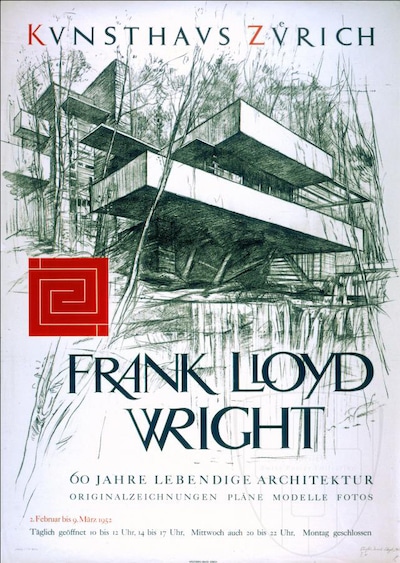

Wright on Exhibit: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architectural Exhibitions

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Apr 14, 2017

Kathryn Smith discusses the creation of her book “Wright on Exhibit: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architectural Exhibitions.”

More than one hundred exhibitions of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work were mounted between 1894 and his death in 1959. Wright organized the majority of these exhibitions himself and viewed them as important to his self-presentation as his extensive writings. He used them to introduce his new work, appeal to a wide audience, and persuade his detractors. Wright on Exhibit presents the first history of this neglected aspect of the architect’s influential career.

Drawing extensively from Wright’s unpublished correspondence, Kathryn Smith challenges the preconceived notion of Wright as a self-promoter who displayed his work in search of money, clients, and fame. She shows how he was an artist-architect projecting an avant-garde program, an innovator who expanded the palette of installation design as technology evolved, and a social activist driven to revolutionize society through design. While Wright’s earliest exhibitions were largely for other architects, by the 1930s he was creating public installations intended to inspire debate and change public perceptions about architecture. The nature of his exhibitions expanded with the times beyond models, drawings, and photographs to include more immersive tools such as slides, film, and even a full-scale structure built especially for his 1953 retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum. Placing Wright’s exhibitions side by side with his writings, Smith shows how integral these exhibitions were to his vision.

Lloyd Lewis House model, 1939-40 (Courtesy Don Kalec)

Top-turn intersection model, 1934-35

Q: What is different about Wright on Exhibit than other books you have written about Wright?

Kathryn Smith: I chose his architectural exhibitions during his lifetime because it was a finite subject that had real clarity and purpose. It provided a great framework to view how Wright favored his own work, how he prepared it in drawings and models, and how he dealt with the press, museums, the public, and contemporary architects. I live in Los Angeles, the location of the Getty Research Library, where Wright’s correspondence of 103,000 letters and documents are on deposit on microfiche. By 2016, I would say that I had read about 15,000 pieces of this correspondence. I knew his voice and his moods. I wanted that to come through to the reader by quoting the correspondence. It was one of my main purposes: to put the reader as much as possible into the moment.

Q: How many exhibitions are in your final count?

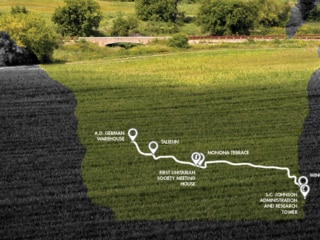

KS: My total is 124 exhibitions. There is a gap between 1915 and 1929. But from 1930 forward, there were at least one or more exhibitions–one man shows or surveys–every year until his death where my book stops.

I created two appendices: the list of all of the exhibitions and an illustrated catalogue raisonné of all known models, extant or lost. Even the list of models is staggering. There are 57.

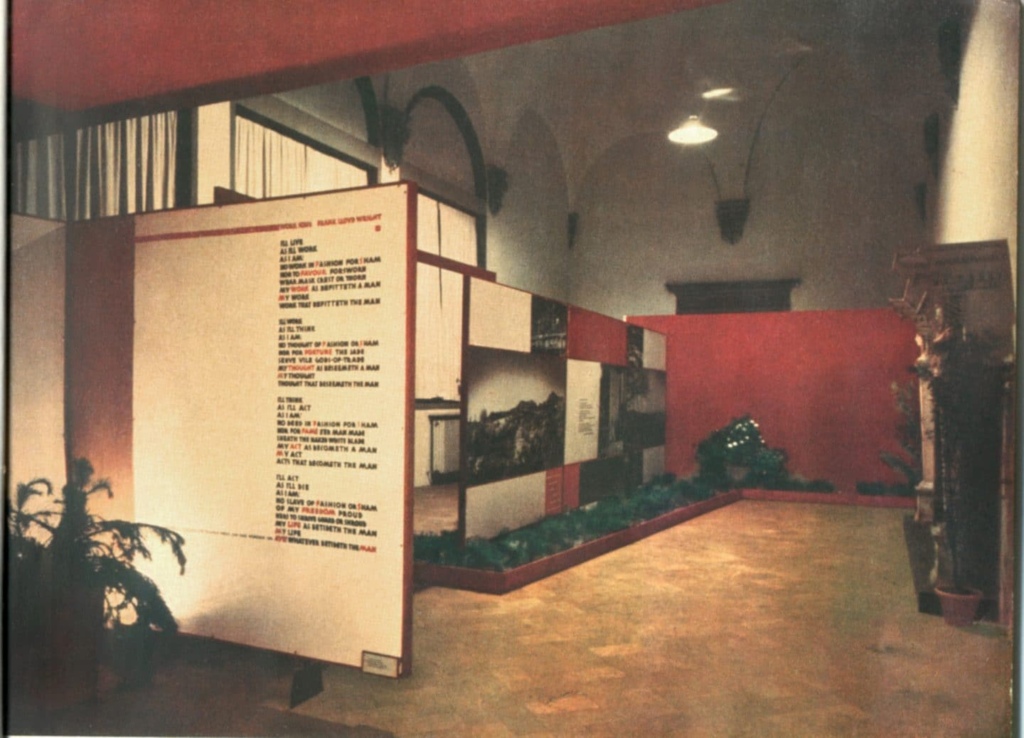

Wright exhibition, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, Italy, 1951 (Photograph by Ancellotti and Co.)

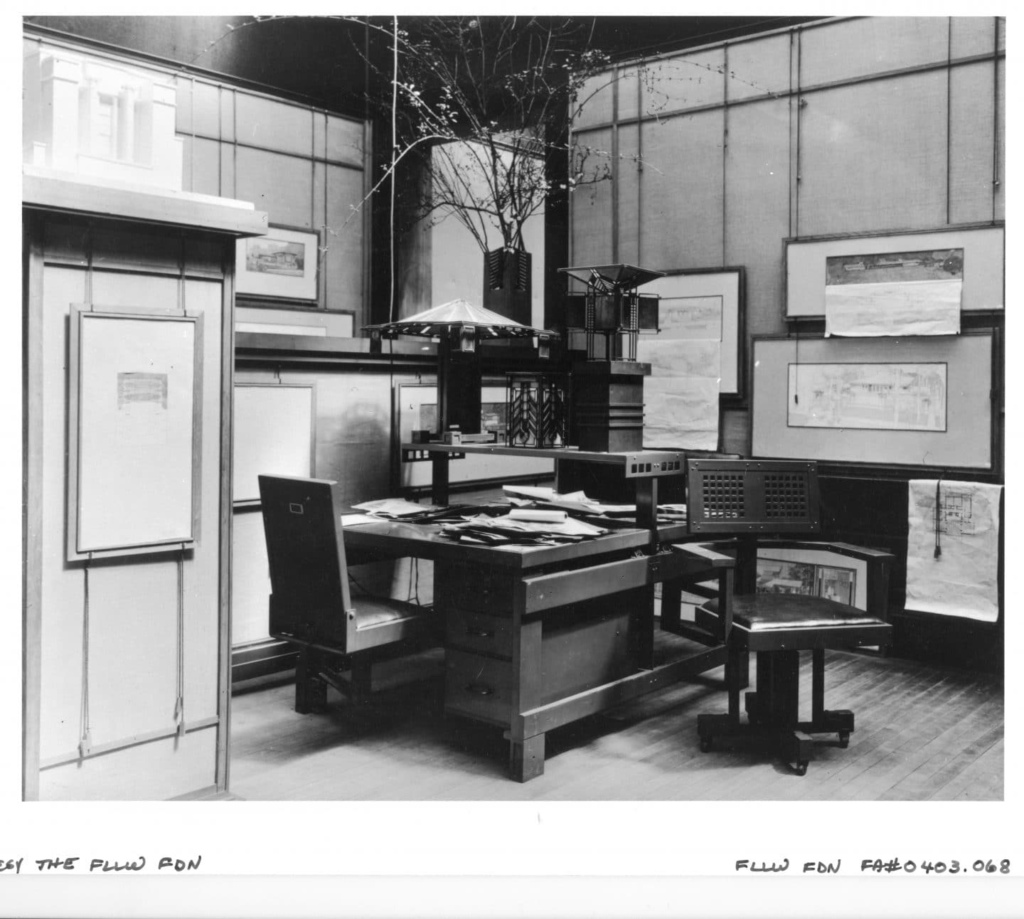

Chicago Architectural Club exhibition, 1907

Q: The excerpts from letters are vivid, but how did you illustrate the book?

KS: I was lucky because Wright clearly wanted to document his career. Beginning in 1907, he hired professionals to photograph his installations. I accumulated a good representation of black and white images of all the major exhibitions. But I learned that the shows themselves were rich in color. It was imperative to communicate this richness to the reader. The book has 57 color illustrations, primarily of drawings, and 188 half tones.

Q: Did you make any discoveries that surprised you?

KS: Yes, quite a few. I would say that there is a very vague outline in the mind of many people who have heard of the major exhibitions. They conjure up basically either positive or negative impressions. But that changes dramatically when the factual history is traced. For instance, “Sixty Years of Living Architecture” was conceived in Florence, Italy in 1948 and went through the most torturous three-year period of failed international diplomatic planning. Wright was completely ignorant of this activity. Yet, it finally opened due to the determination, the effort, and the financial support of a few individuals, American and Italian. It is a very compelling story, complete with cliffhangers. Almost all the major exhibitions I wrote about were dramatic with Wright threatening to pull out at the last minute.

Q: What was the most memorable thing you learned about Wright?

KS: After the openings came the reviews. In some years, especially, before 1948, when there were a number of mixed or negative assessments, he felt downhearted and baffled. In truth, he had a rather thin skin. His most characteristic response was to turn to writing: he lashed out in anger at the critics. What I was struck by was Wright’s vulnerability. There were quite a few instances of negative criticism when he seemed to stand aside, like an outsider, not comprehending why the American people did not embrace him as their champion as he intended. It is true, he became a “starchitect,” in the parlance of our day; but he was looking for recognition of greater depth.