The Role of the Site in Taliesin’s Spatial Experience

Quentin Béran | Oct 6, 2021

PhD student Quentin Béran, shares his experience after a two week stay at Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wisconsin home and studio.

For two years now, I have worked on a PhD about the home and studios of Frank Lloyd Wright, and in June 2021 I had the opportunity to stay at Taliesin for two weeks. Let me share with you my experience on site and what it changed about the perception of the home and studio’s architecture. As for Taliesin West, there is a lot to say about the necessity of visiting Taliesin to perfectly understand the purpose of Wright’s architecture. I decided to explore with you the one example that impressed me the most during my stay on site.

Even if the literature regarding Taliesin discusses a lot the relation between the architecture and its site, most of the photographs of Taliesin focus on the buildings, excluding the capital relation engaged by Wright between the architecture and its site, the Lloyd Jones valley. Taliesin can’t be uncoupled from its natural environment because they are intrinsically connected. To demonstrate it, I will analyze the journey of a visitor of the home and studio from the moment she/he parks her/his car in the lower court until her/his arrival in the living room, the true heart of the building. Indeed, as Wright writes in 1932 in An Autobiography: “Taliesin Sunday Evening Occasions take place in the Taliesin living room number three, the third living room to stand in the same space. The most desirable work of art in modern times is a beautiful living room, or let’s say a beautiful room to live in. And if perpetually designing were perpetual motion the world would have in Taliesin that much-sought-for illusion for the millennium.”

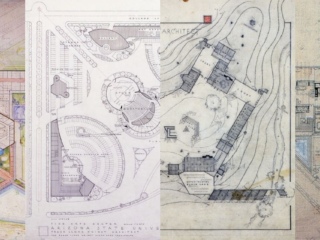

To give rhythm to the visitor’s journey, every step around and inside Taliesin solicits his senses in several ways. Indeed, during his wandering around and within the home and studio, she/he’s confronted with a non-continuous path punctuated by numerous obstacles to overcome as well as a constant alternation between generous and tight spaces, which leads to contradictory sensations of expansion and compression. After entering the lower court, which offers a partially open view of the north-east of the estate, the visitor is forced to pass under the terrace of Wright’s office. Here, the space becomes tighter, and light is significantly reduced. Upon exiting this passageway, views open to the valley to the east. This phase of expansion is followed by the ascent of the covered stairs of the entrance pergola, with no other perspective than the steps to climb, which mark the true transition between the natural wild world, untouched by man, and the one built by Wright. Composed of two elbows, these stairs temporarily block all views toward the site and restrict the movements of the visitor. Wright uses the stairs as a transitional airlock to move him from a contemplative experience of nature to an active experimentation of architectural spaces. At the top of his ascent, the visitor then enters the central courtyard, which again opens onto the vastness of the Lloyd Jones valley. This sequence is followed by the entry into the dark, cramped, and low-ceilinged vestibule, which leads to the spacious, light-filled living room, from which a multitude

It’s interesting to note that both inside and outside Taliesin the view of nature is the determining element in the well-being feeling of the visitor. Indeed, three sequences of the access to the living room are marked by important views on the surrounding nature, which produce a feeling of freedom, expansion, and serenity. On the other hand, the two transitional sequences, the stairs and the vestibule, which offer no view of the outside world, provoke a feeling of confinement and invite people to move towards a larger space. The sequences of volumetric expansion and compression within the complex are thus concomitant with the vision of nature.

Taliesin is characterized by a significant number of perspectives that deliberately open to its landscape context. However, it is also necessary for Wright that the complex provides its initial role of shelter from both the elements and wildlife, as well as from social intrusions. This leads to a certain dichotomy in the design of the building since it must be possible to see from it without being seen in it. To achieve this, Taliesin, while not on top of the hill, is elevated above the valley. In addition, Wright built numerous terraces along the facades which serve the dual purpose of providing a platform to appreciate the valley and to obstruct the views of the interior spaces from a position outside and below the building. Finally, the use of reflective glass blocks the views from outside to inside, without reciprocity. From the living room, Wright also manages to provide significant perspectives of the valley, while still allowing them to take refuge. He achieves this through a spatial design of horizontal layers. Standing at any point in the living room, the visitor can see the valley through the large windows. Yet, when sitting, whether at the table, in the inglenook, or on the living room seats, perspectives to the outside are either blocked by the room’s furniture elements or out of view, as most of the chairs turn their backs to the valley. Thus, when the visitor is in an upright position, she/he benefits from wide perspectives of views of nature, which considerably increase the feeling of space in the living room and give her/him a sense of control over the environment. On the contrary, when she/he is in a seated position, without any perspective toward the outside, she/he experiences the building as a refuge.

At Taliesin, the site conditions not only the plan, the volumetry, and the materiality of the architecture, but also the circulation and the sensations of its visitors, who are continually invited to contemplate the natural setting of the Lloyd Jones valley by Wright.