Willey House Stories Part 10 – Lo on the Horizon

Steve Sikora | Jan 24, 2019

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

All photos by Steve Sikora unless otherwise noted.

The story always goes something like this. It’s 1932: Malcolm and Nancy Willey pay a visit to Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, to review the plans for the house Frank Lloyd Wright has agreed to design for them. Seeing activity everywhere except in the Drafting Room, the Willeys come to suspect they are the great architect’s only clients. Their suspicions are ultimately confirmed when called to lunch. Posted somewhere between the Drafting Room and the lunch table, they inadvertently discover their initial inquiry to Mr. Wright. Scrawled across the face of the letter is the giddy pronouncement: “Eureka, a client!” This is the most frequently repeated story related to the Willey House. It’s a good one. People on tours tell me this story. Sometimes it’s not even associated with the Willey House. Like the story of the client calling Wright during a rainstorm, saying water was dripping on his head, and what should he do, “Move your chair,” says Wright to Mr. Whateverclient depending on the source. The “Eureka” story has appeared in books, and was even popularized in the Ken Burns documentary Frank Lloyd Wright, where architect Robert A. M. Stern recounted it on camera. Curious about its origin I reached out to Mr. Stern, who responded saying “To the best of my recollection the story was told to me by Prof. Vincent Scully of Yale. But who knows, it may be apocryphal?”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s desk in the Taliesin Drafting Room.

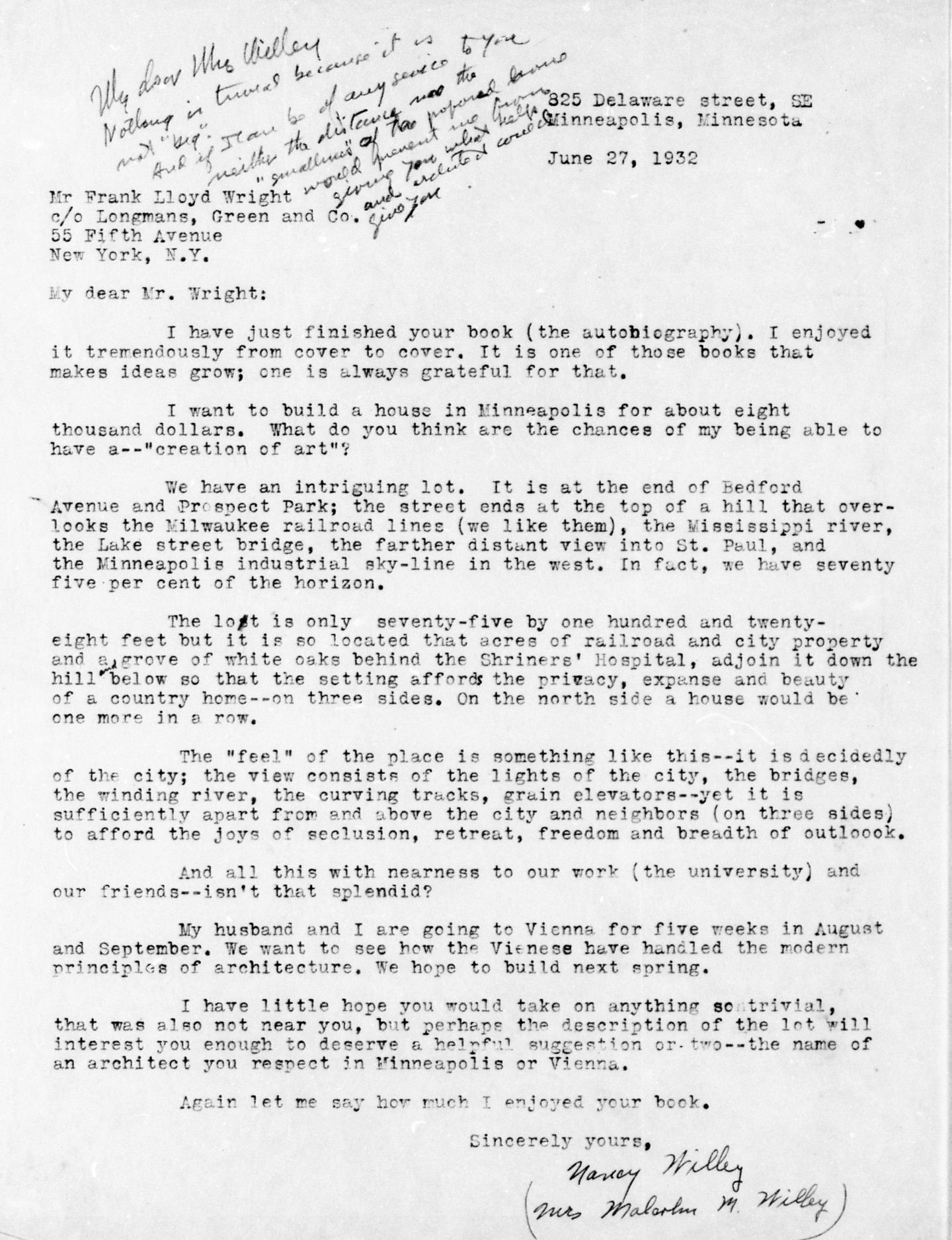

Filed in our collected correspondence between Taliesin and the Willeys, is a copy of Nancy’s initial letter. The text matches exactly the letter that Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer printed in Frank Lloyd Wright: Letters to Clients. Our photocopy, I noticed, was unsigned. It was likely made from of a carbon copy that the Willeys retained. Ours was sourced from a collection housed at the University of Minnesota, Anderson Library where Malcolm thoughtfully preserved the Willey’s correspondence (mostly the Taliesin side of the conversations) for posterity. It seemed the only way to get to the truth of this was to track down the signed original that was sent to Frank Lloyd Wright.

I reached out to the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library. Archivist Shelley Hayreh located the original and examined both the front and back of the letter. She assured me there was no “Eureka!” to be found on either side of the document. However, there was an inscription. Wright had hand-written his eloquent response to Nancy directly at the top of her letter. “Nothing is trivial because it is not big…” (Willey Stories Part 6) He would have then asked Karl E. Jensen, his secretary in 1932 to type and post his response.

Nancy Willey’s initial letter to Wright with his response to her hand-written in the upper left corner. Courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). All rights reserved.

So where does the “Eureka” story come from? Like so many things in the mythology of Frank Lloyd Wright good stories are repeated often enough to become legend. As in any oral tradition, or childhood game of telephone for that matter, the words are embellished and the storyline distorted in the telling and retelling. This one even gained a crowd-pleasing a punch line. In the case of the “Eureka” story, however, a version more closely aligned with the facts, is in my estimation better than the mythologized one. This more authentic account can be found in Alvin Rosenbaum’s remarkable book Usonia: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for America. The book contains a great deal of previously unpublished information sourced directly from Nancy Willey via her friend and writing partner Lief Anderson, in 1989. One passage in Usonia has familiar ring to it:

“As they walked through the studio door to go to lunch, they stopped to read a sign posted on a bulletin board:

Lo! On the Horizon a Customer Appeareth. By God, He shall not Perish on this Earth.

‘I wonder what rascal did that,’ Wright obviously embarrassed, said as they passed. The Willeys were astonished. ‘Our first surprise was that he accepted us as clients. Our second surprise was that he was in the midst of a school rather than working with clients, with telephones ringing, a busy celebrity at work. Instead we found we were his only clients and that his work-Broadacre City-was all theoretical. He appeared an estate farmer, at home, a place filled with music, surrounded by his students.’”

The story is corroborated in a videotaped interview of Nancy conducted by Leif Anderson and John Clouse in 1996. In it she gives a near identical recounting of the episode, except that it is Wright who reads the note posted on the bulletin board aloud and chuckles at it.

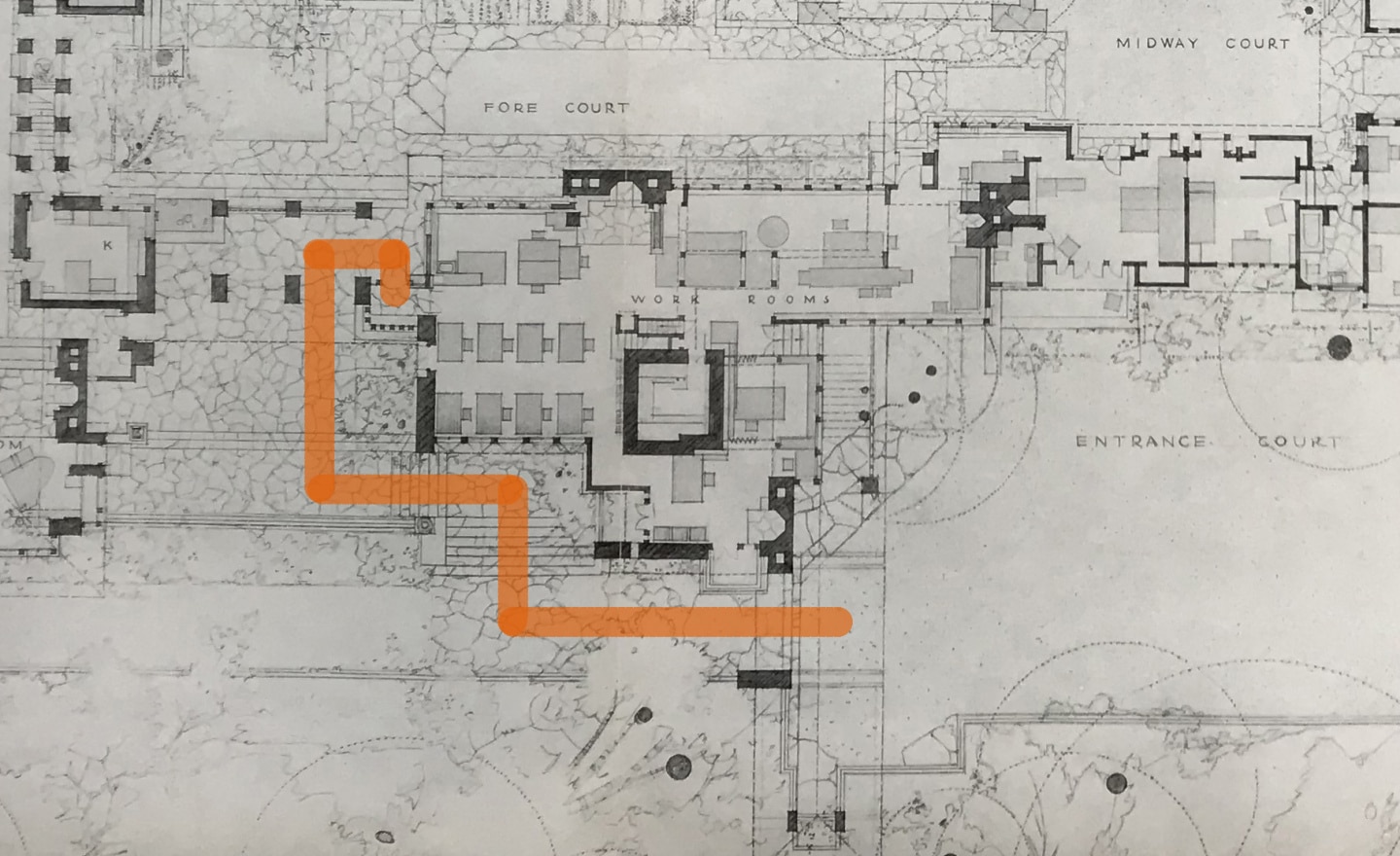

I turned to Keiran Murphy, historian at Taliesin Preservation, Inc., to see if she could help solve the problem of the existence of a bulletin board at Taliesin. In her helpful response, she reminded me of other essential questions surrounding this story. The orientation of functional spaces at Taliesin is physically different today from its arrangement in 1932. The locations of the meeting place and lunch may not be where we think they’d be. I’ll confess, in my mind’s eye, imagining the Willeys accompanying Wright to lunch, always began in the main area of the Drafting Room (think of those photos of Wright’s desk in front of the vault surrounded by his young apprentices). The Willeys, trailing Wright exited the studio via the vestibule Dutch door. They then proceeded through the loggia down a few steps and veered left into the main residence, to dine in the Living Room. However, in 1932 the procession from Drafting Room to dining did not mean entering the main residence. All dining took place above the Tea Circle in the Hill Wing. This also calls into question which of two studio doors and which of two exterior stairways might have been used to get there. The correct answer depends upon where within the Drafting Studio they met. It is subdivided into three distinct spaces: the Drafting Room, the Back Office and the Front Office. A bulletin board could have been anywhere along the path, but which path did they take?

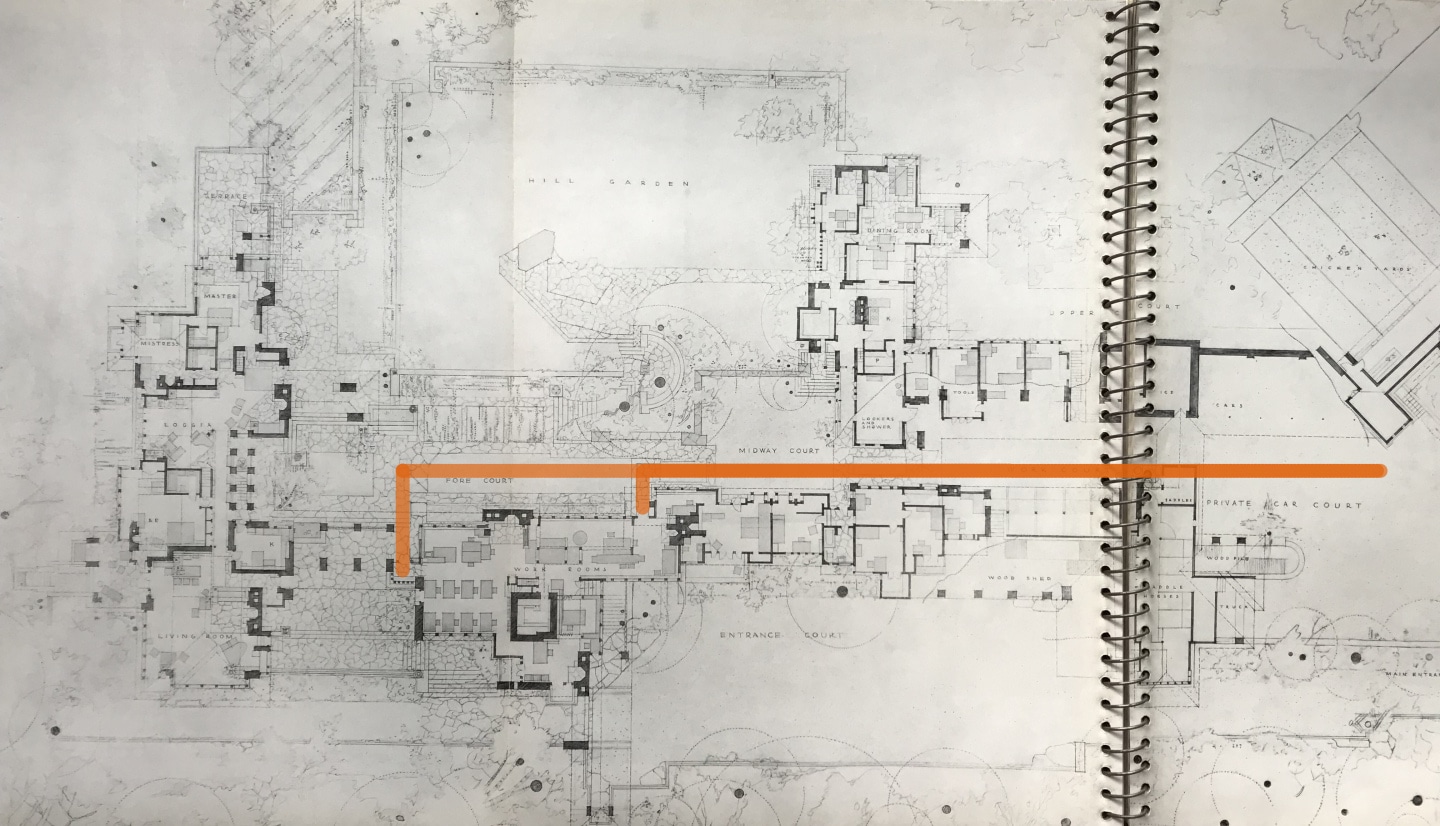

The path from the Fore Court outside the Drafting Room, through the Tea Circle, proceeding toward Hill Dining Wing.

To further complicate things, for a visiting client in 1932, the sequence of the three spaces in the Wright’s Studio may have been thought of in the exact opposite order we perceive them to be in today. In its current configuration, the entry to Taliesin is made from the partly cantilevered Lower Parking Court, originally called the Entrance Court, (shown in the plan drawn for the January 1938 Architectural Forum) which did not exist in 1932. Today, visitors mount a flight of stone steps emerging from beneath a covered loggia separating the main door to the residence off to the left and the vestibule door to Wright’s Drafting Studio, which is to the right. In short, at the time of the Willey’s visit, one entered Taliesin by a very different path. In 1932, the entry was a straight-line procession, which began at the Rear Parking Court (Back Court), passed through the graveled Work Court and Midway Courts until arriving at the Fore Court (Garden Court) outside the Drafting Studio. The first studio door they would have encountered led to what was called at that time the Front Office. Today, we think of it as the back door to Wright’s Studio. The name Front Office would suggest that it was at least for a time, the primary point of entry, where clients would be received. Although, just two years later, Edgar Tafel recalls Wright standing at the Drafting Studio door to greet Edgar Kaufman with the phase “E. J. we’ve been waiting for you!” as Kaufman mounted the steps. The steps he cited are the three that lead to the vestibule entrance of the Drafting Studio. If Kaufman entered by this route, it is quite possible the Willeys did also. A recent issue of the Journal of Organic Architecture + Design dedicated to historical Fuerman photographs of the constantly evolving, three Taliesins show the Fore Court from a number of angles that help to recreate this earlier Taliesin.

The lines show the path a visitor would take from the Parking Court, through the Work, Midway and Fore Courts to the Drafting Studio by two possible doors. Photo courtesy January 1938 Architectural Forum.

Contemporary view from the Fore Court toward the Midway Court

In Edgar Tafel’s book About Wright, one of the first members of the Taliesin Fellowship, Yen Liang, described the entry sequence when he, himself arrived at Taliesin in 1932. He first encountered the Stable thinking it perfectly suitable for human habitation “From the driveway, one structure looked like a clean, nice building where people could live without shame-but it was the stable. It spanned the back drive…” From the Rear Parking Court visitors first passed by the Stable and Pig Sty on their approach to the main Residence or Studio. Because the entry sequence was different from today, also implies that what we consider front and rear of the Drafting Studio today could have been reversed.

Once inside the Drafting Studio, the presentation meeting could have taken place in any of three areas; the main area with fireplace, what we think of as Mr. Wright’s Drafting Room is one possibility. It was in this space in 1932 where all draftsmen and apprentices worked. Wright may have asked them to clear the room for a client presentation. The Front Office where today stands a conference table is another possibility. It is unknown what furnishings existed there in the early 1930s. But being the public-facing Front Office it may have been the furthest extent to which clients were invited into the studio proper. Or finally the meeting could have taken place in the Rear Office, the spaces behind the drafting room, and a place that former apprentice Lucretia Nelson recalled Wright meeting with at least one other client privately. This was Wright’s private office when the Taliesin Fellowship still worked exclusively in the Drafting Room. It became Gene Masselink’s office after the Fellowship moved to Hillside. So we have three possible locations and a reasonable rationale for each as to why it could have been a logical meeting place, but no forensic evidence to prove which.

Next in question is the route from meeting to lunch. At some point along that pathway was a bulletin board. In the early 1930s meals were served in the Hill Wing, not in the living room or the soon to be constructed Hillside dining room. Depending on where in Wright’s Studio the meeting was held, the Willeys could have exited through the Drafting Room vestibule, in which case they would have walked through the Tea Circle on their way to the Hill Dining Wing or exited through the Front Office door, in which case they would have passed through the Midway Court and mounted a different flight of stairs to Hill Dining. Either route would have offered potential locations for a bulletin board, though one is not known today. Keiran Murphy suggests a couple of strong contenders. “It’s very possible that they saw the sign in the vestibule of Mr. Wright’s Drafting Studio” (which, at that time, was the only studio at Taliesin). She estimates that given Wright’s propensity for grandeur, he would have likely used the main area of the Drafting Studio to present to his new, young clients and used the vestibule door as an exit to lunch. “They also could have seen a sign on the door leading into the Hill Dining room, which is in the Hill Wing.” Here, there was the Fellowship dining space as well as a private dining room exclusively for the Wrights and their guests.

Contemporary view from the Midway Court toward the Work and Parking Courts.

Returning to the collected correspondence between Nancy Willey and Taliesin helped shed further light. There should have been a record of two visits by the Willeys; the first, for clients and architect to meet and establish their personal wants and needs, and a second meeting where the Willeys were presented with the plans. The historic record creates a problem with both versions of the story as told. Here is why. A presentation meeting would not have been the Willeys’ first visit to Taliesin. It would have been the second.

On July 12th, 1932 Karl Jenson wrote to Nancy Willey, “Mr. Wright would be happy to have you drive over to Taliesin for a discussion of your needs, and stay overnight here if you possibly can.”

Tuesday, July 19th Nancy wrote, “Could you see me this Wednesday meeting 4:15 standard Northland bus at Spring Green.”

By Western Union Wright replies, “WILL MEET YOU NORTHLAND BUS AT SPRING GREEN FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT.”

Wednesday, July 20th, 1932 was the first meeting, and Nancy Willey was in attendance alone. Malcolm did not make the trip.

Two days later, Nancy writes, “Mr. Willey is as delighted as I am with the outcome of my visit to Taliesin.”

In a letter of August 11, 1932 Wright tells Nancy. “The plans have gone forward to you – and I like them myself very much.”

The plans were confirmed received by Nancy on Saturday, August 20th, 1932. The plans for Willey House scheme 1 were mailed, not presented in person.

Without a doubt, a first visit to Taliesin was made by Nancy Willey alone, and it was not a meeting to review house plans.

On Nancy’s initial visit, if she had arrived at Taliesin by car she would have happened into the Front Office door because she would have encountered it first, while trying to orient herself after parking at the far end of the complex in the Parking Court. But, considering that Nancy was chauffeured from the bus station, in person by Wright or someone sent by him, she would have been escorted to the Drafting Room and I tend to agree with Kieran Murphy’s assessment that she’d probably have been taken directly to the Studio via the vestibule doorway. But because this meeting was not for the purpose of presentation, I doubt that architect and client would have ultimately huddled in the studio for their conversation.

Understanding that Nancy met with Wright on her own establishes a pattern that continued throughout the Willey House correspondence. The client relationship was always one between Nancy and Frank Lloyd Wright, not with Malcolm. Despite the paternal title – the Malcolm Willey House, Malcolm remained in the background, busy with his career as Nancy played her critical role in helping Wright to redefine the needs of domestic architecture for the rising middle class.

What we are left with are three possible meeting spots, two Drafting Studio doors, two stairways to Hill Dining, two versions of a story, neither entirely correct and one elusive bulletin board. Ascertaining the facts, behind the legend was a bit like solving a riddle. But being confronted with reconsidering the meanings of the familiar spaces at Taliesin proved the most disorienting of all. This exercise in past regression served to remind me, and now you, that with Frank Lloyd Wright, it is never safe to make assumptions about the way we perceive things to be today. Nothing was static in his world, least of all in his own homes. To understand Wright one must learn to embrace the law of change as he did. Like tracing smoke, constant flux may seem to challenge any hope of clear understanding. But allowing oneself to abandon preconceived notions may be the only way to ever flirt with the truth. It is important to accept that it may not ever be possible to completely understand exactly how things were at any given moment at Taliesin. But it is sometimes possible to prove how things were not.

Contemporary view through the Fore Court toward the Residence. (c) Mark Hertzberg

A contemporary view of what in 1932 was known as the Front Office, possibly the first stop for a client or vendor visiting the Drafting Studio. The entry is at the far end of the room.

Edgar Tafel said the drafting Room was the epicenter of Taliesin, “People would come through, to check on their mail, see Mr. Wright about things, seek people working on the boards, make phone calls, and more. Almost certainly, the bulletin board was inside the studio. After all it was the nerve center of the estate.

Taffel had a reputation as practical joker in the Taliesin Fellowship. Wright called him “Joke Boy.” I always thought he was a likely candidate to be the author of the alleged inscription. Then I found this. Tafel’s book About Wright has a page entitled In The Drafting Room. It lists sample writings lampooning local news stories posted on the bulletin board in the drafting room during the fall of 1932, beneath the heading of GOOD CLEAN FUN: the front page, mourning edition, taliesin’s nose knows, Tafel confirms the existence of the bulletin board and places it inside the drafting studio. A recurring character in the contrived news posts is Spring Green jeweler J. W. Zangel who regularly published ads in the personal column of the local paper. Tafel includes a sample entry from the bulletin board that read: “j. w. zangel’s message to taliesin: I see in the near future a customer approaching…before god, he shall not perish from this earth…”

Based on available evidence, the actual sequence of Nancy’s initial visit to Taliesin unfolded like this. She was greeted at the bus station in Spring Green on a warm, Wednesday afternoon in July 1932 and escorted to Taliesin by car. The entrance to the estate was off Highway 23, where the stone gateposts and Taliesin marker are still plainly visible. A graveled drive proceeded Northwest, directly toward the house that wrapped around the brow of the hill. As the road meandered left, it mounted the hill and swept back around the residence. Nancy, being a passenger seated on the right side of the car had nothing to distract her from the natural beauty of the estate as it unfolded. In plain sight the entire time, Taliesin revealed itself slowly as the driveway provided a rotating prospect of house and setting, as if the house were placed upon a turntable. The old porte-cochere that once received guests had been converted to a sunroom years before. Traffic no longer passed through the inner courts of Taliesin. Instead, automobile passengers disembarked in the private Parking Court that Yen Yiang described. From there visitors walked in a straight line through the various courts in order to access the Drafting Studio, at the very heart of the Taliesin. One other possibility exists, because this was likely Mr. Wright’s own car, Nancy may have been ferried to a small space below the studio. Yiang made mention of a new road that veered down in that direction. Though the cantilevered parking court did not yet exist, the stone entry stairway did, suggesting that there was some accommodation for a car or two below the studio and living room.

The red line shows the contemporary entry procession to the Taliesin Residence and the Drafting Studio. Though it was not the most common route for visitors in 1932, it is possible that Nancy Willey travelled this path if Wright’s car was parked below the studio. Photo courtesy January 1938 Architectural Forum.

Because of the burgeoning, newly founded Taliesin Fellowship, by necessity meal times at Taliesin were structured affairs. Nancy was met in town at 4:15PM, well past the lunch hour. Assuming Wright did not personally pick her up, Nancy was escorted to the Drafting Room and entered through the main vestibule door for maximum impact. There she met Mr. Wright. He had been no paying clients for years, and so it is hard to underestimate the importance of the first impression Wright wanted to impose on Mrs. Willey. Other than photos, the first Wright space that Nancy ever experienced was the Drafting Studio. Aspects of this space would be mirrored in her own living room little more than two years later. Upon introduction, she would have toured the studio, and residence before settling in to discuss her dream home. An intoxicating prelude to their formal meeting would be a visit to the Taliesin living room for its extraordinary sense of space and breathtaking vista. Nancy’s programmatic discussion with Wright would take place in an intimate setting. The studio’s Back Office was that, and even featured an outdoor terrace where they may have sat with refreshments to discuss her needs on a warm, late afternoon in July. When called to dinner, Wright guided her through the Drafting Room, cluttered with tables, where the bulletin board scene unfolded. After a laugh at the “Lo on the horizon” posting, they proceeded across the Fore Court and up the steps of the Oak Circle for the visceral beauty that experience provided, arriving directly at the door of the Hill Wing and Wright’s private dining room. There, on a table decorated with arrangements of wild flowers and branches she would have been served a homemade meal, elegantly presented for the seduction to be complete.

What we learn is that while the spirit of the popularized story remains intact, the details could hardly be less accurate. The premise of the story isn’t even correct. It was Nancy who wrote the initial letter to Wright. Malcolm and Nancy Willey never visited Taliesin together to review the plans Wright had drawn for them. And yet, while there is no “Eureka” anywhere in this story, there is a greater underlying truth that is undeniable. The Willeys appeared on the horizon at exactly the right moment, to the their own good fortunes as well as Wright’s. The trivial Willey House commission was more than a ray of hope in the dark morass of the Great Depression. It was a morale boost and first architectural project on the drafting boards of the fledgling Taliesin Fellowship. And it was the spark that lit the inferno of Wright’s astounding achievements during the 1930s. Most auspicious of all, it occurred at in quiet moment before the torrent, when Frank Lloyd Wright could still afford it attention enough to reinvent the American home and his career along with it.

The heart-stopping vista from the base of the entry steps leading to the Main Residence and Drafting Studio at Taliesin.

READ THE REST OF THE SERIES

Part 1: The Open Plan Kitchen

Part 2: Influencing Vernacular Architecture

Part 3: The Inner City Usonian

Part 4: A Bridge Too Far

Part 5: The Best of Clients

Part 6: Little Triggers

Part 7: Step Right Up

Part 8: A Rug Plan