Willey House Stories Part 2 – Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Steve Sikora | Dec 14, 2017

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

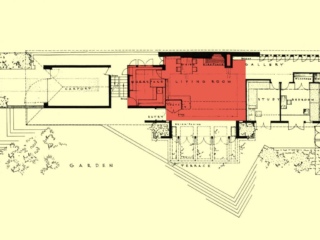

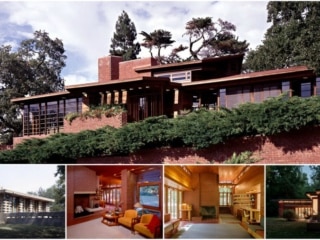

This story began with the rediscovery of a draft article by Minneapolis architectural historian and writer, Richard Kronick. It was titled The Malcolm Willey House, the First Rambler. The subtitle piqued my interest due to my ongoing fascination with Frank Lloyd Wright’s effect on vernacular architecture. Growing up in Southeastern Wisconsin, where the landscape is blessed with an inordinate number of homes, churches, park shelters and dental offices inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, the rambler, or ranch house, reference made a certain sense to me, even though it presented a kind of contradiction in terms. After all, Wright’s houses are considered masterpieces of architecture. Intuitively a “masterwork” and a product of “mass production” should appear at opposite ends of the spectrum. I believed, and still do, the Willey House to be a lot of things, and a rambler was not necessarily one of them until recently. The Willey House represents a turning point in Wright’s career. It is the mark on the timeline where Wright learned how to accommodate the needs and desires of the middle class. William Allin Storrer wrote that Willey “represents a major bridge between Prairie style and the soon-to-appear standard L-plan Usonian house.” In the Architectural Forum, Wright himself proclaimed “the house emphasizes the modern sense of space by vista inside and outside, without getting all modernistic.” Gene Masselink said, “Nancy’s house was the plow that broke the plains.” Nancy Willey understood her house to be a pioneering example of the servant-less house: “I asked for simplicity. Those who came after me demanded it.” In aesthetic character, the Willey House bears a passing resemblance to Taliesin. But manifests in a completely unique way for its monolithic use of brick, to shape interior and exterior walls, floors, fireplace, terraces, steps and driveway, as if all the parts were drawn from a single mold. In a material sense, Willey is related to Wright’s textile block houses, while in plan it is clearly Usonian. It is only when we take off the Cherokee Red-colored glasses, that it’s easy to see the floor plan is also that of a ranch house.

I asked Richard if he was serious about the implied claim, he was, but said it would be difficult to prove conclusively. After studying the subject I’d have to agree. There are far too many influences, from traditional Spanish ranchos to Gustav Stickley Craftsman plan books, let alone the pioneering work of architects Rudolph Schindler, Henry Palmer Sabin, William Wurster, Harwell Hamilton Harris and of course Wright himself to point a finger any one starting point. Add to that, the definition of rambler—aka ranch house—is far too broad to suggest a single genesis. All that said, Frank Lloyd Wright at the very least deserves credit for designing what amounts to a mature ranch house in the year 1933, with features not fully employed by Cliff May, the celebrated father, and leading practitioner of the style, until the 1950s, a full decade or two before they were trending.

But how is it possible that something like a California ranch house could arise in a place like Minneapolis, Minnesota?

Since “ranch house” is both an architectural style and a broad real estate category into which miscellaneous one-story homes get tossed, let’s start with definitions.

Ranch house definitions

“Rambler” is simply another name for “ranch house” or “California ranch house.” The term rambler is more commonly applied in the Midwest.

Merriam Webster definition

1: the main dwelling house on a ranch

2: a one-story house typically with a low-pitched roof and an open plan

Wikipedia definition

Ranch (also known as; American ranch, California ranch, rambler, or rancher) is a domestic architectural style originating in the United States. The ranch house is noted for its long, close-to-the-ground profile, and wide open layout. The house style fused modernist ideas and styles with notions of the American Western period of wide open spaces to create a very informal and casual living style.

Realtor.com definition

The ranch house is so simple; it may seem to have no particular style at all.

This quintessentially American design grew out of the desire for homes that allowed for more informal family living in the suburbs, which sprang up in the mid- to late-20th century.

Cliff May, the reputed father of the American ranch house style was intentionally vague in his definition. He said: “If it lives like a ranch, it’s a ranch.”

Finally this, in his book Ranch House, Alan Hess is anything but ambiguous:

A Ranch Definition

- A one-story house with a low-pitched, gabled, or hipped roof, with wide eaves

- A house of general asymmetry (in contrast to Colonial symmetry)

- A house with a general horizontal emphasis (in forms, or materials emphasizing horizontality)

- An open interior plan blending functional spaces

- A house with a designed connection to the outside (this can include a U-shaped plan that embraces a terrace patio, sliding glass doors, picture windows, a front porch, etc.)

- A house with informal or rustic materials or details (board-and-batten siding, high brick foundations, dove-cotes, Dutch doors, shake roof, barn door garage doors, exposed rafter beams, exposed truss ceilings, etc.)

- Ornamental elements can include Rustic, Spanish, and French. Colonial, or other traditional styles. Or, with simpler Modern detailing, it can be a Contemporary Ranch House.

- A house whose plan is rambling and suggestive of wings or additions

By every description, especially the comprehensive Hess definition, the Willey House qualifies as a Ranch House.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s influence on Cliff May

The men were indeed acquainted. In his biography, Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright, Brendan Gill sheds some light on the relationship between the architect and the builder. “May and Wright were friendly acquaintances. On the occasion of their last meeting, at Taliesin West, May brought all of his Wright books to be autographed; Wright signed them at top speed, then tossed them one after another through the air to May, who scrambled to catch them as if they were so many basketballs.” From Gill’s description of the scene it is fair to say that May was at least a smitten admirer, if not indeed an adherent of Wright’s ideas, as his later work certainly suggests.

Gill goes on to say that May had just designed a house for Harold and Mrs. Price when they visited Taliesin to discuss Price Tower. “Strolling about Taliesin, the Prices perceived that many of the attributes of their May house had been anticipated by Wright 40 years earlier—a simple, natural use of stone and wood, the low horizontals of the wings of the house running along the earth and seeming to grow out of it, the cedar shingled roofs with their broad overhangs.” Although Wright was complementary of the ranch that Cliff May had built for the Prices, it is no coincidence that not long after, the Prices had not one, but two Wright-designed homes.

Photos of May’s first houses were difficult to source. But, in a serendipitous twist, my wife and I discovered several issues of American Home magazine at the bottom of a box, beneath a stack of other boxes, while cleaning out my late father’s basement. The February 1935 issue had an article on Cliff May entitled “Re-creating an ancient Mexican hacienda.” May, a design build contractor began building in 1932. However, the earliest examples from the Cliff May Miracle Company, referred to as “haciendas” were impersonations of Spanish adobes found throughout southern California. They even imitated the thick earthen walls through the artful use of wood frame and stucco with solid wooden doors that opened to a paved outdoor ramada. A sleek, modern aesthetic was not applied to May’s rustic ranch houses until later in his career. May’s evolution is likely due in part to the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright, as evidenced by the breakthroughs in design of the Willey House, the date it was drawn by Wright (December 1933), and the date constructed (1934). Willey existed in complete, simple, modern splendor at a time May was still building ersatz adobes.

Cover, American Home Magazine.

Page one of article on Cliff May.

Floor plan, May ranch house.

Publication and media visibility

Throughout the mid-to-late 30’s, the Willey House was well publicized, appearing in influential magazines and trade publications; the January, 1938 Architectural Forum, the November 1935, Architectural Record, the March-April 1934, Trend: An Illustrated Bi-Monthly of the Arts, books like Tomorrow’s House by George Nelson and Henry Wright, and in consumer-facing newspapers and periodicals like the February 12, 1938, The New Yorker. All of this exposure was directed at Americans emerging from the Great Depression, seeking less constrained, more modern ways to live. Photos of the house would have been seen by legions of architects, builders and potential homeowners alike, stimulating interest because it was designed to suit a progressive, young couple. The house was full of tantalizingly fresh ideas just right for the times.

One significant distinction between the Prairie houses and the Usonians was the way Wright connected inhabitants with nature. Prairie houses are rich with ornate abstractions of natural forms, depicted in art glass, fixtures, furnishings, fabrics and murals. Usonian houses, beginning with Willey, are essentially minimum houses, purposely stripped of extraneous decoration. Here, instead of implied natural forms, for inhabitants Wright creates direct, visceral experiences with nature. Living room floors extend themselves into the landscape, window glass explodes the edges of rooms and vast swaths of wall open to the outdoors. Wright, a native of the upper Midwest was already happily living his own alfresco lifestyle at home in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Several rooms at Taliesin that shelter beneath a common roofline, require exiting the house and re-entering to gain access to an adjacent space within, as at Willey. Working in Los Angeles during the early 1920’s would have reinforced Wright’s instincts and helped inform the pleasures and health benefits of melding inside with out. His client, Nancy Willey was herself an advocate of informal outdoor living. In a 1996 video interview by Lief Anderson and John Clouse, Nancy revealed that in her youth, the Boyd family summered in Sag Harbor, her birthplace. She portrayed her early years as an existence highlighted by daily swims in the ocean, regardless of temperature and where outdoor dining was the norm. Giving Nancy direct access to her garden and the Mississippi River bluff the house was situated on would have been of great appeal to her as well as a natural connection to the site. The second Willey scheme was designed a year and a half after Wright met the Willeys. By that time he would have known and understood the couple much better than he did when the initial scheme was drafted. The Willey’s agreed. This house suited Wright’s “best of clients” exceedingly well.

Photo by Matt Schmitt.

Call it what you will, the Willey House, it seems, may be where all of the critical elements of the American ranch house first coincided in time and place. A compact home for the middle class, 1-story, inline plan, indoor/outdoor living, exterior terrace accessible from every room in the house, a new sense of space that seamlessly merged interior and exterior spaces, expanding the impression of scale that predicted the direction domestic architecture would follow for the next several decades. I recall a cartoon published in the late 30’s, an obvious parody. It lampoons Wright’s influence on the domestic scene; an entire neighborhood of Fallingwaters, standing side by side, each with its own waterfall. The cartoon is a perfect illustration of the dialectical tension in Wright’s portfolio. He is capable of imagining something as utterly singular as Fallingwater, while just prior, conceiving the template for what was to become one of the most prolific housing forms to populate the post-war, American landscape. The Willey House itself, in detail and execution is a work of art, but the ideas underlying it are readily replicable on a mass scale. In his February 12, 1938 column for The New Yorker Lewis Mumford wrote; “These two houses (Fallingwater and Willey) show Frank Lloyd Wright at the top of his powers, undoubtedly the world’s greatest living architect, a man who can dance circles around any of his contemporaries.” While he praised Wright’s mastery in both instances, he did not point out the contradiction that distinguishes these two very different houses. One, instantly became an enduring icon of modernism. The other, and no less important, foretold the shape of things to come.