrelationship with nature flow from the wisdom of the Transcendentalists. Chiefly among them was Emerson who wrote:

Let man, then, learn the revelation of all nature and all thought to his heart; this, namely; that the Highest dwells with him; that the sources of nature are in his own mind, if the sentiment of duty is there.

– The Over-Soul

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Not only are God and nature intertwined like a ball of twisted yarns, but a coming to terms with it, can only occur within the individual.

Biophilia is a word that describes humankind’s innate biological desire to seek communion with other life forms and the earth itself. As civilization flourished and spread, humans were relegated to life indoors, and authentic connections to the natural world became harder and harder to make. So much so that today a longing for a meaningful reintegration with nature is a universal phenomenon. In some religious traditions metaphorically, this sense of deprivation can be described as a yearning to return to the mythical Garden of Eden, man’s lost and perfect state of grace in God and in nature. Theologians seeking the locus of the paradise on earth, from which Adam and Eve were expelled, place The Garden in a region where the Tigris and Euphrates rivers flow. But in fact, The Garden may not be geographically specific at all.

If we put aside religious dogma and consider the Garden of Eden only as a paradisiacal state where man once dwelt in total harmony with nature, the idea has archeological roots that can be traced. In Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari identifies several “revolutions’ in the development of the modern species. Approximately 70,000 years ago the behaviors of Sapiens changed dramatically. In a short period of time, they (we) inexplicably spread from Africa into Europe and East Asia, crossed oceans, suddenly invented tools, sewing and clothing, and created art. “Most researchers believe that these unprecedented accomplishments were the product of a revolution in Sapiens’ cognitive abilities.” This Harari calls the “Cognitive Revolution,” a paradigm shift that gave Sapiens an intellectual advantage over competitors, and allowed them to gain domination over other species and their environment. Another milestone was achieved roughly 10,000 years ago. This time, Sapiens, who for 2.5 million years existed as hunter-gatherers, no so different from any other wild-eating animals roaming the planet, shifted paradigms from following their food seasonally, to raising it locally for their sustenance. This deviation in behavior caused historically nomadic humans to become sedentary. Because of this shift, the “Agricultural Revolution” as it was dubbed also marked the beginnings of civilization. To remain in place required the development of elaborate support systems to make immobility a sustainable proposition. Depending on how one chooses to define the moment, somewhere between 10,000 and 70,000 years ago, self-aware Sapiens began identifying as separate from nature, no longer subject to predation or the vagaries of natural cycles. It was in fact Sapiens reason, cunning and technological developments that drove mankind from The Garden, not an angry God. And it seems we’ve carried that remorse in our DNA ever since.

We are stardust

We are golden

And we’ve got to get ourselves

Back to the garden

– Woodstock by Joni Mitchell

© Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

It is not surprising that Wright’s places of worship were also devised to help rejoin man with nature. Archbishop Iakovos recognized the significance of Frank Lloyd Wright’s connection between his heavenly architecture and the earth. At the dedication of the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church he acknowledged the virtues of Wright’s plantings at the church comparing them with Eden, “In the gardens here you can meet and meditate and learn from flowers. They have much to teach us. This thought came to my mind—God first created a garden.”

-The Roots of Life, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright

In Nancy Willey’s photo album a picture entitled “Our View 1937” shows how the house embraced the span of the southern horizon as much as it did the immediate yard. Willey House Archives

What inspired my research for The Space Within was the sweeping appeal that the Willey House holds for visitors. Curious as to understanding why, from the outset it seemed obvious that it was more than Frank Lloyd Wright’s bewildering and sublime aesthetic that touched people so deeply that they did not want to leave after the tour. The spell that overcame them was not cast by any superficial aesthetic, but by something else, something far below the surface.

Something Eternal

At a Taliesin West event commemorating 150th anniversary of FLW’s birth, Lorraine Etchell, a student in the Master’s Program at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture stood to deliver a few words. She had studied architecture in San Francisco and upon graduating, felt disenchanted, as if something was lacking from her education. She found herself questioning whether she even wanted to pursue a career in the field. Until she happened upon the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, a subject not taught in school. Her discovery of his work and philosophies whacked her worldview off its axis. During her brief comments, she said a remarkable thing. She described Wright as being “more than simply modern.” She said his work was “eternal.” A follow up email, months later helped confirm the profundity of what I thought may have been an involuntary expression of deeper truth. Lorraine told me “It is a challenge to describe what I’ve come to know about the intangible nature of Taliesin. And in just the short amount of time between that event and now I have grasped so much more… Taliesin and those who live it are in continuous a state of becoming… part of this ‘eternal’ I spoke of.”

Coincidentally Nancy Willey used exactly the same word “eternal,” when she described the act of receiving guests at the house:

“The more conventional way of entertaining was indoors, lined up on a buffet table. (but) My favorite was a breakfast party…people streaming in and out of doors, enjoying the house. (They served daiquiris croissants and avocado with lime.) The house was wonderfully helpful in entertaining. People somehow to themselves felt something bigger than their small gossips…in nature…having a good time in a relaxed way. They were participating in something “eternal” so to speak…I don’t think they were aware of this consciously.”

-Nancy Willey Interview Video 1-4, (Chapter 4)

The house impressed guests with the sense they were part of something far greater than a gathering of friends and associates eating brunch.

Olgivanna Lloyd Wright put it this way:

The presence of Mr. Wright’s spirit is manifest in his vibrant thoughts. These thoughts have their wavelengths—they generate power in others. The waves of these thoughts will never cease to exist; they are imperishable. And of course the higher the mind rises, the more powerful are the thoughts. The power of Mr. Wright’s thoughts will carry on into the infinite future.

–The Shining Brow: Frank Lloyd Wright, Olgivanna Lloyd Wright (Pg 294)

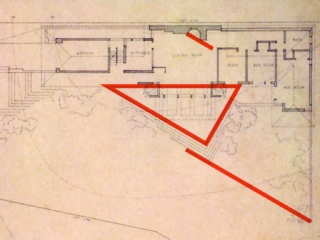

By constraining visibility and physical access to the lot from the north and east sides, Wright created a private enclave for the Willeys. It extended the privacy and security of their home into the garden and far beyond into the greater landscape. Modeled by Craig Beddow

Greater than Frank Lloyd Wright’s personal “love of work,” his architecture was actually “invested with love,” with spirit, with that metaphysical quality that is so hard to put a finger on, because it is so rarely seen today.

Though addressed obliquely in his later writings, it’s unlikely that Wright ever discussed the perceived mystical aspects of his houses with clients. Just as he did not point out the complex underlying geometries that helped make their small homes surreptitiously spacious and desirable places to dwell. To be fair, a magician is never compelled to reveal how those doves got into his coat, or how he knew you held the Ace of Spades because the power of the trick relies on it remaining a secret. Beyond keeping his secrets, it is clear Wright thoughtfully contoured his house designs to the particular needs and personalities of his clients, once he knew and understood them. But like any talented designer, he omitted pointing out certain intangible aspects of his conceptions that might confuse clients or that qualified as a level above what they really needed to know or simply might not understand. Hidden layers of craft, artistry and meaning are routinely engineered into design. Those layers exist for the sole purpose of testing a creator’s own abilities and pushing the work into higher realms.

For instance, Nancy Willey was not a gardener. She didn’t even want to grow a lawn (Wright suggested clover instead.) No embodiment of garden; formal, casual or native existed on the site of her home when she and Malcolm purchased the lot. She didn’t specifically request a place to nurture vegetables, though a carefree indoor/outdoor lifestyle was highly appealing to her. Still, Wright carved out for her a private niche at the junction where house and wall intersect, to sequester a small plot for cultivation of unspecified plants. Various flowers were grown there over time but it never developed into anything that could be construed as a planned garden per se. Instead, the real benefit of her remarkable new house, and one Nancy did fully appreciate was the opening of the bank of operable glass doors to the outside, creating the effect of an expansive open pavilion. While this effectively conjoined the little garden plot with the living spaces, more notable was the connection to the entire landscape, up to and including the southern horizon. So I need to ask, what “garden” was Wright referring to when he named the house?

In a series of letters posted between July and August of 1934, Nancy Willey and Frank Lloyd Wright discussed a cornerstone for her house, then under construction. The cornerstone was intended to be hollowed-out so as to contain a few artifacts and photos, a sort of time capsule. It was going to read “Architect Frank Lloyd Wright” following the name given to the house. Wright proposed “The Garden Wall,” a designation that left Nancy a cold. She said that she wished for something to represent the “pioneering spirit” of the house and countered with “Prairie House.” Predictably this too familiar appellation represented a former style Wright would have viewed as her house superseding. He failed to respond, and their inability to agree on a name probably derailed the cornerstone altogether.

Likewise, the term The Garden Wall never did catch on in the way, equally descriptive names like, Fallingwater, Deertrack or Stillbend did, though the architect continued to use it. There may be another way of looking at Wright’s intended meaning. Grounded in the understanding that for half a century Wright’s perpetual objective was to restore his clients to a complete harmony with nature, by opening the living spaces of their homes to native landscape, perhaps a more profound depth of meaning can be attributed to the name he insisted upon. Perhaps The Garden Wall, beyond describing the architecture, instead restated his original objective of reconnecting man (or in this case woman) to The Garden that humanity has for so long desired a return to?

Did you miss any of the “Space Within” blogs for this special 5-part Willey House feature? Read all five installments of the series:

- Part 1: Little Boxes

- Part 2: Vista Inside and Out

- Part 3: Sense of Shelter

- Part 4: Sense of Space

- Part 5: The Purpose