Willey House Stories Part 5 – The Best of Clients

Steve Sikora | May 4, 2018

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

Any designer will tell you that clients, even prized ones, don’t always know what they want, much less what they actually need. Sorting it out is exactly why a designer’s empathic and independent perspective plays such a crucial role in the success of a design.

Eames Demetrios offered valuable insight in his book The Eames Primer. In it he identified a construct that his grandparents Charles and Ray Eames recognized and put into practice. They called it the Guest/Host Relationship. It was a principle that grew out of conversations with peer, Eero Saarinen, became core to their design process and contributed immeasurably to the Eameses success as multi-disciplinary designers. Their practice of employing empathy to help identify the best solutions to human problems was so fruitful in fact, that half a century later, many of those Eamesian solutions still resonate. The premise was simple; “the role of the architect, or the designer, is that of a very good, thoughtful host, whose energy goes into trying to anticipate the needs of his guests “…We decided that this was an essential ingredient in the design of a building or a useful object.” A good designer must play the role of a gracious host not that of a controlling egotist. Frank Lloyd Wright was more than capable of inhabiting both roles. Publicly, he cultivated a reputation for egocentricity or “honest arrogance” as he preferred to call it, but privately, Wright had the best of intentions for his clients and those intentions are clearly translated into his highly personalized buildings. The Willey/Taliesin correspondence provides ample evidence of his patience and magnanimity for the young couple. Although hardly a prerequisite in business, I believe this architect and these particular clients developed a true and lasting friendship. The benefit to Wright was a significant, creative breakthrough late in life. The Willey’s reward, was fulfillment of their dreams, the opportunity to be among the first to experience mid-century patterns of living in their new home, an environment befitting their personalities, social status and aspirations, and as it turns out, those of a new generation.

The designer and client are dancers in a complicated tango of wills. My partner, Lynette and I shared the mixed blessing of leading a design and branding firm for over 30 years. One of the lessons you take from that, is the understanding that the quality of your work is significantly determined by the quality of the clients you work with. Notice, I said work with, rather than work for. When a designer is able to ally as equal partner with a client of vision and courage, it creates fertile ground for optimal results in every endeavor. Doubtless, in our practice, our greatest achievements would not have been, were it not for the engagement, faith and occasional challenges presented by our clients. In the case of the Willey House, Nancy presented Wright with enough constructive resistance to lift her dance partner above the prevailing paradigms of domestic architecture.

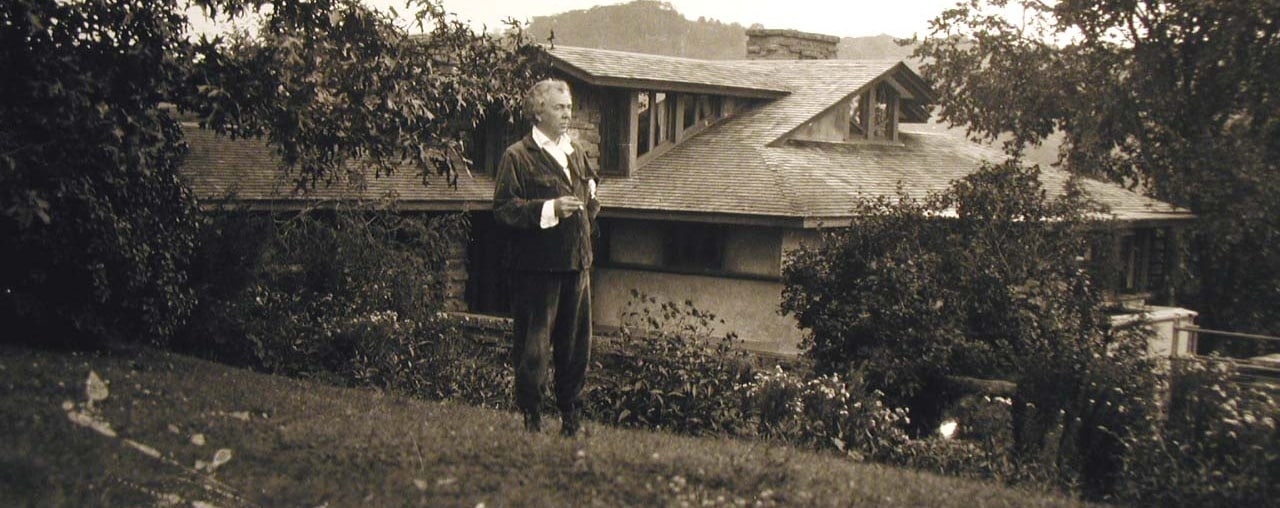

Frank Lloyd Wright, age 65.

When John Lloyd Wright considered a career in architecture, his father gave him this advice, “You’ve got to have guts to be an architect! People will come to you and tell you what they want, and you will have to give them what they need.” “Don’t you take the wants of the client into consideration?” John asked. “If you consider the house first, you will supply the needs of the client. The wants change from day to day, but a house must embody the needs of those who live in it. The architect must be aware of those needs, the client seldom is. An architect must have the courage to turn away a commission even if he is hungry if his work will not represent the highest ideals….Think it over, John: to be an architect is no light matter.”

Though there is no single approach to designing something, aspects of the process are inherently similar across disciplines. The creation of an identity, or the design of a useful tool or device, design of a website, design of a decorative object like a vase, or design of a utilitarian object such as a chair, the process is one of cyclical development, repeated trial and error. An idea is researched, considered, sketched, prototyped, tested and refined through an iterative series of incremental improvements before it is ready for market. It is not unusual for a designer to feel the stress of inadequate time for iteration, because with each revision, new opportunities for improvement are revealed. Charles Eames had a ready quote for this situation, “ The best you can do between now and Tuesday is still a kind of best you can do.” Without a doubt, deadlines and budgets do inspire results. In fact, the deadline is often the first subject of conversation with a client. It defines scope, budget and expectations in a commission. A defined endpoint is a requisite for any design to see the light of day. But for the Eames office, the process of product design iteration continues long after an item has gone into production. The relationship they forged with Herman Miller has far outlived Charles and Ray. If refinements to a product will make it more sustainable, or better suited to current conditions without sacrifice to integrity, the Eames family will consider it. Better is always better, just as it was with Charles and Ray. Wright’s own Wisconsin home Taliesin is an example of living architecture subject to constant dynamic change — improvement, experimentation and evolution. But most architecture, including that of Wright’s clients, is only executed once.

Malcolm Willey with dog Charlie. Photo from Nancy Willey’s photo album.

The practice of architecture during Wright’s lifetime, offered dramatically fewer opportunities for testing and incremental refinements than did other arenas of design. In his 1931 lecture, To the Young Man in Architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright famously said, “The physician can bury his mistakes,—but the architect can only advise his client to plant vines.” To avoid the obvious consequences of ill-conceived invention and to create greater efficiency, much in the field of architecture has been standardized to vast catalogs of modular componentry, applied in a manner to satisfy a prescribed standard building code. However, in his innovative, hand-made buildings, what Wright substituted for architectural standardization or conversely, the tools of product design; focus groups, product testing and prototyping were two simple things; a targeted audience of one person, and the implicit trust of his client, in short, the stuff of human relationships. Nothing else was available to him and nothing else required. As John Sergeant observed, “The relationship between client and architect was for Wright a thing of joint intent.” To achieve clear focus and gain permission, even “In large projects he always sought out one person and never a committee, to represent the client.” That, as they say, is easier said than done, but it was a prerequisite that governed his creative and persuasive processes.

Design aficionados and practitioners alike are subject to the adulation of shallow illusion. A higher definition of design is short sheeted when appreciation fails to look beyond mere surface treatment or the allure of polish. Good design is not a purely aesthetic exercise, it is not defined by current trends or fashion, virtuosity, or shock value, although those things can and do contribute. Good design must always be concerned with satisfying a human need. Purpose should remain primary. What good is a daring or photogenic building that is unlivable? Architecture is the expression of the human, built environment. It must serve human needs to qualify as good design. Wright was a showman, but he built with clear purpose and integrity.

Consider this, a client will typically select an architect based upon their past artistic expressions. Nancy Willey was certainly a case in point. Yet the same client will judge their architect by how well their needs are met, once the design is implemented. This too, is evident in the correspondence between Nancy Willey and Frank Lloyd Wright. In her initial letter she asked “What do you think are the chances of my being able to have a – creation of art?” She repeatedly expressed wanting to follow his instructions to the letter. But when pressed into a corner, having to decide between high art and pragmatism, she was willing to fight for what she knew she needed and could afford. On November 17, 1933 frustrated with construction bids coming in at two times over budget on scheme 1, she penned a terse letter to Wright. In it she wrote, “I do not want a seventeen thousand dollar house even at twelve or ten thousand dollars. I want an eight to ten thousand dollar house at eight to ten thousand dollars. Can I have it?” We have Nancy’s red line and assertive pushback to thank, for what inspired Wright to cast aside his initial ideas and ultimately seek a more appropriate solution. Once the water broke, something new and wonderful was born, relieving the tension between clients and architect. From that point forward, in full alignment, both parties strove to advance the project with renewed enthusiasm. In Nancy’s own words from her Oral History interview with Indira Berndtson “…and how he responded, once he accepted it!!

I had the chance to meet a life-long graphic design hero of mine, Milton Glaser. It was at a conference in New Orleans, where we both presented. An idea from his presentation became indelibly inscribed into my memory. While discussing his long career, Milton spoke about clients. He said, “I could never work for anyone who I did not have a genuine affection for.” His words were profound, because they implied two things; he could only do his best work for people he liked, but also, in a professional context, he gave permission for designers to understand, appreciate and embrace clients as fellow humans, even potential friends. He believed in collapsing formal, professional barriers. I instantly related his sentiment to my own client relationships.

For most of Frank Lloyd Wright’s clients, building with him was the highlight of their lives. Like other clients, Nancy Willey was perfectly enthralled with the man. The extent of her enchantment is hinted at in a curious letter written from a Rochester, Minnesota hotel, during the winter of 1938, while she was a patient at the Mayo Clinic. “During the first week I wanted to write you and tell you how cheering and splendid a thing your portrait is, when one is away from home, in a hotel room. I have four or five of them around the room and they make me feel I’m not so far from home. But since Malcolm brought down the Architectural Forum, last night, the joy of discovering Time is outdone by the glory of the Forum…I love the words you gave us, (There is no doubt you did it,) and I bow to my title, and feel delightfully rewarded.” The January 1938 issue of the Architectural Forum, credits Nancy Willey as “Supervisor” in construction of the Willey House, a title he gave her and one she fully deserved.

Nancy Willey in her living room. Photo courtesy of Shawn Beckwith.

The Willeys and Wrights remained cherished friends, visiting each other and sending gifts for more than a decade after completion of the house. It is not surprising that additional furniture designs also continued to roll in years after the commission was initriated. In October of 1945, after a weekend at Taliesin, Olgivanna penned a note to Nancy, “It was so nice to have seen you and Mr. Willey. Frank and I decided all over again that you both are among our closest friends.” But the warm relationship between the Willeys and Frank Lloyd Wright was never more clearly evident than when Nancy and Malcolm at long last, moved in to their dream home, achieved through common purpose.

A Western Union Telegram sent on November 21, 1934 to Mr. Frank Lloyd Wright read: “MOVED IN YESTERDAY. YOU HAVE MADE ANOTHER MASTERPIECE. THRILLING BEYOND WORDS. GRATEFULLY. – NANCY AND MALCOLM WILLEY”

And in response: “HERE’S HAPPINESS TO THE BEST OF CLIENTS NO MASTERPIECE TOO GOOD FOR THEM. – TALIESIN”

Nancy Willey was a prototypical, modern woman, on a journey of self-discovery, breaking trail well ahead of her time. She was courageous, intelligent and curious. As a graduate of Barnard College Nancy believed she was destined to do important things in life, and she did. Contributing to a new domestic architecture was merely one of them, and it is uncertain she, or anyone else, realized the impact of her role, until decades later. Despite the paternalistic labeling of plans that read THE MALCOLM WILLEY HOUSE, there is no mistaking the fact, this was Nancy’s house through and through. Thanks to Nancy’s full engagement in every aspect of the planning and execution of the house she was able to freely interject fresh thinking, ripe for the cultural conditions of the moment. The austerity of the Depression, a desire for simplicity, the demise of rigid, societal formalities, new ideas about casual living, leisure time, within the beauty and efficiency of a servant-less home are all influences that Nancy, a generation younger than Wright, added to the program.

A proper ending to this story on the designer/client relationship speaks to Wright’s uncanny ability to respond not only to client needs, but also to individual personalities, without muffling his unmistakable voice in the least. It is eloquently summed up in a letter written by Gene Masselink , to Nancy Willey from La Hacienda: Chandler, Arizona, dated January 16, 1936. “The midnight visit to your House on Bedford Street last week was lovely and I enjoyed it immensely – happy to have the opportunity of driving Mr. Wright up to see you. At so many of Mr. Wright’s lectures he is asked ‘what about the client – where does he enter in?’. Your house which is so essentially your house in every sense seems to be the perfect answer.”