Revisiting Frank Lloyd Wright’s Vision for “Broadacre City”

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Sep 8, 2017

As early as the 1920s, Frank Lloyd Wright began to regard his architectural work as an integral part of a larger concept which he called Broadacre City. This new democratic city, as envisioned by Wright, would take advantage of modern technology and communications to decentralize the old city and create an environment in which the individual would flourish. Here, we briefly discuss Broadacre City and the forces that shaped Wright’s thinking at the time of its creation. Included are the personal recollections of Cornelia Brierly, one of Wright’s first apprentices.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 1991 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly.

In the fall of 1934 Frank Lloyd Wright was addressing the Taliesin Fellowship at Spring Green with potential client Edgar J. Kaufmann sitting by his side. According to former apprentice Edgar Tafel who recounts the episode in his book “Years With Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius,” Wright began expounding on his theory for the salvation of America—a new city based on the automobile—Broadacre City.

“Mr. Wright declared that if he could, he would create an exhibit of models and drawings of Broadacres and send the message all over the United States,” Tafel said. “E.J. (Kaufmann) asked, ‘What would it take to produce such an exhibit?’ Mr. Wright replied without hesitation, ‘$1,000.’ E.J.: ‘Mr. Wright, you can start tomorrow.’ We started tomorrow.” In less than a year the models were ready for display.

Broadacre City model, January 1, 1935.

More than 55 years have passed since the first public exhibition of the Broadacre City models. The large (12′ x 12′) model of Broadacre City and ten collateral models made their first appearance as the centerpiece of a National Alliance of Arts and Industry Exposition at Rockefeller Center on April 14, 1935. Tafel accompanied the model to New York City where more than 50,000 people examined Wright’s plans for a new American city.

Exhibitions continued in the United States through 1939. The model later toured Europe (France, Germany, Switzerland, Holland and Italy) and Los Angeles from 1950 through 1954. Upon its return to Taliesin in Wisconsin, Wright mounted the model for display at Hillside where he continued to perfect and edit it until the time of his death in 1959.

The model has most recently been transferred to the Avery Fine Arts and Architectural Library at Columbia University and The Museum of Modern Art, where it is being studied as part of MoMA’s “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive.”

In the fall of 1989 Arizona State University’s College of Architecture and Environmental Design began planning to create a second model of Wright’s Broadacre City as part of “Arizona Celebrates Frank Lloyd Wright 1990-1991,” an 18-month statewide series of special programming focusing on Wright’s life and work. At that time Dean John Meunier wrote: “Urban, and suburban development in America today is in crisis, theoretically and in practice. Lack of any meaningful theory of urban land use that has wide acceptance, combined with unrestrained private development activity, has led to the destruction of urban life, the deterioration and abandonment of inner cities and the creation of urban sprawl.

“Inapplicable to current problems as Wright’s Broadacre City may have appeared in the 1930s, it offers today a tool with which a new critique of modern American urban form may be devised …. (M)odern urban theory, so called, has proven incapable of describing urban reality in our time, let alone ameliorating its conditions. What is needed more than theory is a reintroduction of value, and it was in just that area that Broadacre City had its strength. As Wright well knew, only when values are put first will technology become tool rather than master.”

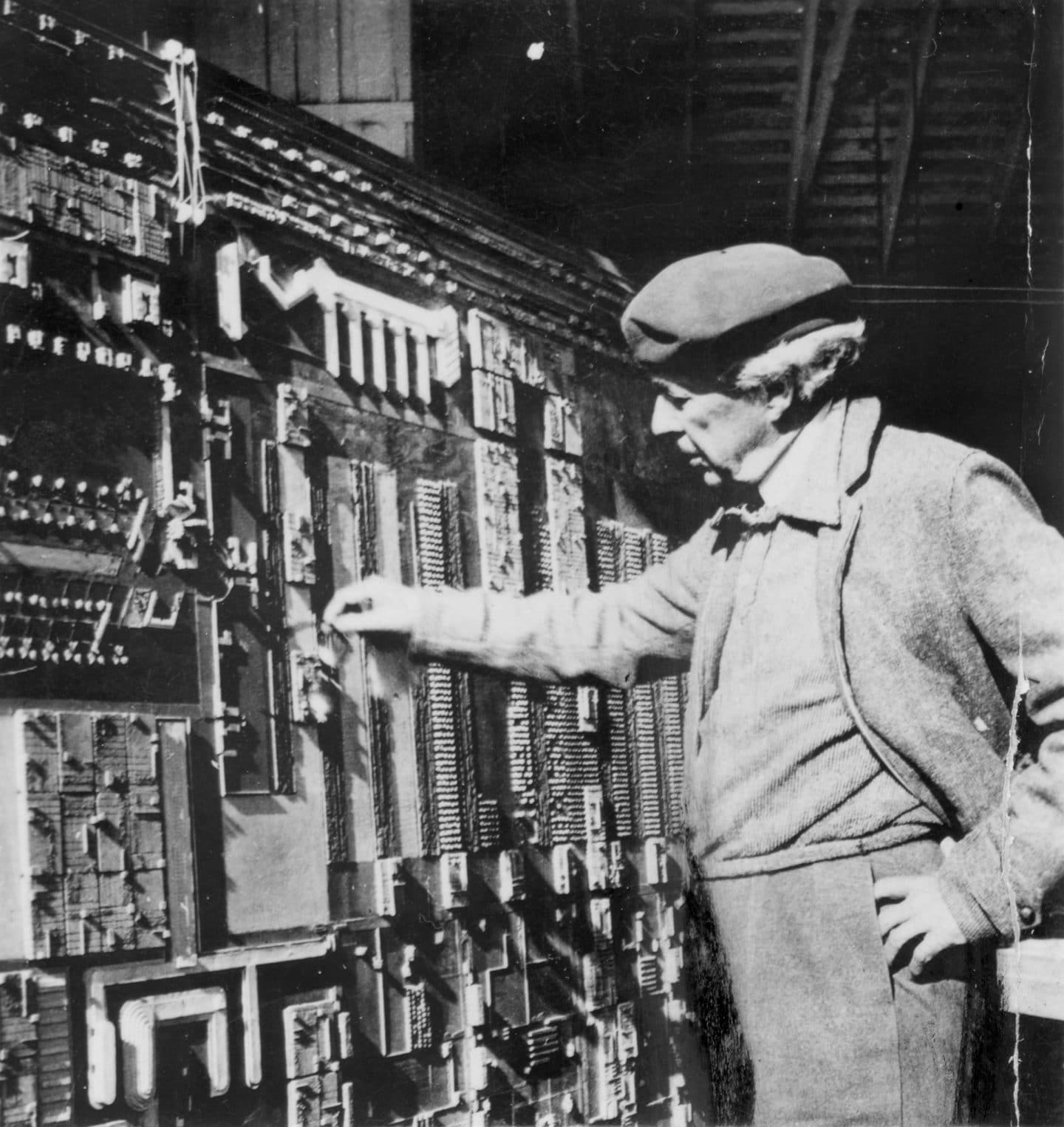

Wright inspecting Broadacre City model, January 1, 1935.

Wright’s vision for Broadacre City had been developing for many years, especially during the 1920s when Wright’s almost complete lack of commissions provided him with an opportunity to develop new concepts.

According to Tafel, “To the public and to the rest of the profession, by the late 1920s, Mr. Wright’s practicing career seemed finished because his personal difficulties bore so heavily on his work. At the age of sixty, he was looked upon as the grand old man of architecture—a sharp tongued critic, but a voice from a past era. While the mainstreams of architecture were busy designing, building, publishing, and creating their artistic controversies and revolutions, Frank Lloyd Wright began to think out new ideas.”

Many scholars agree there can be no doubt of the central significance of Broadacre City to the last 30 years of Wright’s architectural output. Wright always argued that good architecture developed out of a profound appreciation of the life and times, the practices and ideals of the society in which the architect lived.

According to Lionel March in “Writings on Wright,” Broadacre City was Wright’s attempt to give architectural and urban form to the democratic ideas and social actions of his American contemporaries, people such as the American pragmatists William James and John Dewey; the popular economist Henry George; the American institutional economists Thorstein Veblen and John Commons; the Wisconsin political progressives such as the LaFolettes and others including Jane Adams and Richard Ely.

“Most of what Wright says about society can be traced to the work, writings and actions of these men and women,” March said. “It is clear from his own writings and those of his contemporaries that he did not consider democracy to be a form of government so much as a way of living.”

March maintains that “perhaps the most pragmatic fact about Wright’s contribution to architectural theories of urban form is that he accepts that, first and foremost, a city is not an arrangement of roads, buildings and spaces, it is a society in action. The city is a process, rather than a form.”

Thus, in Broadacre City, Wright set about to provide, on a community scale, for the expression of democratic ideas as he saw them. His city would provide the space, freedom and beauty necessary for the growth of the individual.

Where the old city was seen as the result of impersonal forces that had diminished people’s dignity and possibilities for growth, the new democratic city would take advantage of modern technology and communications to decentralize the old city and its concentrations of power and unearned privilege.

In place of absentee ownership, Broadacre City proposed individual ownership of one’s home, farm and place of employment. In place of corporate ownership, Broadacre City proposed public ownership of the utilities of common necessity: power, transportation, mediums of exchange. Instead of “rent on land, money, and ideas” determining the course of development of the city, Broadacre City proposed that the community and the artist have a greater role in the design of the built environment.

In studying the models one of the most obvious characteristics of Broadacre City is that it contains many small farmsteads and houses intermingled. Virtually every freestanding house has some agricultural land attached to it. During the Depression era of the 1930s, Wright was not the only person to theorize that if people had a plot of land, however small, they would be able to subsist.

In describing Broadacre houses Wright said, “They would be especially suited in plan and outline to the ground, where they would make more of gardens and fields and nearby woods than now, insuring perpetual unity in variety …. All that Broadacre houses ask of society is that they be genuinely Democratic, and of all government that it be strictly impersonal. This city of the future does, however, ask for a quality of thought and a kind of thinking on the part of the citizen that organic architecture alone at the present time represents or seems to understand … a new reality in our way of living and building, an environment in our democracy.”

“Perhaps the most pragmatic fact about Wright’s contribution to architectural theories of urban form is that he accepts that, first and foremost, a city is not an arrangement of roads, buildings and spaces, it is a society in action. The city is a process, rather than a form.”

Anthony Puttnam, a Taliesin Architect who worked with Wright, believed that “Broadacre City challenges us to understand what we mean by a democracy and how it might be expressed by a city. Contemporary urban America often by its physical makeup seems indifferent to the plight of the majority of its people and shows a similar indifference to the environment, education, community and beauty. Broadacre City proposes a physical fabric and social arrangement necessary to achieve the broader values of democracy. However we may debate the practical application of Broadacre City, we can not ignore its challenge.”

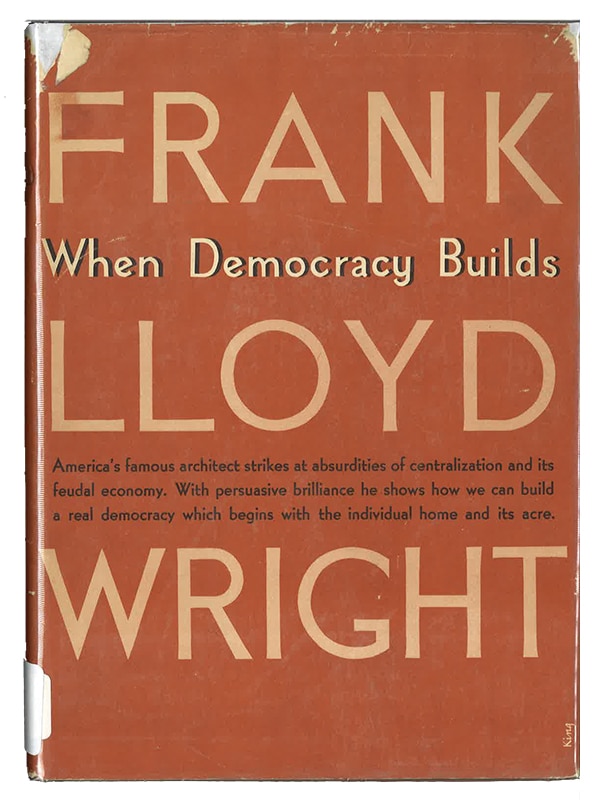

Wright’s ideas of decentralized planning were presented in his book “Disappearing City” written in 1932. In 1945 the University of Chicago Press published the book “When Democracy Builds” which was a revision of the first book but illustrated by Broadacre City models. In 1958 Wright extensively revised and expanded the two books into a new book entitled “The Living City.”

Broadacre City was never realized. However, until his death in 1959 Wright addressed in individual projects the architectural and community design concepts he envisioned as the natural expression of the new city—moderate cost housing, community and public facilities, commercial and manufacturing buildings—all designed to enhance life—each to be a center of beauty and excellence. Among these are: the Marin County Civic Center (a rural county administration complex); The Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma (the modified version of the apartment towers from Broadacre City) the Johnson Wax Administration Building (a space where the worker can experience dignity); and the Usonian Automatic house.

Today Broadacre City provides a framework to look at city planning as a question of man’s relationship to the built environment, with the message from Wright that, “The American citizen must abandon his favorite expedients—especially the idea that money plus authority can rule the world. He must realize that ideas inspired by spiritual integrity will make the modern world.”

Building a City

“The city should be everywhere and nowhere.” That, according to Cornelia Brierly, is how Frank Lloyd Wright described his concept for Broadacre City—a new type of city that would flow across the landscape changing with the terrain and needs of the individual citizen.

Cornelia was just 22 when she and 20 other apprentices to Frank Lloyd Wright began to build the 12 foot square Broadacre City model in Chandler, Arizona. The year was 1935—the Taliesin Fellowship’s first winter in Arizona.

The group had just completed their cross-country trek from Wisconsin driving in a caravan of cars and trucks loaded with bounty from the gardens of Taliesin. As guests of Dr. Alexander Chandler, the Fellowship stayed at La Hacienda, a polo stable that had been converted into living quarters. It was there under the entry roof that the Broadacre City models were constructed.

Fellowship in Arizona, April 1, 1935.

“Mr. Wright was right there showing us what to do, laying it out and working on the highway system,” Cornelia said. “It was very serious work but we were in the sun, we were young and we were having a wonderful time, despite the fact that our food supply from Wisconsin had dwindled and we were living much of the time on peanut butter, salt pork and sauerkraut.

“Mr. Wright saw this idea as extending out over the land and that it would assume different characteristics depending on the terrain. The main thing was to have an architect that understood building in relation to the site and who understood the needs of the people.”

“We each had our own specialty when we worked on the model,” Cornelia added. “Don Thompson was an engineer and he worked on the intersections with Mr. Wright. I worked on the small houses that had orchards and vineyards behind them. I started painting my section in earth tones, which Mr. Wright liked. Later he decided the whole model should be colored that way.”

According to Cornelia, Frank Lloyd Wright believed that cities were archaic and outmoded. “With today’s modern technology, transportation and communications systems, Mr. Wright felt that there was no longer any need for people to huddle together in cities as they did in the dark ages. He felt that the whole idea of space was so important-that people should be out in the air and light.” The idea was to give each person at least one acre of land on which to raise his own food. “Stewardship of the land gave one dignity,” she said.

One of Wright’s most ambitious ideas for Broadacre City was its transportation system, Cornelia said. “There were separate lanes for cars and trucks with a monorail in the center. Under the roads were large warehouses where the trucks could unload their cargo, letting smaller trucks distribute the freight throughout the local area.”

According to Cornelia, Wright was intent on eliminating the “back and forth haul.” He provided housing for factory workers above the factories with land for tilling nearby. Professionals would work at home. “He was trying to devise a system where people could spend more time with their families and not so much time traveling unnecessarily.” Broadacre City also featured a model farm, a gas station, a model skyscraper, model homes, farm markets, a county seat (which would be the governing entity), schools, theaters, etc .

The large model was completed within a few months and then trucked to Rockefeller Center in New York City. Later, Cornelia accompanied the model to a showing at the Kaufmann Department Store in Pittsburgh and then to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. “I talked to several hundred people everyday,” Cornelia said. “Engineers were particularly fascinated by the highway system.

“Mr. Wright saw this idea as extending out over the land and that it would assume different characteristics depending on the terrain. The main thing was to have an architect that understood building in relation to the site and who understood the needs of the people.”