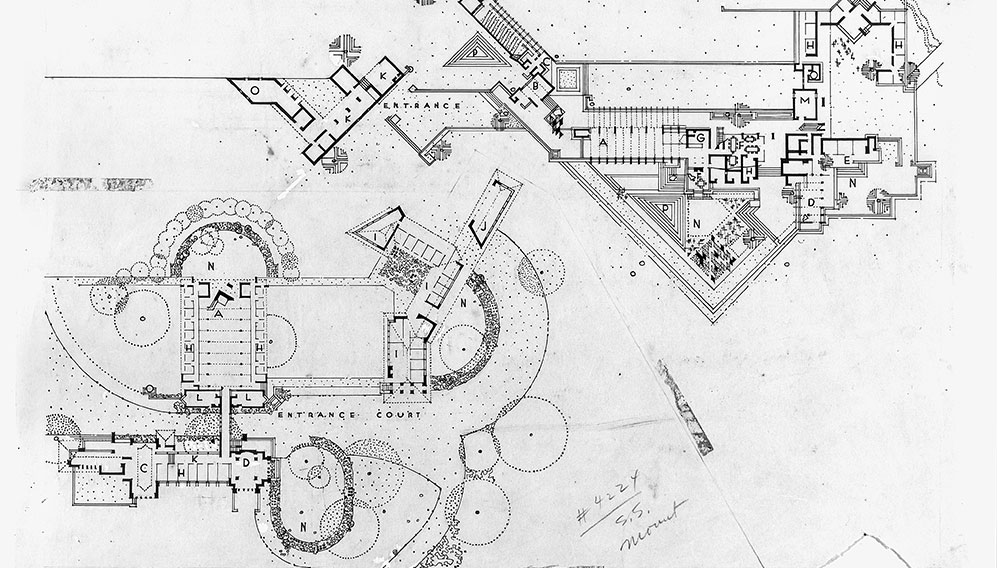

Frank Lloyd Wright changed the way we build and live

Wright came onto the scene at a time when the United States was struggling to define its architectural identity.

Most fashionable Americans still wanted their buildings—like themselves—dressed in European styles. To Wright, who believed that architecture was “the mother of all the arts,” this was unacceptable. Wright loved his country—its landscape, its people, its democratic ideals—and felt that the country desperately needed an architecture to reflect and celebrate its unique character: a truly American architecture. Wright would remain passionately devoted to this cause throughout his life.

Long before our modern emphasis on constant communication, Wright recognized that structure and space could themselves be powerful tools with which to create and convey cultural values. As such, he created dramatic new forms to promote his vision of America; a country of citizens harmoniously connected, both to one another and to the land. The primacy that his residential architecture gave to the hearth, the dining table, the music rooms, and the terrace, underscores this. His celebration of the human scale, his emphasis on creating a total environment, and the warmth that pervades all of Wright’s spaces, from the monumental to the miniscule, would warrant him a seat at any contemporary discussion panel on ‘placemaking.’ Furthermore, his approach to creating an architecture that appeared naturally linked to its surroundings, both in form and material, presaged many of today’s sustainability concerns. While American society may have changed markedly since the early 1900s, the underlying beliefs that Wright worked to uphold remain remarkably pertinent.

“We are all here to develop a life more beautiful, more concordant, more fully expressive of our own sense of pride and joy than ever before in the world.”

– Frank Lloyd Wright, 1957

Though values may be timeless, their vehicles must change. The passage of a century and the advent of minimalism and computer-calculated shapes have dimmed the radical edge of Wright’s work. This would not worry Wright; a man whose underlying thesis—that technology could and should be embraced as a powerful tool for a wide variety of creative and stylistic expression—has obvious parallels with contemporary explorations of digitally generated architectural forms. Wright embraced change, forever pushing the conceptual and technological frontiers of his field. Though he went to great lengths to make his buildings conform to his vision, he was not afraid to test his materials to the brink of failure. His continual over-reaching—with its sporadic structural shortcomings—reveals that, for Wright, the perfection of his buildings was secondary to their communication of an idea that would persist in “the mind’s eye of all the world.”

Photos: 1) Joe Koshollek 3) © 2017, Andrew Pielage

Like Wright, we find ourselves at a moment of technological development that will have significant effects on architectural form. We have the parallel sense that the world will never be the same. As with the machine age, the impact of the digital age will continue to be felt in architecture’s process, material, and appearance. Are we to use these technologies as simply a new set of tools with which to better achieve familiar forms, or are they the basis for an entirely new aesthetic? “As for the future—“ Wright prophesied, “the work shall grow more truly simple; more expressive with fewer lines, fewer forms; more articulate with less labor; more plastic; more fluent, although more coherent; more organic.” As we stride into a new millennium, and grapple with architecture’s responsibility to embrace the tools and embody the values of our time and place, we must acknowledge that in all of this, Wright walked before us.

Photo: © 2017, Andrew Pielage