A Friendship in Photographs: Pedro E. Guerrero & Frank Lloyd Wright

Emily Bills | Sep 14, 2018

Architectural and urban history scholar Emily Bills writes about how a young, talented photographer went on to capture some of the most iconic photos of Frank Lloyd Wright and his work, while forming a close bond with the architect.

Header image by Kaneji Domoto

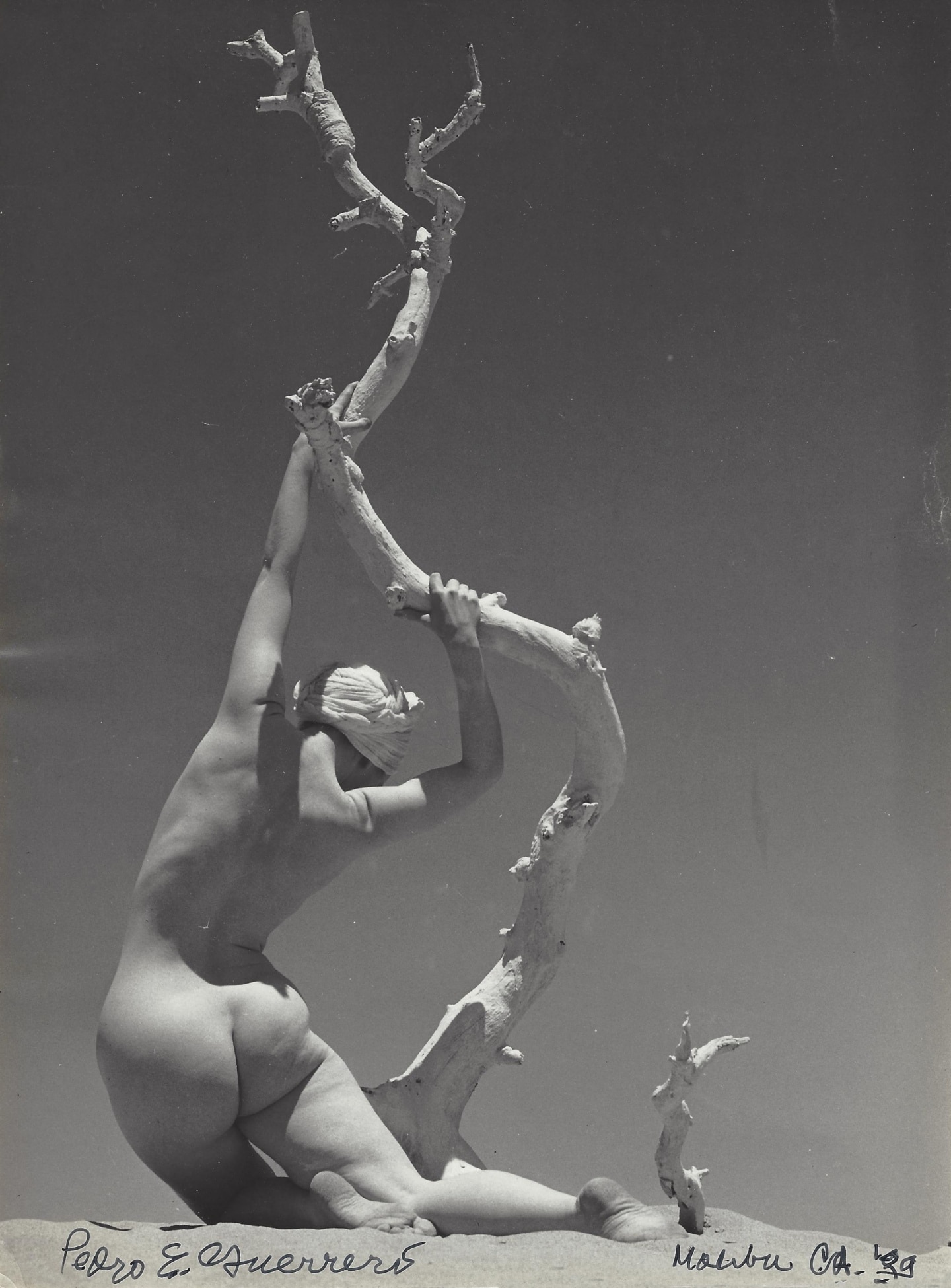

In 1939, at age 22, Pedro E. Guerrero made the short trip from his home in Mesa, Arizona to a new architecture school housed in a low‑slung complex of buildings outside of Scottsdale. Guerrero had recently left art school and was searching for a way to practice photography. When his father suggested asking the head architect for a job, Guerrero made an appointment to show his portfolio. The architect happened to be Frank Lloyd Wright, the buildings were Taliesin West. Guerrero knew little about Wright, but the architecture—what he perceptively described as a “sculpture of stone and redwood rising out of the desert”—captivated him. Wright reviewed his student photos, commenting on a series of black and white nudes at the beach. “I see you have a fondness for the ladies,” he noted.

And thus began a 20-year friendship, one girded by mutual respect and Guerrero’s unique ability to joke with the great master. Over time they developed a strong father-son bond. This connection, coupled with Guerrero’s aptitude for recognizing the human element in oversized personalities, is revealed in portraits of the architect that extend from that first year until two weeks before Wright’s death. Guerrero thus did more than produce enduring photographs that solidify Wright’s built legacy, he also sought to understand the architect’s interior motivations and provide revealing and empathetic interpretations of the person behind the work.

Student photography class in Malibu, California, 1938. Part of a series of nudes Guerrero shared with Wright during his first interview. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

The relationship between architect and photographer represents the coming together of two creative visions. This can be a fruitful exchange, and the savviest architects cultivate a partnership with a single photographer so there is consistency between the imagery over time. Wright was keenly aware that, far more than the phenomenological experience of walking through a building, it was visual representation reproduced and distributed that defined how most people would engage his creations. Guerrero’s technical skill and sensitivity to site and environment did much to make Wright’s projects recognizable, but he never rested on the repetition of a singular compositional approach. Instead, he allowed unique building elements or local conditions to shape his photographic interpretations.

The result is a diverse collection of photographs that has been included in nearly every exhibition and publication about Wright and his work, including the current celebration of Wright’s 150th birthday at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. 2017 also marks Guerrero’s 100th birthday, and it is fitting that these two anniversaries should coincide. Although Guerrero’s professional career ranged from experiments in street photography to architectural photographs for the major lifestyle magazines of the midcentury period, such as House & Garden, Vogue, and Harper’s Bazaar, he achieved most renown as Frank Lloyd Wright’s photographer of choice.

Born in 1917 in Arizona, Guerrero experienced the challenges facing Latinos in the Southwest. Although his parents, both Arizona‑born, spoke English, he was forced to attend a grammar school designated solely for Latino children. He saw little opportunity to advance professionally after high school and, in 1937, decided to join his brother at Art Center College in California. As stated in his biography “the life of an artist seemed exotic and without the bigotry and rejections I felt in Mesa.” When told the painting courses were filled, he enrolled in photography and felt an immediate kinship to the art form.

Guerrero (top right) with Taliesin Fellows in Wisconsin, 1940. Photo by Edgar Tafel.

Robert Llewelyn Wright House in Bethesda, Maryland. Designed 1953, photographed after the architect’s death for Architectural Forum. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

Wright and Olgivanna cultivated an atmosphere of pageantry in which the apprentices engaged multiple areas of the arts. The couple enjoyed being entertained, as can be seen here in a 1940 costume party staged just before their return to Arizona. Guerrero, who was himself dressed as a sultan in turban and billowing pants, captured Wright and Olgivanna dressed to resemble Montenegrin royalty. Wright’s boots with one‑and‑a‑half inch Cuban heels are visible in the foreground. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

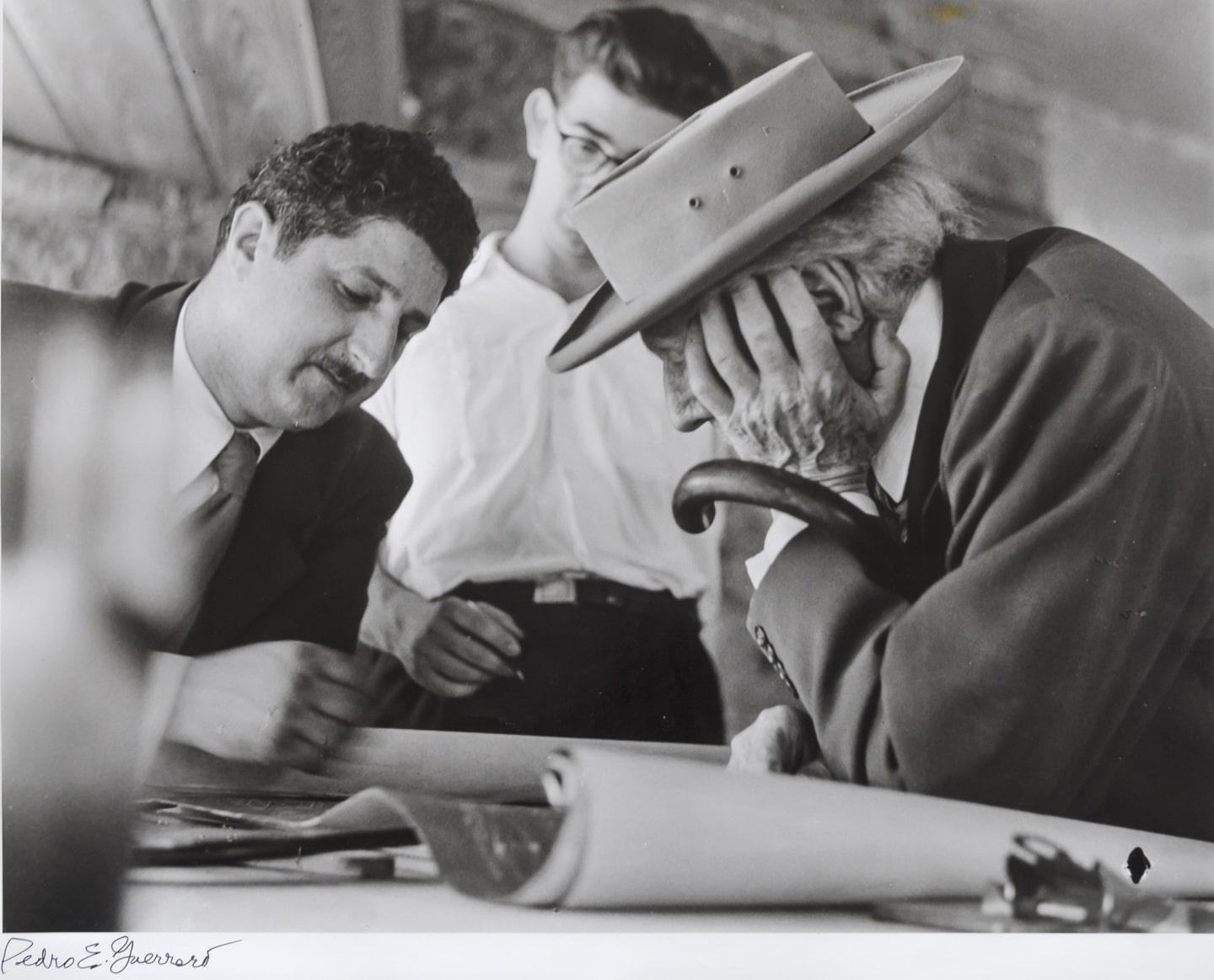

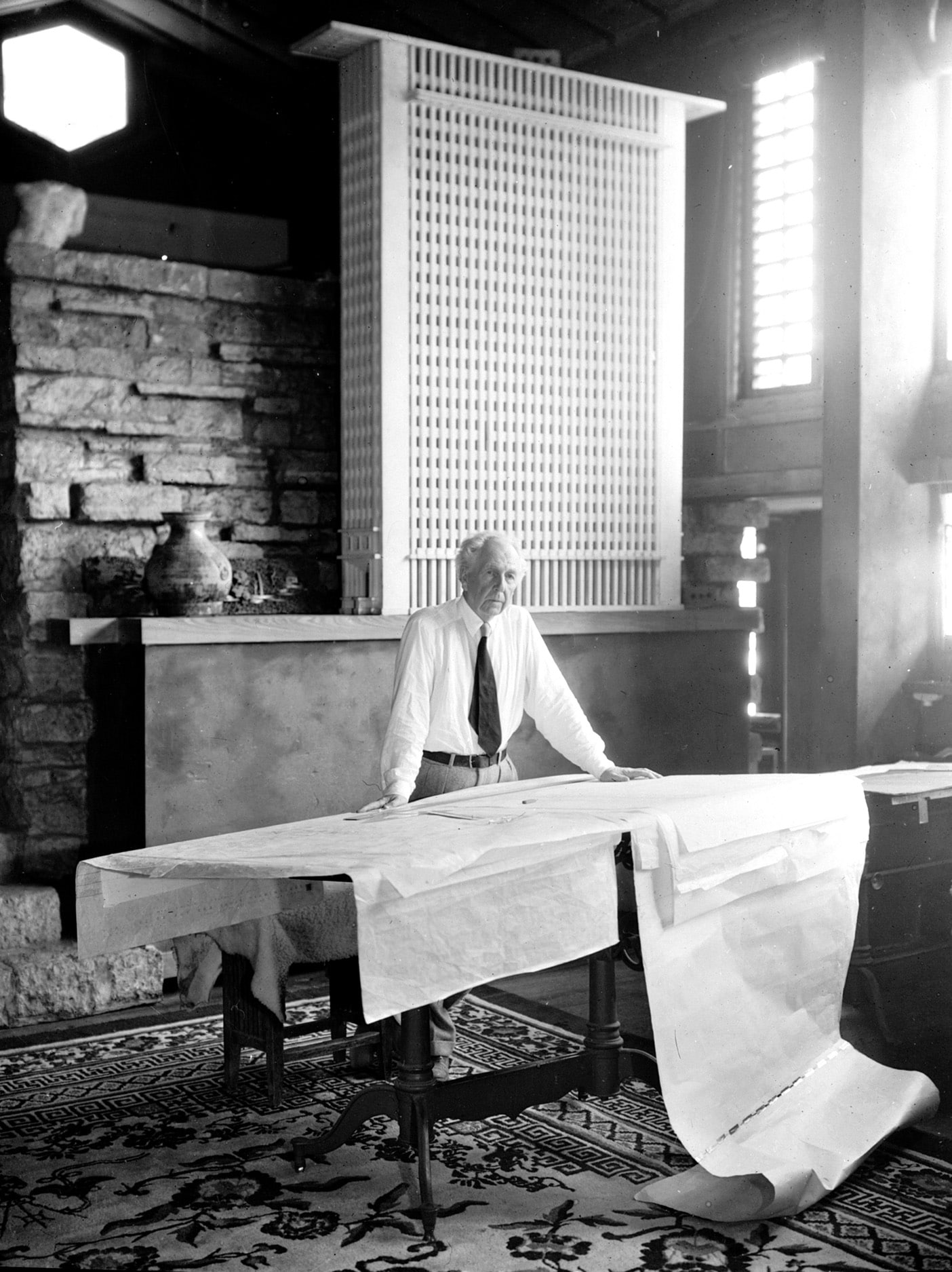

But Guerrero found opportunities for informal moments … a simple but astute portrait that tells much about Wright’s love for the work itself, the routine deliberation over design details and revisions.

Wright and his builder David Henken revising plans, 1952. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

Later at Taliesin, Guerrero also found shelter from prejudice and opportunities for creative expression. From the very beginning, Wright expressed a generosity of spirit toward the young photographer. He gave him free reign to explore the property, allowing him space to photograph whatever moved him. Wright’s only request was that he wanted to recognize the buildings as his own, which mandated a particular perspective. The two men were about three inches apart in height, and Wright told Guerrero he shouldn’t think of himself as short, but liken taller people to overgrown weeds. He asked Guerrero to capture the work from their shared vantage point, the perspective from which he designed at his desk.

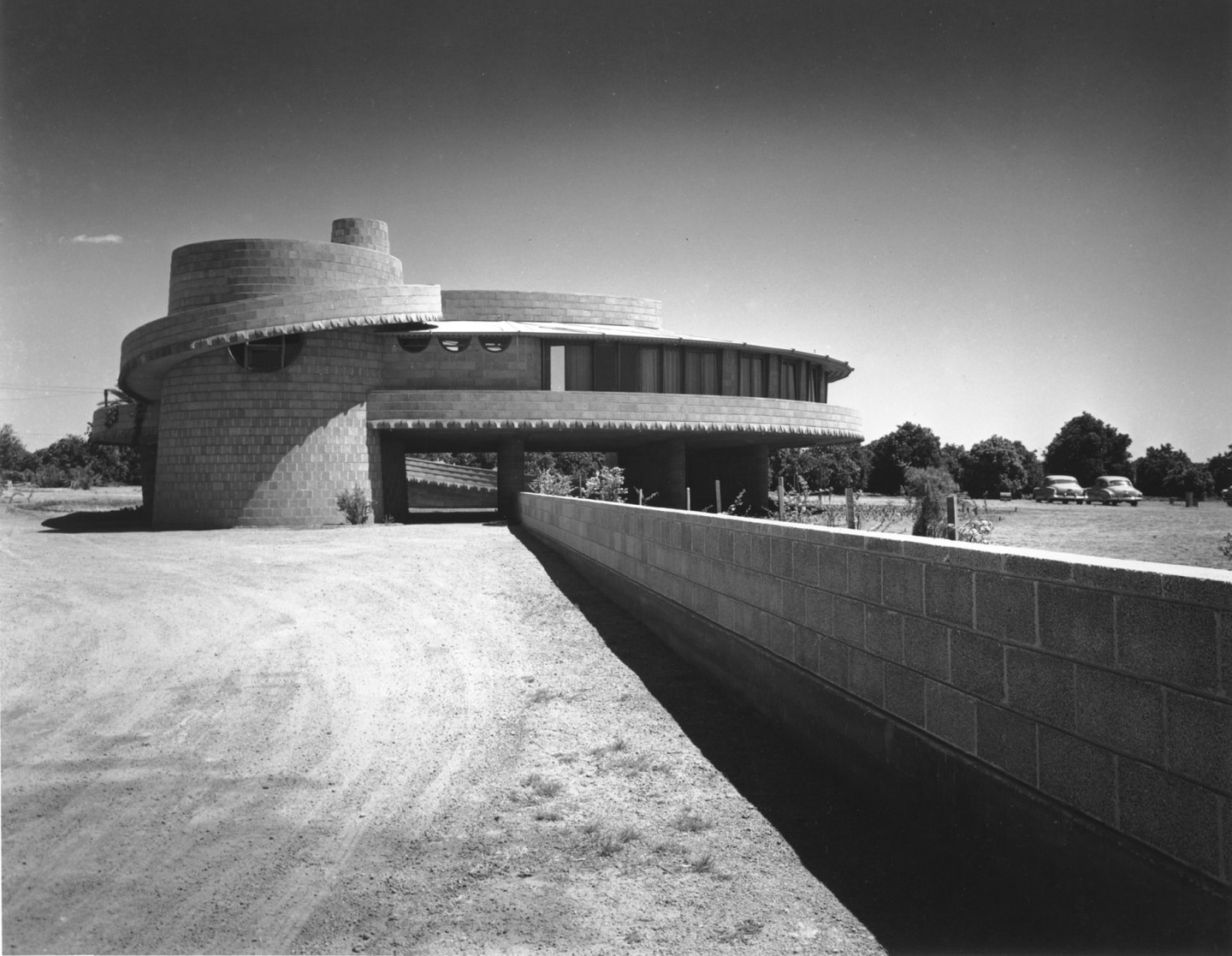

Perhaps more significant to Wright than perspective, however, was Guerrero’s remarkable technical ability to express the desert’s extreme conditions, with which Wright had been intently preoccupied. While the architect was new to Arizona, Guerrero had an intuitive understanding of the harsh light and didn’t shy away from it. As seen in his photographs of the David & Gladys Wright House, he often foregrounds the cruel sun, the severe shadows, and the way these conditions can reduce structure to mere abstraction. In a highly composed shot of Taliesin West, an elongated roofline and diagonal strut are rendered as a tight geometric frame, a dark barrier boxing the viewer into a space of shelter. A building section juts out in mid‑ground, just before the image releases us into an expanse of light and desert brush. It’s a masterful exercise in depth of field.

In this photo of the David & Gladys Wright House in Phoenix, Arizona, Guerrero tackled the harsh desert light and deep shadows in the sparse landscape. The expertly composed image, in which viewer and house are connected through the deep recess of the concrete block wall (what Wright identified as the house’s “anchor”), captures the heat’s intensity. In his biography, Guerrero recalled that Wright and his son David had an argument over bougainvillea vines that David had trained to soften the architecture. When Wright commanded they be ripped out for the photograph (published in House & Home in 1953), David kicked the architect and photographer off the property. Guerrero was tenacious and stayed behind for a photograph from the end of the driveway. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

Wright conceptualized the Fellowship as a holistic education in architecture and he likely envisioned Guerrero’s photographic work in this context. In Arizona, Guerrero chose to live at home but he joined the Fellowship when he learned they were returning to Taliesin in Wisconsin for the summer. His photographs of the architect in the Midwest— reclining in a field of wild Wisconsin grasses, participating in a costume party put on by the Fellows, being driven around in his beloved Crosley convertible—are important documents of Wright outside of the highly managed image he constructed for himself. In a photograph of Fellows picnicking, Wright is captured in a candid state of repose, at ease in the daily routine. It’s an unscripted moment, the Fellows more engaged with their own conversations than with Wright. Yet the imagery also suggests Guerrero was complicit in supporting the mythology Wright wove around his career. The architect is positioned at center, surrounded by students like they’re his disciples. The pictorial merging of man and meadow also stands as an animate incarnation of Wright’s ethos that there should be no boundaries between an architect’s engagement with nature and professional practice.

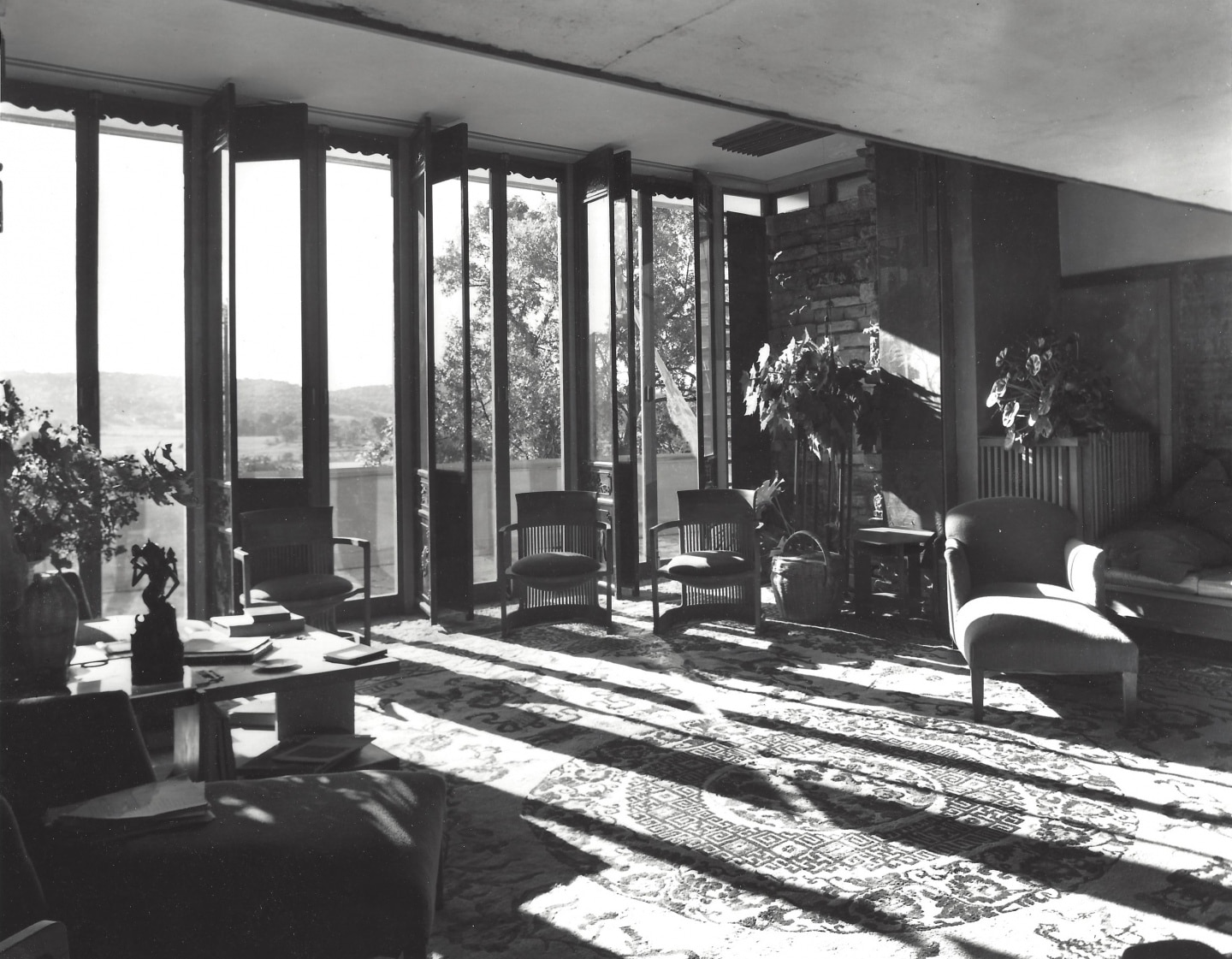

Sitting room with balcony, Taliesin, Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1952. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

Guerrero captures Wright and Olgivanna (at the wheel) in a Crosley convertible at Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1953. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

He gave him free reign to explore the property, allowing him space to photograph whatever moved him. Wright’s only request was that he wanted to recognize the buildings as his own, which mandated a particular perspective.

Wright and the Taliesin Fellows enjoying their daily luncheon picnic. Taliesin, Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1940. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

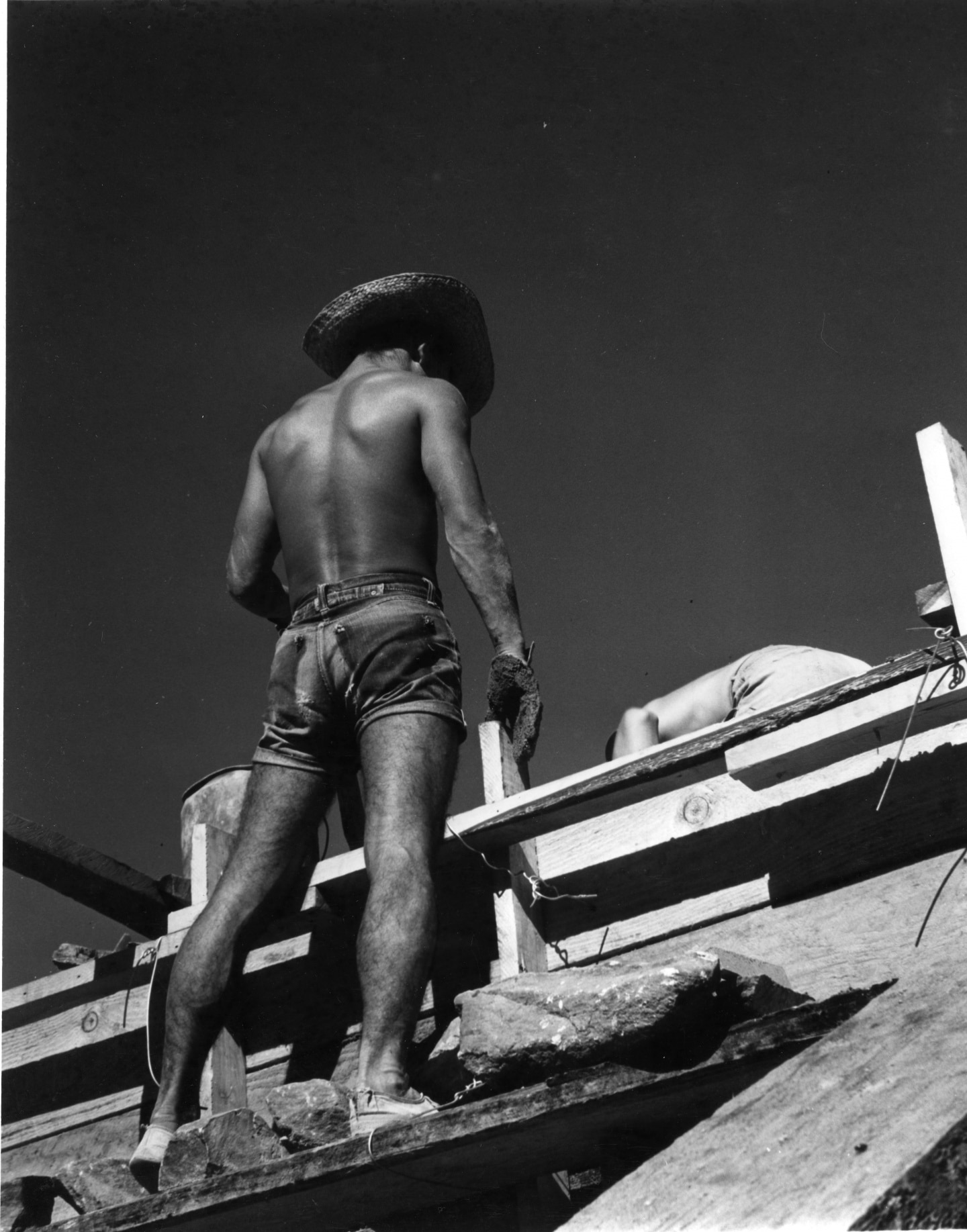

Guerrero photographed Taliesin West as it was being built and thus documented the structures as they evolved. A significant aspect of that process was the labor involved, which Guerrero captured in photographs of the apprentices at work. Guerrero focuses on the physicality of construction, highlighting male muscularity through rich chiaroscuro and a near melding of body and building. The interpretation finds parallels with Socialist Realism of the 1930s, with which Guerrero was surely familiar. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

As he did with Wright’s buildings, Guerrero also adjusted his portraits to reflect Wright’s requests and moods. A traditional composition renders the architect in the manner of a great master, posed in a commanding stance behind his desk, eyes locked on the camera. But Guerrero found opportunities for informal moments. Compare that photograph with an image of Wright chin in hand, deep in conversation over a drawing. It’s a simple but astute portrait that tells much about Wright’s love for the work itself, the routine deliberation over design details and revisions.

This push and pull between reverence and informality continued to characterize not only Guerrero’s photographs, but also their friendship. While they often shared a witty repartee, Guerrero always addressed the architect as “Mr. Wright.” As a member of the Fellowship, he spent his time relegated to the darkroom to satisfy Wright’s intense production schedule. Yet Guerrero was also able to establish an independent career that Wright supported. From their first meeting, Guerrero insisted on using his own 4×5 camera, which enabled maximum flexibility and control over light and composition, as opposed to Wright’s less flexible 5×7 without a shutter, which the architect initially suggested he use. When Guerrero enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1941, Wright, who was a committed pacifist, was candid about his disapproval. Still, Wright unfurled a roll of bills, handed Guerrero one hundred dollars, and promised him work when he returned. He held true to that promise.

After the war, Guerrero moved to New York to launch an architectural photography career, which he did with the help of his portfolio of Wright buildings. In return, Guerrero made the loyal decision to only accept freelance jobs from magazines during Wright’s life so that he was available when the architect required his services. In this way, Guerrero became an important connection between Wright and the New York‑based publishing industry.

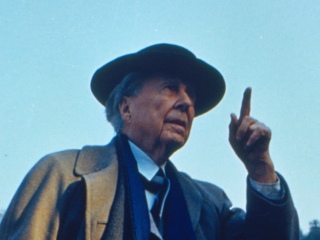

Portrait of Wright, Taliesin, Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1947. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

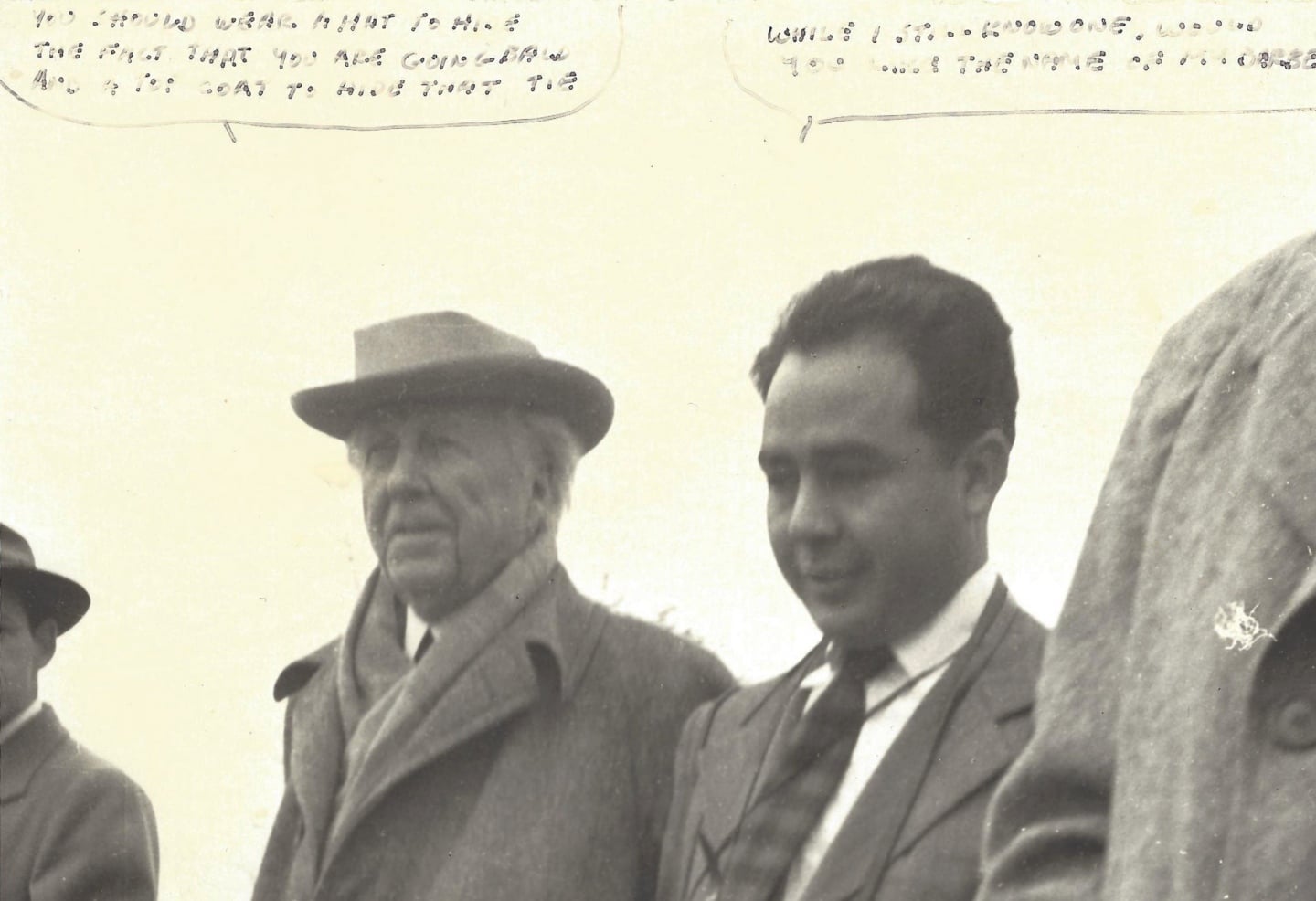

Guerrero worked with Wright during a renewed, active period late in the architect’s career. When they met, Wright was 72 and building more than ever. Guerrero was regularly called to photograph completed structures, such as the Oboler House in California and an expanding portfolio of Usonian houses, including a colony in Upstate New York. It was during one of those visits to the Usonian colony that someone captured Guerrero and Wright standing together in a moment of relaxed exchange. In many ways their relationship is best understood through the stories Guerrero recounted at public talks, in his own biography Pedro E. Guerrero: A Photographer’s Journey, and most recently for the documentary of the same name, which aired on PBS as part of its American Masters series. Wright was a great joke teller, matched only by Guerrero’s own masterful sense of a well‑timed punch line. In the opening photo they are pictured, Wright in his porkpie hat, Guerrero in a checkered tie, camera around his neck. In the Guerrero archive, there is a version of the photograph with the photographer’s good‑humored, imagined inscription scrawled across the top. In a thought bubble above the architect he wrote: “You should wear a hat to hide the fact you are going bald and a top coat to hide that tie.” To which Guerrero responds: “While I still know one, would you like the name of my barber?” It’s not known if he shared the photograph with Wright, but the architect would surely have enjoyed the exchange.

Wright and Guerrero, Pleasantville, New York, 1949. Thought bubbles drawn by Guerrero depict an imagined, humorous exchange between the architect and photographer. ©2018 Pedro E. Guerrero Archive

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, “Section.” The Quarterly is a member-exclusive benefit. Visit our Membership page to learn about other member benefits.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emily Bills is an educator, author, and curator. She is faculty at Woodbury University where she coordinates the Urban Studies Program in the College of Liberal Arts. Emily has contributed essays to several books on architectural and urban history, including Michigan Modern: Design That Shaped America (Gibbs, 2016) and Visual Merchandising: The Image of Selling (Ashgate, 2016). Emily’s book California Captured about Los Angeles-based architectural photographer Marvin Rand was recently released by Phaidon Press. Some of her curatorial projects include exhibitions on Wayne Thom, Catherine Opie, William F. Cody, Héléne Binet, and Pedro E. Guerrero, including a recent exhibition at the New Canaan Historical Society. Emily has received fellowship and grant support from the Smithsonian, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation. Her book Linking Up Los Angeles: How the Telephone Built a City is forthcoming from the University of Pittsburgh Press.