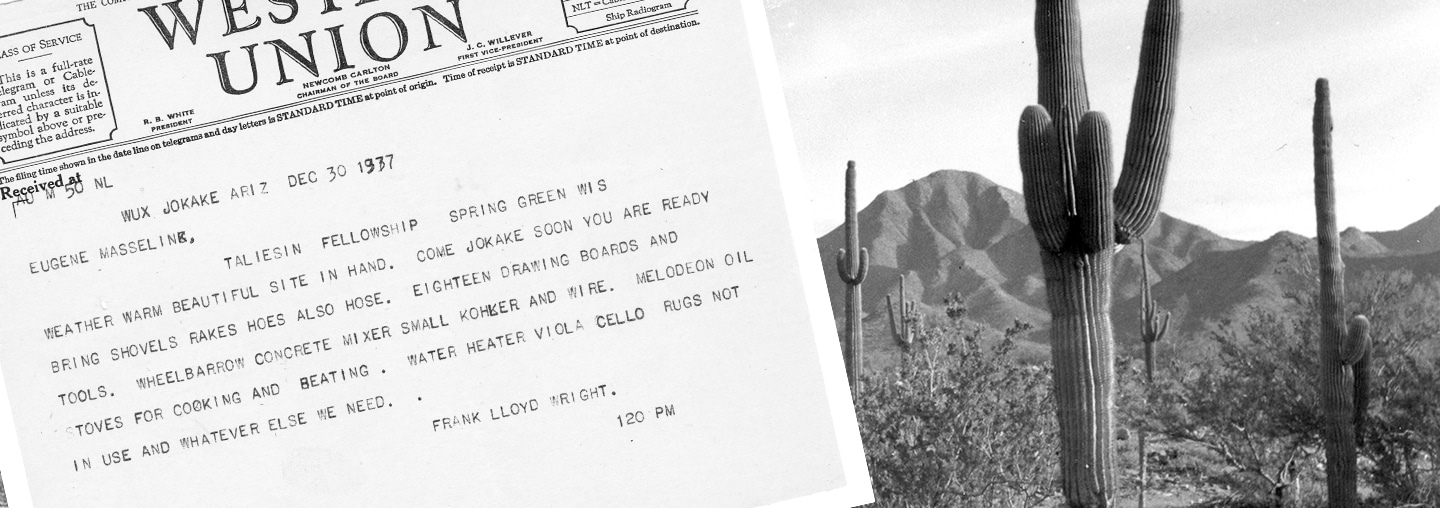

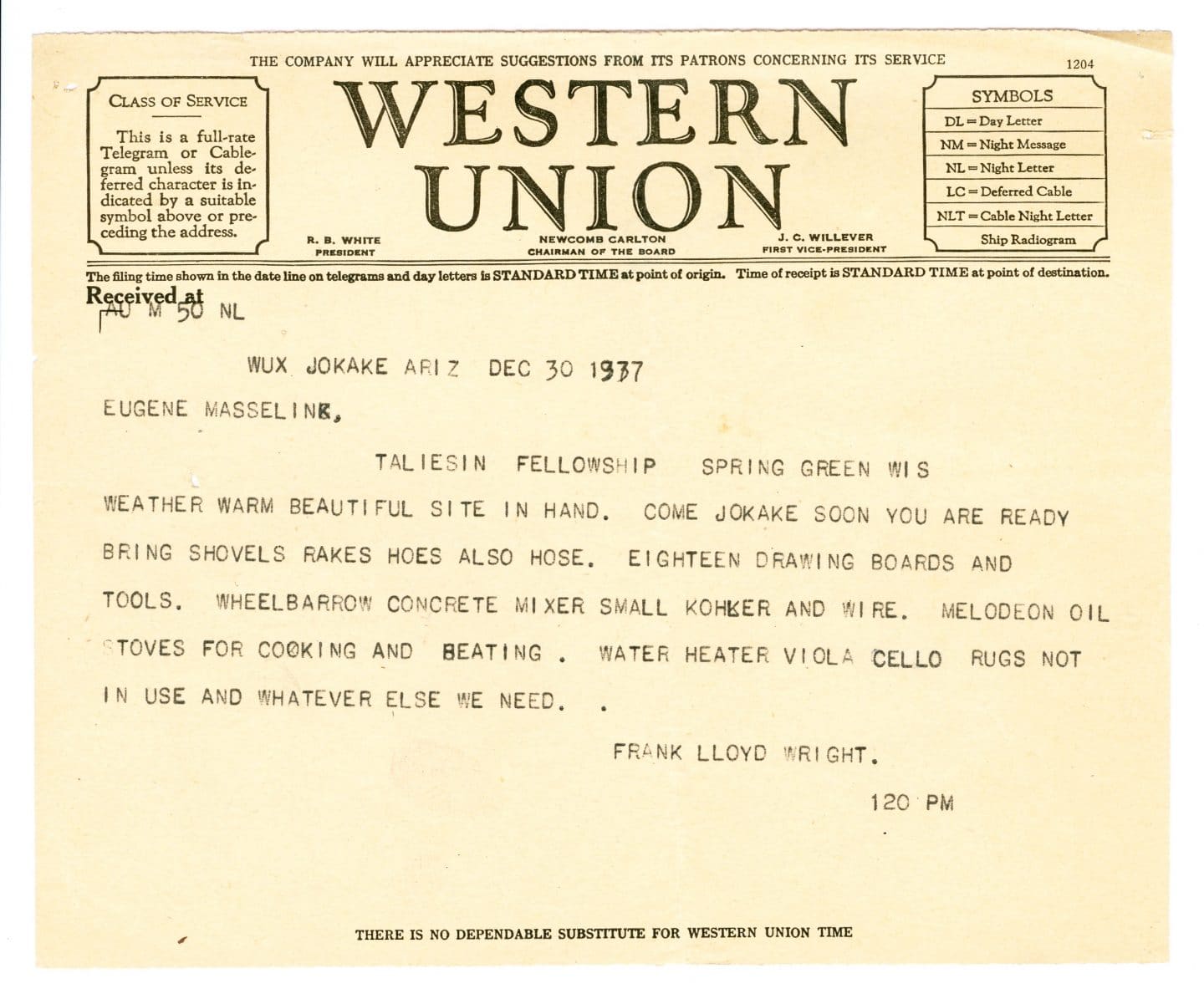

‘Beautiful Site in Hand’: Frank Lloyd Wright Telegrams Fellowship in 1937 from Arizona

Frank Lloyd Wright | Dec 30, 2017

On December 30, 1937, Frank Lloyd Wright sent a telegram to the Fellowship in Wisconsin, telling apprentices of the new site in Arizona that would later become Taliesin West.

The following excerpt titled “The Conquest of the Desert,” was taken from the fifth section of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “An Autobiography,” Form.

Taliesin West is a look over the rim of the world. As a name for our far-western desert camp we arrived at it after many more romantic names were set up and knocked down. The circumstances were so picturesque that the names ran wild—so we settled sensibly to the one we already had.

To live indoors with the Fellowship during a Northern winter would be hard on the Fellowship and hard on us. We are an outdoor outfit; besides it costs thirty-five hundred dollars to heat all our buildings at Taliesin, so it is cheaper to move Southwest. The trek across continent began November, 1933. Each trek was an event of the first magnitude. The Fellowship’s annual hegira with sleeping bags and camping-outfit, big canvas-covered truck, cars and trailers for thirty-five, was an event even in Fellowship life. To conquer the desert we had first to conquer the intervening two thousand miles in cold weather. The first several years we stayed at Dr. Chandler’s hacienda at Chandler, Arizona. Very happy there, too, but crazy to build for ourselves.

We were growing in proficiency.

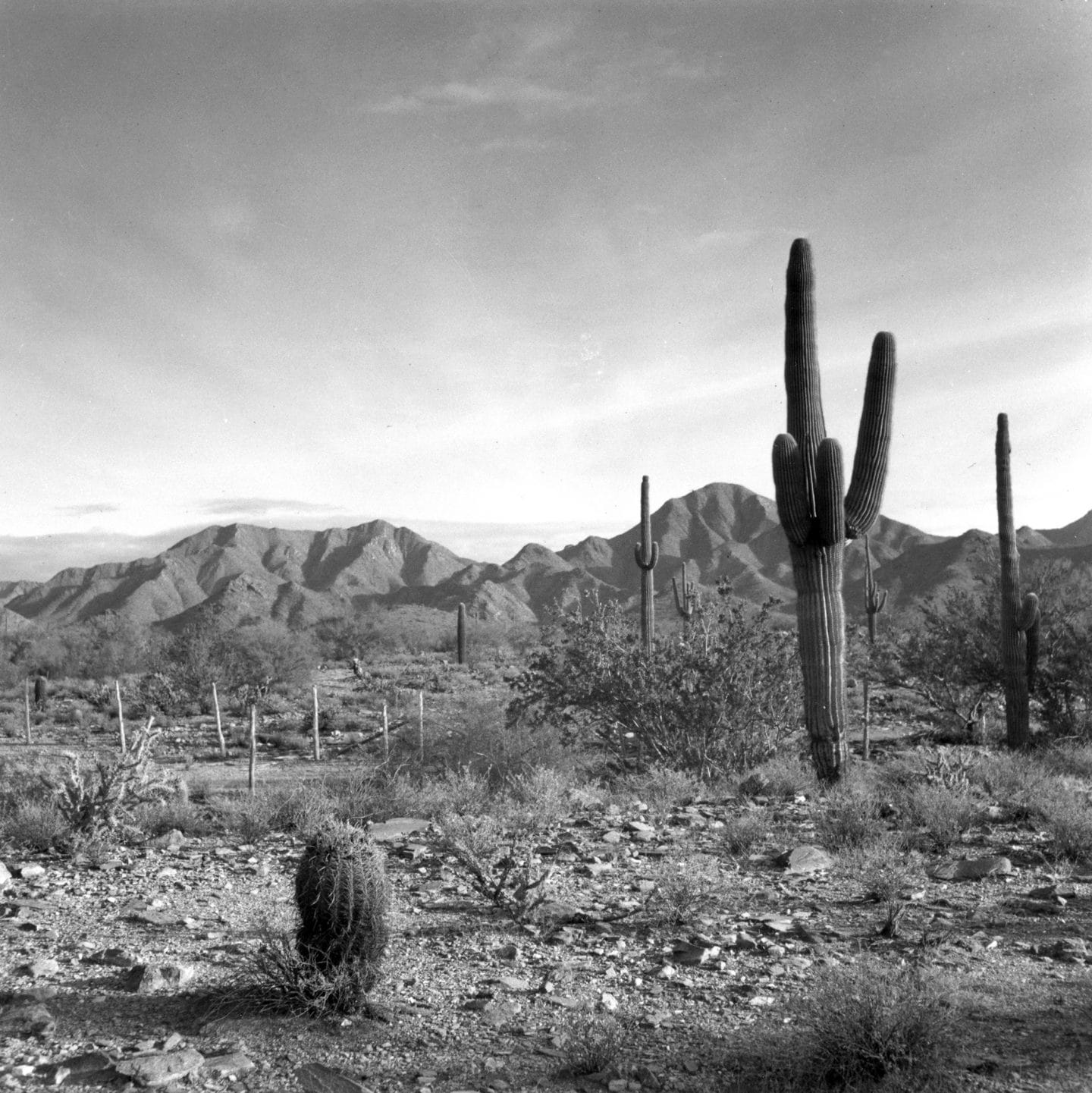

A major rule in the Fellowship has always been “do something while resting.” So we preferred to build something while on vacation. I was earning something again, now, as an architect, and we could get materials. But we first had to settle on a site. By this time that vast desert region, Silence and Beauty, was as familiar to us as our part of Wisconsin. There was plenty of room and plenty of superb sites, high or low—open or sequestered. Every Sunday, for a season, we swept here and there on picnics. With sleeping bags we went to and fro like the possessed from one famous place to another. Finally I learned of a site twenty-six miles from Phoenix across the desert of the vast Paradise Valley. On up to a great mesa in the mountains. On the mesa just below the McDowell Peak we stopped, turned, and looked around. The top of the world!

Magnificent—beyond words to describe! Splendid mystic desert vegetation, but what a bad road. The only trail crossing the great wash of Paradise Valley, the broad wash to the Verde River was this miserable G—d—- Hell of a road that that trail across the desert was in wet weather, so we found. And there was a rainy season until later it got to raining all the time.

But roads can be improved. The site could not be. The land could be bought from Stephen Pool at the Government Land Office. Pool said he was keeping it for some fellow (he said “fool”) who would fall in love with it and “do something with it.” We got about eight hundred acres together finally, part purchase, part lease. Next year we began to “do something with it.” We made the plans and we were all ready.

“On the mesa just below the McDowell Peak we stopped, turned, and looked around. The top of the world!”

We knew about what thirty apprentices, our little family alongside, needed—one of the things was “room.”

There was lots of room so we took it and didn’t have to ask anything or anybody to move over. The plans were inspired by the character and the beauty of that wonderful site. Just imagine what it would be like on top of the world looking over the universe at sunrise or at sunset with clear sky in between. Light and air bathing all the worlds of creation in all the color there ever was—all the shapes and outlines ever devised—neither let nor hindrance to imagination—nothing to imagine—all beyond the reach of the finite mind. Well, that was our place on the mesa and our buildings had to fit in. It was a new world to us and cleared the slate of the pastoral loveliness of our place in Southern Wisconsin. Instead came an esthetic, even ascetic, idealization of space, of breath and height and of strange firm forms, a sweep that was a spiritual cathartic for Time if indeed Time continued to exist.

The imagination of the mind of man is an awesome thing to contemplate. Sight comes and goes in it as from an original source, illuminating life with involuntary light as flashes of lightning light up the landscape.

The Desert seems vast but the seeming is nothing compared to the reality.

But for the designing of our buildings certain forms abounded. There were simple characteristic silhouettes to go by, tremendous drifts and heaps of sunburned desert rocks were nearby to be used. We got it all together with the landscape—where God is all and man is nought—as a more permanent extension of “Ocatilla,” the first canvas-topped desert camp out of Architecture by youthful enthusiasm for posterity to ponder.

Robert Carroll May

Superlatives are exhausting and usually a bore—but we lived, moved, and had our being in superlatives for years. And we were never bored.

From first to last, hundreds of cords of stone, carloads of cement, carloads of redwood, acres of stout white canvas doubled over wood frames four feet by eight feet. For overhead balconies, terraces, and extended decks we devised a light canvas-covered redwood framework resting upon massive stone masonry that belonged to the mountain slopes all around. On a fair day when the white tops and side flaps were flung open the desert air and the birds flew clear through. There was a belfry and there was a big bell. There were gardens. One great prow running out onto the Mesa overlooking the world, a triangular pool nesting in it—another garden sequestered for quiet with another plunge-pool with water raining down from the wall in one corner of it.

There were play-courts for the boys, spacious rooms for them, and there were pleasant guest-quarters on a wide upper deck overlooking the garden and the Mesa.

Said the local wise-man, “No water on that side of the valley—waste of money to try.”

But we tried and got wonderful water at 486 feet—85 degrees when it emerged at the pool. All went forward pretty much as usual, etc., etc., only on a less inhibited scale and upon the most marvelous site on earth.

Our Arizona camp is something one can’t describe and just doesn’t care to talk much about.—Something like God in that respect?

And how our boys worked! Talk about hardening up for a solider. Why, that bunch of lads could make any soldier look like a stick! They weren’t killing anything either, except a rattlesnake, a tarantula, or a scorpion now and then as the season grew warmer.

No, they weren’t killing anything: stripped to a pair of shorts they were just getting something born, that’s all, but as excited about the birth as the solider is in his V’s when they come through. More so if my observation counts.

The reward came.

Olgivanna said the whole opus looked like something we had been excavating, not building.

“The Desert seems vast but the seeming is nothing compared to the reality.”

That desert camp belonged to the desert as though it had stood there for centuries. And also built into Taliesin West is the best in the strong young lives of about thirty young men and women for their winter seasons of about seven years. Some local labor went in too, but not much. And the constant supervision of an architect—myself, Olgivanna inspiring and working with us as, working as hard as I—living a full life, too full, meanwhile.

The difficulty was for us, that the place had to be lived in while it was being built.

We were sometimes marooned for five days at a time. The desert devils would swirl sand all over us when it was dry. We could see whole thunderstorms hanging below us over the valley, see the winds rushing the clouds toward us, and we would get the camp ready as though we were at its mercy out on a ship at sea. At times on the way to and from Phoenix for supplies I would sit in the car, Olgivanna by my side, when my feet were on the brakes under water up to my knees.

The Masselinks coming to visit their son were lost in the desert water-waste overnight, and water was up to everybody’s knees until the afternoon of the next day. The son in an attempted rescue was almost carried away.

Frequently visitors trying to see us were nearly drowned in the desert.

Hardships toward the latter end of the great experiment were almost more than flesh and blood could bear. Olgivanna and I, living in the midst of a rushing building operation for seven years, began to wear down.

Otherwise our Fellowship life went on much the same, Taliesin or Taliesin West—except that the conspiracy of Time and Money was a little less against us.

Once you get the desert in your blood—look on the map of Arizona Highways for Taliesin West.