Willey House Stories Part 3 – The Inner City Usonian

Steve Sikora | Jan 31, 2018

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

Header image by Matt Schmitt

When Nancy Willey first approached Frank Lloyd Wright she described the lot she and Malcolm had recently acquired in her introductory letter.

“We have an intriguing lot. It is at the end of Bedford Avenue (sic) and Prospect Park; the street ends at the top of a hill that overlooks the Milwaukee railroad lines (we like them), the Mississippi River, the Lake Street bridge, the farther distant view into St. Paul, and the Minneapolis industrial sky-line in the west. In fact, we have seventy-five percent of the horizon.

The lot is only seventy-five by one hundred and twenty-eight feet but is so located that acres of railroad and city property and a grove of white oaks behind the Shriners’ Hospital, adjoin it down the hill below so that the setting affords the privacy, expanse and beauty of a country home-on three sides. On the north side a house would be one more in a row.

The ‘feel’ of the place is something like this–it is decidedly of the city; the view consists of the lights of the city, the bridges, the winding river, the curving tracks, grain elevators–yet is sufficiently apart from and above the city and neighbors (on three sides) to afford the joys of seclusion, retreat, freedom and breadth of outlook.

And all this with nearness to our work (the university) and our friends-isn’t that splendid?”

Beguiling as it was, her description of the lot clearly painted a picture of an urban setting, albeit one with a lovely vista. Photos from Nancy’s personal photo album dating back to the 30’s and 40’s show a view to the south that appears almost bucolic, the house sited on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River valley. In a series of grassy terraces the landscape between Willey and the river was broken only by railroad lines and further below, The Shriner’s Children’s Hospital, nestled in a copse of oaks. The bluff top like others flanking the river was historically an oak savanna. The native trees that proliferate in Prospect Park today are still predominately Burr Oaks and Cottonwoods. The trees at the Willey House are wild holdovers Malcolm and Nancy left to mature. The river valley below was initially deforested in the 1860’s, by lumbermen jobbing for the Weyerhaeuser mill.

Nancy Willey’s Photo Album

In a 1930’s photo, the view from the fireplace hob, was one of un-obscured horizon and framed the Lake Street bridge crossing the Mississippi River. Snapshots document Malcolm walking the dogs down the grassy slope. Exploiting this vista visually, physically and spiritually was the opportunity that Wright recognized and seized upon in this small commission.

Nancy Willey’s Photo Album

Nancy Willey’s Photo Album

Because Frank Lloyd Wright turned the house ninety-degrees from the street and directed it toward the south, it is disassociated from the neighborhood. To the north, Bedford Street SE is a solid row of houses, all behaving in a similar, predictable manner; each two-story, standing proud on their lots, full basements tucked beneath, all with an identical setback, garages tucked behind, accessed via long driveways or more commonly from the alley.

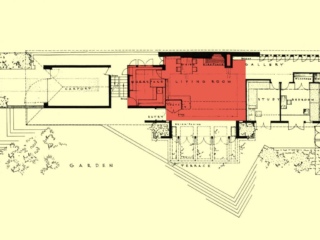

Unlike the modern urban infill model, Willey makes little attempt to blend with the existing homes, eccentric as they may be. Although granted approval by the city fathers, the Willey House seems to violate the usual setback and lot line restrictions. Contrary to the rest, this building’s mass appears to be pressed into the hillside it resides upon, and exhibits a characteristic now associated with the suburban cul-de-sac; the front and center presentation of a garage door. From the neighborhood and alley sides, the house paints an imposing picture. The only thing it seems to welcome is suspicion. In the January 1938 Architectural Forum, Wright confirmed his intent “The plan protects the Willeys from the neighbors, sequesters a small garden and realizes the view to the south under good, substantial shelter.” And he delivered exactly that, a peaceful Shangri-La for his clients in the center of town at the expense, perhaps, of the neighbors. From the exterior, garden privacy is well enforced on three sides. When standing up in the yard itself, there is little sense that the surrounding homes even exist. What is a brilliant site-specific solution here; the creation of total street privacy with one side of the house fully exposed to secluded outdoor space, is repeated time and again in later Usonians, even in cases where the nearest neighboring resident may be at some distance.

Courtesy of University of Minnesota Archives

The lot Malcolm and Nancy purchased was the last available on the east side of Bedford Street. Their yard was once open space local kids used as a de facto playground, more important, it framed a common vista shared by the community. When the house walls were being laid out, a contingent of neighbors, and one in particular, objected. She referred to what was going up as a “spite wall.” In a letter to her mother Nancy recounted “Do you remember those horrid fairy tales we used to read, where there was a dragon whose breath breathed fire that scorched up the countryside. Well, the second neighbor down is the original.” The question of who owned the view was at issue but Wright’s infamy was also a contributing factor “…a great brick wall without any windows in it…and the lord only knows what would go on behind that brick wall, for that Frank Lloyd Wright has a bad reputation…”

Nancy was made to feel so miserable that even though she had jumped through the requisite, legal hoops mandated for city approval, she was not convinced that an unrelenting, disgruntled neighbor could not cause her trouble. She determined her legal vulnerability was 7 feet. She called Wright to ask if he could reduce the length of the house and also sat with A. C. Dahleen, her builder, to see if they could do the same. Both parties quickly reached identical conclusions. It was impossible to shorten the house and still save it. At wit’s end, armed with a book of Wright’s work, Malcolm paid a visit to the disquieted neighbor and was able to calm her down by showing her that they would not be building an “ugly monstrosity” at the end of the street. As it turned out, the neighbor had mistaken one of the stakes in the lot marking the steps as the end of the house and was somewhat pacified by the clarification, but still remained skeptical.

The Willey House was a watershed for Frank Lloyd Wright. It represented the beginnings of Usonia; a compact, single story, L-shaped plan with rooms arranged inline, even though the plumbing and mechanicals were not yet co-located in a utilities core for economy, like later houses. There was another important exception. Usonian homes that followed were primarily envisioned as suburban, exurban or at a minimum set on lots large enough for home agriculture, whereas Willey is decidedly situated in a dense urban setting. Unlike the outer rings, inner urban settings are subject to constant dynamic change as cities modernize and increase in population. And change did come. Which brings us to one of the most persistent stories in Willey House mythology. There are two parts to it.

On October 11, 1955 Malcolm Willey sent a final letter to Frank Lloyd Wright. It read, “The motor age is catching up with Minneapolis! A gigantic freeway system is in process of planning and according to present intentions, the new superhighway will go directly through our living room or at least through our front yard. I thought you would be interested in this horrendous possibility. The only consolation, if there is any at all, would be that we would have the fun of having you do another house for us.” A story we were told repeatedly, one that persists to this day, was that the routing of Interstate Highway 94 was changed at the eleventh hour, in order to protect the Willey House. According to legend, the Prospect Park neighborhood rose up in defense of it. When we first took possession, the house had been left unattended and consequently breeched by trespassers on several occasions, radiators cracked and missing, utilities shut off for years, and water flowed in freely from every direction imaginable and others. A building inspector who was assigned to the neighborhood would show up periodically to check on our careful progress. When asked why, after years of disrepair and abandonment he never condemned the house, as would have been the case for a structure in this condition in any other neighborhood, his response was, “Do you think I’m going to condemn a house built by Frank Lloyd Wright that they routed the freeway around?” Story part 1: the freeway was rerouted to save the house.

As far as I have been able to ascertain, part 1 of the legend concerning the neighborhood rallying to save an architecturally significant house is not entirely accurate. However, it is a prime example of how a myth, in itself, may have helped to save this historic property. A version of the story is repeated in the book Under the Witches Hat: A Prospect Park East River Road Neighborhood History 2003, although it is expressed a bit differently, and it also contains part 2. “The alignment of the I-94 freeway was scheduled to demolish the house; neighborhood pressure resulted in the alignment being changed, but the house now faces the freeway wall so its original view has been lost.” It’s true that a small cadre of activist residents lobbied to modify the routing of the freeway but not for the sole purpose of preserving the Willey House. It was to urge the Highway Commission to utilize a route already followed by existing rail lines and to keep the Prospect Park neighborhood from being sliced into pieces, a fate that befell the primarily African American, Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul, a short distance away. When all said and done, more than 100 homes were still lost, and the neighborhood was separated from the river to accommodate interstate motor traffic. In part 1 of the story, the good news is, the freeway gets re-routed around the house thanks to neighborhood advocates. In part 2, the bad news, the freeway noise barrier still manages to ruin the view.

The National Register of Historic Places nomination form for the Willey House, written in 1984 is a perpetrator of this myth and also contains other pieces of misinformation. The most persistent of which reads: “The Willey House at 255 Bedford Street Southeast in Minneapolis is situated on a long and narrow corner lot. It lies on a slight ridge such that, originally, a view was afforded of downtown Minneapolis and the Mississippi River Valley. However, a freeway sound barrier now obstructs the intended view defeating the original design focus.” One might guess that the nomination was written from the curb, because that short passage, so often repeated, including in the book mentioned above, is utterly incorrect. It is accurate to say that the view from the street, was blocked by the noise wall. However, the house and yard rise above the level of the wall. The view from there remains. As stated, but not for the reasons claimed, the river can no longer be seen. But that loss is not a result of the interstate freeway nor its sound wall. It is because the urban forest has regenerated since the 1930’s. Even in winter months, the branching of the trees alone is so dense as to obscure the river. What clearly remains of the original outlook is a panorama of the distant horizon. The Prospect Park neighborhood caps the highest ground in Minneapolis. The Witch’s Hat water tower sits at the apex, 951 feet above sea level. Floor grade level at the Willey House rises above the surrounding landscape to approximately 910 feet. Using a telescope from the living room, Buck Hill, a ski hill located in the suburb of Burnsville, some 20-road miles away can be seen.

University of Minnesota Libraries

In the early years, the vista was expansive, lending the impression of a peaceful, countrified setting. The hillside extending down to the river was virtually wild prairie. The street was unimproved at least well into the late 1930’s. Therefore it is little wonder that accounts of the house placed it at the edge of Minneapolis. In a 1938 New Yorker column, Lewis Mumford described the Willey House location as “on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi at the outskirts of the city, where Minneapolis becomes St. Paul without anyone but the taxpayer being the wiser.” The fact of the matter is that the house is on the edge of the city as implied by Mumford, but only because one street to the east is the dividing line between Minneapolis and St. Paul. Both cities were developed to the boundary line. So here we had Frank Lloyd Wright, significantly building his first small house for a modern couple of moderate means. Just as significant is where he built this new kind of house, not in a leafy suburb but smack in the middle of town, thanks in no small part to a city lot with an expansive view. The site did not help to inform Broadacre City but these new clients most likely did. In Usonia: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for America, Alvin Rosenbaum reports that the Willeys shared a report Malcolm wrote for the White House, The Agencies of Communication. His paper linked the issues of current developments in communication and transportation as together “extending the radius of man’s contacts, a fundamental concept in Wright’s exposition of Broadacre City.”

In his introduction to the book, Rosenbaum writes “Usonia was Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision for America, a place where design commingled with nature, expanding the idea of architecture to include a civilization, a utopian ideal that integrated spiritual harmony and material prosperity across a seamless, unspoiled landscape. Usonia was a state of mind, combining an evolving prescription for the elimination of high density American cities and their replacement by pastoral communities organized around modern transportation and communications technology with a new type of home for middle-income families.” Technology was making it possible to increase the distance between residents and services in this emerging, modernized world. But Rosenbaum makes another excellent point. Usonia was as much an ideal as much as a specification. The sense of seclusion embodied at the Willey House cannot be attributed to a suburban setting.

Nancy Willey’s Photo Album

Instead it is a state of mind or a separate reality conjured by Wright that might help explain why Willey still feels so transformative. Surprising even, is the volume and diversity of wildlife drawn to this tiny oasis. Besides the obvious songbirds, squirrels, raccoons and rabbits one would expect in the city, the Willey House hosts its fair share of wild creatures from coyotes, woodchucks and opossums, to owls, hawks, eagles and wild turkeys, even deer visit on occasion. The revolving cast of native fauna prevents us from cutting back the thicket long overgrown in the yard. The scene was lovely in its native state and remains so in its own way today. Freeway intrusion or no, I’d argue that the microcosm and “new reality” Wright shaped for Nancy and Malcolm Willey in Prospect Park could have been no more utopian had it been built in Erewhon.