An Architecture of Mobility: The Lake Tahoe Project

David De Long | Sep 21, 2020

In 1923 Frank Lloyd Wright began designing plans for a non-commissioned and unbuilt project, the Lake Tahoe Summer Colony. Here, not only does he imagine an array of cottages along the shore, but also a fleet of cabins afloat in the bay.

Photorealistic renderings by David Romero

During the 1920s, in a series of remarkable projects, Frank Lloyd Wright explored new geometries and incorporated an ever-expanding landscape. The Tahoe Summer Colony (1923) reflects these changes, with the lake itself an essential component of his concept. Yet there is no record of an actual commission. Instead, he seems to have initiated the commission on his own, hoping to draw the owner of the land into some sort of partnership. Lacking new work at the time, he had taken a similar course with his Doheny Ranch development that same year.

Wright located his proposal for Lake Tahoe on a site of some 200 acres surrounding the head of Emerald Bay, at the lake’s southwest corner. Heavily-wooded mountains provided a sense of enclosure, their slopes enlivened by natural terraces edged with boulders, and by spring-fed rivulets and waterfalls. An island near the center of the bay added picturesque focus. The land was owned by Jessie Armstrong, whose father had acquired the property in 1892. It was undeveloped except for a grouping of small cabins that had been built by a previous owner in the 1880s.

How Wright was drawn to the site is not known. It may have been through connections to Los Angeles attorney Frank P. Dearing, who had been involved with land acquisitions for the Armstrong family. He and Wright may have considered forming a company to develop the site; Jessie Armstrong would supply the land, Wright would contribute his designs, and an investor would provide capital. But Wright needed no prompting to be drawn to sites of spectacular beauty and was likely drawn to the site on his own. However his interest came about, in 1923, while supervising construction of La Miniatura, he traveled from Los Angeles to Tahoe City, where he would have taken one of the lake’s elegant steamers to a stop near Emerald Bay. There he was met by Jessie Armstrong, who ferried him to her land in the family’s small boat. She later recalled that he “had even begun to form his plans for how he would develop the property if this company took it over.”

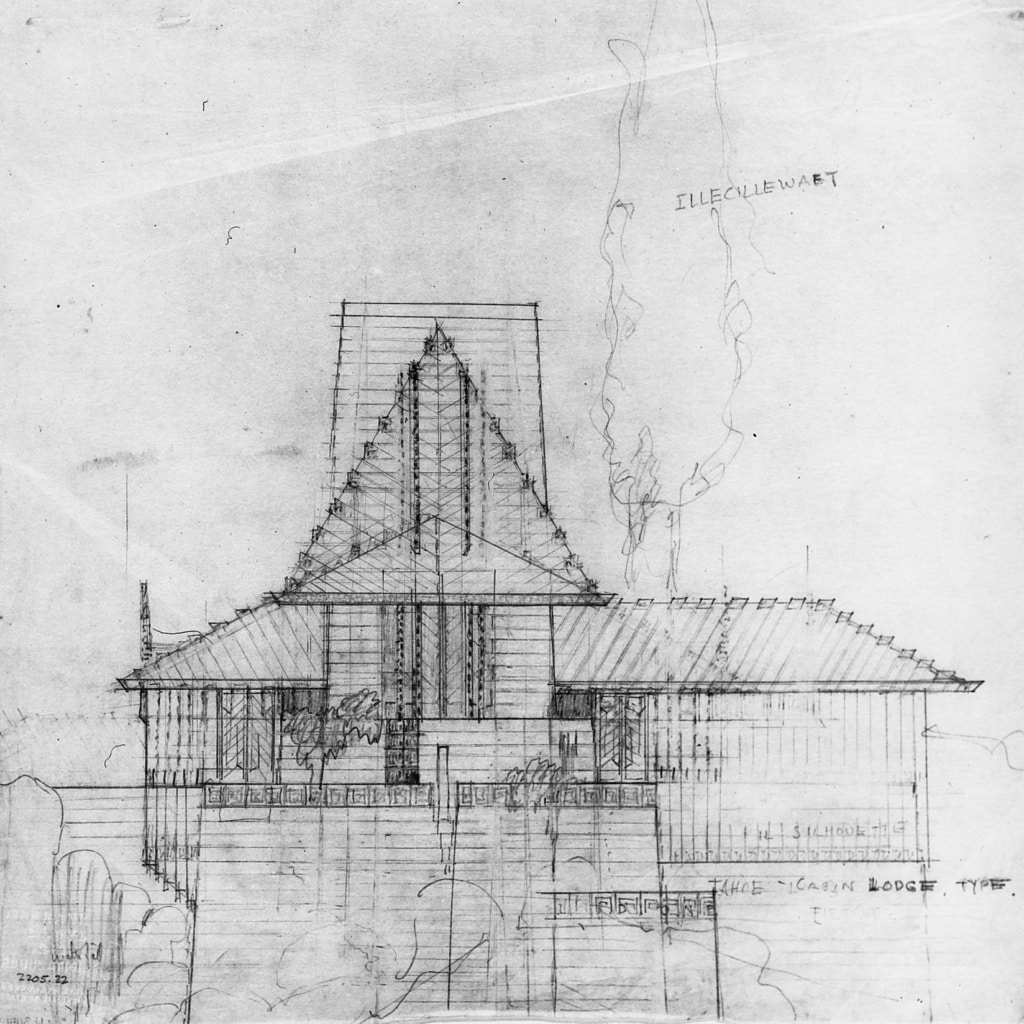

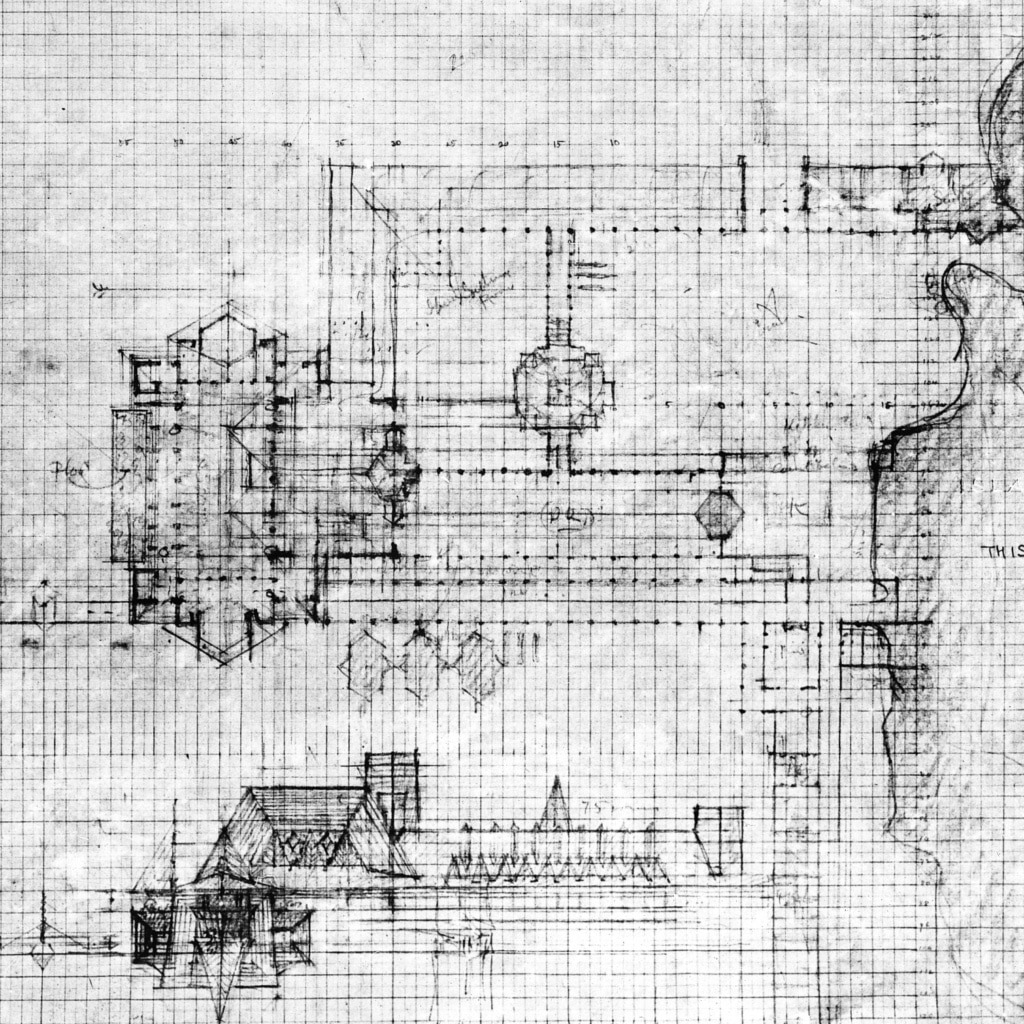

LODGE TYPE

archival perspective

LODGE TYPE

archival elevation

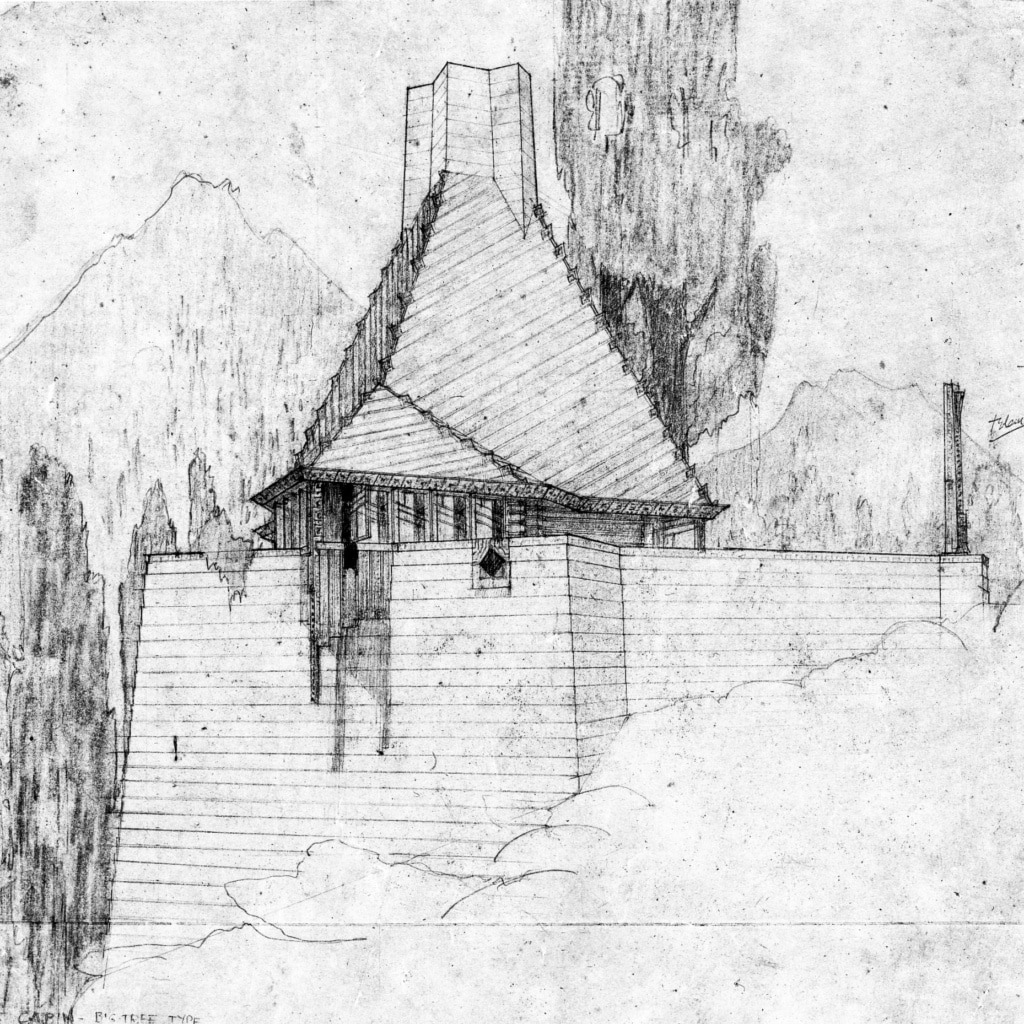

WIGWAM

archival perspective

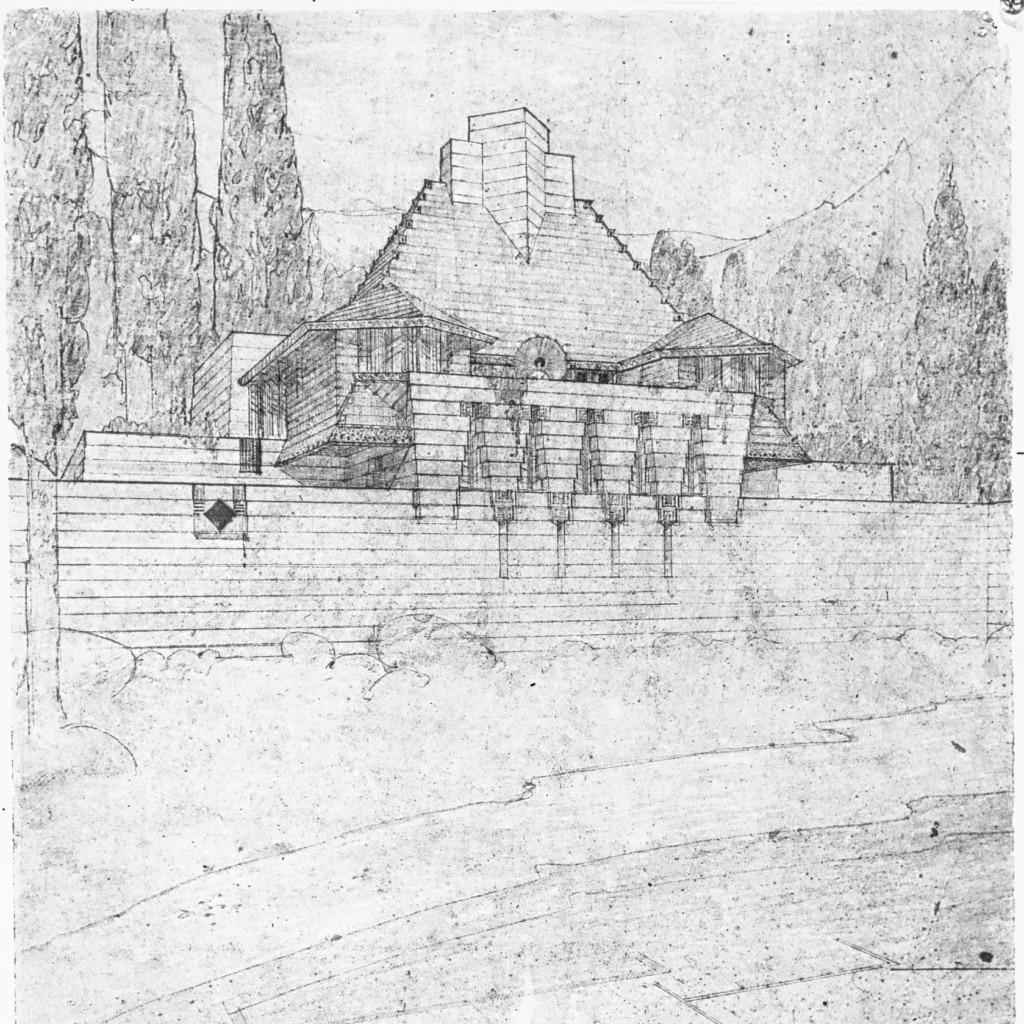

SHORE TYPE

archival perspective

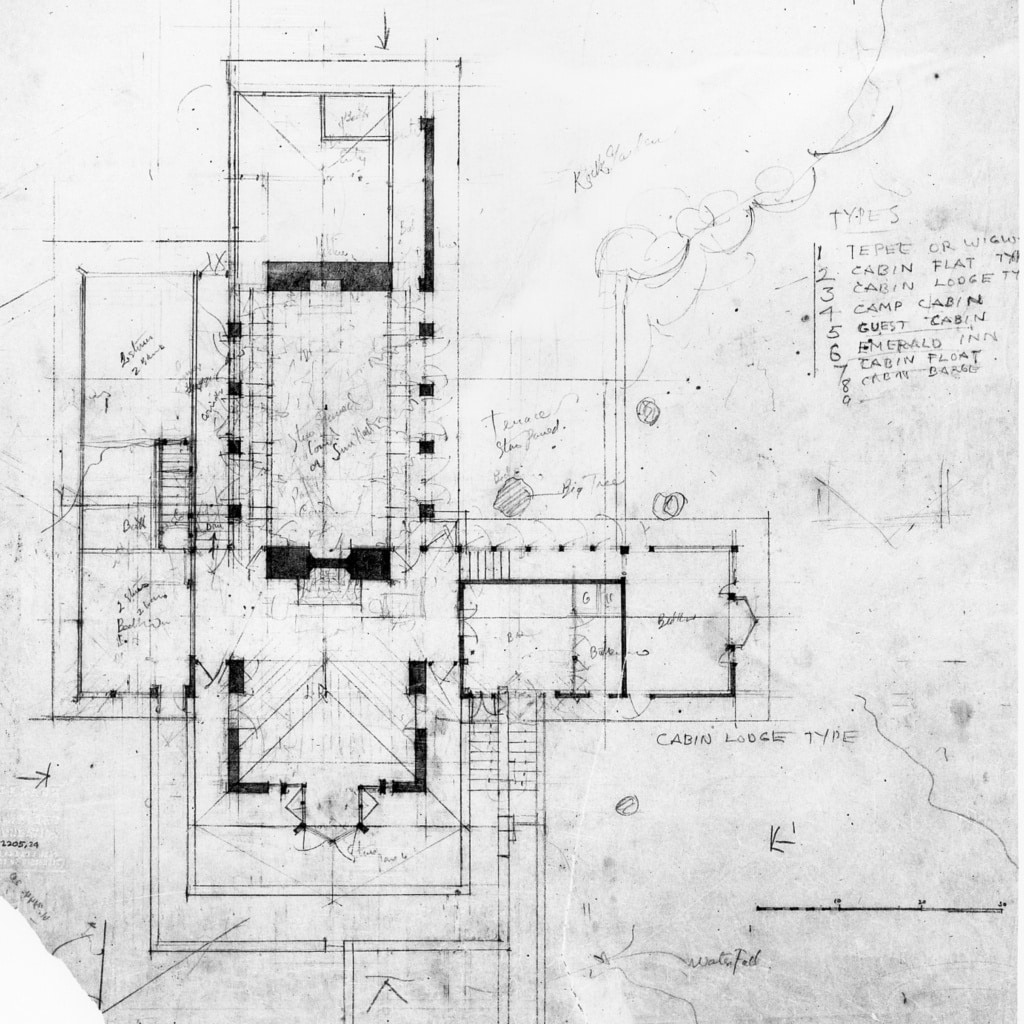

LODGE TYPE

archival plan

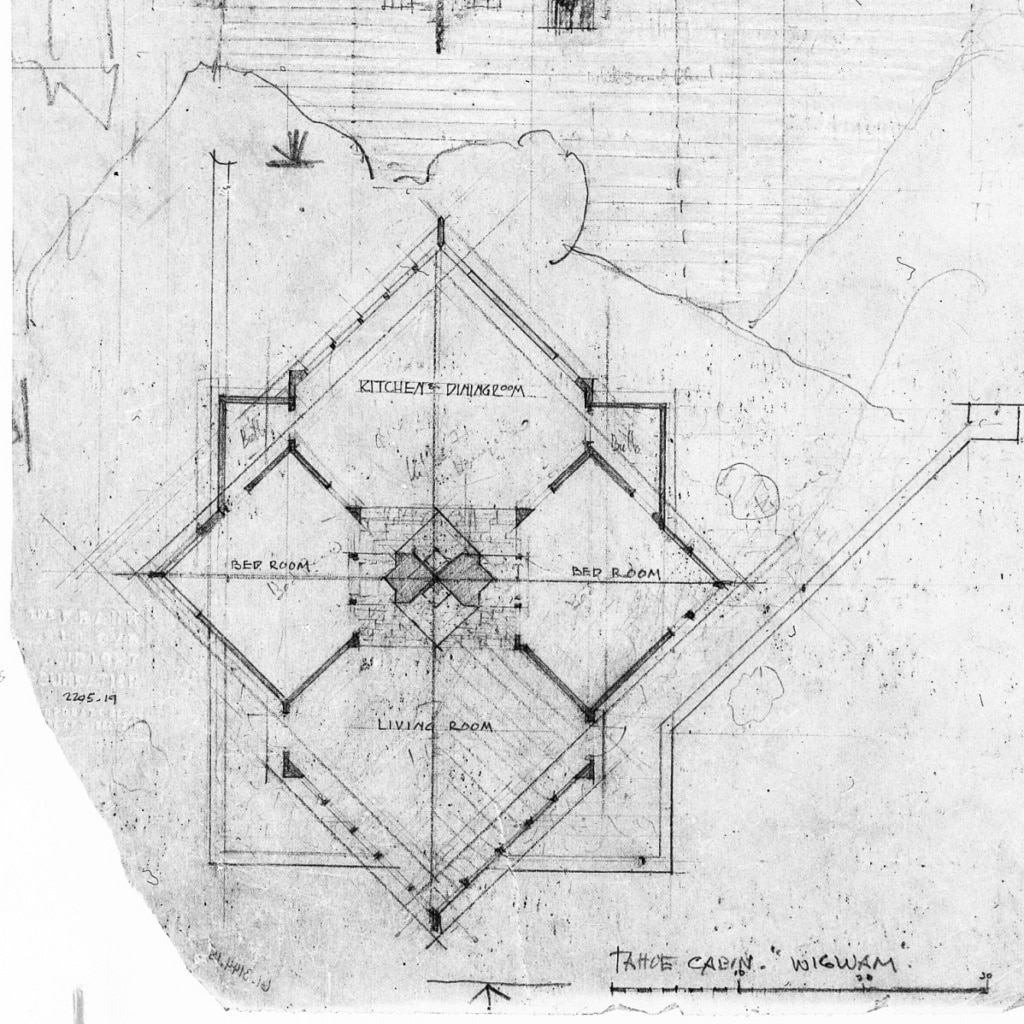

WIGWAM

archival plan

SHORE TYPE

archival plan

It is not known what drawings Wright might have brought with him on that visit. They may have included a series of cottages that he proposed: general prototypes that could be adapted to specific sites once work progressed. Finished perspectives for four survive; he called them Lodge, Shore, Fir Tree, and the dual-named Big Tree or Wigwam. They were to be located along the shore and on the lower slopes of the mountains, each with walls of stained boards, steep roofs of faceted copper, and retaining walls of concrete blocks to be made from white sand like that of the beach.

Wright’s perspective for the Lodge cottage depicts massively walled terraces that anchor the cottage firmly to its mountainous site. Projecting bays—some angled—enrich its building masses. In contrast, the extended plan of the Shore cottage relates to its placement along the narrow beach; the finished perspective shows cantilevered projections of an upper story, adding distinctive character. In the geometrically more complex Fir Tree cottage, wings extend out from a loosely octagonal core, terminating with angled bay windows that interlock with its terraced retaining walls. The more compact masonry base of the Big Tree or Wigwam cottage supports a symmetrical cluster of four rotated squares, their tips cantilevered over the walls below. The dual name Wright gave this cottage reflects both the tall trees of its setting and native American dwellings, the latter, for Wright, an example of indigenous architecture that provided a valid source for an American architecture. This cottage must have held special appeal for Jessie Armstrong; upon that first viewing of his drawings, she later said that Wright “had the plans for the Compoodi Indian type architecture for a home for mother and me on some site.” A rough sketch of a possible fifth prototype, with the cottage itself bridging a ravine, remained undeveloped.

FALLEN LEAF

rendering by David Romero

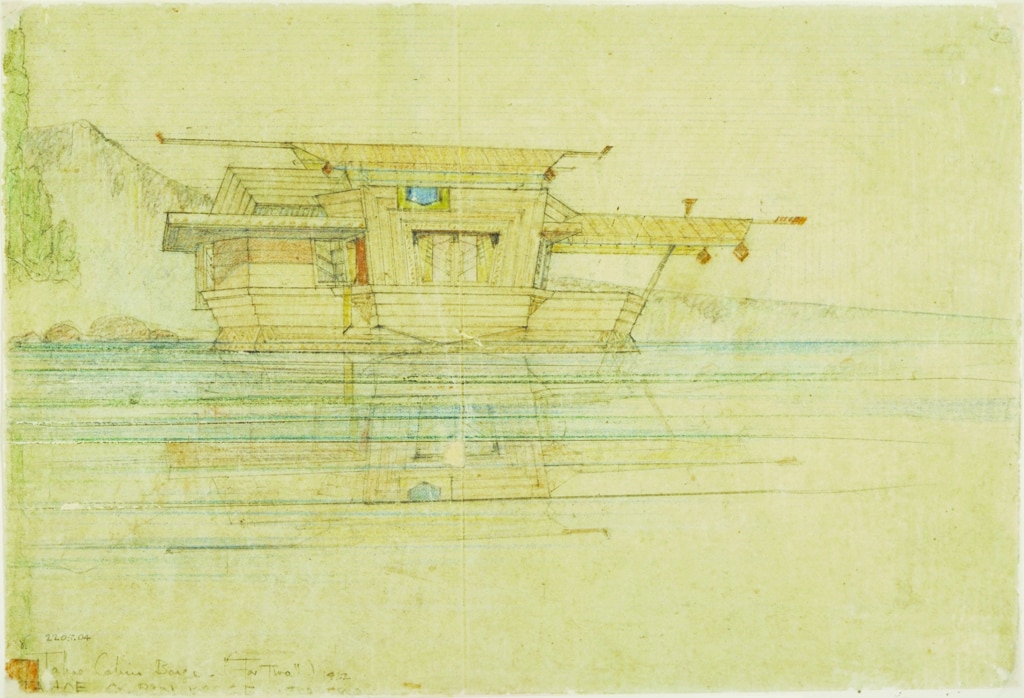

BARGE FOR TWO

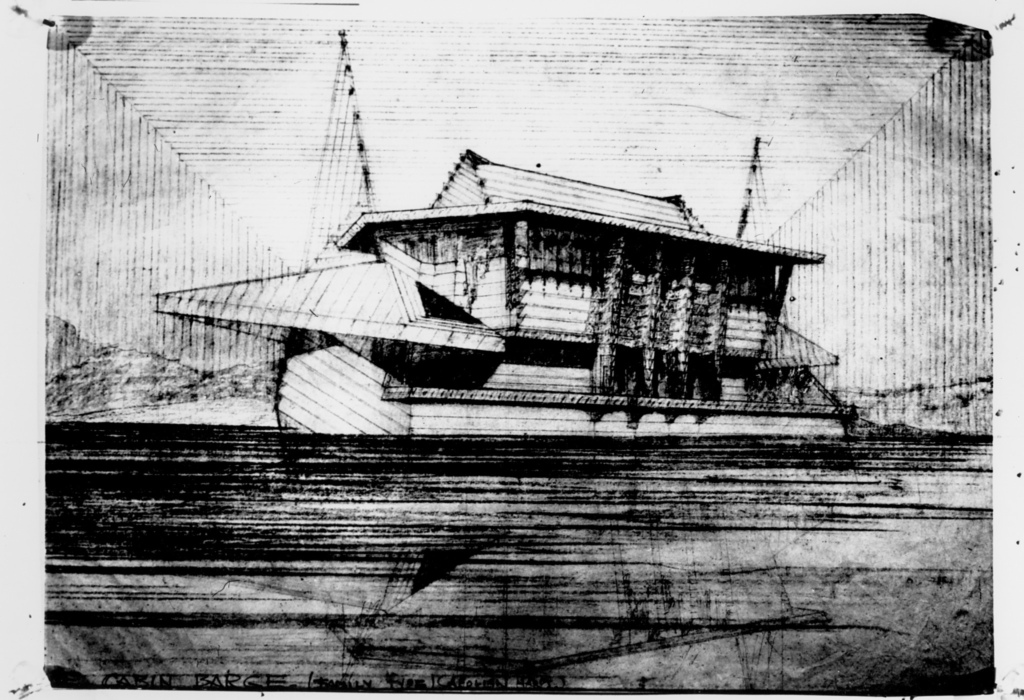

archival perspective

Wright also proposed an inn with pitched roofs and angled bays like those of Adirondack lodges. It was to be built over the bay itself, attached to the western side of the island and linked to shore by piers that extended nearly 1,000 feet. It would have felt appealingly isolated. Elsewhere on Lake Tahoe, even longer piers had been constructed, but Wright’s differed in being a network of piers supporting pavilions and enclosing water courts within their outlines, so they differed markedly from those earlier, simpler examples. A perspective drawn over an early photograph of Emerald Bay reflects his broadening attitude toward landscape.

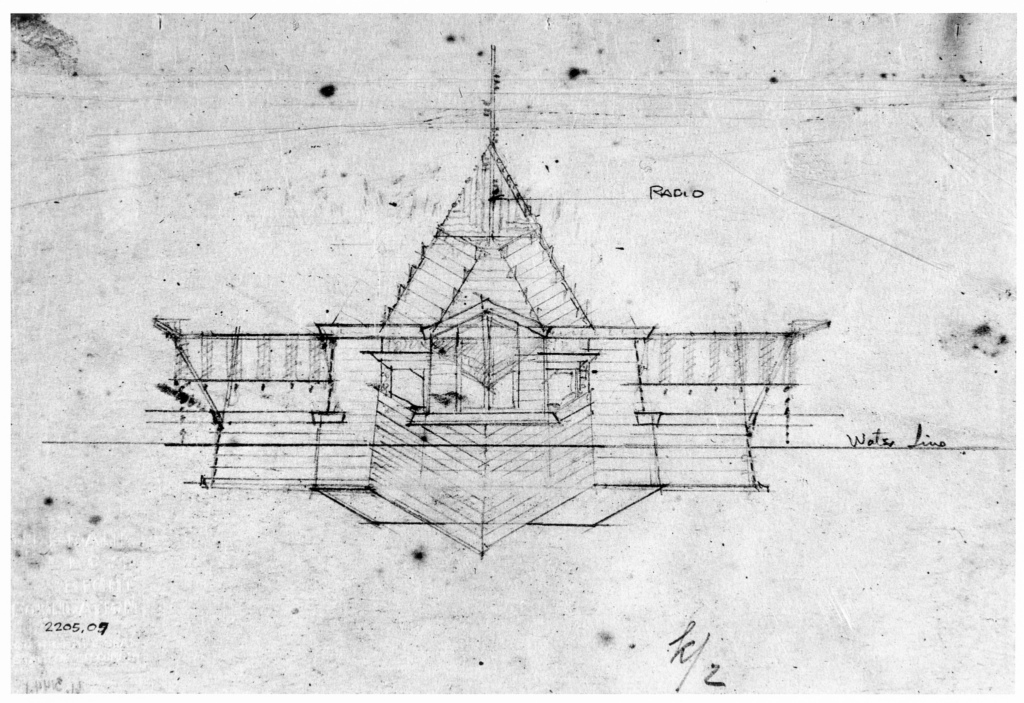

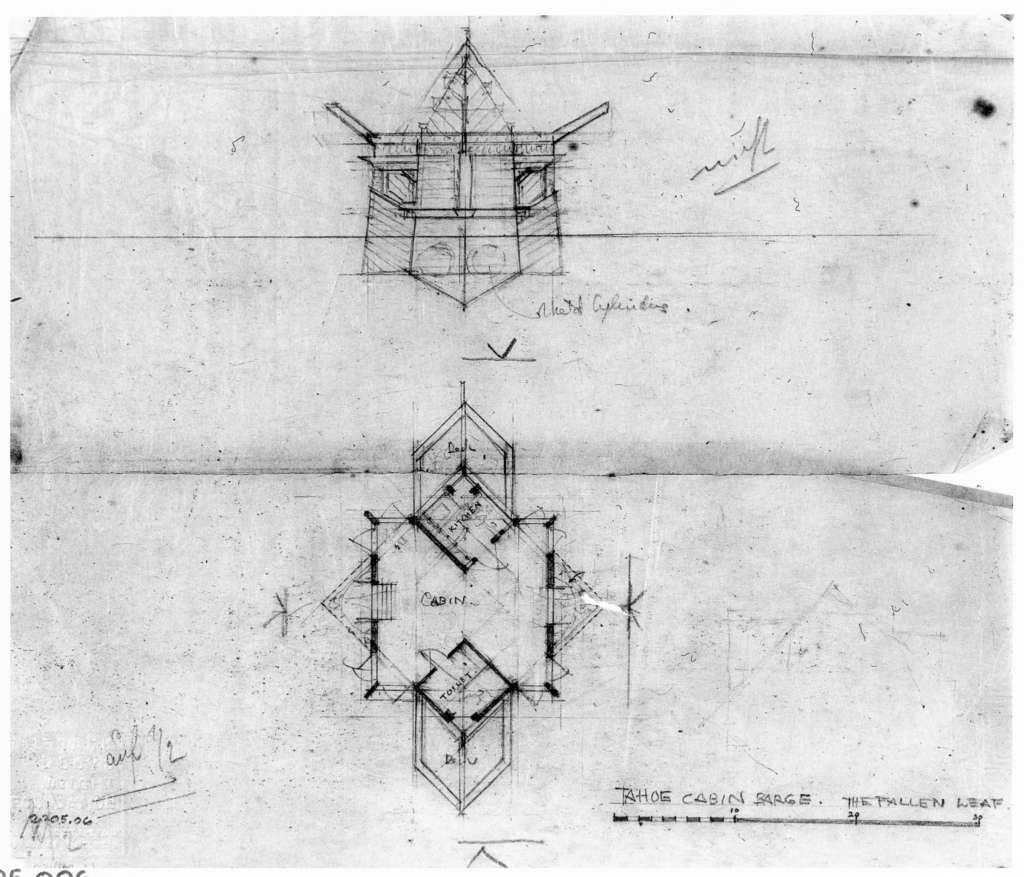

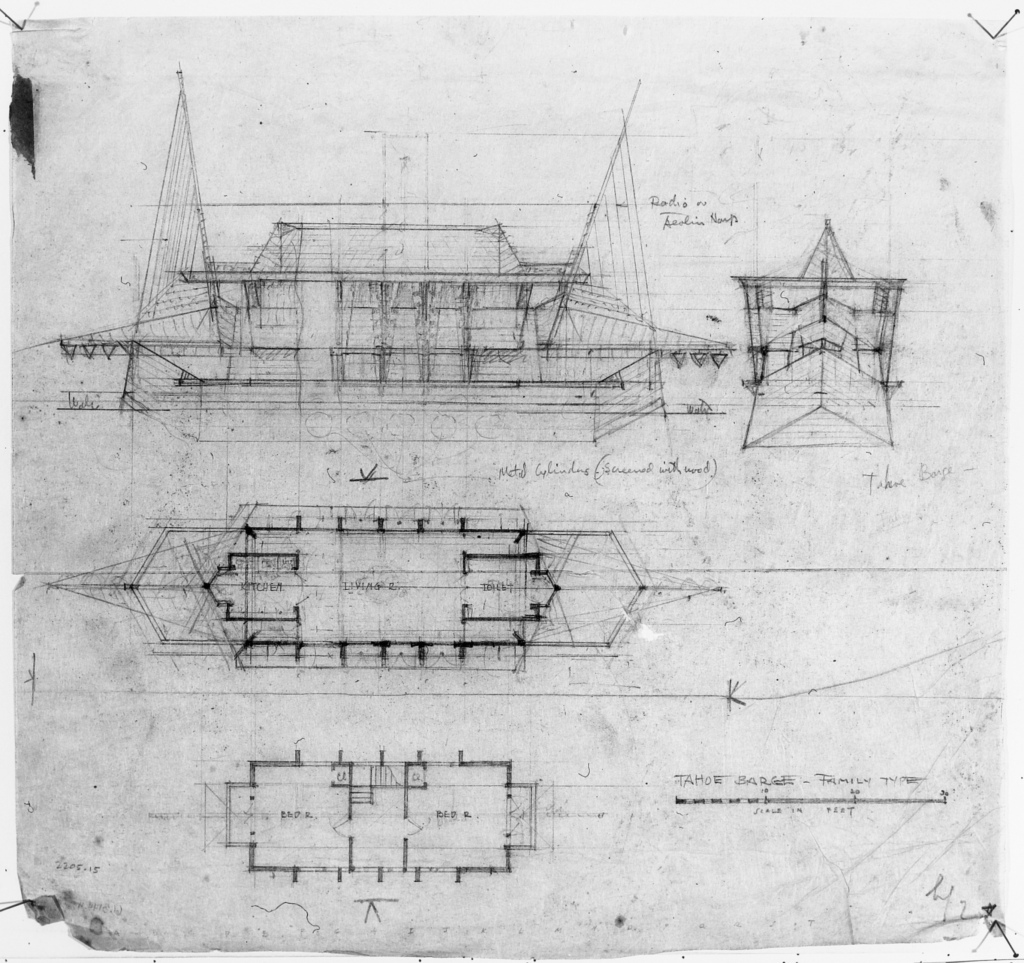

Plans for the inn show some 22 floating cabins that were to be moored along its piers, and as for the cottages, these were developed as a series of prototypes: Catamaran, Family, Fallen Leaf, and Barge for Two. They were like houseboats, but more sumptuously designed than most. The floating villa on Lake Nemi, built by the Roman emperor Caligula, offers a tantalizing precedent. Unlike Caligula’s, Wright’s floating cabins had no marble or elaborate baths, but instead echoed the vocabulary of the cottages, with faceted copper roofs and patterned board enclosures. Additional elements included extended masts and open, harp-like elements that Wright described as radio antennas; their open, diaphanous qualities would have resonated with the liquid transparency of the lake. As a group, the floating cabins constitute an architecture of mobility, with patterned surfaces that would have been amplified by their reflections in the rippling waters of the lake, as depicted by Wright in his finished renderings.

THE FALLEN LEAF

archival elevation

FAMILY TYPE

archival perspective

THE FALLEN LEAF

archival plan

FAMILY TYPE

archival plan

All of the floating cabins except the Catamaran had angled ends that would have facilitated their movement on the lake, and inclined sides would have added a boat-like appearance. To provide for long periods of sequestered leisure, Wright intended to position fixed-utility connections where the cabins could be moored for extended periods. All were two decks in height except for the single deck of the Fallen Leaf, which instead featured a steep, cone-like roof like that of the Fir Tree or Wigwam cottage. Of particular interest is the Barge for Two, which is apparently his first use of a fully hexagonal plan. Early designs by Wright had included hexagonal bays as adjuncts of more conventional spaces, but now that angularity infused the space in its entirety, shaping every room. Wright came to believe that such angularity was more responsive to human movement, and he exploited its potential to develop richly continuous volumes in later commissions. Among many notable examples, Auldbrass Plantation (near Yemassee, South Carolina), commissioned by Leigh Stevens in 1938 and mostly realized in the years that followed, shows how an expansive complex of interconnected structures could be effectively related through explorations of this modularity. A large guest house featuring a floating dining room on one side, detailed like the floating cabins of Lake Tahoe, was left unbuilt. Joel Silver, the current owner of Auldbrass who has restored the estate and its adjacent lake, intends to realize both the guest house and its floating room.

In the end, nothing came of Wright’s proposal for Lake Tahoe. Looking back, Jessie Armstrong said that “he had peculiar ideas of architecture; everyone didn’t respond to them.” She sold the land in 1928, and its next owner, Lara Josephine Moore Knight, built Vikingsholm on the site—a medievalizing confection quite different from what Wright had envisioned. Vikingsholm became part of a state park in 1953, and much of the Emerald Bay property remains undeveloped, making it easier to picture Wright’s unbuilt architecture of the lake itself.

DAVID G. DE LONG received his M.Arch degree at the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied with Louis I. Kahn, and his PhD. in architectural history at Columbia University, where he was associate professor of architecture. He returned to Penn as the inaugural chair of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation and is now professor emeritus of architecture at that university. He has published and lectured frequently on Wright and has curated exhibitions of Wright’s work. Among his books are Frank Lloyd Wright: Designs for an American Landscape, 1922–1932 (1996), Frank Lloyd Wright and the Living City (1998) and Auldbrass: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Southern Plantation (2011).