Willey House Stories Part 7 – Step Right Up

Steve Sikora | Jul 27, 2018

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

Header image: Willey House street view and entrance stairs. Photo by Steve Sikora.

Anyone who has ever visited the Willey House, seen it in photos, or simply passed by, is left with an impression of what must surely be its signature feature, a dramatic cascading staircase. The terraced steps rush like a river issuing from the front door and expanding gradually, as it descends and meanders down to street level. The brick stairway is an aspect of the extensive exterior masonry plan, a continuity of the interior living space of the small house, extending well beyond its walled boundaries, and contributing significantly to its monolithic whole. When one thinks of Fallingwater it is the array of floating terraces projecting into space that come to mind, at the Robie House, the long streamlined form of an ocean liner plying dry land, the Ennis House stands like a Meso-American castillo perched on a high prominence overlooking Hollywood, the lasting impression of the Willey House is its grand cascading staircase, disproportionate to the stature of the home. But Frank Lloyd Wright may not have felt the same way most of us do.

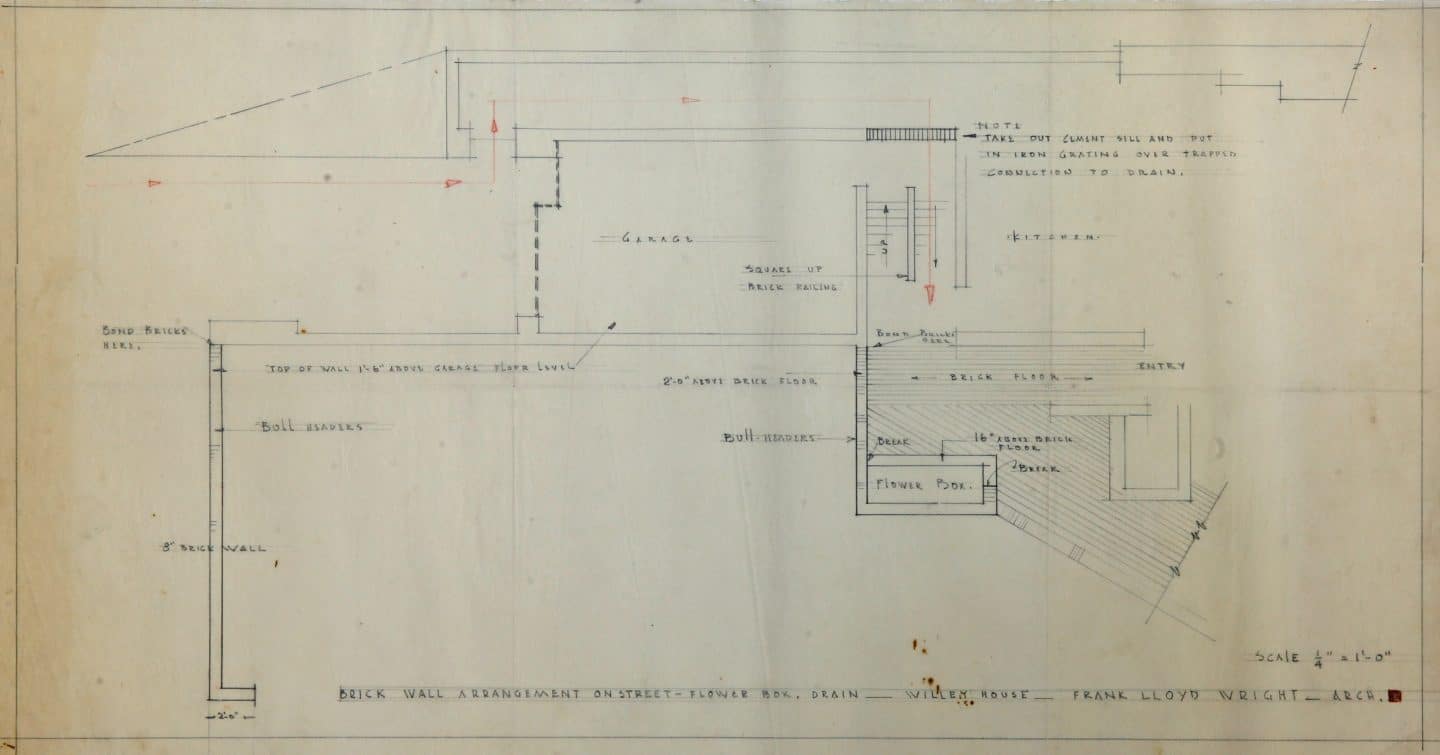

Years after the completion of the Willey House restoration, a delivery arrived at my door. I had anticipated its arrival. It was a USPS mailing tube sent from Lon Arbegust of the A.D. German Warehouse Conservancy. The contents of the tube were anything but expected. Just a week earlier, in a phone conversation with Lon, he told me that some Willey House blueprints had fallen into his hands and he wanted to do the right thing with them. Though research for the restoration was over, I explained that we were intent on assembling as comprehensive an archive as possible of all things related to the house, those who built it and those who have lived there in order to further our understanding of the house. Wondering if I was familiar with the prints, I asked if he could describe them. How did the text read? His descriptions sounded familiar. A drawing labeled “Reflected Ceiling Plan of Marking Strips”. Yes, I’d seen that. “Garage Floor Detail”. Sure. I thought knew what that was, and a third drawing that he could not quite explain. It was entitled “Brick Wall Arrangement on Street – Flower Box, Drain,” whatever that meant. I thanked him and said I’d be honored to include them in the archive.

The drawings had belonged to Harvey Glanzer, the third owner of the Willey House and former proprietor of the A. D. German Warehouse in Richland Center, Wisconsin. He had generously passed on a great number of artifacts along with the house. But Harvey taunted me for years with the idea that he had some kind of renderings or blueprints related to the Willey House he meant to present to us. Whenever I’d ask about what exactly it was that he had, he’d pause for a beat, then in a voice raised in volume and pitch, as if I was hard of hearing or somewhat dim, “DRAW-INGS!” “DROWW-INGS!” he’d bark. I always figured I would find out what it all meant some day. Then Harvey passed on. His common-law wife, Beth Caulkins gathered together some of Harvey’s possessions from the Warehouse before his son, Eric arrived with dumpster to purge the place for a quick sale. She retained a pile of rescued items in a house she maintained nearby. This particular house, one of three she owned, happened to be across the street from the German Warehouse. She kept a couple of cats there, though she resided 40 miles away in Mineral Point.

Beth told Stafford Norris, my stepson and our restorer, that she was holding some of Harvey’s items for us. She even sent a letter to that effect. Nevertheless, the items were never passed on, and one day she was involved in a severe traffic accident while in transit between residences in Mineral Point and Richland Center. Sadly, Beth did not recover from her injuries. Just prior to her accident she enlisted our realtor, Russ Fierst to sell yet another house she owned, this one in Minneapolis not far from the Willey House. Russ asked Stafford to help him clean out the place and do whatever was necessary to get it into saleable condition. The house was not yet ready for the market at time of Beth’s untimely death. Her nephew drove to Minneapolis from St Louis. He was executor of Beth’s will. He collected the items he considered to be the value from the house and discarded the rest. He apparently did the same at her homes in Mineral Point and Richland Center. We inquired about the cache of papers and artifacts Beth had reserved for us. His only response was that none of us were in Beth’s will and that was that. Shortly thereafter, it became clear that he had sold individual pieces to local antique dealers. One particular Willey House blueprint was offered to me through a network of dealers. I knew from the photos it had belonged to Harvey, and later to Beth. It had been folded several times and it was easy to identify from a tape of B-Roll video footage made by John Clouse in 1995 and 96. The blueprint eventually showed up on eBay, at a price far exceeding what I was willing to pay. Despite my best efforts I failed to recover a single one of Harvey’s “DROWW-INGS!” and I was pretty disappointed at my failure.

On the day I opened that mailing tube I was dumbfounded. Rolled inside were three, pencil drawings on tissue, each crudely but effectively encapsulated in plastic. A reflected ceiling plan for the bedroom wing of the Willey House (I had only seen the plan for the living room), a detail sheet for the brick and gravel garage floor, and a third drawing that was hard to comprehend, none of these drawings had I’d ever seen before. They did not exist in any archive. Each was a hand-drawn original.

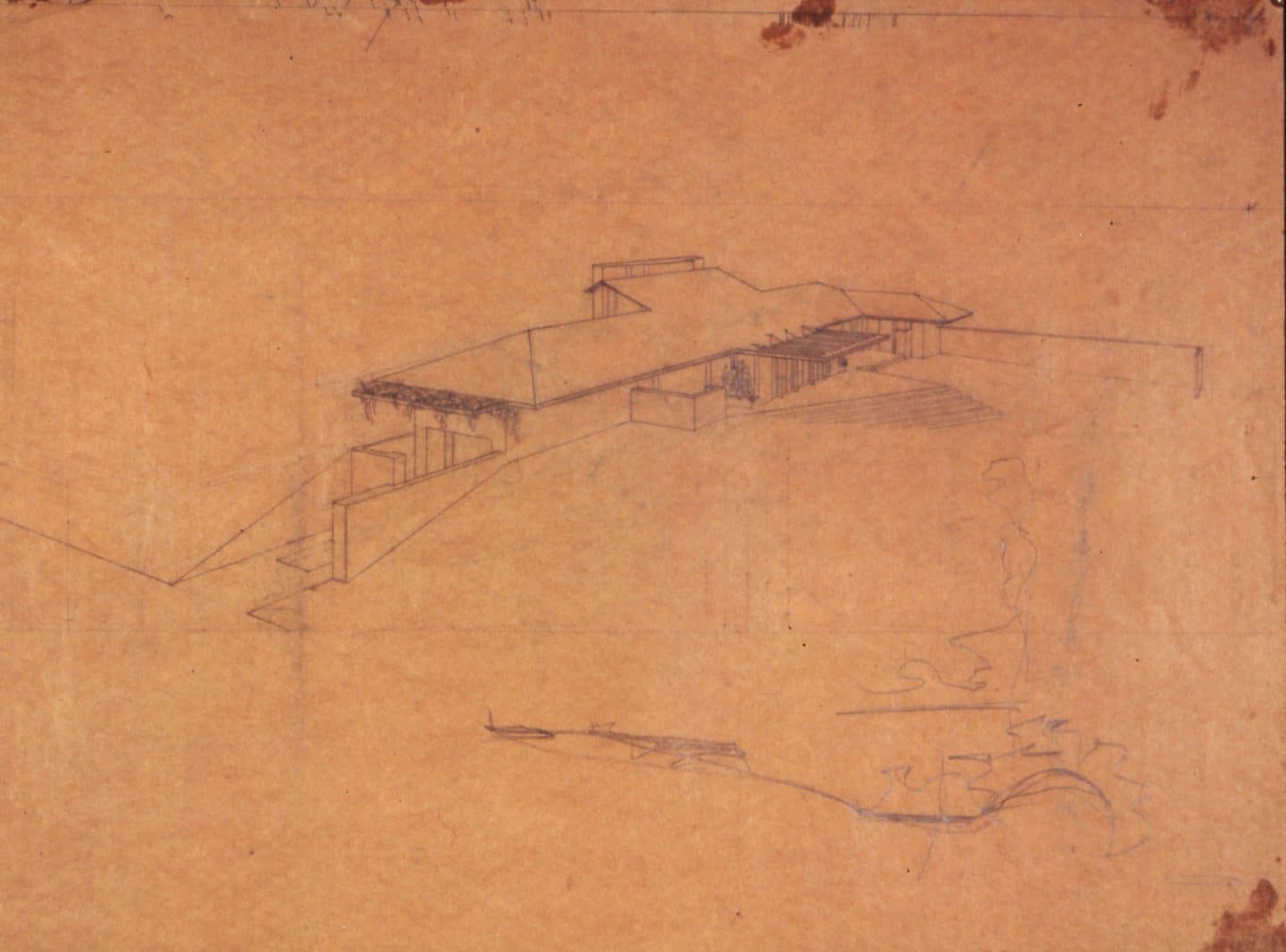

Aerial perspective showing revised entry. Trellis added above garage door.

Wright’s alternate entry plan for the Willey House. Photo courtesy of the Willey House Archives.

The third and most puzzling of the three captivated me. In plans I’ve seen, Wright would sometimes combine a plan and elevation on a single sheet that could create a temporary spatial disorientation in the viewer, but that was not what was happening here. I could not grasp what I was looking at, but for a different reason. I showed the sheet to Lynette who immediately said “Well, that’s the plan of the street end of the Willey House. See, here is the garage and the driveway, and the edge of the terrace, but there are no steps.” No steps? No steps! No wonder I didn’t understand what I was looking at. Without the context of the staircase I simply could not orient myself. I literally could not “un-see” the staircase! I showed the drawing to Stafford and he had the same challenge grasping what was before him. We resisted seeing what those drafted lines were clearly telling us, simply because the Willey House without a stairway was unthinkable!

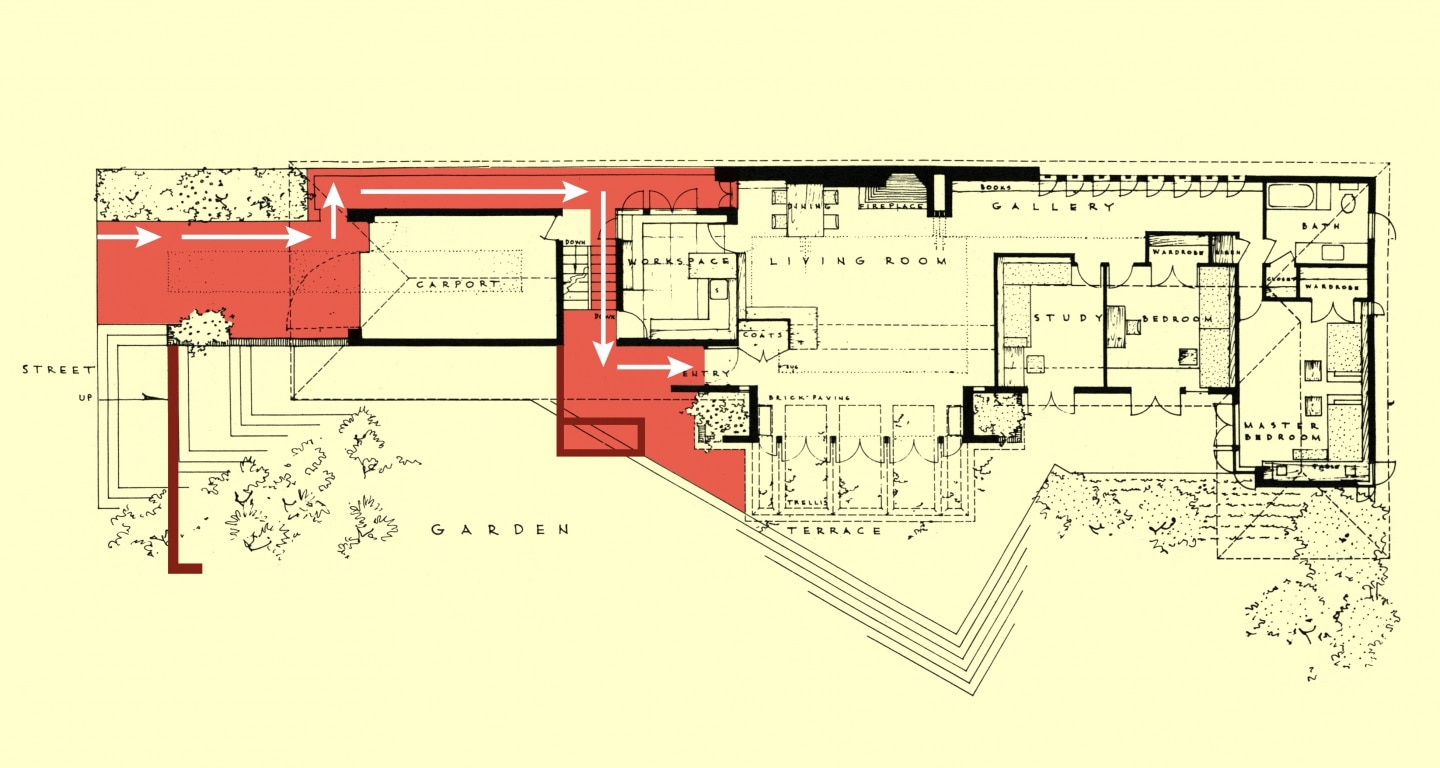

I believe the drawing was made in Wright’s hand. The lettering perfectly matched that used in another drawing in our archive, embellished with a note to Nancy Willey, from Wright. In place of the cascading staircase was an earthen slope. On the street end of the plan there is a low, masonry curb that holds back the hill, where the bottom step would have been. A tall planter box is placed to obscure a direct view of the front door. And in red pencil, an entry procession is drawn, directing a path up the driveway, left and up two steps, right along the passageway north of the garage, right and up another flight of steps, then left to the front door. A perfectly Wrightian entry sequence, but utterly contrary to the original approach, which is directly up the stairs, where a compression began upon reaching the top landing. Why the reconsideration? What drove the making of this study? Why was it retained by the Willeys? How is it that did no one else seemed to know of its existence?

Returning to the Willey House drawing set, in the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, there it was, hiding in plain sight. Two perspective drawings numbered 3401.003 and 3401.005, the first drawn on manila and the second on butcher’s paper. I had always assumed them to be early and incomplete studies because of some additional variations in the house. Suddenly they answered the question of what was happening in the confusing drawing I had just received. They were not early studies at all. They were alternate entry plans that showed the house without the iconic staircase! I suddenly saw the perspective studies in a strange new light and now, at last understood their significance.

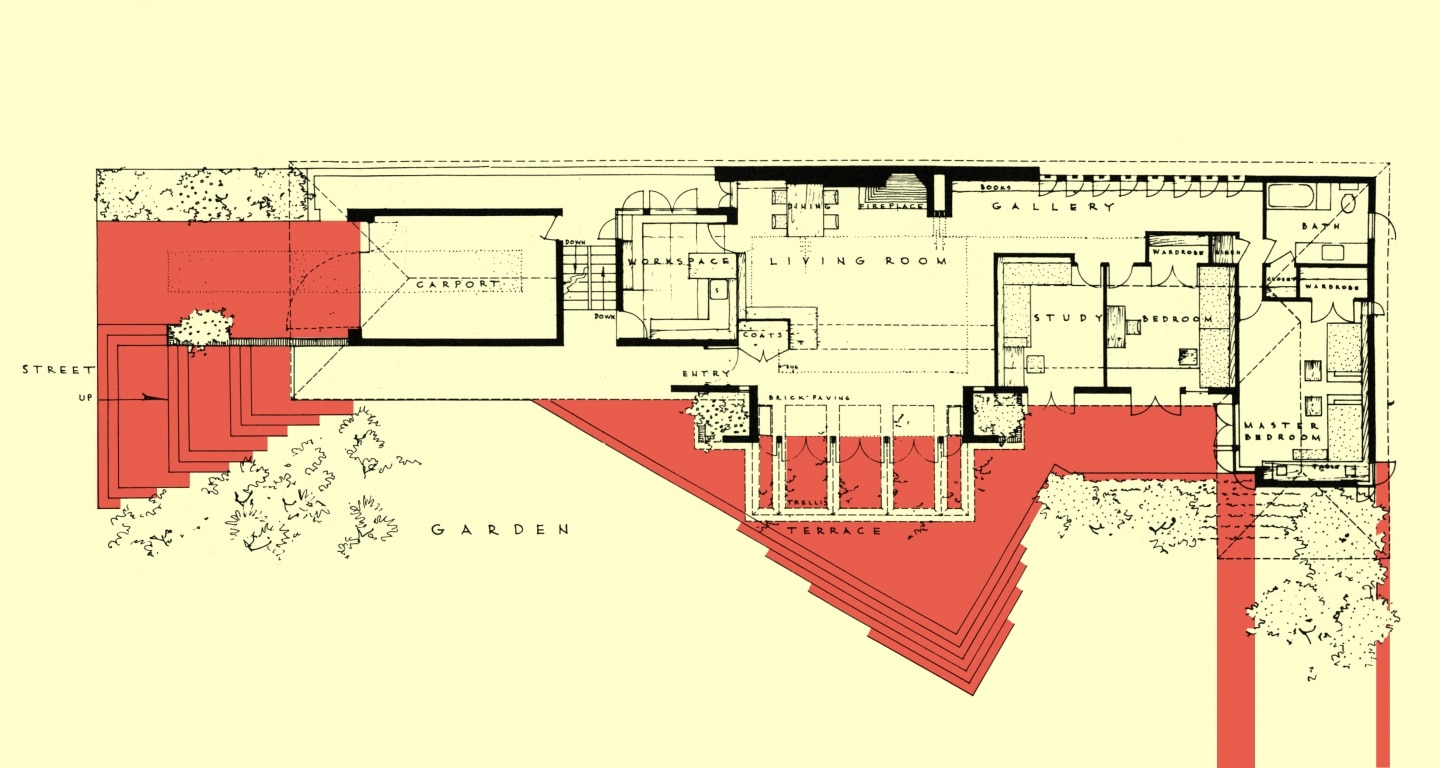

As-built masonry plan. Red highlights areas show areas incomplete in the fall of 1934.

Alternate entry plan, highlighted in red, shown superimposed over as-built plan.

The omission of the stairway is consistent with the cloaked entries indicative of many Usonian houses that turn their backs to the street in favor of creating open and flowing private spaces for their inhabitants. Could it be that Wright’s thinking was shifting while the Willey House was under construction? We’d seen his submission of late detail changes before in the correspondence. Perhaps he wanted to create greater privacy? Malcolm and Nancy like other owners of the house, faced intense scrutiny from their neighbors as well as the curious onlookers who came to see this strange new home for themselves. Might Nancy have asked about creating a less inviting street presentation, due to the unwanted attentions of strangers? Or was it something else altogether?

In late November of 1934, when Nancy and Malcolm moved in, the exterior masonry was left incomplete. Postponed were the stairway, terraces and the garden wall. The intent was to finalize these details when the weather was again suitable in the spring. Wright was deeply concerned about the garden wall in particular. He asked if bonding bricks had been placed in to the bedroom wing in order to connect the garden wall to the house. He pleaded with Nancy in a handwritten note, “Dear Nancy Willey is there no way to build the rear wall before the mason gets away? Brick changes. No two masons do work just alike and there is likely to be a difference between old and new. Besides the whole is badly out of balance without the wall.” His concerns seemed overwrought, except for the fact that Nancy had already been hinting that they were approaching the end of their budget. On October 26, she wrote “Dear Mr. Wright, I’m not sure yet whether we can have any outside brick work at all or not, but I shall know soon.” Nancy proposed truncating the length of the wall. “In raising this question there is one thing very much on my mind and that is I am greedy about the distance and being able to look off into the distance, and lovely as the wall is for the background of a garden, I resent anything that cuts off the far off spaces.” She made sketches of the wall stepping down as it ran downhill to the south. She also had concerns about its overall height depending on the final grading of the yard. “…I love the idea of the garden snuggling down under a high wall. But to take the sharp slope without stepping the wall down would make the wall outrageously high.” To achieve the grade Wright proposed for the flight of steps off the terrace would have made the wall 13 feet tall at its southern end. “The consideration of cost is also outrageously high…” “Please consider seriously if anything can be done; at present it is very expensive and very high.”

Wright responded in late October. “The wall should not be expensive. Why not get another estimate on the wall. Perhaps they are adding up “losses” and putting them into their estimate. I sincerely hope for the wall uncut even if the Willeys make a floating debt on the installment plan. The wall will stay if the debt does “float”.

The clients were running low on resources. It is no secret to an architect, that despite best intentions, when a homeowner says they will complete something at a later date, it seldom comes to pass. It is now clear that this potential for blindness to the incomplete, the possibility of procrastination and the very real financial limits of the clients concerned Wright enough that he began looking at a Plan B.

No conversation regarding an alternate entry procession is documented in the correspondence. But clearly conversations occurred, and a plan was submitted to Nancy, or it would never have been handed down with the house. The fact that such a profound change does not get any ink, tells me that the Willeys promptly assuaged Wright’s fears of sacrificing the garden wall, for which the house was named, avoiding the unthinkable. It shows us that when confronted with an impossible choice, Wright was able to prioritize, and refocus on what mattered most to him, and that was not the obvious feature we see and recall today in the completed work.

In a eureka moment, looking back through the collected correspondence exchanged between fall of 1934 and spring of 1935, I discovered a passing reference. In a letter from Edgar Tafel dated December 26, 1934, he wrote, “Enclosed are the drawings for the Ottoman and the rearrangement of the entrance, the later of course for use at some later date when all this frost is well gone.” There it was, waving at me like a plastic bag stuck to a cactus, plain as day. The reference confirms precisely when the alternate entry plan was drawn. Coincidentally, the other drawing that Taffel mentions, a plan for an ottoman, was also retained by Nancy, and resides in our archive as well. In a letter to Gene Masselink in April of 1934 Nancy states, “As for the outside brickwork, which I hope we will be starting soon, we can’t bear not to put in the broad steps in front as originally planned; the whole is so beautiful.”

My inability to comprehend the relatively simple plan view of the Willey House sans steps, remains a profound lesson for me. As foolish as I feel for my obvious blindness, it is imperative that I confess it, for what I learned from this moment of self-examination. My obliviousness to plain fact is a metaphor for the political situation we find ourselves in today as citizens of the United States. Individually, we seem incapable of seeing any viewpoint that we don’t already believe to be true. Add to that the confusion caused by the barrage of intentional fallacies, both great and small masquerading as truth we are confronted with daily. All of this serves as a reminder to me, when researching the Willey House to make every effort to verify facts, even those in print, or especially those in print. Because personal beliefs can and do influence our perceptions of reality. Misinformation, once spread is difficult to correct later. Frank Lloyd Wright himself was not beyond changing the dates on drawings to suit his preferred narrative. For example, I noticed recently in the authoritative Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph 5, published by A. D. A, Edita, the Lusk and Hoult Houses are both dated 1936, the same year as Jacobs 1, when in fact, they both preceded Jacobs by a year. Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer’s text does call Lusk “the first Usonian design in his text”, (later corrected that to Hoult), but by back dating the projects to be concurrent with Jacobs 1, it conveniently prevented them from interfering with Wright’s declaration that the Jacobs House was “Usonia One.” It is but a reminder that the old adage “trust but verify” is valid, particularly in the specious domain of Wright mythology.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers