Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unbuilt Skyscrapers Come to Life with Never-Before-Seen 3D Imagery

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Jan 23, 2023

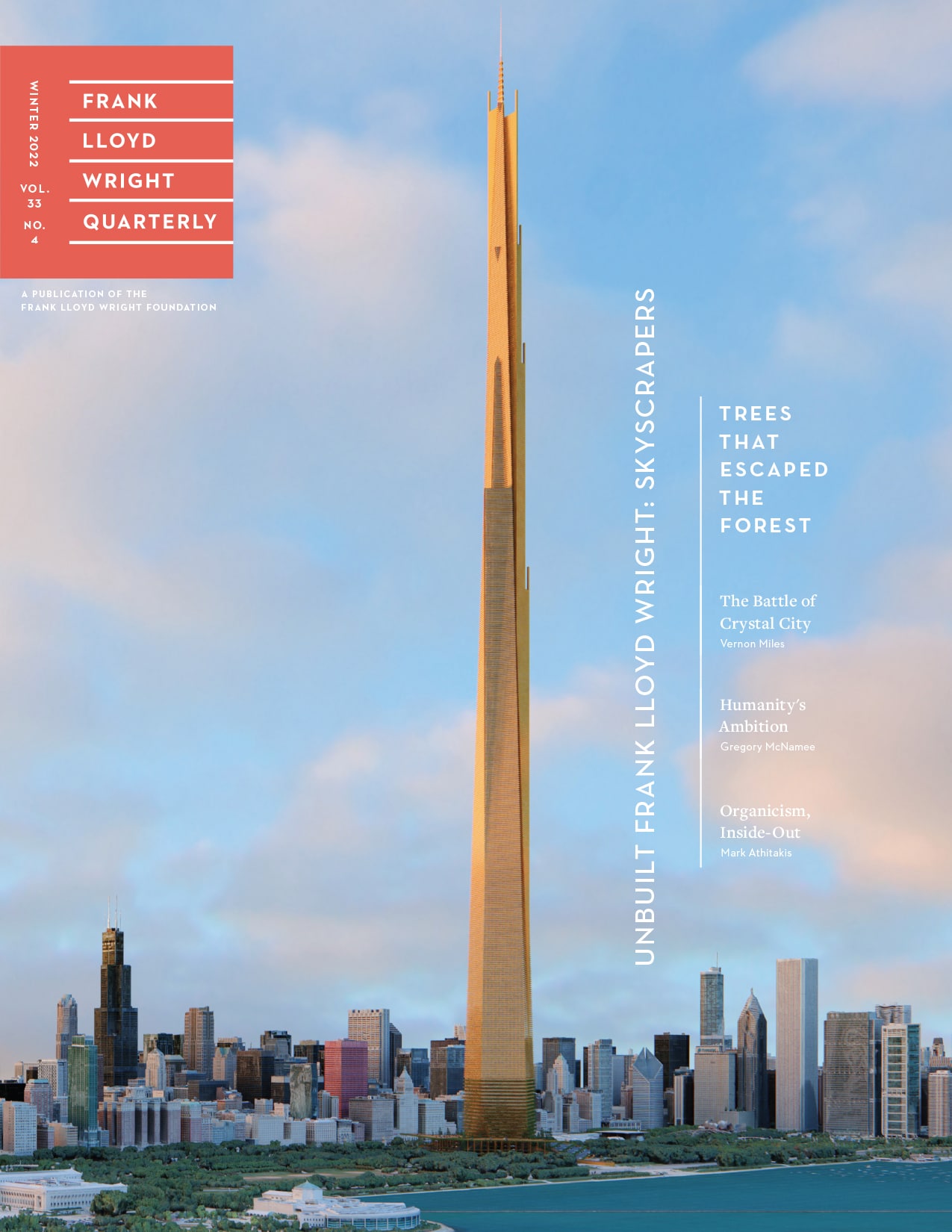

Latest Issue of The Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly Features an Inside Look at Three Sky-High City Structures with Photorealistic Renderings by Spanish Architect David Romero

Today, Wright enthusiasts have an opportunity to see what might have been, thanks to computer-generated, 3D images by Spanish architect David Romero, who uses advanced techniques of 3D representation to create striking “photorealistic” renderings that are so highly detailed they appear to be contemporary photography. The latest issue of The Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, a hard-copy magazine for Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation members, focuses on three of Wright’s spectacular unbuilt, sky-high structures, featuring the stories behind each project and never-before-seen renderings by Romero.

While Wright voiced criticism of skyscrapers over the years, he remained fascinated by the possibilities of taller buildings in novel forms, and was once quoted as saying, “Towers have always been erected by humankind—it seems to gratify humanity’s ambition somehow and they are beautiful and picturesque.”

Here are some highlights of the three key designs featured in the Quarterly:

National Life Insurance Building (Chicago)

Chicago has long laid claim to being the birthplace of the skyscraper. After the boom years of the 1920s led to a surge in building projects across Chicago, Wright hoped to be part of the city’s push to higher elevations with his National Life Insurance Building.

The client was the company’s president, Albert M. Johnson, who was willing to pay a $20,000 flat fee to Wright for his efforts. The project was to be one of his most beautiful and breathtaking: a 25-story glass fortress, intended to be constructed on Chicago’s North Michigan Avenue, composed of four identical wings with sophisticated copper panels.

In contrast to other major office buildings being erected at the time with historic revival details, renderings of the National Life Insurance Building show an edifice that’s very modern for its time in its use of light materials as a curtain wall, maximizing daylight and natural ventilation that had been important to Chicago School architects for decades.

Ground level rendering of the National Life Insurance Building (David Romero/ Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation)

While not as famous as Wright’s other unrealized skyscraper project in Chicago — the Mile High from 1956 — it not only would have changed the city’s skyline forever, but it also would have served as a tribute to his mentor, Louis Sullivan, who had spent his entire career committed to experimental new architecture. If given the opportunity, Wright might have followed Sullivan’s example of finding creative and organic solutions to advancing the possibilities of the steel frame.

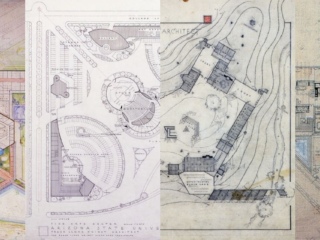

Crystal City (David Romero/ Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation)

Crystal City (Washington, D.C)

In late 1940, Wright was hired to design a new development in the heart of what would become Washington, D.C.’s Kalorama neighborhood. The project, widely known as Crystal City, was an example of mixed-use development decades ahead of its time, but a dramatic series of clashes with the city’s zoning authorities would see it relegated to one of the architect’s great unrealized works.

The project was spearheaded by a local group of developers led by Roy S. Thurman, who chose a semi-forested clearing called the Dean Tract as the site. Thurman’s earliest discussions about the project, even before Wright was brought on board, indicated it would include a hotel, apartments, a shopping center, garages, a theater and an auditorium.

Unfortunately, what wasn’t included in Thurman’s communications with Wright was any information on D.C.’s strict height and use limits. The Dean Tract was zoned residential with a city-wide height limit of 90 feet for residential buildings. That limit was only slightly higher for commercial buildings, at 110 feet.

Without any knowledge of the zoning limitations, Wright moved forward with a design capable of housing the diversity of uses Thurman envisioned for the site and more, including building heights ranging from 140 to 260 feet. The result was a series of towers linked together in a U shape, with “entrance towers” at the ends and the heights of towers at the bend in the U scaling up to between 16 to 18 stories.

Thurman, meanwhile, mostly kept Wright in the dark about the battles over their project, until the National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCPPC) ultimately voted unanimously to oppose the project, bringing it to a halt.

The Illinois rendered into Chicago (David Romero/ Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation)

The Illinois (Chicago)

In 1956, Wright held a small press conference to announce a gleaming new tower project in Chicago. The Illinois was set to be 528 stories and stand a mile high, four times as tall as the world’s tallest building at the time. “The Empire State Building would be a mouse by comparison,” Wright boasted.

At more than 18 million square feet, three times the floor space of the Pentagon, the Illinois would contain space for more than 100,000 people, for which reason Wright dubbed it “a city in the sky.” Four major highways, along with rail lines and a heliport, would provide access to the building, with docking space for more than 100 aircraft and parking space for more than 15,000 cars.

Getting people to the top of the building would be the task of 76 elevators, each with five-story-high cabs delivering passengers to five floors at a time. These elevators would be atomic-powered, and, Wright said, run at a mile a minute—three times faster than the fastest elevators today.

Wright’s rough design for the Illinois reflected that of trees with deep taproots, with an antenna-line central structure out of which four wing-like buttresses with cantilevered floors would extend. The “taproot” was a 15-story deep substructure that looked something like an upside-down Eiffel Tower, out of which the central concrete-and-steel core would rise.

Outside the core, as if to elaborate on Wright’s principle of “construction from within outward rather than from outside inward,” the building would be made of a steel frame, the material best suited for high rises, with concrete floors. Wright knew that steel towers tend to sway to varying degrees in the wind, but believed that his tower, rooted so deeply into the ground, would withstand the oscillation.

Wright never had the chance to test his theory. Despite the innovative design, Wright had no site, no client, and no budget for the Illinois. A later curator of materials concerning the Illinois concluded that the earlier press conference had been only “an incredible attention-getting thing.”

The Illinois (David Romero/Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation)

Had the Illinois ever been built according to Wright’s larger plan as the centerpiece of his Broadacre City, which embraced a swath of urban, suburban, and rural zones, it would have been so massive that no other towers would have been needed in the vicinity.

Many of you who have followed the Whirling Arrow blog over the years have seen various stories that feature David’s illustrations depicting unbuilt Frank Lloyd Wright buildings. In 2017’s Architect gives new life to Frank Lloyd Wright’s demolished and unbuilt work we interviewed David about his thought process of how he goes about creating photorealistic computer renderings. Another post Unbuilt Frank Lloyd Wright Works Come to Life in Quarterly Magazine David shares some of his behind-the-scenes work with computers used to create these stunning works of art.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE QUARTERLY

To be among the first to see stories and images like those featured in this issue of The Quarterly, subscribe to the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine by becoming a member.

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation members receive the Quarterly as part of their membership benefits. The Quarterly offers readers an innovative look into the past, present, and future of Frank Lloyd Wright’s legacy through thoughtful graphic and written explorations of the legendary architect’s work and the community it has created. Become a member to start receiving your copy of The Quarterly and receive amazing content like that featured here.