The Life of Frank Lloyd Wright

“The mission of an architect is to help people understand how to make life more beautiful, the world a better one for living in, and to give reason, rhyme, and meaning to life.”

– Frank Lloyd Wright, 1957

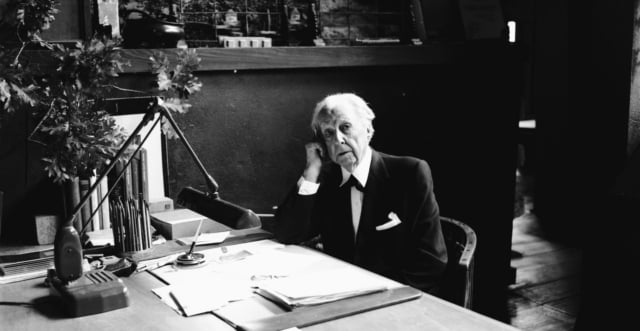

Ask the average citizen to name a famous American architect and you can bet that their answer will be Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright gained such cultural primacy for good reason: he changed the way we build and live. Designing 1,114 architectural works of all types — 532 of which were realized — he created some of the most innovative spaces in the United States. With a career that spanned seven decades before his death in 1959, Wright’s visionary work cemented his place as the American Institute of Architects’ “greatest American architect of all time.”

Early Life

The experiences of Wright’s upbringing were crucial in forming Wright’s unique aesthetic.

Frank Lloyd Wright was born in Richland Center, Wis., on June 8, 1867, the son of William Carey Wright, a preacher and a musician, and Anna Lloyd Jones, a teacher whose large Welsh family had settled the valley area near Spring Green, Wisconsin. His early childhood was nomadic as his father traveled from one ministry position to another in Rhode Island, Iowa, and Massachusetts, before settling in Madison, Wis., in 1878.

Wright’s parents divorced in 1885, making already challenging financial circumstances even more challenging. To help support the family, 18-year-old Frank Lloyd Wright worked for the dean of the University of Wisconsin’s department of engineering while also studying at the university. But, he knew he wanted to be an architect. In 1887, he left Madison for Chicago, where he found work with two different firms before being hired by the prestigious partnership of Adler and Sullivan, working directly under Louis Sullivan for six years.

Early Work

As Wright explored his personal interests, his work ushered in brand new styles of design.

In 1889, at age 22, Wright married Catherine Lee Tobin. Eager to build his own home, he negotiated a five-year contract with Sullivan in exchange for the loan of the necessary money. He purchased a wooded corner lot in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park and built his first house, a modest residence reminiscent of the East Coast shingle style with its prominent roof gable. It also reflected Wright’s ingenuity as he experimented with geometric shapes and volumes in the studio and playroom he later added for his ever-growing family of six children. Remembered by the children as a lively household, filled with beautiful things Wright found it hard to go without, it was not long before escalating expenses tempted him into accepting independent residential commissions. Although he did these on his own time, when Sullivan became aware of them in 1893, he charged Wright with breach of contract. It is not clear whether Wright quit or was fired, but his departure was acrimonious, creating a rift between the two men that was not repaired for nearly two decades. The split, however, presented the opportunity Wright needed to go out on his own. He opened an office and began his quest to design homes that he believed would truly belong on the American prairie.

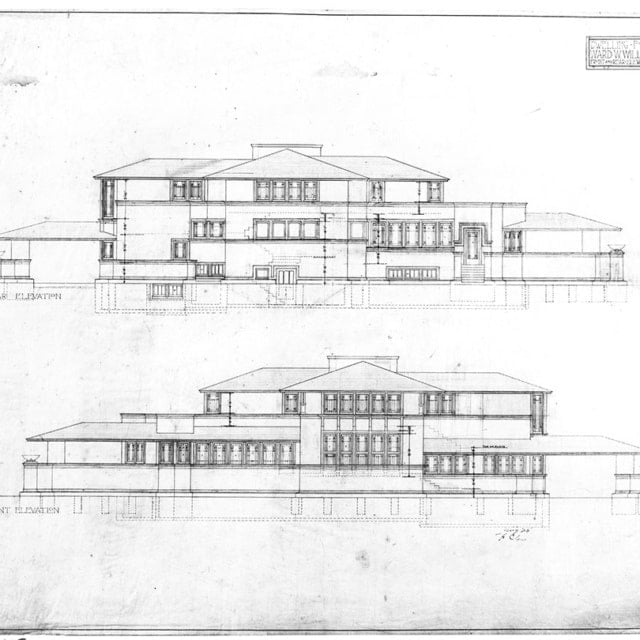

The William H. Winslow House was Wright’s first independent commission. While conservative in comparison to work of a few years later, with its broad sheltering roof and simple elegance, it nonetheless attracted local attention. Determined to create an indigenous American architecture, over the next sixteen years he set the standards for what became known as the Prairie Style. These houses reflected the long, low horizontal prairie on which they sat with low-pitched roofs, deep overhangs, no attics or basements, and generally long rows of casement windows that further emphasized the horizontal theme. Some of Wright’s most important residential works of the time are the Darwin D. Martin House in Buffalo, New York (1903), the Avery Coonley House in Riverside, Illinois (1907), and the Frederick C. Robie House in Chicago (1908). Important public commissions included the Larkin Company Administration Building in Buffalo (1903, demolished 1950) and Unity Temple in Oak Park (1905).

Creatively exhausted and emotionally restless, late in 1909 Wright left his family for an extended stay in Europe with Mamah Borthwick (Cheney), a client with whom he had been in love for several years. Wright hoped he could escape the weariness and discontent that now governed both his professional and domestic life. During this European hiatus Wright worked on two publications of his work, published by Ernst Wasmuth, one of drawings known as the Wasmuth Portfolio, Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright and one of photographs, Ausgeführte Bauten, both released in 1911. These publications brought international recognition to his work and greatly influenced other architects. The same year, Wright and Mamah returned to the States and, unwelcome in Chicago social circles, began construction of Taliesin near Spring Green as their home and refuge. There he also resumed his architectural practice and over the next several years received two important public commissions: the first in 1913 for an entertainment center called Midway Gardens in Chicago; the second, in 1916, for the new Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan.

In August 1914, Wright’s life with Mamah was tragically closed as she, her two children and four others were killed in a brutal attack and fire, intentionally started by an angry Taliesin domestic employee. Emotionally and spiritually devastated by the tragedy, Wright was able to find solace only in work and he began to rebuild Taliesin in Mamah’s memory. Once completed, he then effectively abandoned it for nearly a decade as he pursued major work in Tokyo with the Imperial Hotel, which was demolished 1968, and Los Angeles with the Hollyhock House and Olive Hill for oil heiress Aline Barnsdall.

Photos: 2) Nick Abele

Learn More: Explore Frank Lloyd Wright’s Work

Taliesin Fellowship

Wright sought to teach others by having them become active in each aspect of his projects

The years between 1922 and 1934 were both architecturally creative and fiscally catastrophic. Wright had established an office in Los Angeles, but following his return from Japan in 1922 commissions were scarce, with the exception of the four textile block houses of 1923–1924 (Millard, Storer, Freeman and Ennis). He soon abandoned the West Coast and returned to Taliesin. While only a few projects went into construction, this decade was one of great design innovation for Wright. Among the unbuilt commissions were the National Life Insurance Building (Chicago, 1924), the Gordon Strong Automobile Objective (Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland, 1925), San Marcos-in-the-Desert resort (Chandler, Arizona, 1928), and St. Mark’s-in-the-Bowerie apartment towers (New York City, 1928).

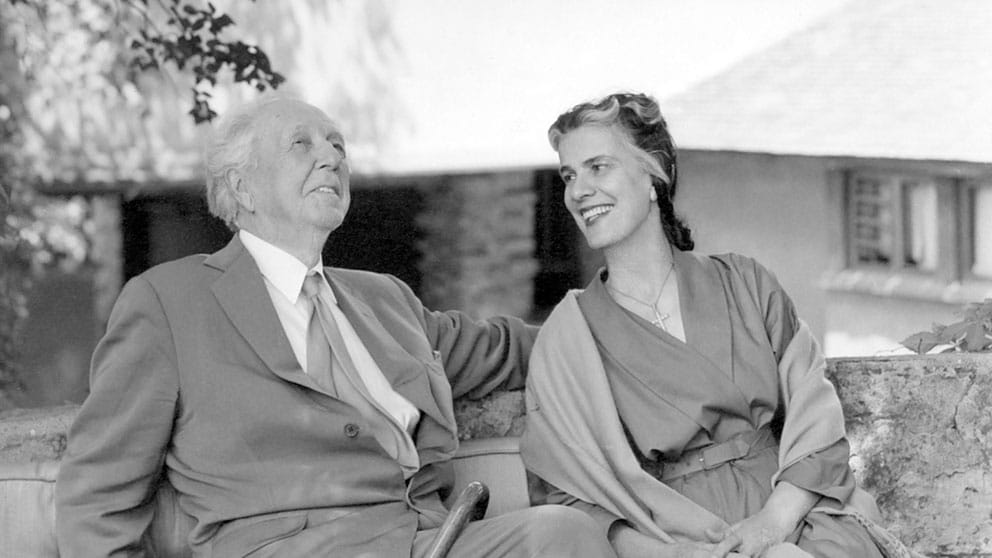

In 1928, Wright married Olga Lazovich (known as Olgivanna), daughter of a Chief Justice of Montenegro, whom he had met a few years earlier in Chicago. She proved to be the partner and stabilizing influence he needed in order to refocus on “the cause of architecture” he had begun decades earlier.

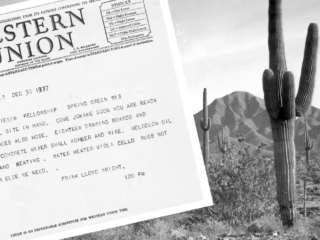

With few architectural commissions coming his way, Wright turned to writing and lecturing which introduced him to a larger national audience. Two important publications came out in 1932: An Autobiography and The Disappearing City. The first received widespread critical acclaim and would continue to inspire generations of young architects. The second introduced Wright’s scheme for Broadacre City, a utopian vision for decentralization that moved the city into the country. Although it received little serious consideration at the time, it would influence community development in unforeseen ways in the decades to come. At about this same time, Wright and Olgivanna founded an architectural school at Taliesin, the “Taliesin Fellowship,” an apprenticeship program to provide a total learning environment, integrating not only architecture and construction, but also farming, gardening, and cooking, and the study of nature, music, art, and dance.

Later Life

For Wright, creation continued until the very end

Remarkable Return

With this larger community to take care of, and Wisconsin winters brutal, the winter of 1934 found the Wrights and the Fellowship in rented quarters in the warmer air of Arizona where they worked on the Broadacre City model, which would debut in Rockefeller Center in 1935. Wright was by this time still considered a great architect, but one whose time had come and gone. In 1936, Wright proved this sentiment wrong as he staged a remarkable comeback with several important commissions including the S.C. Johnson and Son Company Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin; Fallingwater, the country house for Edgar Kaufmann in rural Pennsylvania; and the Herbert Jacobs House (the first executed “Usonian” house) in Madison.

At this same time, Wright decided he wanted a more permanent winter residence in Arizona, and he acquired some acreage of raw, rugged desert in the foothills of the McDowell Mountains in Scottsdale. Here he and the Taliesin Fellowship began the construction of Taliesin West as a winter camp, a bold new endeavor for desert living where he tested design innovations, structural ideas, and building details that responded to the dramatic desert setting. Wright and the fellowship established migration patterns between Wisconsin and Arizona.

Acknowledging Wright’s stunning reentry into the architectural spotlight, the Museum of Modern Art in New York staged a comprehensive retrospective exhibition that opened in 1940. In June 1943, undeterred by a world at war, Wright received a letter that initiated the most important, and most challenging, commission of his late career. Baroness Hilla von Rebay wrote asking him to design a building to house the Solomon R. Guggenheim collection of non-objective paintings. Wright responded enthusiastically, never anticipating the tremendous amount of time and energy this project would consume before its completion sixteen years later.

The Last Decades

With the end of the war in 1945, many apprentices returned and work again flowed into the studio. Completed public projects over the next decade included the Research Tower for the SC Johnson Company, a Unitarian meeting house in Madison, a skyscraper in Oklahoma, and several buildings for Florida Southern College. Other, ultimately unbuilt, projects included a hotel for Dallas, Texas, two large civic commissions for Pittsburgh, a sports club for Hollywood, a mile-high tower for Chicago, a department store for Ahmedabad, India, and a plan for Greater Baghdad.

Wright opened his last decade with work on a large exhibition, Frank Lloyd Wright: Sixty Years of Living Architecture, which was soon on an international tour traveling to Florence, Paris, Zurich, Munich, Rotterdam, and Mexico City, before returning to the United States for additional venues. Impressively energetic for man in his eighties, he continued to travel extensively, lecture widely, and write prolifically. He was still actively involved with all aspects of work including frequent trips to New York to oversee construction of the Guggenheim Museum when, in April of 1959, he was suddenly stricken by an illness which forced his hospitalization. He died April 9, two months shy of his ninety-second birthday.

Style & Design

Wright’s style and design changed as he responded to the needs of American society

Prairie Style

Wright’s work from 1899 to 1910 belongs to what became known as the “Prairie Style.” With the “Prairie house”— a long, low, open plan structure that eschewed the typical high, straight-sided box in order to emphasize the horizontal line of the prairie and domesticity— Wright established the first truly American architecture. In a Prairie house, “the essential nature of the box could be eliminated,” Wright explained. Interior walls were minimized to emphasize openness and community. “The relationship of inhabitants to the outside became more intimate; landscape and building became one, more harmonious; and instead of a separate thing set up independently of landscape and site, the building with landscape and site became inevitably one.”

Photo: Dianne Plunkett Latham

Usonian

Responding to the financial crisis of 1929 and ensuing Great Depression that gripped the United States and the rest of the world, Wright began working on affordable housing, which developed into the Usonian house. Wright’s Usonians were a simplified approach to residential construction that reflected both economic realities and changing social trends. In the Usonian houses, Wright was offering a simplified, but beautiful environment for living that Americans could both afford and enjoy. Wright would continue to design Usonian houses for the rest of career, with variations reflecting the diverse client budgets.

Philosophy

Design for Democracy

Wright always aspired to provide his client with environments that were not only functional but also “eloquent and humane.” Perhaps uniquely among the great architects, Wright pursued an architecture for everyman rather than every man for one architecture through the careful use of standardization to achieve accessible tailoring options to for his clients.

Integrity and Connection

Believing that architecture could be genuinely transformative, Wright devoted his life to creating a total aesthetic that would enhance society’s well being. “Above all integrity,” he would say: “buildings like people must first be sincere, must be true.” Architecture was not just about buildings, but about nourishing the lives of those within them.

“There is no architecture without a philosophy. There is no art of any kind without its own philosophy.”

– Frank Lloyd Wright, 1959

Nature’s Principles and Structures

For Wright, a truly organic building developed from within outwards and was thus in harmony with its time, place, and inhabitants. “In organic architecture then, it is quite impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and its setting and environment still another,” he concluded. “The spirit in which these buildings are conceived sees all these together at work as one thing.” To that end, Wright designed furniture, rugs, fabrics, art glass, lighting, dinnerware, and graphic arts.

Material and Machine

Wright embraced new technologies and tactics, constantly pushing the boundaries of his field. His fascination for the new and his desire to be a pioneer help explain Wright’s tendency to test his materials—sometimes even to the brink of failure—in an effort to achieve effects he could claim as uniquely his own.

Architecture as the Great Mother Art

Wright devoted his life to promoting architecture as “the great mother art, behind which all others are definitely, distinctly and inevitably related.” Seeking a consistent expression of underlying unity, he drew inspiration from the Japanese idea of a culture in which every object, every human, and every action were integrated so as to make an entire civilization a work of art. Above all else, Wright’s vision served beauty. He believed that every man, woman and child had the right to live a beautiful life in beautiful circumstances and he sought to create an affordable architecture that served that aspiration.

Photos: 1) © Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. 3) Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

Writings

Fundamental to understanding Wright’s work, his writings allow readers to see into his creative mind through an intimate lens.

Wright’s own texts are a testament to the fact that his ability to articulate himself matched his genius with brick, concrete and glass. His books offer readers an exclusive glimpse into the life and work of the complex architect.