Frank Lloyd Wright’s Lasting Architectural Influence

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Feb 11, 2020

Frank Lloyd Wright’s signature style and ongoing influence have long inspired architecture around the globe, and continues to today. In the current issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine, “UNESCO World Heritage: The 20th Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright,” Foundation President & CEO, Stuart Graff, shares more about this influence.

When observing architecture of today, it’s easy to spot and identify ways in which Frank Lloyd Wright’s design principles and work may have inspired the structures. For example, even to the casual observer, the influence of Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York can be seen in many modern designs. Recent articles on Dezeen demonstrated this influence in Kengo Kuma’s The Exchange in Australia and Tadao Ando’s He Museum in China.

The materials used, unit systems, and harmony between the structures and the environment seen in these examples make a clear connection with Wright’s design principles. This ever-present influence on architecture decades after Wright’s passing is also a testament to the timelessness of his designs and ideas.

In the winter 2020 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine, “UNESCO World Heritage: The 20th Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright,” Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation President & CEO Stuart Graff speaks to this influence in his article, “The Work Shall Grow.” The following is an excerpt from the article. Become a member of the Foundation to receive future Quarterly issues.

Kengo Kuma’s The Exchange, photo by Martin Mischkulnig / Header image by Martin Mischkulnig

Wright’s Influence Today

In contemporary architecture, we see Wright’s influence manifested not so much through his forms, but through Wright’s ideas. No doubt, this would have pleased the man who rejected imitative work by his apprentices, from whom he preferred original expressions of organic architecture. It is satisfying to observe that, in an age when much of contemporary architecture values the banal, the obscure, and the outrageous, the core values of organicity still define the work of great masters. They are world-renowned and known only locally; they build monumental works and private homes; they have established reputations or are just now making them.

While experts may disagree, I find Wright’s ideas represented in the works of these architects, among others:

- Kengo Kuma, the great contemporary Japanese architect, visited Taliesin and Taliesin West in 2018, where he described how the Japanese print—the source of so much of Wright’s compositional technique—deeply influences his own work which fully embraces the organic qualities initiated in Wright’s principles.

- Zaha Hadid created stunning, flowing forms where space and structure evolved with continuity and grace, embodying Wright’s poetry of space as “the continual becoming: invisible foundation from which all rhythms flow to which they must pass.”

Kengo Kuma, Portland Japanese Garden Cultural Village. Photo by Bruce Forster.

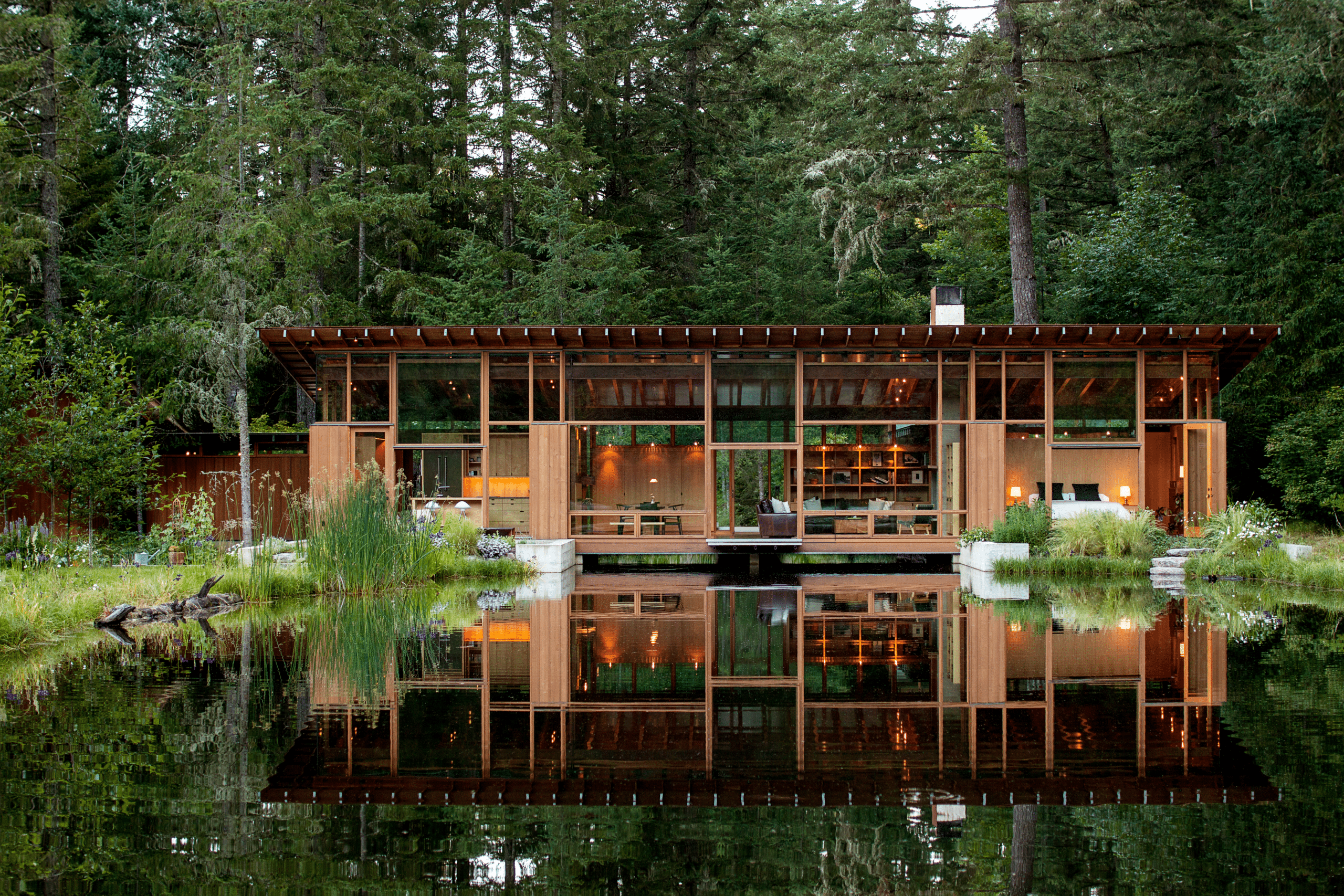

Cutler Anderson Architects, Newberg Residence. Photo by Jeremy Bittermann.

- Yasuhisa Toyota’s acoustic panels—all 10,000 unique structures—embrace specialization and organic response achieved through parametric modeling to create a rich aural environment in Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie—while also creating a visual aesthetic that seems drawn for nature.

- The work of Cutler Anderson architects—and particularly their private homes— succeeds through its connectedness to the surrounding environment as a result of visual, structural, and material cues.

We often see Wright’s works cited as early exemplars of sustainable architecture, and no doubt his sense of interconnectedness between building, landscape, and activity were at work in the same way that ecosystems develop and become sustaining. And though his solar-hemicycles, clerestories, translucent roofs, and site-specific designs promoted efficient use of energy, natural light, and openness to the elements, it’s fair to say that his work suggested a path toward sustainability as we use that term today, rather than the direct embrace of sustainable principles.

More significant is Wright’s understanding and use of structure and materials from nature—biomimicry. Most famously, Wright looked to the fibrous skeleton of the modest staghorn cholla cactus to create the steel latticework that would allow the columns of the SC Johnson Administration Building to stand. Today, at a macro level, we experience biomimetic design in works that derive from the temperature self-regulation characteristics of saguaro cacti to create energy efficient homes in Phoenix, or the inspiration of sea sponges to establish the structural resilience of an office tower in London.

Wright’s work also seemed to respect our cognitive experience of the world, even if he didn’t necessarily have the science to inform his designs and could rely only upon what he observed for himself. As Sarah Williams Goldhagen observed in her outstanding summary of research on the intersection of cognition and the built environment, science has “confirmed what Wright intuited [in his design of the Hanna House]: human spatial navigation is organized around our practice of nonconsciously, imaginatively triangulating the location of our body in space with two other proximate points, in order to help us find our way.”

You can read the rest of Stuart Graff’s article as well as more insights on Wright’s everlasting architectural influence in the winter 2020 Quarterly, “UNESCO World Heritage: The 20th Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.”

Swipe through the photos below to see if you can identify any similarities between Wright’s Guggenheim Museum and Kengo Kuma’s The Exchange and Tadao Ando’s He Museum.

1. Tadao Ando Architect & Associates 3. Photo by Martin Mischkulnig 4. Tadao Ando Architect & Associates 5. Photo by David Heald

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation members receive the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine as part of their membership benefits. In this special winter 2020 issue of the Quarterly, “UNESCO World Heritage: The 20th Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright,” we celebrate the recent inscription by sharing personal reflections from stewards of each of the eight sites.