Plagued by Fire: New Biography Explores the Humanity of Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Sep 26, 2019

In his forthcoming biography, “Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright,” award-winning author Paul Hendrickson delves into the life of Frank Lloyd Wright, covering many controversial and interesting topics including the unmistakable role of fires in his life.

This October, award-winning and nationally best-selling author Paul Hendrickson is releasing his new book, “Plagued by Fire: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright,” a deeper look into the life, mind, and work of Frank Lloyd Wright. In this biography, Hendrickson strives to give a fresh, deep, and more human understanding of the Wright by sharing more about the many unknown and unspoken elements of his life.

The book covers many topics including Wright’s relationship with his father, and his friend and mentor Cecil Corwin, the eerie, unmistakable role of fires in his life, the connection between the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, and the murder of his mistress, her two children, and four others at Taliesin, his beloved Wisconsin home. Below is a brief excerpt from part one of the book.

The book will be released on October 1, 2019, everywhere that books are available, and can be pre-ordered now.

PART I – LONGING ON A LARGE SCALE 1887-1909

“Longing on a large scale is what makes history. This is just a kid with a local yearning but he is part of an assembling crowd, anonymous thousands off the buses and trains, people in narrow columns tramping over the swing bridge above the river, and even if they are not a migration or a revolution, some vast shaking of the soul, they bring with them the body heat of a great city and their own small reveries and desperations, the unseen something that haunts the day.” — Don DeLillo, Underworld

Mother-fueled, father-ghosted, here he comes now, nineteen years old, almost twenty, out of the long grasses of the Wisconsin prairie, a kid, a rube, a bumpkin by every estimation except his own, to a Chicago and North Western train at the Wells Street Station on the north bank of the Chicago River, into the body heat of this great thing called Chicago, on a drizzly late winter or early spring evening in 1887. It is about six p.m. Supposedly he has never seen electric arc lights before. Supposedly he has seven bucks in his pocket. (To get most of that, he has sold off, at old man Benjamin Perry’s pawn- shop on King Street in Madison, some of his departed father’s library, including a calf-bound copy of Plutarch’s Lives. He’s also hocked a semi-ratty mink collar of his mother’s that was detachable from her overcoat.) Supposedly he has managed his secret escape from his broken home on this mid-week afternoon without his two little sisters, who adore him, or his loving, divorced, and impecunious mother knowing. And now, with his pasteboard suitcase, and in his corn-pinching “toothpick” shoes, he’s made it to what he’s so long imagined as the Eternal City of the West.

He’s just one part of this disembarking, suppertime crowd, these narrow tramping columns, anonymous thousands (well, hundreds), drifting out of the depot’s great clock-towered front entry (after having checked his bag at the overnight luggage hold). He’s turning south with them onto the Wells Street Bridge, which is a swing bridge directly outside the front door, not quite knowing where he’s headed, not willing to ask, just surfing along on this strange inland sea, possessed of his own small reveries and desperations and unseen haunts, longing to make history on a large scale, propelled by a “boundless faith grown strong in him. A faith in what? He could not have told you.” So he will write, in the next century, on page 60, of his first version of An Autobiography.

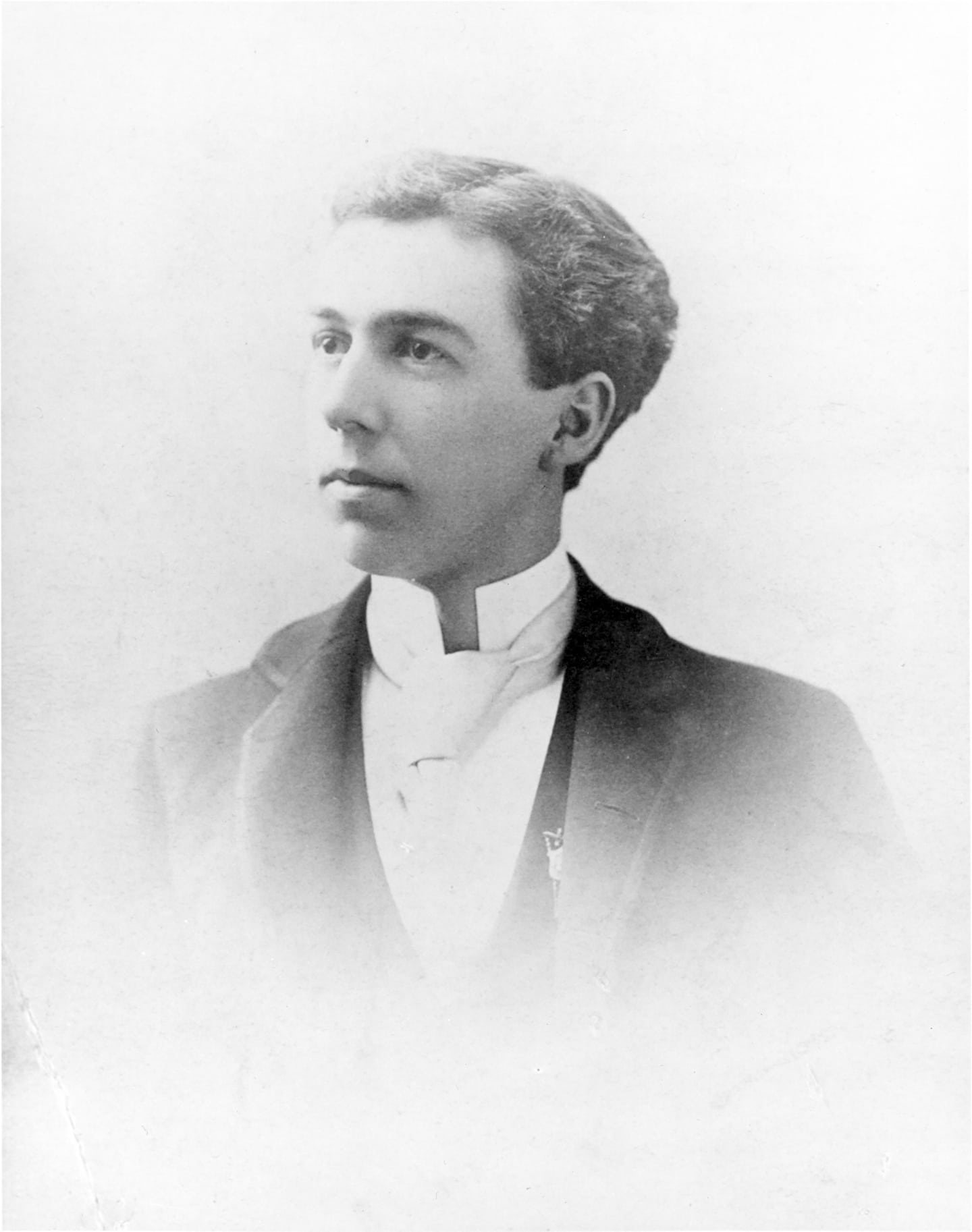

Frank Lloyd Wright, Chicago, 1887.

The boundless belief is that he will somehow turn himself in short order into a world figure on architecture’s stage. It’s not only going to happen, but in not much more than a decade. Frank Lloyd Wright—who will later wish to claim that he was seventeen, not nineteen, at this arrival moment; who wishes to profess to any would-be employer that he’s finished three and a half years of college but has decided to skip his final several months before obtaining his degree because it was all bunkum anyway; who has an extraordinary gift for thinking in three dimensions—has just stepped out into one of the great building laboratories of the globe. Stepped out into a rude, teeming, black-sooted, horse-carted, Bible-belted, prostitute-prowling, not exactly cosmopolitan and nowhere close to eternal metropolis that has been remaking itself since October 1871, when an apocalyptic fire, burning for thirty-six hours, took almost a third of its whole, something like 17,450 structures, practically down to weeds and the sands of Lake Michigan. Stepped out into a city that, in this decade alone, 1880 to 1890, has been doubling over on itself in population—from half a million souls to more than a million. Chicago, which incorporated itself only fifty years ago, is now the most explosively growing place on earth. Because of the circumstances and geography of its location it has also become a world center of architectural innovation and experimentation, not to say a world center of transportation, on both land and water.

(There are six major rail depots here—no other American city has anything like it.) It’s a horse-collared city whose tight downtown building core is hemmed in on three sides by a small river and a great lake: it must go up instead of out, at least inside the horse-collar. In the Lakeside City Directory there are 187 listings for architectural offices—from one-man ops to firms with rows of draftsmen and delineators. Some of these names are already entering American myth: Burnham & Root, Holabird & Roche, Adler & Sullivan, William LeBaron Jenney. This small-town boy, with his large imagination, has struck Chicago, has hit architecture, the mother of all arts (so he believes), at its seeming ripest moment.

It’s such a grand American story: the lowly arrival, the startling becoming, and practically every Frank Lloyd Wright book that’s ever been written, not least his own, has wanted to deal with it in some way or other. Even accounting for all the luck and seized opportunity, no one has ever quite been able to explain how it happened, the realizing part, because artistic genius of this sort, or maybe any sort, doesn’t have real explanation. ∎

Excerpted from PLAGUED BY FIRE: The Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright by Paul Hendrickson. Copyright © 2019 by Paul Hendrickson. Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC