Monumental Women: Determined Women Delivered Historic Commissions to Frank Lloyd Wright

Ron McCrea | Mar 8, 2018

An exploration of the women who fueled the creation of some of Wright’s greatest spaces.

The baroness Hilla von Rebay had never seen a building by Frank Lloyd Wright when she reached out to him to design a museum for her patron, Solomon Guggenheim. But she had seen pictures of Wright’s work in Berlin and she knew he was the one to do it.

“I need a fighter, a lover of space, and originator, a tester and a wise man,” she wrote to Wright on June 1, 1943. “I want a temple of spirit, a monument! And your help to make it possible… may this wish be blessed.”

Wright charged at the opportunity. Fifteen days later there was a signed agreement, there was a payment in the bank, and the museum that would transform all museum-making was on its way. “In retrospect,” says Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer in The Guggenheim Correspondence (1986), “it was Hilla Rebay whose efforts on all fronts, initiated, propelled, and in truth inspired the building.”

Feisty, determined women like Hilla Rebay were responsible for a large portion of Wright’s completed work. How large a portion is not known, because the men who wrote the checks usually got the credit. But there is no dispute that women delivered to Wright the commissions for four civic projects: Jiyu Gakuen, “School of the Free Spirit” in Tokyo (1921); the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue in New York City (1946); the Marin County Civic Center in California (1957); and the Monona Terrace Civic Center in Madison, Wisconsin (1954). Monona Terrace was won by two “professors’ wives,” Mary Lescohier and Helen Groves, who delivered a trifecta of referendum votes, then lost due to the connivance of a male legislator and his cronies in the Capitol. But, even in defeat, Lescohier kept Wright’s vision on the public agenda long enough for it to be resurrected in a different form decades later by Madison’s mayor, Paul Soglin.

Women in Wright’s time were limited by gender both as professional architects and as clients for architecture. But Wright respected women. His first hire for his Oak Park studio in 1895 was Marion Mahony, one of the first women to receive a degree in architecture from M.I.T. Wright’s Wisconsin aunts, Ellen and Jane Lloyd-Jones, gave their nephew his first independent commission in 1887, the main building for Hillside Home School. Jane Addams, the great Chicago reformer, gave Wright the platform of Hull House in 1901 to deliver his famous lecture, “The Art and Craft of the Machine.” He was always in women’s debt.

They may have been held back as economic actors in the business world, but women could exert power in two areas that required an architect. One was the private residence, where Wright’s experiments found willing female collaborators including Susan Lawrence Dana, Alice Millard, Aline Barnsdall, Isabelle Martin, Della Walker, Dorothy Turkel, and Karen Johnson Boyd, to name a few. The other area in which women could exert power was civic and cultural institutions.

HANI MOTOKO: A SCHOOL FOR MODERN GIRLS

In 1921 Wright accepted the invitation from Hani Motoko to design a school for girls on a green campus in the heart of Tokyo—a school that, like his aunts’ Hillside, would break the traditional mold of education.

Motoko defied the Japanese cultural command that women fit the ideal of “Good Wife, Wise Mother.” Born in 1873, she was the granddaughter of a former Samurai, daughter of a lawyer, and a member in 1891 of the first graduating class of the Tokyo First Higher Girls’ School. Within six years she had broken barriers to become the first female newspaper reporter in Japan. In 1906 she and her second husband, Hani Yoshikazu, founded the long-running magazine Fujin no Tomo (Women’s Friend), of which she was editor and publisher.

Hani Motoko met Wright amid an exhilarating period of openness in Japan known as Taisho Freedom. Karen Severns, the producer with Koichi More of the documentary Magnificent Obsession: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Buildings and Legacy in Japan (2005), writes “The Taisho Era, 1912-1926, was one of great liberalism, and the ‘free education movement’ was part of the move to a more open, democratic society. The Hanis had founded the Fujin no Tomo magazine to help liberate housewives, and when their two daughters, Setsuko and Keiko, were school age, they wanted to make sure they would receive a more progressive education.”

Exterior view of Jiyu Gakuen.

Arata Endo, an architect and Wright’s chief assistant, presented the Hanis to Wright at the Imperial Hotel in mid-January, 1921. “Arata knew the Hanis because they all attended the Fujimicho Church in Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo which was known for its theological liberalism,” Severns says, adding that the Hanis’ granddaughter, Yuko Hani, later wrote of being told by her grandfather that “Wright and Motoko seemed to become instant friends, and would talk at length about the project.”

In February, Motoko announced the news of the new school in her magazine and announced that Wright would be the architect. Building proceeded quickly and on April 15, the Tokyo newspaper Asahi Shimbun reported the opening and quoted Motoko as saying, “One of the ideals of Jiyu Gakuen is to make its outward appearance simple and fill it with outstanding thoughts. It was an unexpected good fortune that while we were creating Jiyu Gakuen as frugally as possible under our limited resources, we were blessed with the tastes and thoughts of Mr. Wright, a world-famous building artist.”

Arata Endo shared credit for the designs and added buildings to the campus after Wright left Japan. “Considering the speed with which the designs were completed, it’s clear that Wright, Arata and the Hanis were in full accord and the stars were aligned,” Severns says. “Wright and Arata’s design for Jiyu Gakuen is the perfect embodiment of the school’s Christian spirit and its progressive education ideals, as well as an outward expression of the architect’s unshakable belief that a beautiful building nurtures the soul.”

“One can imagine that Wright found in the indomitable Hani Motoko strong parallels with his own aunts, Ellen and Jane. Madame Hani was also inspired by the philosophy of Emersonian self-reliance, and wanted to develop her students’ characters and creativity by having them learn through doing.”

Julia Meech, the author of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan (2001), calls Jiyu Gakuen “a small masterpiece” and notes, “Miraculously, this simple but elegant wood and mortar structure is still standing in the Mejiro section of Tokyo.” Hani Motoko died in 1957 at the age of 84. Her school fell into disrepair and nearly was demolished, like Wright’s Imperial Hotel, to make more intensive use of the air space in the heart of Tokyo. But in 1992 international alumni and Wright admirers rallied to win government help to preserve the historic campus. Today it serves ceremonial functions, receives tour and alumni groups and hosts wedding receptions.

The school’s educational work continues on a separate campus. “It still hews to the same principles, with most aspects of school life run by student committees,” The New York Times reports. “The school has thus been a magnet for free spirits and artists. Its graduates include many film directors and musicians. Yoko Ono, the avant-garde performer and widow of the former Beatle John Lennon, attended the kindergarten, as did Ryuichi Sakamoto, a composer known for his musical score for the movie ‘The Last Emperor.’

VERA SCHULTZ: A CIVIC CENTER FOR MARIN

Vera Lucille Smith Schultz, the Northern California county supervisor who decided Wright should be the architect of the Marin County Civic Center—at the cost of her political career—came from a line of very tough women.

Her grandmother, Hannah Klingensmith, set out on her own with her 15 children in the 1860s after Brigham Young ordered her husband, a Mormon bishop, to take a second wife. She cut her ties to the church and homesteaded a ranch in Dutch Flats, Nevada. Two of her boys, twin sons, married and had eight children apiece. Vera was the youngest of one of them, John Henry, in 1902. When her father died of a gunshot wound inflicted accidentally by his twin brother in the gold-rush town of Tonopa, Nevada. Vera’s mother opened a boarding house. “I cut my teeth on Democratic Party politics at my mother’s table,” Vera said. “I learned that the rich squeeze the poor, and the wage-earner has nowhere to turn but the government.”

This dedicated New Dealer went on to become the first woman to be elected to the Board of Supervisors of the most Republican county in California, Marin. Schultz’s secret of success was to be an activist for good government who could get things done. As Evelyn Radford writes in her biography, Vera: First Lady of Marin (1998), “Vera was the model citizen, the model activist, the model politician. Since her death she has become almost heroic in stature in the county she loved so much.”

Vera Schultz

But before she was a hero, she was a lightning rod for Frank Lloyd Wright. In the postwar years, as Marin County grew in affluence and importance as a bedroom suburb of San Francisco, the demand for modern government services grew with it. County offices were scattered in more than a dozen locations. When an 80-acre site near the Golden Gate Bridge became available, the search for an architect of a one-stop courts and county government center began.

Several local architects were considered, including Richard Neutra, who originally came to California in the 1920s to work with Wright. Vera Schultz found the model Neutra presented to be too stark for her tastes. Then, on New Year’s Day, 1957, she found herself reading an issue of House Beautiful that carried an article on new Wright designs and their impact on other architects. (The editor of House Beautiful, Elizabeth Gordon, had become a crusader for Wright and organic architecture, and had hired John DeKoven Hill, a Taliesin apprentice, to be her architecture editor.) Suddenly inspired, she called her friend, Mary Summers, the chair of the Planning Commission. “Mary!” she exclaimed, “Why can’t we have the best? Why can’t we have Frank Lloyd Wright for our building?”

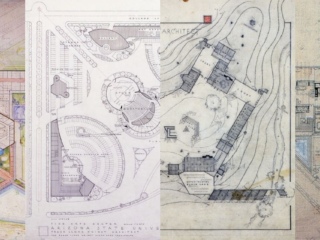

Marin County Civic Center

Summers embraced the idea, and Schultz wrote a letter to Wright at Talieisn West outlining the county’s needs and inviting him to visit. Wright, then 89, played hard to get. He insisted on the Civic Center Committee coming to him at his San Francisco office, run by Aaron Green. He also let it be known that he would not compete with other architects for the commission. Mary Summers quickly dispensed with the other candidates. On June 27, the board voted 4-1 to open negotiations with Wright.

Wright’s presentation of his plan and the signing of the contract were set for the morning of Saturday, June 29 at the San Rafael High School auditorium. When Wright arrived and before the meeting could begin, he and the board were ambushed by a group of organized opponents, veterans from the American Legion and a newly revived Taxpayer Alliance, who came hoping to torpedo the project in front of the crowd of 700. The county clerk who was in cahoots and had “lost” the contact, began to read a seven-page letter from the veterans accusing Wright of being a Communist sympathizer and subversive who had promoted draft resistance during World War II.

Wright, nonplussed, jumped to his feet and shook his cane. “Aw, rats, take me as I am or not all,” he said, Green recalled in An Architect for Democracy (1990), which he dedicated to Shultz and Summers. “This is an absolute and utter insult and I will not be subjected to it!” Outside, he told reporters, “I don’t have to listen to this rot. There’s no substance in that. I am a loyal American citizen. Look at the record.”

Wesley Peters, Aaron Green, Mary Summers, and Vera Schultz

Inside the hall, Radford writes, “Vera bounded out of her chair, furiously demanding an apology [from the Legion ringleader]. He had humiliated the whole county, she cried.”

Mary Summers prevailed on Wright to go to lunch with the board, and afterward they visited the building site.

“After only twenty minutes on the site, Frank Lloyd Wright decided on his design concept for the Marin County Civic Center,” Green remembered. “‘I’ll bridge these hills with graceful arches,’ he said to me as he described an arc in the air with his hands. The gesture seemed to conjure up his architecture as a reality.”

The Civic Center was built, but Wright did not live to see it. He died on April 9, 1959, nearly a year before the groundbreaking. Green and a team of Taliesin architects led the projects to completion. Olgivanna Lloyd Wright chose the blue roof.

Just before the county elections of June, 1960, tax bills were delivered that shocked voters in Vera Schultz’s district. A property reassessment, the first since the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge, had doubled and even tripled rates. “Suddenly in Southern Marin, the Civic Center became the ‘Taj Mahal’ and was blamed for the whole tax increase,” Radford writes. Schultz was voted out of office and never held elective office again.

She died on May 9, 1995. The Marin Independent Journal’s editorial tribute said: “So relentlessly did Vera Schultz dare to dream—and so lasting is her legacy—that its hard to believe she’s gone now, at 92. Marin is richer today because Vera Schultz never stopped believing in tomorrow—and in herself.”

MARY LESCOHIER, HELEN GROVES, AND MONONA TERRACE

One of the opponents who came to California to red-bait Wright, hoping to torpedo the Marin County Civic Center, was an old adversary form Madison, Wisconsin: attorney, city alderman and Republican State Rep. Carroll Metzner. Metzner despised Wright’s politics, questions his patriotism, and accused him of playing fast and loose with public funds and budgets. When he came to Marin in June 1957, he was fresh from victory in his last-ditch effort to stop Madison from building a Wright-designed civic center on the downtown shore of Lake Monona. City voters had approved it but state Legislature had effectively outlawed it, using a tactic Metzner had devised in mid-April.

Leading the charge for Wright’s Monona Terrace has been two intrepid women, Helen Groves and Mary Lescohier, both 53. Groves, a Quaker who had organized “stone-haulers” to build Wright’s first Unitarian Society Meeting House in 1951 but had never been involved in local politics, was captivated by his vision of a building that would “marry the city to beautiful Lake Monona” when she heard him speak to a local government audience in 1953. She conducted a poll of her neighbors and found strong support for Wright’s plan, and also for a public referendum to advance it. Her husband, Harold Groves, a noted economist and co-author of Wisconsin’s first-in-the-nation unemployment compensation law, suggested she team up with Mary Lescohier, who had more tactical and political experience.

Mary Lescoheir and Geraldine Nestingen

During the Depression Loscohier had coordinated a relief effort in West Virginia for the American Friends Service Committee and had met Eleanor Roosevelt, who persuaded her to campaign for her husband in New York. According to David Mollenhoff and Mary Jane Hamilton in their authoritative book Frank Lloyd Wright’s Monona Terrace: The Enduring Power of a Civic Vision (1999), “she crisscrossed souther New York State in a motor caravan. She coordinated speakers and even made direct appeals to voters on street corners with a bullhorn.” After meeting her husband Don, a labor economist, in a New Deal project, they came to Madison and she became the editor in 1942 of the journal of Land Economics.

Monona Terrace. Photo by Robert Farrell.

When Helen Groves approached her, “Lescohier threw her heart and soul into the Monona Terrace Crusade. She recruited her friends and colleagues, testified at city and county meetings, wrote press releases, spent hours on the telephone, and ran a mimeograph machine,” Mollenhoff and Hamilton write. “Because of her keen intelligence, sharp tongue, powerful writing, and acute sense of strategy, Lescohier was formidable proponent of Monona Terrace.” Frank Lloyd Wright fondly called her “Little Sister.”

When the city fathers and the Madison Common Council balked at letting the people have a say, Lescohier and Groves called a meeting of 50 supporters who formed Citizens for Monona Terrace and began to circulate petitions compelling the city to hold a binding referendum. “To succeed they had to gather signatures from 6,800 voters by September 8, just 36 days away,” Mollenhoff and Hamilton note, and four days before the deadline, the women were still 3,000 signatures short. They redoubled their efforts with 150 volunteers. “At 4:35 p.m., five minutes after the official closing time, Lescohier and Groves delivered to the city clerk a bundle of petitions bearing 6,900 signatures, 100 more than they needed.”

The election was held on November 2, 1954. The Madison ballot had three separate questions, one to authorize up to $4 million in bonding for an auditorium and civic center; the second, to designate Frank Lloyd Wright as the architect; and third, to select the Monona terrace site.

All three questions won their “yes” votes. The appropriation won with 79 percent of the vote. Wright won the 52 percent, and the site won with 59 percent. He was the people’s choice. “Wright was thrilled,” Mollenhoff and Hamilton write. “To him it was a grand ‘democratic gesture,’ and ‘the only one I know of in America where the architect was chosen by the people.’”

“Conservatives were stunned,” the authors report. “Two women with almost no political experience, completely outside the power structure, armed with little more than an idea, a packed of architect’s renderings, and Wright’s promise of a building that would create a ‘greater and more noble Madison,’ had persuaded hundreds of citizens to enlist in their grassroots army, successfully hijacked a coalition of Madison’s most powerful leaders, and elected Wright as the architect. And they did it with campaign expenses totaling $261.51.”

But the people’s will would be thwarted. Monona Terrace would be blocked by a state law designed only for that purpose. It would not be built for more than 40 years, and Wright would not live to see it.

In 1957m while Marin was moving forward, the Republican-dominated Wisconsin Legislature approved a bill (by just one vote in the Senate) written by Metzner that limited the height of buildings along Madison’s dock line to “no more than 20 feet.” The Metzner Law, as it was known, halted Monona Terrace. It was repealed in 1959, just weeks before Wright died. But by then, the money previously approved was too little to build the project. Another referendum was held in 1962, and Monona Terrace lost by 54 percent.

“Lescohier died in 1984 believing that her work on behalf of Monona Terrace had been futile,” Mollenhoff and Hamilton write, “But it was not her efforts, along with those of a handful of other civic leaders, kept Monona Terrace on the civic marquee for more than 20 years… Had she lived to see her great dream realized, she would have been quick to deflect credit to others. In truth, much credit is hers.”

Helen Groves outlived Mary by 10 years. She died before construction began of today’s Monona Terrace Community and Convention Center, which adapts Wright’s plan to a design by Talieisn architect Tony Puttnam. When she learned in the early 1990s that Monona Terrace might be at last resurrected by Mayor Paul Soglin, her biographers say, Helen Groves offered to organize support among the residents of her nursing home.

HILLA REBAY: SOLOMON GUGGENHEIM’S GURU

Born in Strasbourg in 1890 to a Prussian military officer and his wife, the woman who drove New York’s Guggenheim Museum into reality was named Hildegard Anna Augusta Elizabeth Freiin Rebay von Ehrenwiesen, Baroness Hilla von Rebay. But when she became an American citizen she dropped it all and became simply Hilla Rebay.

Frank Lloyd Wright thought she was a man when she wrote him on June 1, 1943, asking whether he might design “a building for our collection of non-objective paintings.” He immediately invited “Mr. Rebay” to “run down here for a weekend” to Taliesin and “bring your wife.”

She explained in reply, “Mr. Guggenheim is 82 years old and we have no time to lose.” As a German national she was also under wartime travel restrictions. “Please come to New York. You have to see this collection to realize the great work done and greater to come. I know what is needed. Nothing that is heavy but organic, refined, sensitive to space most of all. I am not a man, but I built up this collection, this foundation, and we have a small gallery in a rented house…”

“We” meant Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim, heir to the Swiss family’s mining fortune, former owner of a gold mining company in the Yukon, and now a serious collector of modern art. He had come under the spell of Hilla Rebay in 1928 when she painted his portrait and told him of the spiritual wonders of pure, “non-objective” art as practiced by Wassily Kadinsky, Rudolf Bauer, and others.

Rebay, an accomplished painter herself, had already created a Museum of Non-Objective Painting in two locations for Guggenheim’s growing collection, which he had purchased with her serving as his adviser, curator, and confidante. The collection grew faster after he saw her friends’ work appear in Hitler’s exhibit of “Degenerate Art” in Munich in 1937. Hans Richter, a German artist and New York filmmaker, wrote that Guggenheim had decided in 1939 “to evacuate from endangered Europe all important works from all periods, especially those of the last generation that are loaded with the future, to bring them to America and plant the ‘seed of culture’ directly into America’s soil.” Rebay and Guggenheim also helped endangered Jewish artists flee the Nazis. She was held in suspicion by both the Gestapo and the FBI.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hilla Rebay, and Solomon R. Guggenheim viewing model, 1946.

When it came time to build a big museum and choose an architect, Rebay briefly considered Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius before choosing Wright. She remembered Wright after seeing his traveling exhibition in Berlin in 1931 and after talking to his admirer, architect Erich Mendelsohn. To Wright she wrote, “I have never seen a building you have made, but [I have seen] photos, and I feel them—while I never felt others’ work as much.”

Bruce Pfeiffer reports that at their first New York meeting, Rebay and Wright “liked one another instantly, and an abiding affection took root between them that would cushion those bitter conflicts that lay ahead. Very soon they were on a first-name basis, and her vigorous personality was such that she got not only Mr. Wright but Mrs. Wright to share in her medical idiosyncrasies.” That meant blood-letting with leeches, and in the case of Wright, having all his teeth pulled and replaced with dentures, all “within six weeks of their acquaintance.” The sacrifices might have been a measure of how desperately Wright needed the Guggenheim commission. But he also understood his promise. In a December letter urging Rebay to settle on a building site, he said, “I am so full of ideas for our museum that I am likely to blow up or commit suicide beofre I can let them out on paper.”

Some ideas went nowhere. She wanted a theater that could allow artists to project mechanized light shows on the ceiling. That never happened. He designed private apartments for both Rebay and Guggenheim in the Monitor tower of the Fifth Avenue museum. Those plans were scrapped for offices and storage. Wright suggested that red might be a good color for the building. Rebay must have exploded, because he quickly retreated. “I probably shouldn’t have said anything about color, as Form comes first in importance in Architecture,” he said. “Certainly I don’t mean red as you have it in mind but mean rose with white veins.” He apparently was thinking of rose marble, and he did send her marble samples. But, “we can imagine any color, no matter what color the sketches show, that appeals to you.”

The creation of the Guggenheim turned out to be a 16-year struggle, longer than anyone imagined. Wright submitted six separate sets of plans and 749 drawings. There were numerous disputes and delays, and New York artists protested Wright’s plan to hang paintings on curved walls. The design was mocked as resembling a washing machine or a toilet bowl. Wright made good on his promise to Solomon Guggenheim that his modern museum would “make the Metropolitan Museum look like a Protestant barn.”

Guggenheim’s death in 1949 changed everything. Rebay was forced out as the museum’s director in 1952. She was removed as a Guggenheim Foundation trustee by the other family members, who referred to her as “the B” —the B not standing for baroness. The new director, James Johnson Sweeney, made changes in Wright’s plan that left the architect dismayed, and Harry Guggenheim, who became foundation president, was unsympathetic. (His wife, Newsday publisher Alicia Patterson, became a lifelong friend of the Wrights.)

The museum made amends to Rebay in 2005 by mounting the first major retrospective of her work in New York and Munich, and by publishing a lavish catalog with essays, The Art of Tomorrow: Hilla Rebay and Solomon R. Guggenheim.

Unlike the other U.S. commissions for which women served as midwives—the Marin County Civic Center and Monona Terrace—Wright did live to see his Midtown marvel taking final form. He died six months before the opening ceremony, which was held at noon on October 21, 1959. Of the three figures who created the Guggenheim Museum, two were gone, Frank Lloyd Wright and Solomon R. Guggenheim. The third founder, Hilla Rebay, was alive and well. She was not invited.

The Guggenheim Museum under construction.

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2015 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, “Building with Brick.”

Ron McCrea, author of Building Taliesin: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home of Love and Loss (2012), is writing a book on women’s contributions to Wright’s life and career.