Architecture in Motion: The Gordon Strong Automobile Objective

Mark Reinberger | Nov 4, 2019

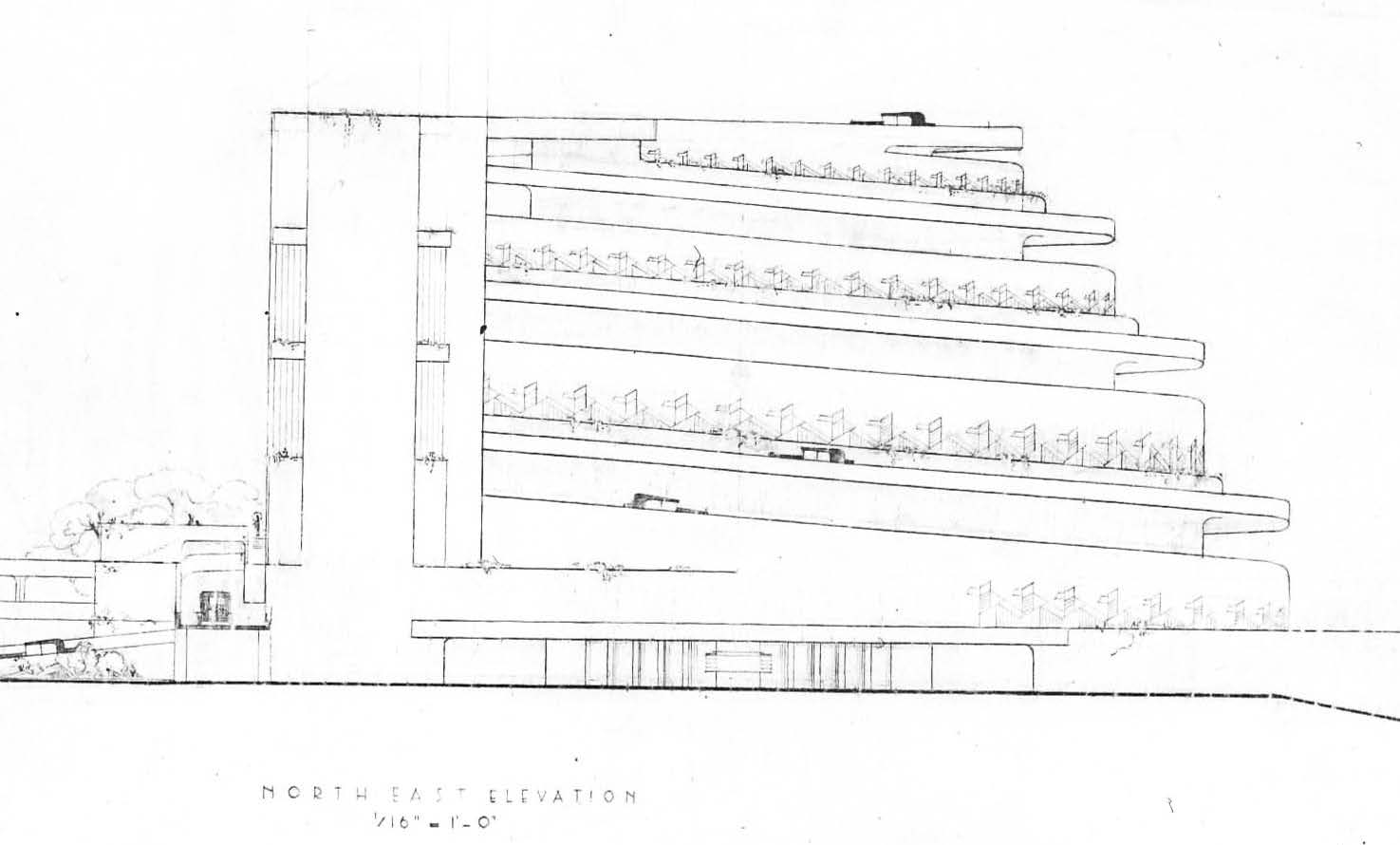

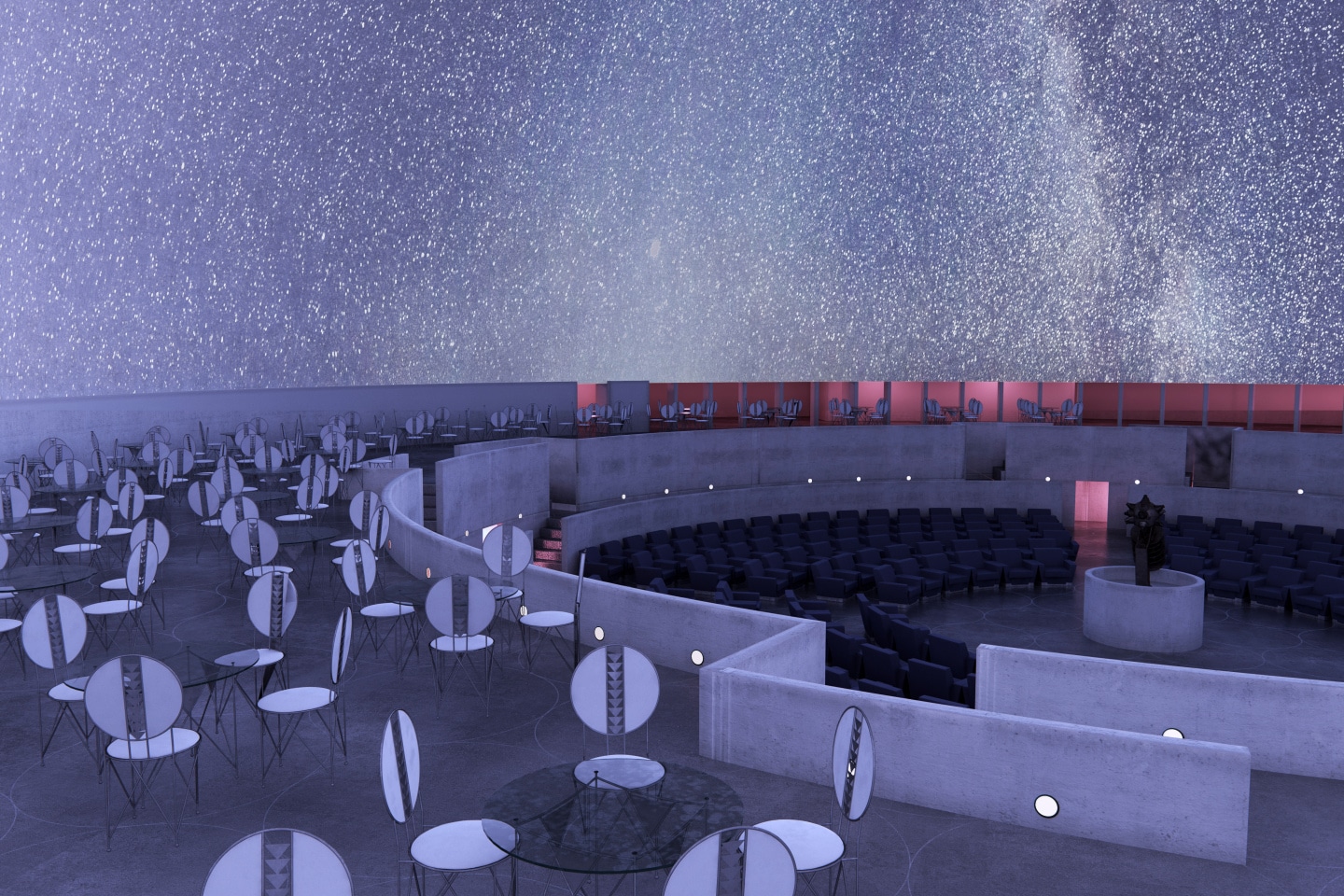

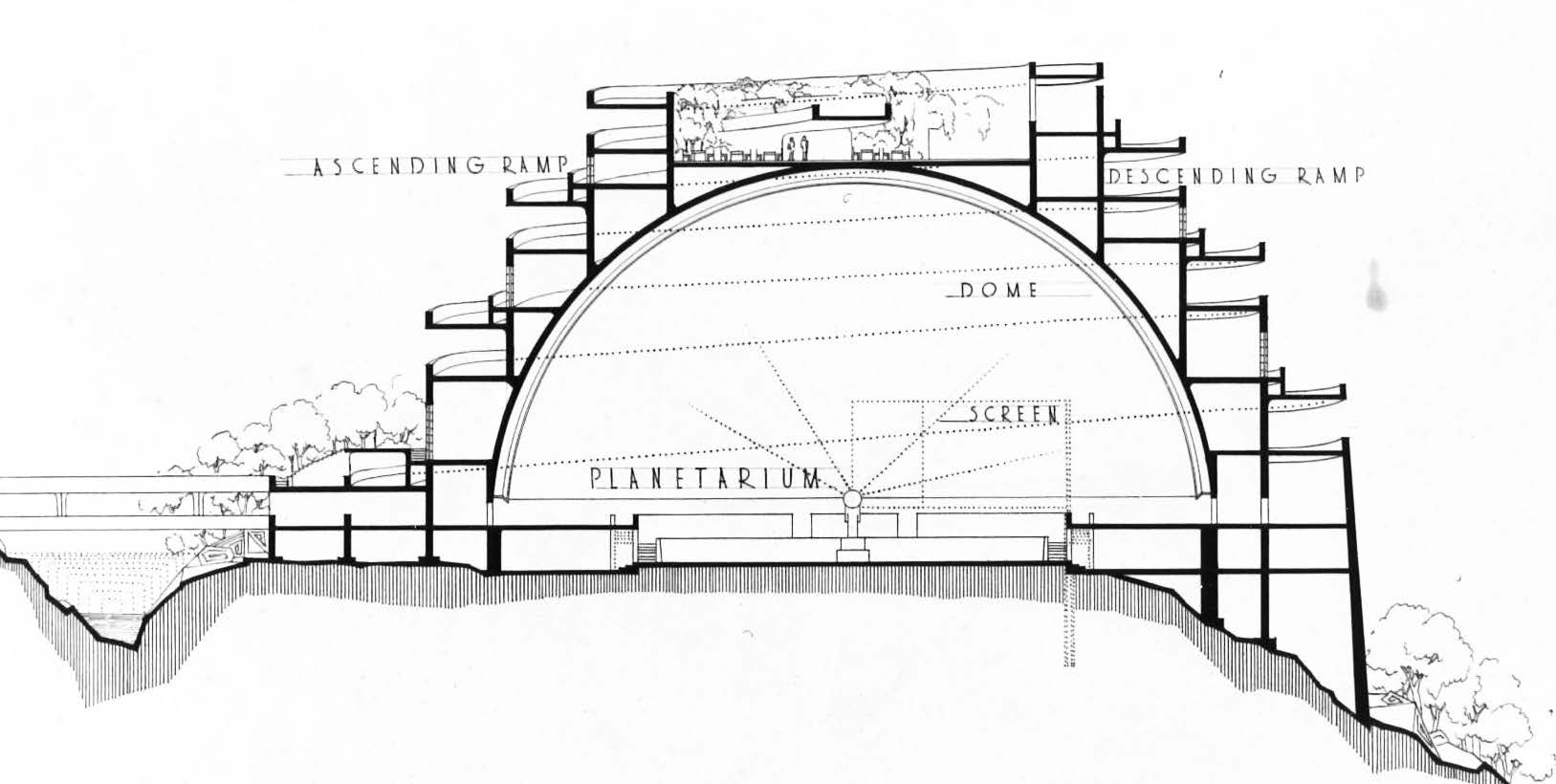

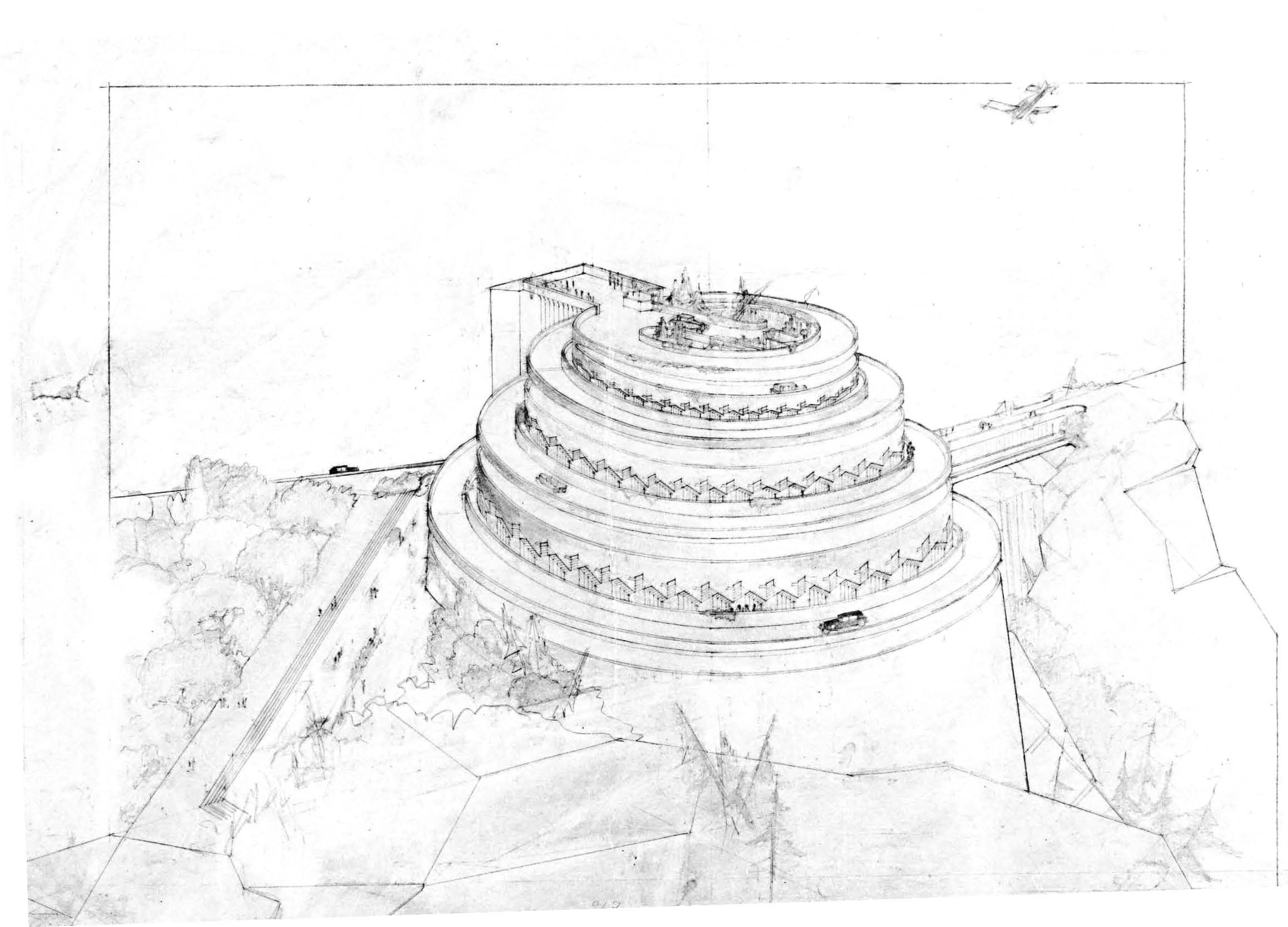

In the fall of 1924, Chicago businessman Gordon Strong commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design a resort facility for the summit of Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland, Strong’s rural estate near Washington, D.C. Referred to by client and architect as an “automobile objective,” the structure was to attract the large motoring public which had evolved in post-World War I America. Wright’s design was one of the most striking of his career. Inside it contained a huge domed planetarium; outside it resembled a circular ziggurat, with concrete automobile ramps spiraling up to the top and back down again.

All renderings by David Romero

Gordon Strong (1869-1954) was a wealthy businessman and real estate entrepreneur who had investments in Chicago and Washington D.C. While living in Washington in the 1890s he became familiar with Sugarloaf Mountain, a monadnock that stands in isolation above the surrounding rolling piedmont farmland. Strong bought the mountain with plans to develop a rural retreat. He built a road and overlook system which climbed to the summit, offering magnificent views. Requests to use the grounds convinced him that developing the mountain as a recreation area would be both a public service and a profitable enterprise. Sugarloaf’s proximity to Washington and Baltimore assured a solid market, and widespread automobile ownership in the 1920s allowed many urban and suburban dwellers to escape the city for the country. None of the many national and state parks which now fill the mountains of Maryland and Virginia yet existed.

Exterior rendering

Strong’s idea was for the summit of Sugarloaf to “serve as an objective for short motor trips on the part of residents of the vicinity.” He envisioned facilities for dinner and dancing, but most important to him were the open terraces and covered galleries that would offer a view from the mountain. Of the character of the architecture, Strong imposed three demands:

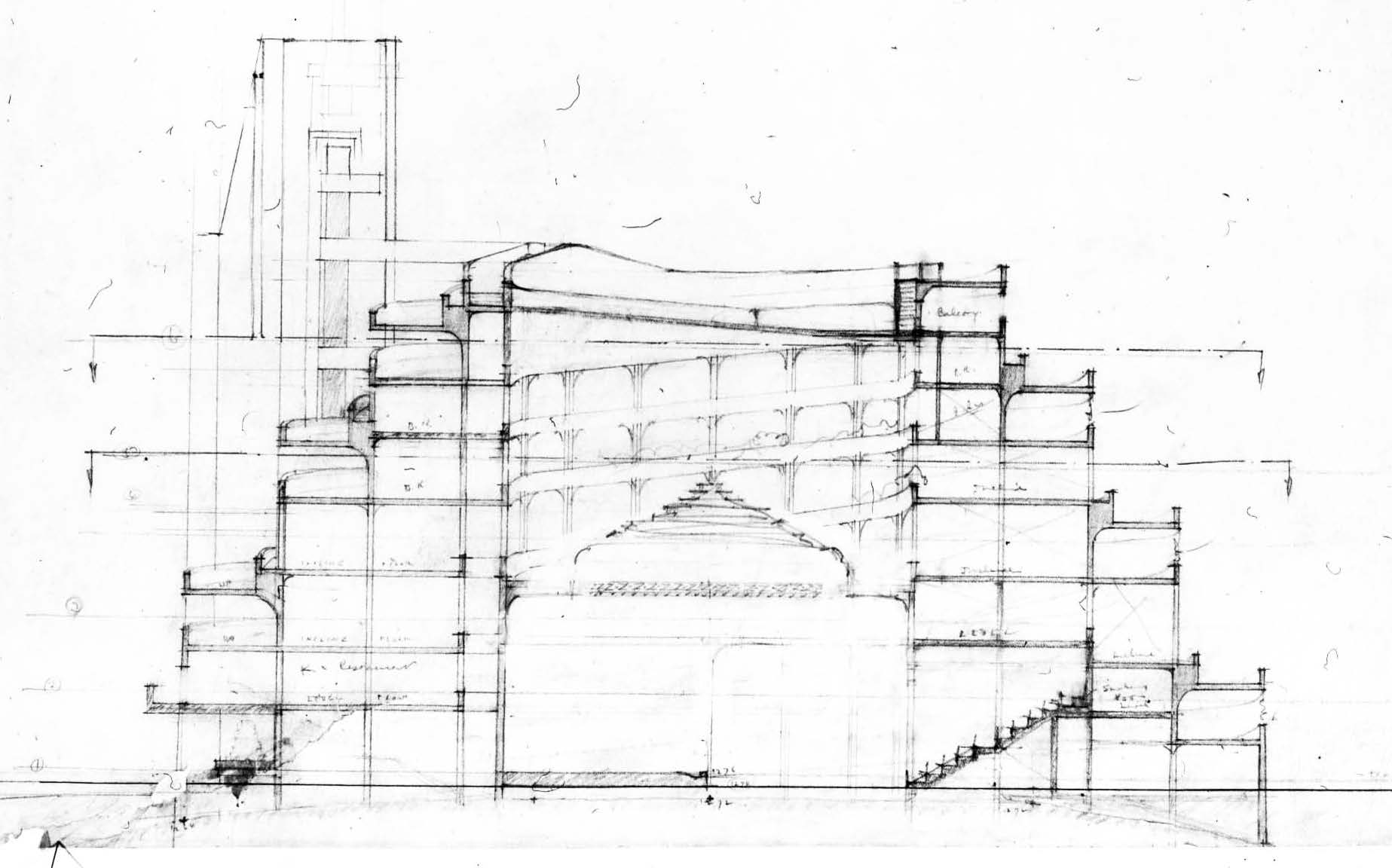

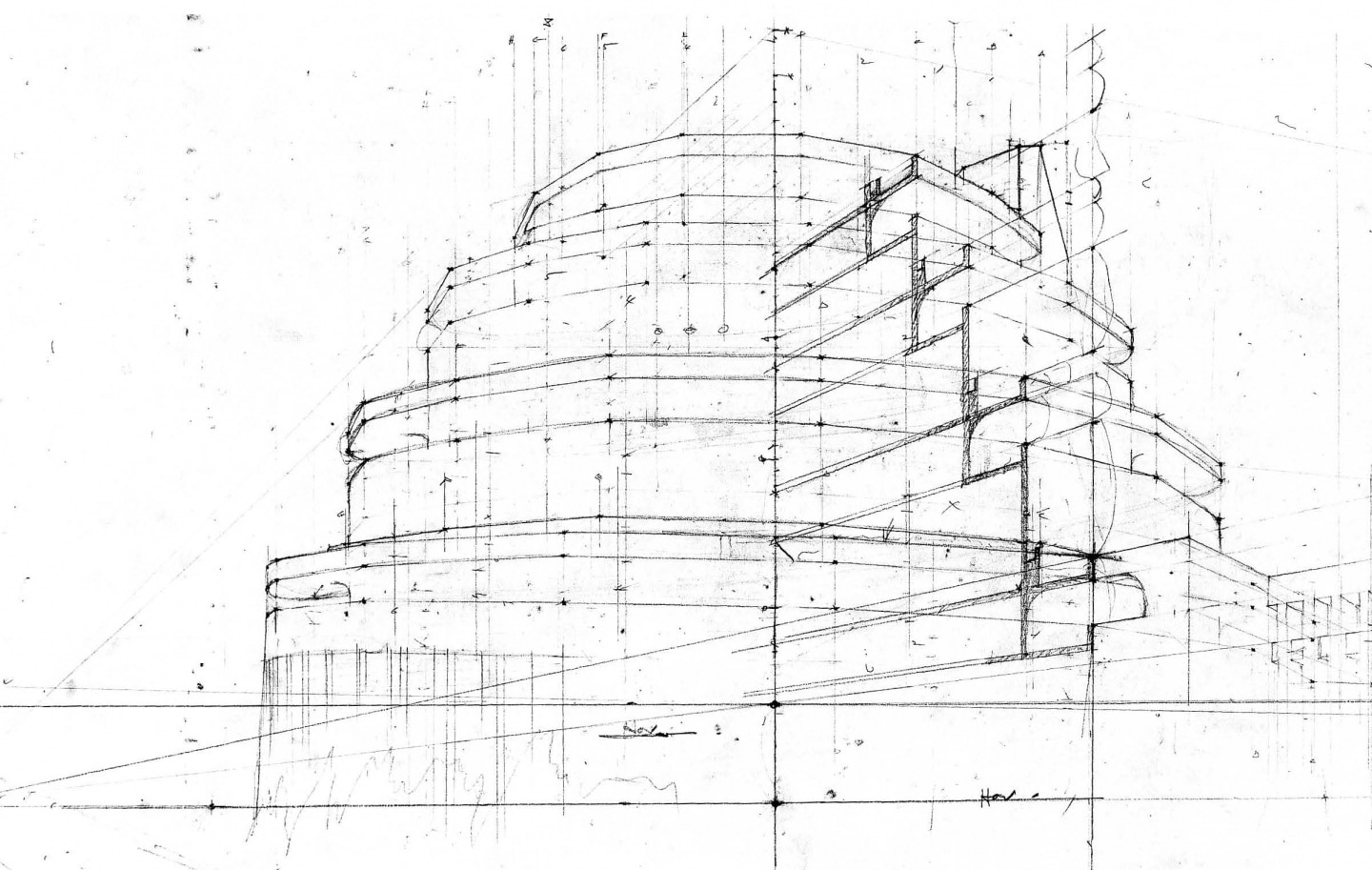

Archival elevation

a) To be striking, impressive, so that everyone hearing of the place will want to come at once.

b) To be beautiful, satisfying, so that those coming will want to come again, periodically, indefinitely.

c) To be enduring, so that the structure will constitute a permanent and credible monument, instead of proving a merely transitory novelty.

Interested in seeing more of Frank Lloyd Wright’s unbuilt works come to life? Subscribe to the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine today to receive our fall 2019 issue, Frank Lloyd Wright Unbuilt: The Nature of Water, which features photo-realistic renderings by Spanish architect David Romero of unbuilt Wright works on or near bodies of water.

Gordon Strong needed an architect for this project, and in 1924 he turned to Frank Lloyd Wright. The choice seems curious. Strong’s taste in art and architecture was conservative; he collected academic painting and conventional decorative art. Strong had expressed reservations, even disapproval, of Wright’s residential architecture around Chicago, although both men acknowledged the architectural possibility of modern technology. Letters suggest that Strong hired Wright for his propensity to dream. Strong saw Wright as an artist with a penchant for the fantastic and the novel. An automobile objective for the top of his mountain was both. And it was modern.

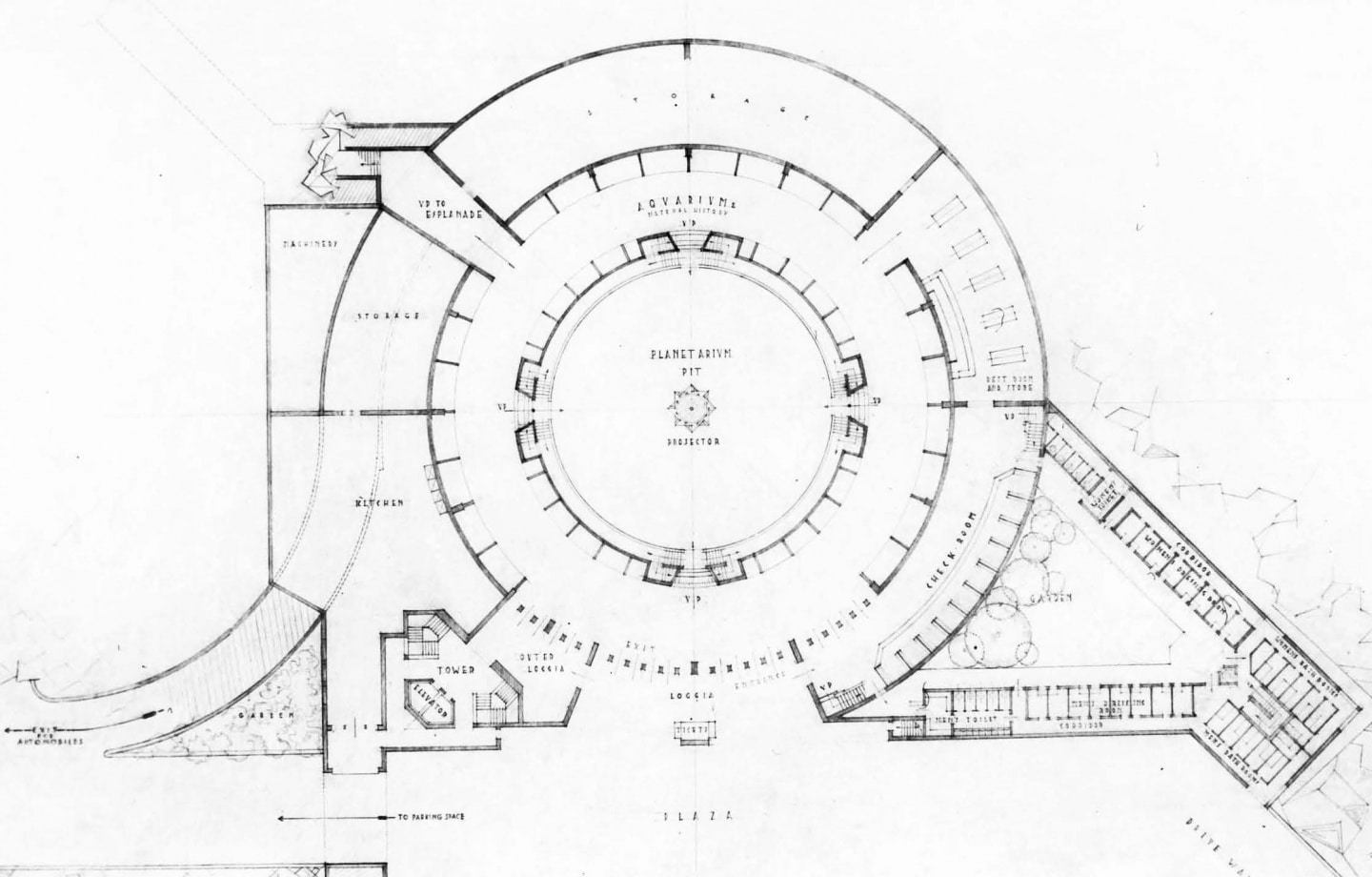

Strong gave Wright a program for the project. Some tourists would stay only briefly, some would picnic, some would want minimal food service, and others would want full dining facilities. Accommodation of the automobile, the common denominator of all visitors, was of prime importance. Strong’s first requirement was “to provide maximum facility for motor access to and into the structure itself.” In other words, the automobile was the raison d’etre of the project; it was not simply to be handled by parking lots some distance away. The objective was to hold one thousand people.

Archival plan

For picnickers and diners there were to be open air terraces, covered galleries for hot days, and enclosed rooms for cold or rainy weather. All visitors should enjoy the grandest views. There were provisions for kitchen and service facilities, two dance floors for entertainment, and thirty small bedrooms for overnight guests and employees. Strong also gave Wright the freedom to include “such additional elements as may occur to you as desirable.”

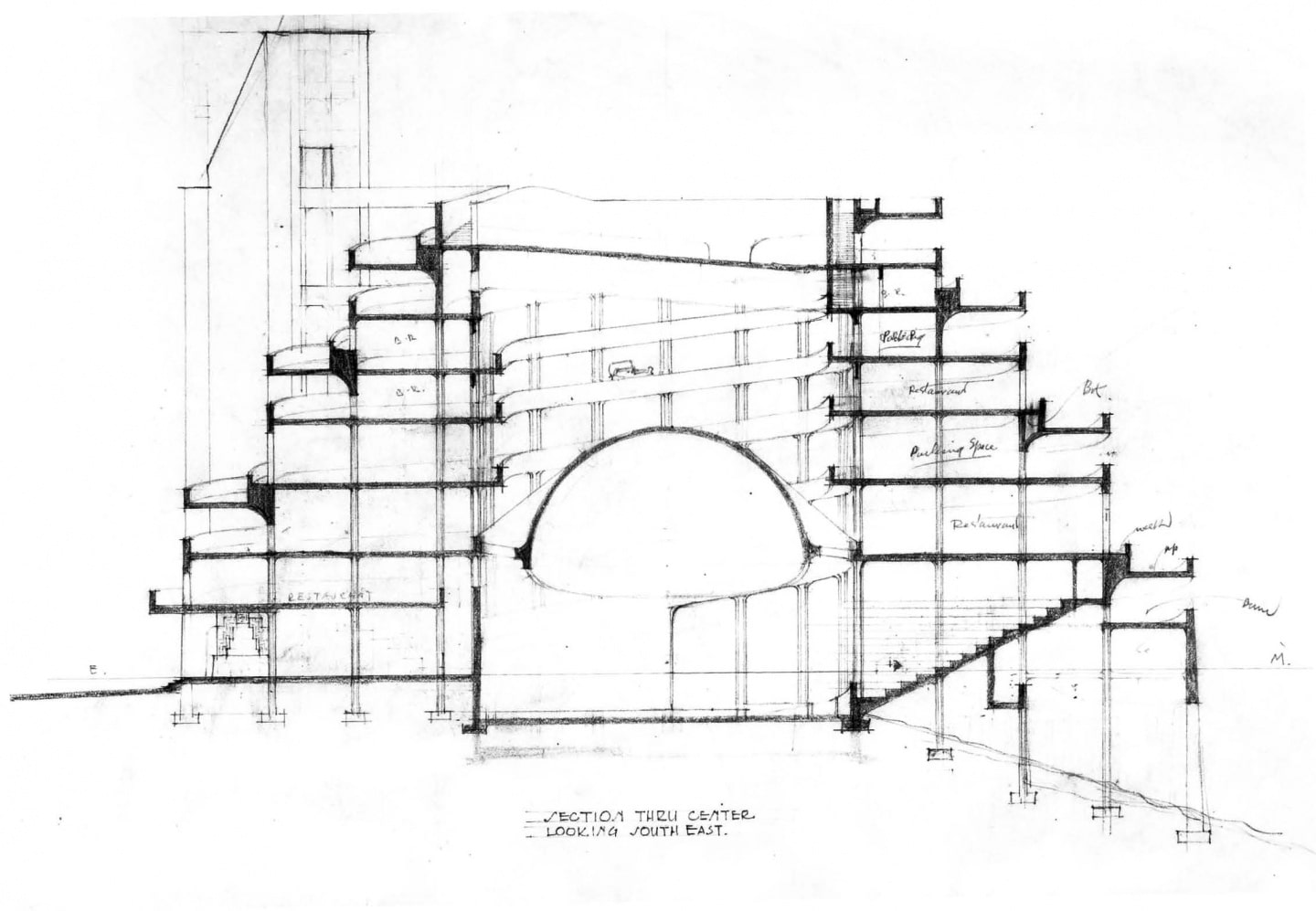

Wright began work on the design in the late fall of 1924. Decision on the basic circular ziggurat form was concluded by the end of the year; automobiles would ascend clockwise, be reversed by a ramp at the top, and descend by counterclockwise ramp underneath the ascending one. Initially Wright included a theatre inside the objective, along with dancing and picnicking facilities (as Strong had wished), but as design progressed a huge domed planetarium came to fill the entire inside. Other improvements in design made the objective more streamlined and more responsive to the moving automobiles that were its original inspiration. The planetarium itself made the project a kind of cosmic center, both metaphorically and literally. Like all domes, the planetarium suggested the vault of the sky, and it created an actual representation of the heavens. Aquaria and other natural history exhibits on the ground floor completed the miniature cosmos, with terrestrial nature below the astronomical realm.

Archival southeast section

Archival southeast section

Archival mezzanine plan

Archival lower level plan

Strong had specified that the building be on the summit, while Wright presumably selected the exact location. This gave Wright an opportunity to indulge his belief that there should be interaction or fusion between building and site. He thrust the building out over the mountain’s rugged cliff to increase the drama of both the structure and the views. The incorporation of greenery into his design helped Wright achieve his characteristic synthesis of nature and structure. The north terrace surrounded a sunken garden, while the south terrace was interlaced on several levels with planters and flower boxes. At the top of the spiral was a roof garden. From the balconies of the tower and even from the parapets of the automobile ramps, vines trailed down across the hard concrete surface. Set in the midst of nature, Wright clearly intended the Sugarloaf objective to become a part of nature.

Interior planetarium rendering

Archival section

Wright formally presented the proposal to Strong and a group of Chicago businessman in August 1925. The reactions of these other men are not recorded, but Strong himself expressed deep dissatisfaction with the plan. He declared Wright’s scheme to be unsuitable for his purpose or for his mountain. He wrote to Wright:

Your proposed “automobile observatory” impresses me as just that. As a structure of complete unity and independence, without any relation to its surroundings. It looks to me as it were designed to be used anywhere in the United States – on any sloping hill or mere raise of ground.

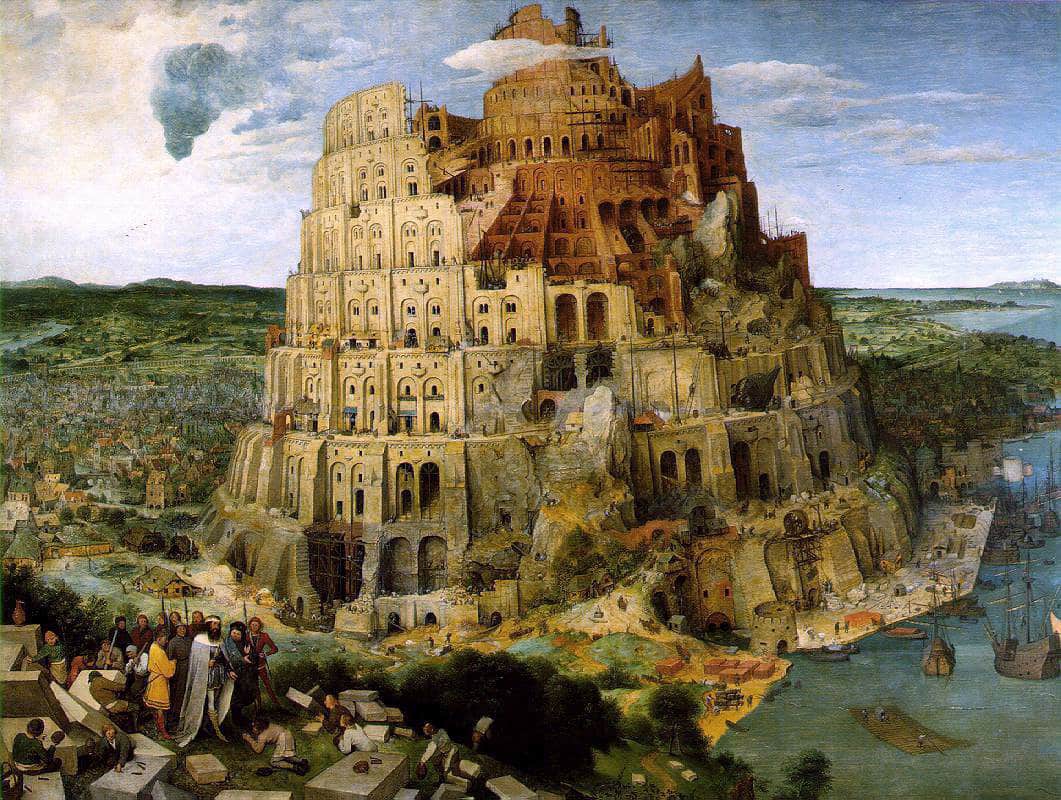

Strong continued his critique with the charge that Wright’s design was unoriginal, citing biblical architecture and comparing the Sugarloaf spiral to the Tower of Babel: “In devising that later type of structure, you have come straight back to the earliest.” Strong concluded his letter to Wright satirically, mocking Wright’s beliefs in the organic integrity of his design, and even enclosing a picture of the Tower of Babel:

Perhaps the particular view which I have of the Tower of Babel may not be in your collection…. You will note in the foreground a gentleman who, according to the Bible, lost his voice, and, according to the picture also lost his shirt: in endeavoring to explain that the structure under way possessed one thing anyhow – organic integrity. But the more he repeated the phrase, the less his hearers understood him. Finally, their understanding became so mixed that they did not understand each other. Which was the end of the first attempt at an externally ramped automobile observatory.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder: The Tower of Babel. Image via Wikimedia Foundation.

Wright was stung by Strong’s rejection, and his response to Strong showed that he could be equally acerbic:

Knowing your considerable capacities as I do I found … a new one – that of an actor, an actor in love with his own make-up – standing upon a stage built by himself. I hesitate to distribute the underpinning of that stage and spoil a clever if superficial conceit.

But why the ponderous precedents [the comparison of Sugarloaf design to Tower of babel] and omit … the fact that every carpenter that drives the screw proves me up. I have found it hard to look a snail in the face since I stole the idea of his house – from his back.

Exterior rendering

Wright continued, attacking Strong’s conservative taste, again defending the organic integrity of his design, and hinting at the rationale behind his concept:

I have given you a noble ‘archaic’ sculpted summit for your mountain. I should have diddled it away with platforms and seats and spittoons for introspective or expectorating business men and the flappers that beset them, and infest the whole with ‘eye’-talian squirt guns and elegant balustrades … leaving the automobiles in which they both now really live and have their beings, still parked aside, –betrayed and abandoned as usual.

Wright’s response to Strong’s rejection indicates that his primary concern in this project was the accommodation of the automobile. This was the main generator of his spiral plan. In an early letter to Strong, Wright amplified this: “An automobile ‘objective’ I take it, should make a novel entertainment out of the machine in normal use.” He decided the spiral’s suitability for the purpose, allowing for the “movement of people sitting comfortable in their own cars … with the whole landscape revolving about them, as exposed to view as thought they were in an aeroplane.” Of the double ramp system he added, “The spiral is so natural and organic a form for whatever would ascend that I did not see why it should not be played upon and made equally available for descent at one and the same time.”

Although a bitter defeat, the Sugarloaf Mountain project proved to be a catalyst for Wright, one which provided him with the opportunity to explore new themes and experiments with new forms. His design for Sugarloaf Mountain was a demonstration of his belief that the automobile changed perception of space, and his ultimate celebration of the automobile’s power to generate new patterns of leisure and living. In using the spiral, he had created an architecture for the automobile in motion, and within the project’s evolution he explored a variety of new architectural ideas. Wright had always been captivated by the experience of whirling around a hill, through space and nature. He wrote about running so around Taliesin’s hill; he sent his house there whirling around the hill, and in Sugarloaf he raised the scale and speed to that of automobiles whirling around a mountain.

Archival rendering

Wright remained captivated by the spiral and continued to develop its potential in several later projects. He utilized a spiraling ramped ziggurat in the Self-Service Garage and the Point Park project, both for Pittsburgh (both 1947). Both involved the automobile and the park project also included a theatre, planetarium, and aquaria; it was actually an enlarged version of Sugarloaf. A similar structure had appeared as Broadacre City’s community center.

Archival section

In 1957 Wright again enlarged the scheme, to truly urban scale, in the Opera House and Gardens for Baghdad, Iraq, a complex which he called the “Garden of Eden,” with a quite literal evocation of Sugarloaf’s cosmological significance. And of course the most famous descendant of the Sugarloaf automobile objective is the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, where Wright turned the spiral upside down, gave it to pedestrians, and placed it in setting very different from the forests of Sugarloaf Mountain. ∎

This article originally appeared in the fall 2018 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine, “Unbuilt Frank Lloyd Wright: Architecture for the Automobile”

Mark Reinberger, Ph.D., is a Professor in the College of Environment and Design at the University of Georgia, where he teaches courses in architectural history and preservation. He holds degrees from the University of Virginia and Cornell University in the history of architecture, art, and urban planning. Besides many articles, he has published Utility and Beauty: Robert Wellford and Composition Ornament in America (University of Delaware press, 2003) and, with Elizabeth McLean The Philadelphia Country House: Architecture and Landscape in Colonial America” (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015).

David Romero is an architect, computer graphic artist, and passionate about history. As a student, he discovered the legacy of Frank Lloyd Wright and fell in love with his work. He has continued to enjoy Wright’s teachings and work since then. He currently resides in Madrid, Spain, where he works in the fields of architecture and architectural visualization. His project “Hooked On The Past,” dedicated to recreating relevant architectures of the past using 3D modeling techniques, has had a great media impact.