Reading Broadacre

Jennifer Gray | Oct 1, 2018

On April 15, 1935, in the heart of Rockefeller Center in New York, Frank Lloyd Wright mounted an exhibition featuring a radical project called Broadacre City, in which he proposed to resettle the entire population of the United States onto individual homesteads. A veritable Trojan horse that challenged the very urbanity of the space where it was exhibited, Broadacre City advanced an idea of decentralization whereby communities would be based on small-scale farming and manufacturing, local government, and property ownership.

Conceived at the height of the Great Depression, Wright never intended to build Broadacre City but rather used it as a vehicle to address pressing social, economic, and environmental issues, many of which have contemporary relevance. His vision invites us to reflect on questions of our own time, such as the role of government, social and economic equality, infrastructure and sustainability, and how to foster community.

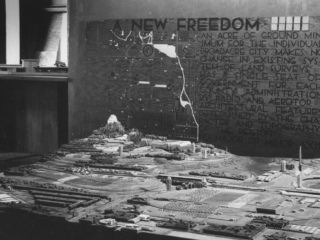

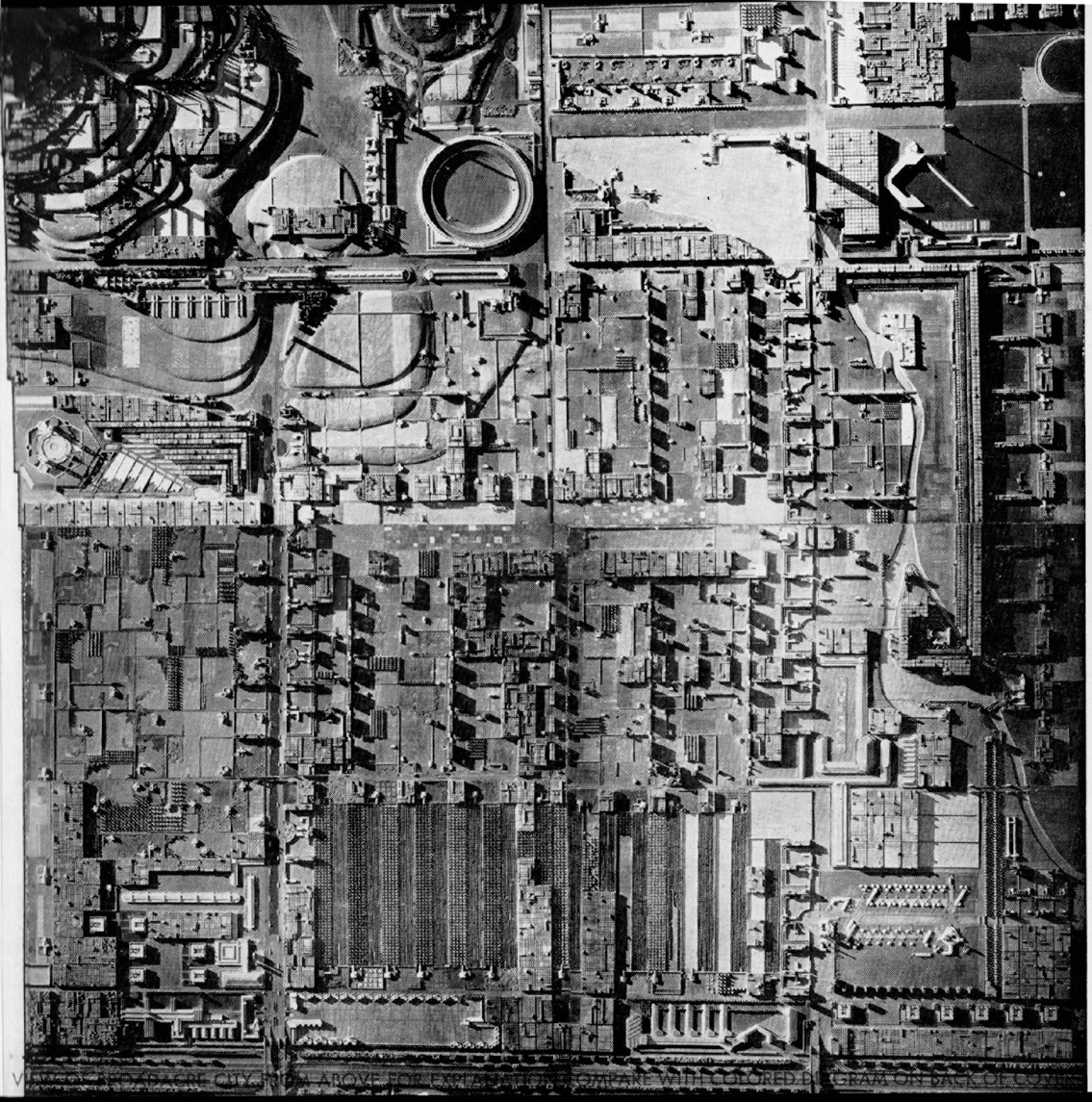

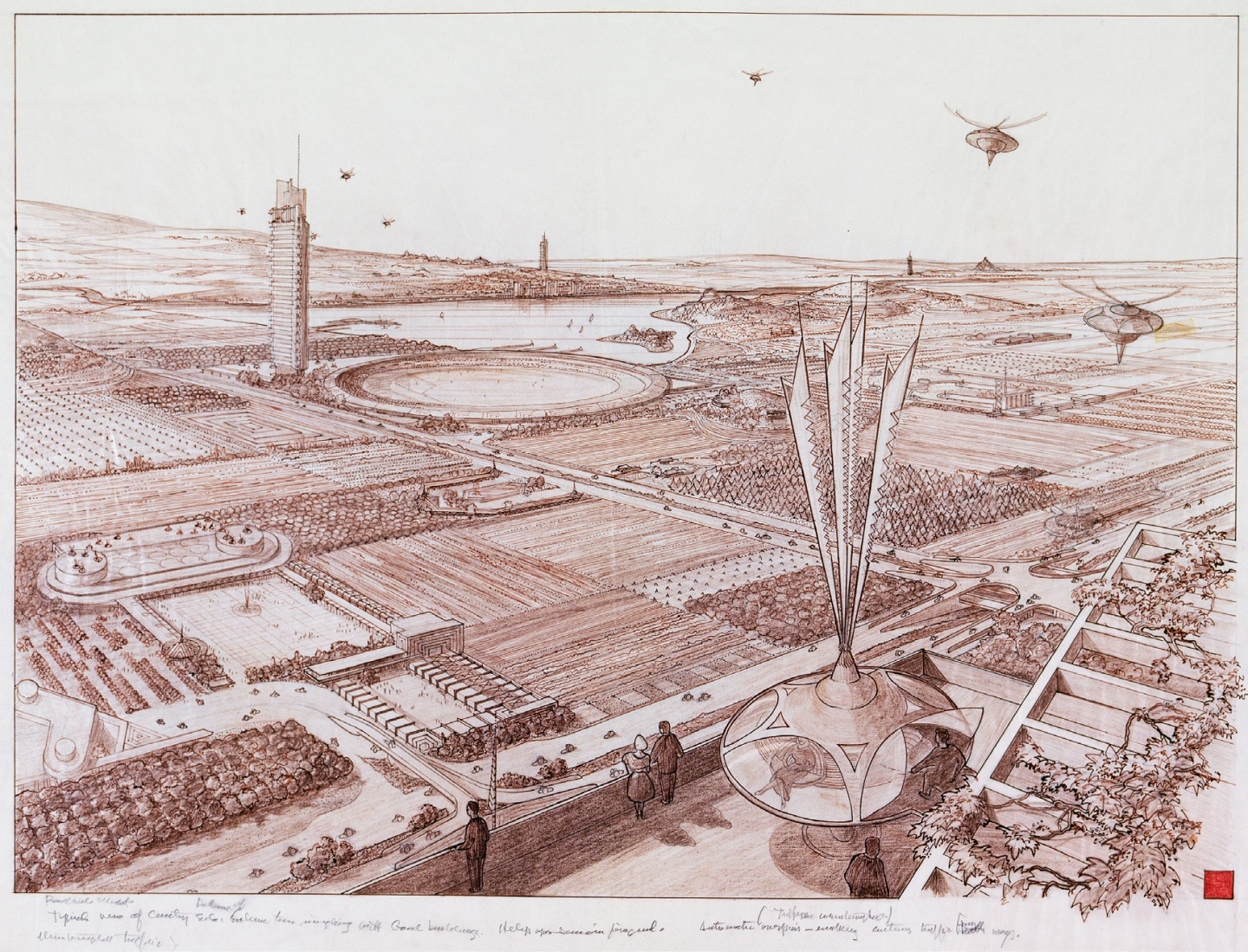

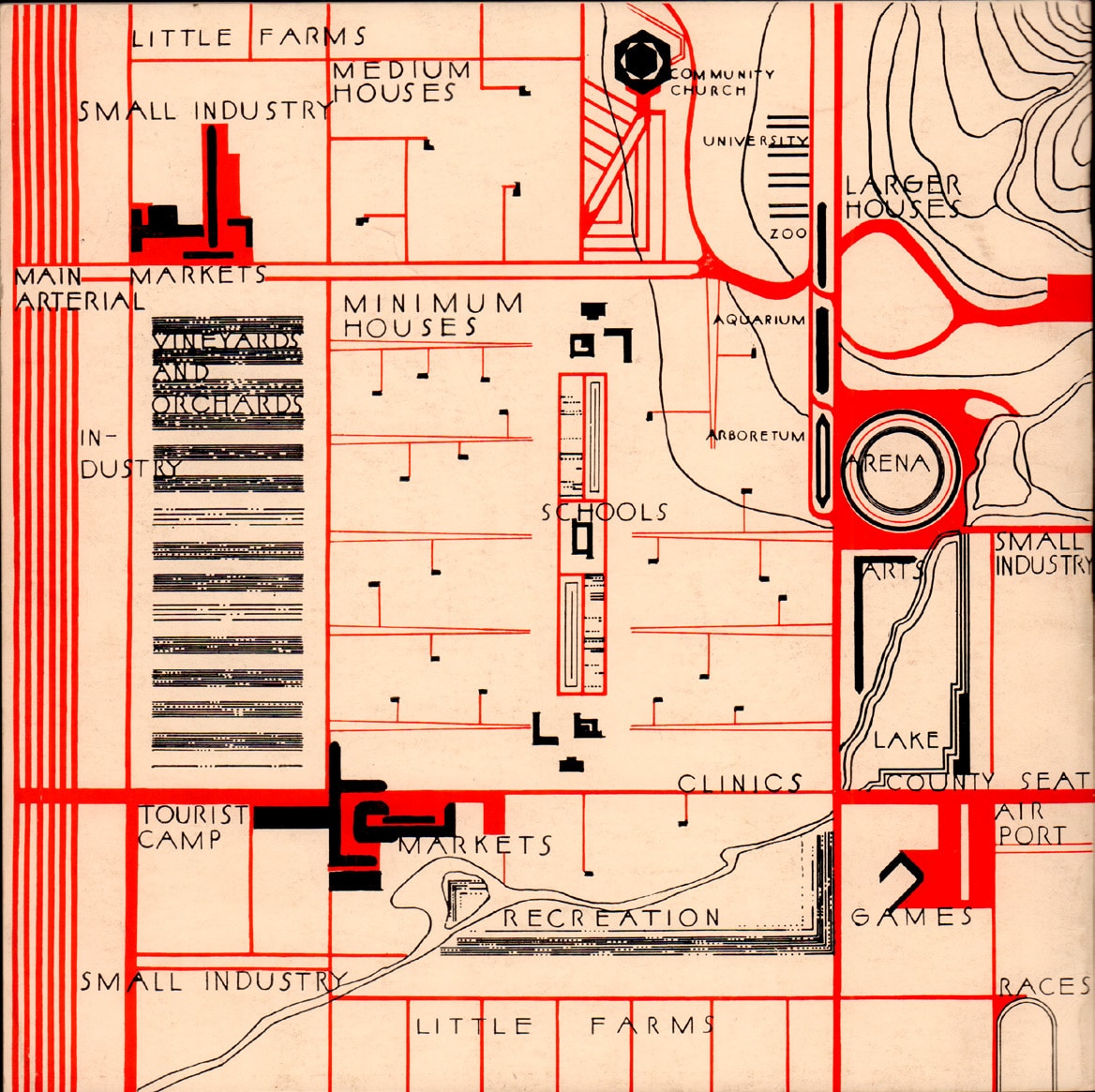

The Broadacre City exhibition was sponsored by the National Alliance of Art and Industry, a Rockefeller-funded initiative that endeavored to educate the public about advances in American industry. Its centerpiece was a 12-foot by 12-foot model that represented 4-square miles of “typical countryside” accommodating 1,400 families. Within this radius, all elemental units of modern society were included: farms, factories, offices, schools, parks and recreational spaces, places of worship, a seat of government, and individual houses [Fig. 1 and Fig. 2]. The scale was local, as Wright emphasized: “…little farms, little homes for industry, little factories, little schools, and a little university.” Every citizen of Broadacre was a property owner—a minimum of one acre of land, or more according to need—and also owned at least one car, as transportation was primarily by automobile. Wright envisioned that the low-density community represented in the Broadacre model would be replicated across the United States, creating a network of small communities that would be connected together by highways and telecommunication systems, such as radio and telephone [Fig. 8].

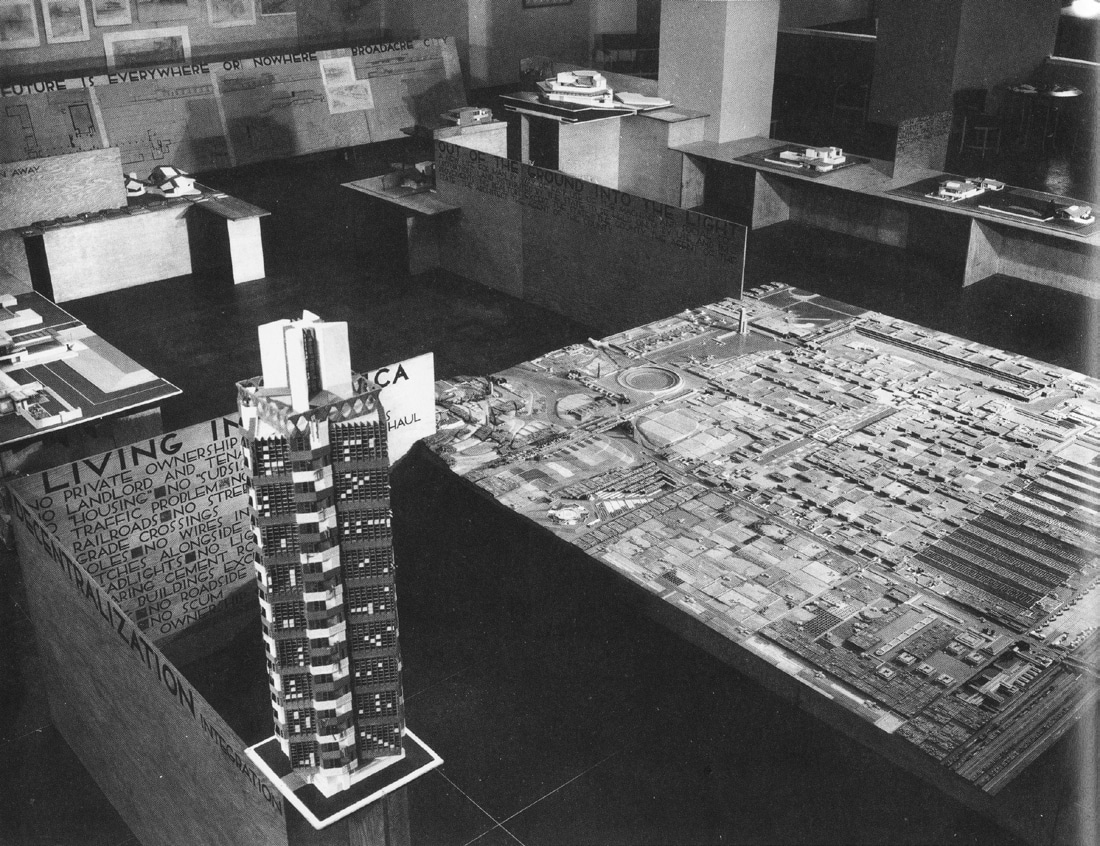

Accompanying the Broadacre model were smaller models of individual projects, drawings, and text panels that together told the story of Wright’s utopian vision [Fig. 3]. At the entrance, a panel introduced the overall theme of Broadacre: DECENTRALIZATION INTEGRATION. Once inside the installation, various other didactic panels outlined the main arguments. THE FUTURE IS EVERYWHERE OR NOWHERE points to the sweeping nature of Wright’s proposal. OUT OF THE GROUND INTO THE LIGHT speaks to the agrarian ideal behind Broadacre, with its tapestry of small farms and privately owned land. Below this, further explanation:

A NEW WAY FOR MAN BY WAY OF FAIR USE OF THE MACHINE AND SOCIAL COORDINATION ■ LAND DISTRIBUTED BY THE STATE TO BE HELD ONLY BY USE AND IMPROVEMENTS ■ NO REALTORS EXCEPT THE STATE ■ THE COUNTY THE AGENT OF THE STATE ■ THE ARCHITECT THE AGENT OF THE COUNTY

FIGURE 1. Photo by Skot Weidemann.

Broadacre model.

FIGURE 2

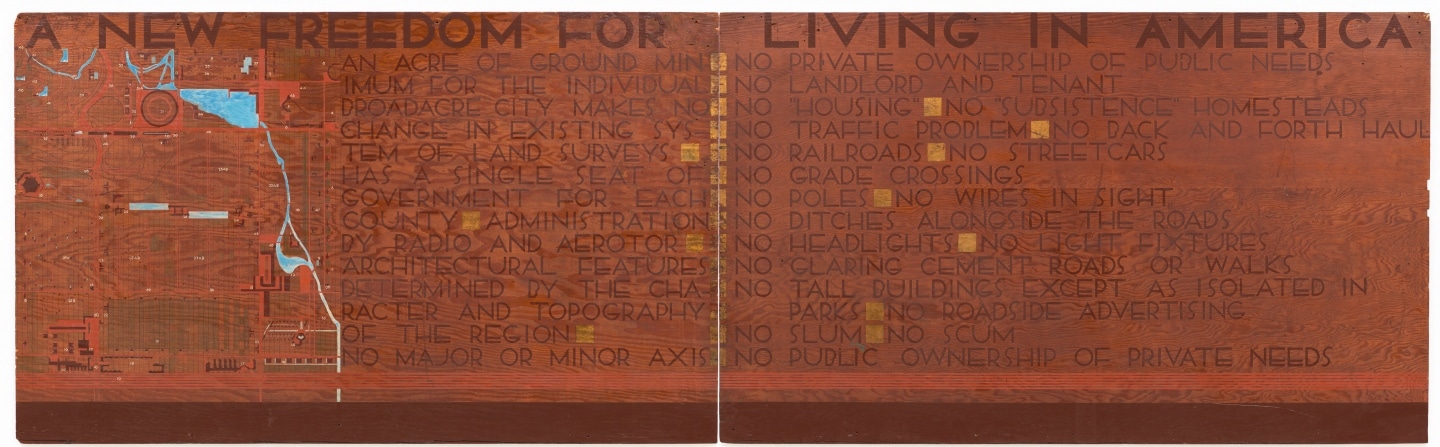

The argument culminated in two adjacent panels titled A NEW FREEDOM FOR LIVING IN AMERICA where Wright enumerated key points in list form [Fig. 6 and Fig. 7]:

NO PRIVATE OWNERSHIP OF PUBLIC NEEDS NO LANDLORD AND TENANT

NO “HOUSING” ■ NO “SUBSISTENCE” HOMESTEADS

NO TRAFFIC PROBLEM ■ NO BACK AND FORTH HAUL

NO RAILROADS ■ NO STREETCARS

NO GRADE CROSSINGS NO POLES ■ NO WIRES IN SIGHT NO DITCHES ALONGSIDE THE ROAD

NO HEADLIGHTS ■ NO LIGHT FIXTURES

NO GLARING CEMENT ROADS OR WALKS NO TALL BUILDINGS EXCEPT ISOLATED IN PARKS

NO ROADSIDE ADVERTISING NO SLUM ■ NO SCUM

NO PUBLIC OWNERSHIP OF PRIVATE NEEDS NO MAJOR OR MINOR AXIS

FIGURE 3

FIGURE 4

FIGURE 5

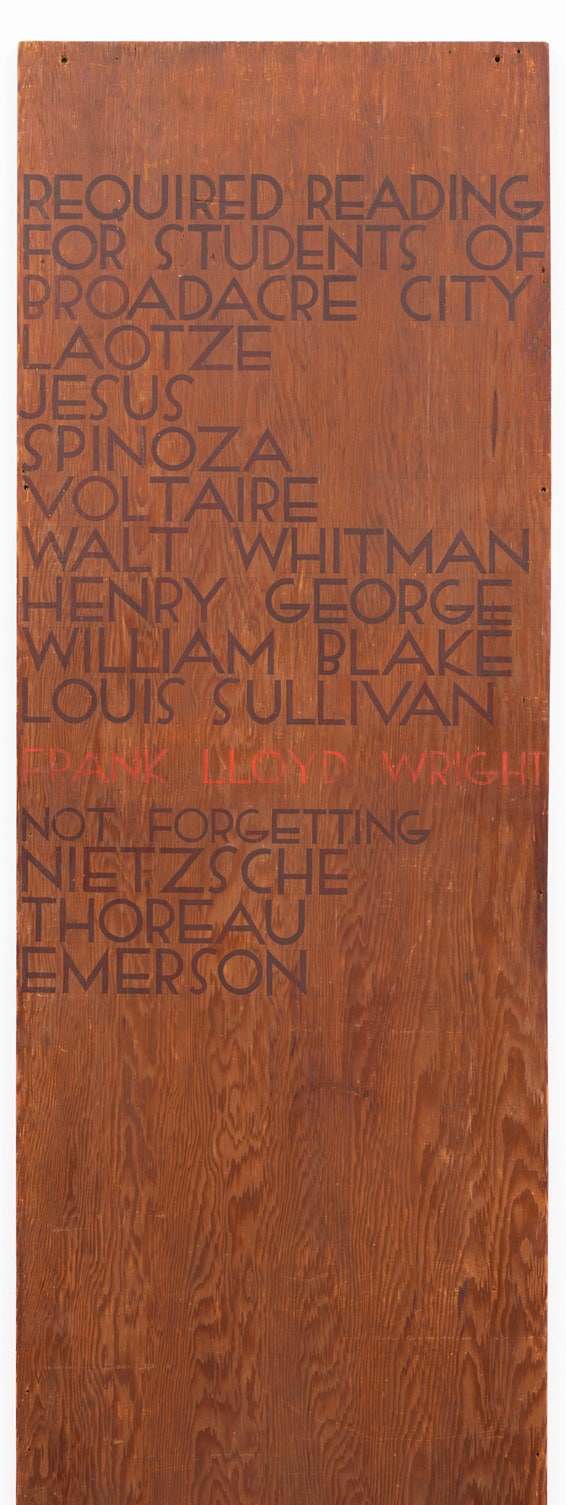

Inscribed as they are with polemics and provocations, these demountable plywood panels operate as a kind of portable wall text or catalogue, allowing us to read Broadacre as a social and political position as much as an urban plan. When we unpack them, we see that Wright contextualized Broadacre within a larger discourse that was sounding the alarm about the social, economic, and environmental problems created under capitalism at the turn of the twentieth century. Two additional panels provide clues. These vertical markers offer a kind of bibliography to students of Broadacre and included in the list of names are notable activists and critics of laissez-faire capitalism, such as Henry George, Edward Bellamy, and Thorstein Veblen [Fig. 4 and Fig. 5]. These reformers were concerned about a broad range of questions related to capitalism, especially the labor exploitation and economic and social inequality that seemed to result from industrialization. There is not space enough here to flesh out all the connections between Broadacre and the “REQUIRED READING” listed on these panels, but we can sketch a few major directions.

Like many progressive reformers, Wright was troubled by the human cost of industrialization under capitalism—monotonous work, exploitation, the widening gap between the rich and poor, and so forth—and argued that the machine could solve such problems if used humanely. He imagined that the efficiencies of machine production could reduce the average workday by half—freeing up large amounts of time for the citizens of Broadacre to pursue their own interests—while still producing the goods necessary for modern life. Wright had advanced similar arguments as early as 1901 in his lecture “The Art and Craft of the Machine,” but he also echoed ideas expressed by Edward Bellamy in 1888 in the bestselling, utopian science fiction novel, Looking Backward. Bellamy imagines a future society set in the year 2000 in which the problems created by industrialization and capitalism are solved through social coordination. For example, the state owns and manages all production to ensure that the goods of society are equally distributed to its citizens; working hours, especially for menial jobs, are drastically reduced; and everyone retires with full benefits. For Wright, consumption was as much a part of the problem as production, an idea advanced in 1899 by Thorstein Veblen in his seminal text The Theory of the Leisure Class. Writing about Broadacre decades later in 1940, Wright still criticized society for its obsession with consuming goods, which perpetuated the dehumanizing cycle of endless production and labor exploitation: “Let’s face it…what we have is commercialization—not civilization.” Symbols of the “commercial conquest of this continent” abounded, according to Wright, in the form of railroads, advertisements, and poles and wires for power and telephone lines—the very targets of his attack in the panels dedicated to A NEW FREEDOM FOR LIVING IN AMERICA.

How does Wright propose to remedy these problems in Broadacre City? Borrowing ideas on land value from Henry George, Wright makes land ownership a universal right in his utopia—NO LANDLORD AND TENANT. George had published a groundbreaking, and bestselling, study on poverty and inequality in 1879 called Progress and Poverty, in which he argued that landowners and monopolists were able to accumulate disproportionately large amounts of wealth because they earned money by charging rent or interest to others, what he called “the unearned increment,” and not through their own productive labor. To minimize “rent” in Broadacre, every citizen was a property owner and obliged to use or improve her land, not hold it in reserve for speculation. Neither banks nor the government could threaten an individual’s homestead. Owners could use it as their residence, but also as a place of business or to grow their own food, thus ensuring their economic independence. The security that land ownership conferred, Wright argued, solved the problems of unemployment and labor exploitation because subsistence was certain and thus workers were empowered to reject disagreeable labor.

FIGURE 6 (LEFT) + FIGURE 7 (RIGHT)

Wright also proposed to retool the monetary system to reduce even further the amount of rent in Broadacre. Credit would be socialized, created and controlled by the State for defense, public works, and all social services. A “National Dividend” would replace relief programs and social security, while a controlled “Just Price” would replace market determinations for all necessary goods. In this way, according to Wright, “money will become a medium of exchange, of distribution, and not a commodity in the hands of private firms to be let out on hire.” Wright derived many of his ideas about monetary reform from a Swiss economist named Silvio Gesell, also honored on the Broadacre panels, who himself was a follower of Henry George. Gesell, whose writings were enjoying a revival in the 1930s, proposed a form of perishable currency, whereby banknotes issued at the beginning of the year would lose a fixed percentage of its face value by the end of the year. Since this money effectively lost value, not unlike perishable goods, it would discourage capital accumulation and thus reduce interest, or “rent on money,” as Wright called it.

Such sweeping changes demanded that Wright rethink the role of government. First, it was vital to eliminate politics from government. “Politicians dare not really lead,” Wright argued, since they were more concerned about negotiating “money miracles” on behalf of interest groups that only maintained the status quo in order to get reelected. To this end, each county in Broadacre had just one minor government, the “county seat,” which worked directly with the national government. Because this arrangement was local and direct, it encouraged public participation in the political process and thus was arguably more democratic. Wright further limited the powers of the State to the business administration of social necessities only where private interests ceased to function effectively: NO PRIVATE OWNERSHIP OF PUBLIC NEEDS / NO PUBLIC OWNERSHIP OF PRIVATE NEEDS. Services such as fire and police protection, banking and money, construction and maintenance of shared infrastructure, and mail delivery were among the public needs that Wright conceded to government. But the most important power of the State was in its capacity as realtor. Land, the backbone of wealth and freedom in Broadacre, was distributed by the State with the assistance of the county architect. This would have amounted to a major redistribution of wealth along socialist lines even as it conferred an inordinate amount of power to the architect, prompting one historian to dub Broadacre an “architocracy.”

FIGURE 8

Broadacre map.

It is perhaps worth pointing out that most of the social and political theories Wright referenced in Broadacre—the REQUIRED READING list—originated in the late nineteenth century, not during the Great Depression when Broadacre was conceived. Wright insisted that citizens of his utopia must work and use their own faculties rather than “sitting around waiting for their own government to feed them, think up jobs for them, pat them on the back or put them in the workhouse.” This indictment of New Deal programs and the emerging welfare state—the historical context of Broadacre itself—is made more complicated by the fact that Wright claimed to be completely loyal and sympathetic to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “vain endeavor” to save the capitalist system. Indeed, the Broadacre exhibition toured to Washington, D.C., with the expressed aim of advancing Wright’s ideas to the President in the hopes of securing the architect a planning job with the Resettlement Administration to design greenbelt towns. Moreover, Wright clearly is not anathema to nationalizing the resources of the country. How can this be reconciled? One possibility is that the social and economic programs advanced by Roosevelt in the 1930s did not go far enough to satisfy Wright. They were progressive patches to ameliorate the problems of a capitalist system left mostly intact. Wright’s vision was much more radical. He implied as much when he described Broadacre as an entirely new mode of living: “New form, not reform, is our fundamental need in America.”

So, what can Broadacre teach us today? Though the logic of late capitalism differs from its previous expressions, we find ourselves facing similar questions. How can we address the widening gap between the rich and the poor? How can we reform government to better meet our collective goals? How can we overcome our differences to create fair and inclusive communities? In the 1930s, critics lambasted Broadacre as simultaneously communist, fascist, and socialist. Others seized upon its impossibility, as an urban plan or social organization. More recently, historians have pointed to the inherently unequal and racist presumptions underlying any system based on private property given its barriers to entry, now and in the 1930s. Wright himself admitted, “…as for craft, state-craft is not my craft.” Whatever its shortcomings, however, Broadacre is remarkable as a thought experiment. Wright attempted to grapple with the most challenging and intractable questions of his time, questions that linger today. We may disagree with his answers, but I would like to suggest that it is the questions, not the solutions, that make Wright of continued relevance to our own time.

This article originally appeared in the winter 2018 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine, “Perspective.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Editors Note: Dr. Jennifer Gray is now the Director of the Taliesin Institute. This post was published in 2018. At that time Dr. Gray was Curator of Drawings and Archives at Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. She studies modern architecture, with an emphasis on how activists and designers used architecture, cities, and landscape to advance social and spatial justice at the turn of the 20th century. She co-curated Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive at The Museum of Modern Art, New York.