Philip Johnson: 100 Years, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Us

Philip Johnson | Apr 30, 2020

In 1957, architect Philip Johnson delivered a speech to the Washington State Chapter of the American Institute of Architects: “100 Years, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Us.”

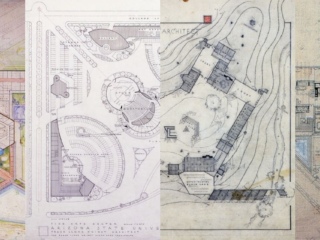

Above left photo: Glass House by Philip Johnson; Above right photo: Taliesin West by Frank Lloyd Wright.

This text from architect Philip Johnson’s speech “100 Years, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Us” has been reproduced with permission from The Glass House, a site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Speech, Washington State Chapter, A.I.A., Seattle; published in Pacific Architect and Builder (March, 1957), 1}, 35-36.

This talk was delivered before the Washington State Chapter of the American Institute of Architects as part of its celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Institute’s founding and was published by the Chapter in its own publication, Pacific Architect and Builder. It is Johnson’s most affectionate, most complete, and most candid discussion of Wright’s work, presented in Wright’s eighty-eighth year while he was very much alive and actively involved in the construction of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Given the usual proscription of the A.I.A. concerning one architect’s criticizing another, the publication of Johnson’s remarks-which are in effect no more salty than the casual commentary about contemporary issues that Wright so regularly dispensed in numerous articles and interviews – was preceded by a disclaimer to the effect that the talk “is probably as provocative as any heard at centennial celebrations across the land . . . the views expressed in this digest of the tape-recorded extemporaneous talk are not necessarily those held by Pacific Architect and Builder.”

Frank Lloyd Wright and Philip Johnson at Yale

Johnson and Wright enjoyed a love-hate friendship which began at the time when Hitchcock and Johnson were assembling materials for The Museum of Modern Art’s “Modern Architecture” exhibition in 1932. When Hitchcock advocated Wright’s inclusion in that exhibition, Johnson was said to have claimed that he thought Wright was dead. Whether he meant it literally or simply artistically is not clear; but news of Johnson’s remarks got back to Wright, who was never reluctant to hold a grudge. Nonetheless, by 1945 the two were surely friends, and in the 1950’s Wright visited at the Glass House several times. On one of these visits, he claimed that the asymmetrically placed Nadelman sculpture of two women was badly positioned; but after moving it to another location near the bar, he had to admit that it looked absurd there and should be restored to its original place.

You have to come to Seattle to get away from the hidebound East Coast, to get the wholesome air which is the essence of any new century in architecture. In general I can say that I have never been in a city where the level is so high and so fresh.

I spent the day before in San Francisco, which is a somewhat larger and much older city and has had a long history – what with Maybeck and all – of great architecture. But in relation to what is being done now, in the past three years at least, this is better.

You are newer; you aren’t tied down by the traditions of San Francisco, which seems to be rather stuck with ordinary windows and ordinary walls. You do share the wood tradition, the great Maybeck tradition of using large enough wood so you can see it, unlike the Easterners who seem to prefer to use ¾-inch-thick boards or plywood. You do have that in common with California but I think you use it fresher and I think you mix it more with the strains that come from other parts of the world without fear for the future. But tonight I am not going to talk about the future. I am very interested in Frank Lloyd Wright and would like to say a few things which have been on my mind for quite some time. I’ve known Mr. Wright for a number of years. I know he is still alive and I thought therefore that this in a sense is the right time to speak out because, were he dead, that old maxim of “nothing about the dead, but the good” would tie my mouth – and I don’t want to wait until that time and have to make only pleasant statements.

Philip Johnson, by Carl Van Vechten, April 10, 1963.

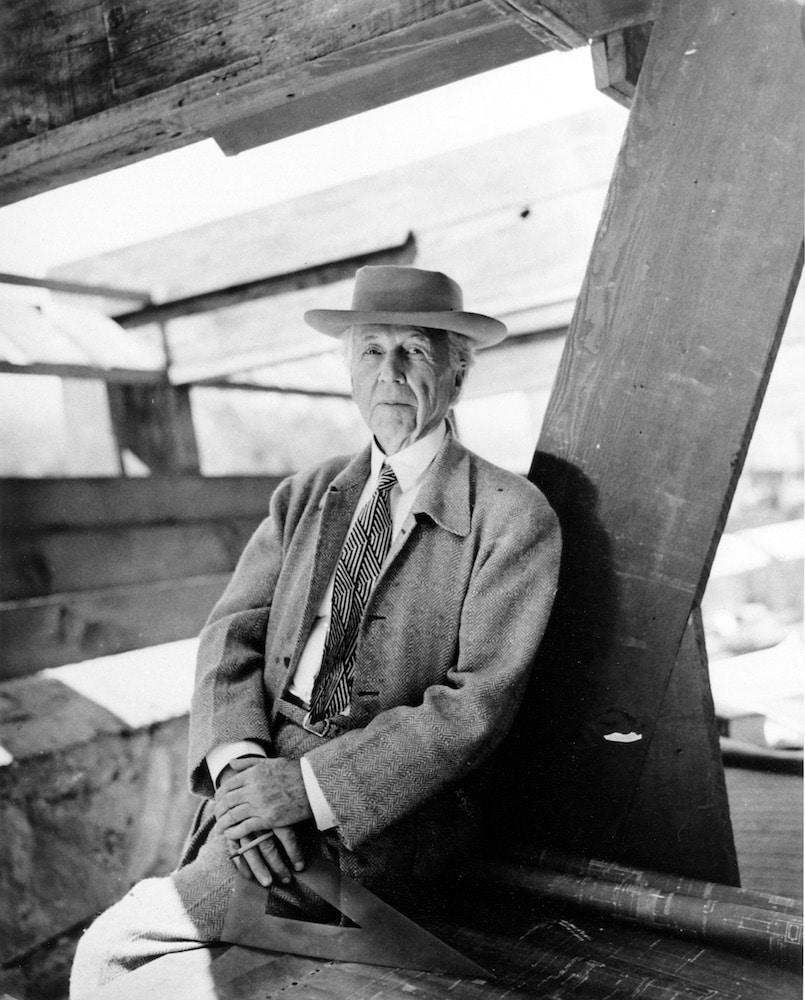

Portrait of Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West.

Mr. Wright has been annoying me for some time. (I didn’t say that he wasn’t a great architect).

He says that my house, especially the Glass House that you may have seen pictures of, is not a house at all – it’s not a shelter, it doesn’t have any caves, it’s cold and it doesn’t give you a feeling of comfort; it’s a box. He once said (he’s much cleverer, of course, than all the rest of us so you can’t say these things as well as he does) that my house is a monkey cage for a monkey. Then he came to my house the other day, strode in and said, “Philip, should I take off my hat or leave it on? Am I indoors or am I out?”

I don’t hope to keep up to him in anecdotes but I claim that it is a perfectly beautiful house to live in. And I would like to counter with a few remarks about some of his recent houses. I claim that they lack a lot of other things that are very valuable for living: they lack elegance completely, they lack all sense of clarity, they are confused in design, they have no consistency structurally. In the last house he did down our way, he was going around so many corners that he didn’t have time to hold up the beams, so he said to the boys, “We’ll put a Lally column there.” Unfortunately it happened to be in the living room.

He makes the strangest use of materials. He will combine cinder blocks, to which he has now taken a fancy, with mahogany: the roofs, the facias are all mahogany, the decorations all copper, but the house is made of cinder block, an awfully unpleasant material in the evening with a silk dress.

Mr. Wright has been annoying me for some time. (I didn’t say that he wasn’t a great architect).

Then there’s his open plan. I like open plans too but then I’m a bachelor, I can stand it. He opened the plan so far on this last house that the clients had to get rid of him and put the wall in between the living room and their bedroom because the children woke them up in the morning. So I think I can say that all these things are very bad.

The worst thing I ever said about Mr. Wright was that he was the greatest architect of the 19th century. I thought it was a compliment but in a way if you think back, the houses that I’m speaking of are the recent ones. Think back, for instance, to the great Riverside Club of 1900: the clarity is there, the elegance is there, and only one material is used in the entire project. The great, brooding, shingle hip roof chat became his mark at that time was extremely dignified and very clear structurally.

Then I’m annoyed by Mr. Wright’s talking a good deal. He uses words in an unusual way. For example, he talks about cities thus, “Cities are vampires living off the blood of the countryside and the villages, sterilizing humanity.”

Then he says that skyscrapers are “mollusks.” This is wonderful prose, pure 19th-century prose – “the mollusks erected for the exploitation of the man in the street.”

He can have his opinions. Whitman had them; Thoreau had them. There’s a quite good American tradition for having a hatred of the cities. But then why, in light of these remarks, does he intend to build the tallest, the largest and the most inhuman skyscraper in the world if he could (fortunately he cannot) in Chicago?

I find very annoying too his contempt for the history books, for all architecture that preceded him. Was he born full-blown from the head of Zeus chat he could be the only architect chat ever lived or ever will? I find it an undignified approach of our greatest living architect to talk about Michelangelo who, he says, created the greatest mistake of any architect that ever lived by building St. Peter’s dome.

Then almost worse is the contempt for the people who are going to come after him – and this is where it hurts us most, we slightly younger, older architects. He is determined that there shall not be any architect after him. Have you ever heard him talk about his own disciples, those poor children who sweat over the garbage pails at Taliesin East and Taliesin West year in and year out? Have you ever visited that place; and I am second to none in those who admire his architecture in those two houses, but he treats them like slaves.

Historic photo of Taliesin West Fellows breaking ground in the desert

I don’t think there are any of us who can deny his position. I wonder if all of us realize exactly what we do get, and I mean from the earlier Wright naturally, in all our work. I wonder if we realize what it would have been had he not changed the course of architecture single-handed from 1900 to 1910. It was he, don’t forget, who made roofs, walls, wainscoting and floor all independent of each other – independent elements of design.

But there is a gap which I still mean to point out and to me that happened in the architectural revolution of 1923, the internationalization of design which was based very much on Frank Lloyd Wright’s own work. Of course I speak of the pioneers like Gropius and Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe who independently, after the First World War, came to a type of design which gradually has spread over the entire Western world. It was a great deal of synthesized Wright. The elements were Wrightian but they were something more: they regarded the structural elements more than Wright ever did or still does.

Mr. Wright is very careless about how his buildings are held up once he has the way of looking at them settled. We would not dare – even his admirers – to build a building as casually as he does. Fortunately his son-in-law is an excellent engineer and will see to it afterwards that there is enough steel put into the wood in houses to insure the cantilevers from drooping too much-but they still droop.

I wonder if we realize what it would have been had he not changed the course of architecture single-handed from 1900 to 1910. It was he, don’t forget, who made roofs, walls, wainscoting and floor all independent of each other – independent elements of design.

However, Mr. Wright is cavalier about that. The younger men coming along in 1923 were not cavalier about that. Mies, of course, is the most extreme. He insists that structure is the element, the essence of architecture, and the arrangement of the elements within that frame – to him steel, of course, since it is the most American material – is what architecture is all about. He takes a very strong stand against Wright’s romanticism and I think that that has had an effect on every one of us; it has had its effect right here in the Northwest in spite of the much stronger influence of Wright here than anywhere else in the country.

Where are we now standing at this 100-year point? We ought to be standing at the threshold of the greatest architectural period in history; everything conspires to it. We have more buildings than the world has ever seen in a shorter time, more square feet. We have more money than any culture ever had at any time, within such a short time. We certainly have the architects.

Do we then have the principles that any of us can read in history books? Are we really convinced that right now are being designed the Taj Mahal, the Parthenon, the Chartres Cathedral? I don’t think any of us will claim that we are in any such period, and yet what elements are lacking?

There is only one lack and that is that there is no will in our culture to build; there is no desire in our culture that building be of any great importance.

Frank Lloyd Wright portrait at Taliesin West by Ralph Crane.

Where did we get off the track, as I believe we are? To me, it’s to be blamed on commercial committees, not on us. We don’t mind spending money; rather it’s the timidity of our culture in which we live, the setting up of dollar values for things which cannot be measured by dollars and cents-beauty. Our great corporate clients, or government clients for that matter, give nothing for beauty.

One wonders sometimes if architects will be necessary at all. Because of the economy, look what happens. If you build schools what do the school boards say? “How many dollars per student, how many dollars per square foot and how many square feet per student”? And what do you spend your time doing: cutting costs or building beautiful things? It is now becoming so that if you build a religious building, they will say, “How many dollars per pew?” How many dollars per square soul, perhaps, as a starter.

I think maybe that we, as architects who shouldn’t be, are getting a little bit influenced by the point of view of the world around us. We cannot be ivory-tower artists. We cannot sit it out if people don’t like our designs. We’ve got to go on building. We’ve got to go on because of our office, because of our children.

Do you think we ought to be quite so businesslike in our approach? We make our firms the way lawyers make theirs, not the way artists make firms. McKim, Mead, and White are all dead. It’s still a big firm because there’s value in it, a dollars and cents value in writing Stanford White’s name (he was shot in 1906), which is very strange – it’s the only country in the world where this happens; it is the only civilization in which this has ever happened.

Now there are, of course, some architects willing to starve and sit it out.

There is a man like Louis Kahn of Philadelphia, of whom it was said in the recent Harper’s magazine that if there is a genius in Philadelphia it’s Louis Kahn. He’s built one building there since the war. There is a man like Bruce Goff in Oklahoma. There is a man like Alexander Girard – all right, he doesn’t have an architectural degree; I’m afraid I don’t think that’s terribly important. I think that what’s important is how to mold space excitingly. Perhaps you have seen those magnificent colors he used to organize his own home in Santa Fe, N.M. Sure, that’s the only work he’s ever done but that doesn’t mean he’s not a great architect – well, let’s not use the word “architect”; let’s say “a shaper of space.”

Because, after all, what are we here for? One wonders exactly what is the purpose of being an architect? It surely isn’t only to put food in our mouths. There are other ways of doing that – a great deal easier and more remunerative.

Road to Taliesin West

Exterior view of Taliesin West near the Dining Room

But I wish to end with the same man I started with: a man that never gave up; the great American that perhaps we can admire at the same time we dislike him as much as I do – Frank Lloyd Wright. There is a man who creates space for its own sake and has never paid any attention to any other things.

Have you ever been to Taliesin in Arizona? I think that it is an experience which you can afford yourself. And I would plead with you to go before he is gone. He is 88; he is as brilliant and cantankerous and magnificent as ever. But the spirit will go out of the place when he is gone.

He has developed one thing which I will defy any of us to equal: the arrangements of secrets of space. I call it the hieratic aspects of architecture, the processional aspects. I would like to tell you about it briefly.

You drive up from Phoenix, about 20 miles out, up a dusty desert road, wondering why you came because it’s terribly hot, and you go up a slight rise. Finally you turn into a piece of particularly dusty, nasty and ill-kept road. But there is a little sign that says “Frank Lloyd Wright.” You come to a conglomeration of tents and stones where the car stops.

There is a low wall and you realize after you have been there and come back again, that he has been pushing out the spot where the car stops, further and further from his place. I’d like to recommend that to you and to me. The car, of course, is one of the deaths of architecture.

It’s out of scale, it makes noise, it doesn’t please the eye. And you cannot, from a sitting position, even look at architecture. It has to be by the actual use of the muscles of your feet.

He now makes you walk about 150 feet, until you get closer to this meaningless group of buildings. You’ve seen the plans many times and I’m sure you didn’t understand them any more than I did before I’d been there.

He calls it his “ship of the desert.” That’s where Frank Lloyd Wright is usually standing to greet you with his purple hair, his cape, and you say, “Now I’ve arrived at this magic place.” But you’ve just begun the trip.

As you approach, he starts you off on a slight slope, with the mountains to your left, and so up the first steps you go, away from the buildings instead of toward them. And how he takes your eyes and makes them follow. You go down the steps this way but the buildings are over there. Then the steps turn at right angles and you go between two low walls, very much narrower this time. You have the sensation that you are always changing your point of view on the buildings.

You turn, you pass his office, you climb four more steps and pass a great stone that he has put there with Indian hieroglyphics on it, which he found on his place. There is no door in sight. There is a tent roof on a stone base but no door; there is nothing in sight. You just begin to wonder.

Then the path takes you down a long walk, about 200 feet perhaps, with this tent room on your right, the mountains on your left.

You begin to wonder what is happening when, at your right, you pass the tent room, the building above goes on overhead. But the view separates – the two enormous piers – and you look again (a trick) through a dark room, a 6-foot room, out onto the terrace of Taliesin West: an enormous prow that sticks out over the mountains.

Now you’ve been climbing all this time and you never knew it because you never looked back; but for the first time, you realize you have been climbing and for 90 miles you look across the desert through that darkened hole. And again, of course, the steps start rippling. You go down three steps and then down three steps more and you are pulled out onto this prow of the desert.

He calls it his “ship of the desert.” That’s where Frank Lloyd Wright is usually standing to greet you with his purple hair, his cape, and you say, “Now I’ve arrived at this magic place.” But you’ve just begun the trip.

He then leads you through a gold-leaf concrete tunnel that turns three times and you are pushed out into the most single exciting room that we have in this country. It is indescribable except that you can say that the light, since it all comes from the tent above, has infiltered and mellowed.

Sitting Room at Taliesin West with steps at the end

You are just beginning to absorb this room when he opens a few of the tent flaps and this is when it really hits you. You look out – but not onto the desert. You look out this time on a little private secret garden that he has built beyond this room, where water is playing unlike any water in the desert. The plants are 20 feet high in this garden, and there is a lawn such as you have seen only in New England.

You say, “Now I see what I’ve come to Taliesin for”; you have not.

He makes one more turn, two more turns. This time the door is 18 inches wide and you have to go through sidewise. It is entirely an inside room, no desert or garden. One wall is of plants. To be sure, you cannot see them; that is, you can’t see through them, but that gives you the jungle light that comes into the room. There is a shaft of light that comes from 12 or 14 feet above (this is a very high room now). The room is 21 by 14 feet, all stone. One entire length of it is the fireplace; on the other long wall is a table and two chairs – and that is where you have come to be.

You sit down with Frank Lloyd Wright and he says, “Welcome to Taliesin.”

My friends, that is the essence of architecture.

Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West in 1958.