Concerning the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Frank Lloyd Wright | Oct 21, 2019

When Frank Lloyd Wright designed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, he was compelled by what he believed the building could be. 60 years after the museum first opened, we reflect on Wright’s persistence, passion, and vision that made this architectural icon possible.

On October 21, 1959, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum opened its doors, nearly 17 years after Hilla Rebay, Solomon R. Guggenheim’s art advisor and director of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, wrote to Frank Lloyd Wright looking for a “fighter, a lover of space, an originator, a tester and a wise man,” to design “a temple of spirit, a monument” as a space to display Guggenheim’s art collection. Wright wrote back, affirming Rebay’s enthusiasm, and expressing confidence in his ability to design a space worthy of the expectations she described.

Their ideas and confidence would later be tested through the tumultuous years leading up to the opening of the iconic space. Plenty of battles were fought to keep the spirit of the museum alive. From firings to criticisms, design after design of the museum (a total of 749 drawings were made) were presented and challenged. Wright was compelled by what he believed the building could be, and because of his persistence, passion, and vision, how we build and live was changed forever. Now, 60 years later, we look back on this spark that kept the museum moving forward.

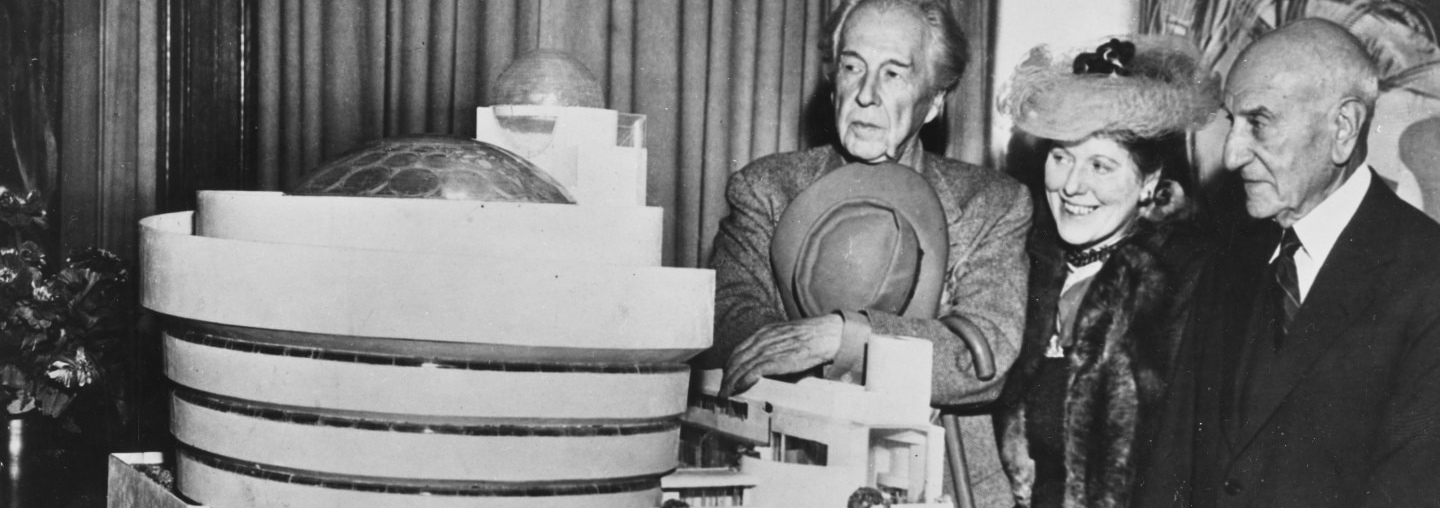

Header Image: Frank Lloyd Wright, Hilla Rebay, and Solomon R. Guggenheim, 1945. © Donald Greenhaus; Above: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in construction, 1958.

DECEMBER 14, 1957

CONCERNING THE SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM

I don’t know who alerted and alarmed our conscientious objectors—these signatory painters—but their signatures do them and their curators no credit.

I might as well tell the truth. Here it is: Solomon R. Guggenheim, benefactor behind their ungrateful rumpus, was to me and to many, a remarkably keen, bold patron of the kind of painting to be believed in— painting in itself, like music, not confined to featured conformity to natural objects, but exploiting line, color and rhythm in themselves according to the spirit of more sentient human-beings.

There was no good place in which to show painting of this free nature. Museums as they stood would deny the new freedom by the conventional, static manner in which it would there have to be immured. So Mr. Guggenheim called upon me to help—provide suitable environment in circumstances appropriate to display Art with a capital “A” to best advantage—often repeating—“I do not want to leave to my city just another museum.”

I could see good reason for his point of view and eventually presented him with the controversial scheme of arrangement for showing free-painting, freely, in a free atmosphere. Unfortunately, before our good donor died he was unable to see his museum built because of all kinds of local fear and prejudice. However, three months before he died, knowing he was dying he called me to him and said, “Mr. Wright, can you build our museum as we have worked on it together all these years (seven) for two million dollars—without fees?”

“Yes, Mr. Guggenheim. If you will allow me to make the changes I have suggested, I will promise.”

I did not know he was so ill—but three months later he died. His will read, there provided was two million dollars to his trustees to build his kind of museum. It would now be his memorial. Believing in Mr. Guggenheim’s vision of a better kind of museum for greater freedom in Art, admiring his perspicacity, fortitude and generosity, I kept on for five years more faithfully trying to get this prophecy of his built. Delays kept on while costs kept rising. Finally in spite of all delays the trustees let the contract for about three million dollars for the kind of museum the donor wanted built. But now it is to be built upon the entire block-frontage instead of the three-quarters we originally had to work with. The trustees stood back of and bettered his desire for “not just another museum.”

Now this farsighted (as it will prove) bequest of this bold modern Florentine-de-Medici—or greater because the American envisioned a future whereas they only preserved a present order—should be respected as I believe it has been by the Guggenheim trustees and myself.

If Mr. Guggenheim was wrong about this new way of showing his pictures—and certain conventional artists and their curators do know, more than we, what his museum should be all about—I suggest that even so, every fair chance be due to prove him right.

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum is a great gift to humanity. How great will be seen. I believe him right because what he wanted was natural. The fact that the whole affair of showing paintings had become unnatural—more and more a picture-dealer’s artificiality—accounts for the enslavement of art to the categorical imperative of the professional expert. But by no means should “static” nullify this generous man’s intelligent bequest, so beneficial to the very folk now ignorantly looking the gift-horse in the teeth. I believe there is more in heaven and on earth than these Horatios dream in their philosophy. T’would be shame now to take such at their word.

This letter originally appeared in the summer 2019 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine, “Standing Out in a Crowd: 60 Years of the Guggenheim.”