The Muse of Music: Wright’s Legacy in Song

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation | Jul 17, 2022

In the Spring 2022 Quarterly, Graphic Design Fellow Brie Flewelling explores the impact of music on Frank Lloyd Wright, and in turn the effect of Wright’s work and legacy on contemporary musicians.

At the turn of the 19th century, Ludwig van Beethoven was in need of a good architect. Infamously tempestuous and fussy, the composer moved more than 65 times in the 35 years he spent in Vienna after spurring complaints from neighbors or quarreling with landlords. Finding a suitable venue for his performances was a constant struggle as well. At the time, public concerts were exceedingly uncommon, and there were no dedicated show spaces for music, creating demand for theaters and other large, rentable rooms that booked quickly.

Less than a century later, a young Frank Lloyd Wright would listen to his father play bars of Beethoven late into the night. Wright would later state in An Autobiography, “When I build, I often hear his [Beethoven’s] music and, yes, when Beethoven made music I am sure he sometimes saw buildings like mine in character, whatever form they may have taken then.” Suppose that beyond the inadequate apartments and the desperation for a decent venue for his performances, Beethoven longed for a new kind of space, a structure suitable for his late-night piano playing and for a large audience to appreciate his work. Perhaps this can be attributed to the architectural restlessness of Beethoven, his propensity towards a nomadic, trailing existence evident in everything he did, from his many apartments to his wild handwriting, his notes wandering far from the musical staff.

Frank Lloyd Wright playing the piano in 1955 at Taliesin during a photo shoot.

Wright was not one to credit inspiration lightly, yet spoke often of the impact Beethoven, Bach, Brahms and other musical greats had on him and his work. In one conversation about the Coonley house, he stated, “Articulate buildings of this type have their parallel in the music of Bach particularly, but in any of the true form-masters in music.” Synesthetic comments like this are common in Wright’s prose and interviews. Apprentice John Lautner once recounted a story of Wright comparing his work to Beethoven, “‘…he said, ‘with these 16 foot centers,’ [Lautner gestures at beams in the Garden Room at Taliesin West]…he said, ‘you can hear the module in the Beethoven music.’”

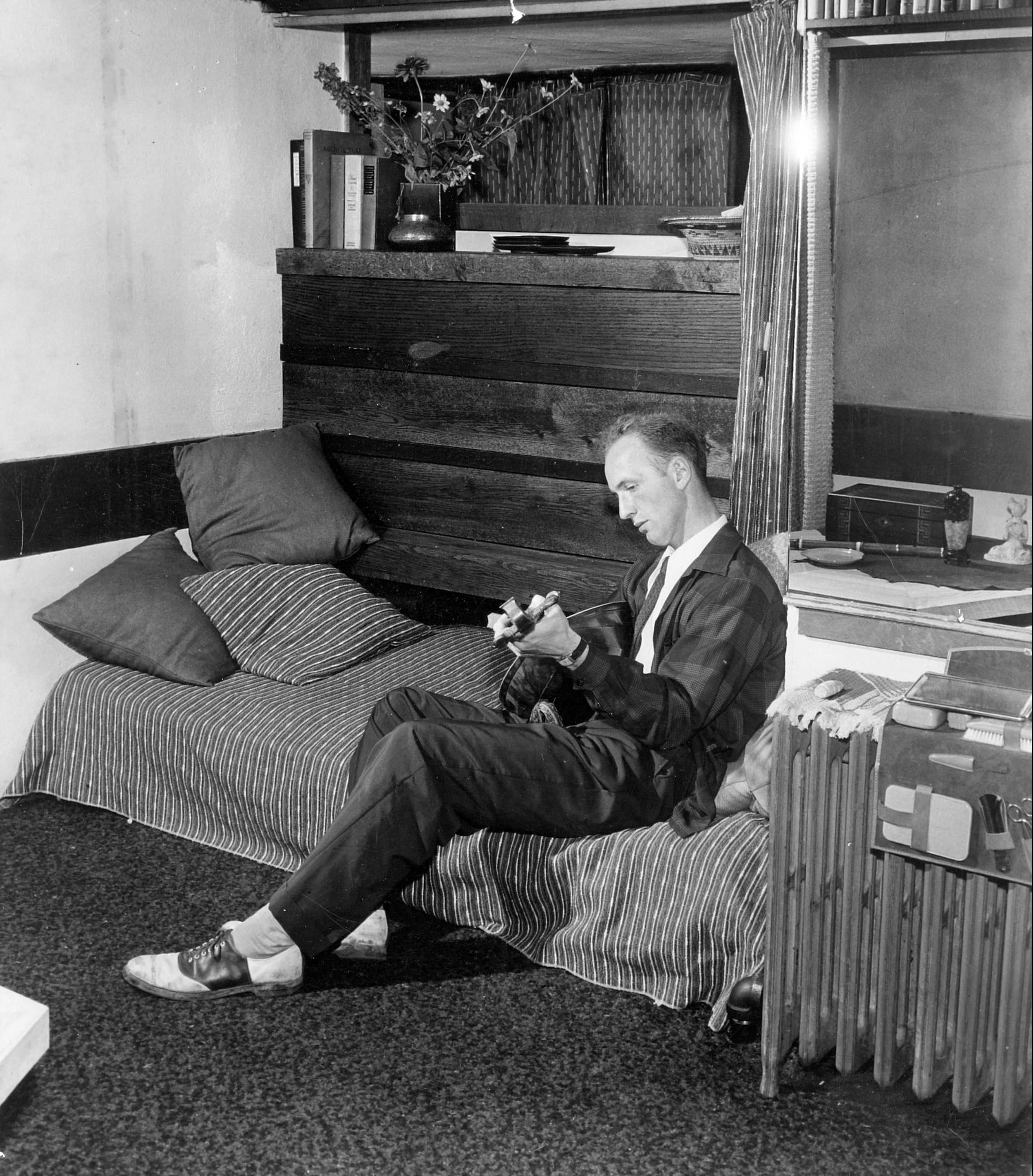

Apprentice John Hill in Hillside Corridor room, perhaps playing a mandolin.

The connection between Wright and music is a strong one, beginning in his most formative years. His father, William Russell Cary Wright, was a musician and composer. Reminiscing on his father’s performances, he once wrote, “To my young mind it all spoke a language that stirred me strangely, and I’ve since learned it was the language beyond all words, of the human heart. To me, architecture is just as much an affair of the human heart,” Wright ensured that music was a key component of the Fellowship, an essential part of his students’ educations. Included as an area of interest on the application form, many of the apprentices learned to play an instrument and participated in performances. When Wright settled on a location for Taliesin West, his winter home in Scottsdale, Arizona, he wrote to his secretary to bring various tools, drafting supplies, and violins. All were necessities to build the desert outpost. To this day, multiple pianos grace the property, testaments to the musical origins of the space.

Wright, though certainly a visionary, was not unique in relating architecture to music. Architects as historically distant as Vitruvius, or as current as Daniel Libeskind, have connected their work to the artform. Creatives have spent eons examining the likenesses of music and architecture, and even today we turn through the annals of history, holding up the artforms to examine them in fresh light and context. Both are structurally similar, requiring balanced doses of arrangement and texture. The materials of architecture are equivalent to the instruments of a symphony, each an element in service of a larger whole.

Claude Debussy once described music as “the space between the notes,” an eloquent reminder that music is only audible for its lacking. Both music and architecture require a kind of harmony, rhythm created in a playground of place and space, solid and void, chiaro and scuro. Wright once observed,“It seems to me that music is a kind of sublimated mathematics. So is architecture … There lies the great relationship and warm kinship between music and architecture. They require very much the same mind.”

The music of Bach overlaying Marin County Civic Center. Collage by Brie Flewelling, photo by Mark Hertzberg.

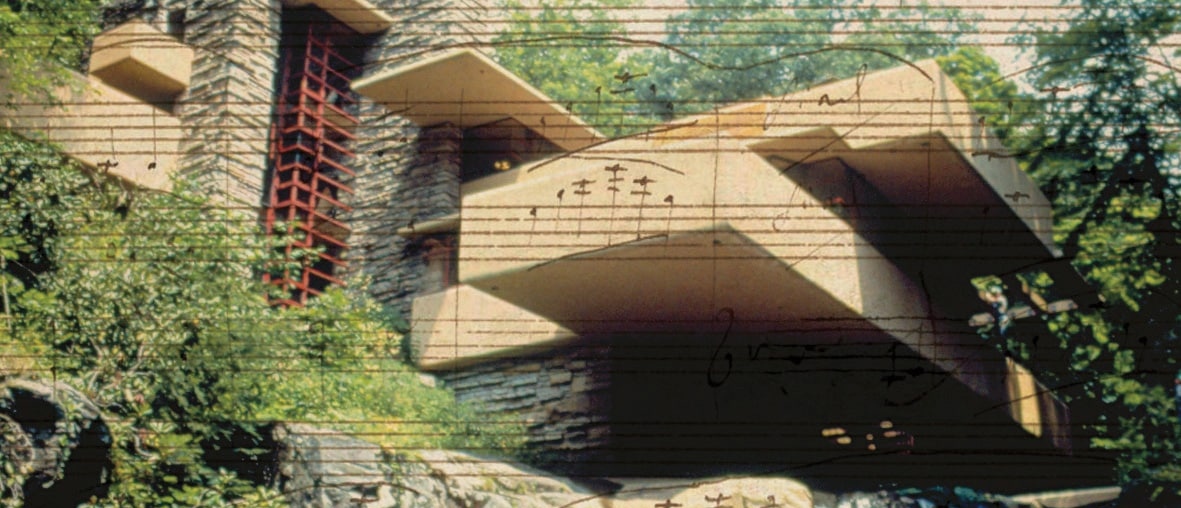

Imagine Wright’s work through this lens, these buildings built to the tune of Beethoven and Bach, Mozart, and Brahms: In the drafting studio of Taliesin West, the earthy red beams become the sound, the tan canvas between them the silence. At Fallingwater, the stacked sandstone verticals are the notes, the concrete cantilevers, the interval. At the Guggenheim Museum, the ramp wraps the space like a music staff , punctuated by colorful art, the staccato in an otherwise white-grey silence.

Music and architecture represent sensory arenas, extending far beyond mere auditory or visual realms. Music can do far more than fill our ears, the experience sometimes deepening into touch and emotion. It can trail its icy fingers along our arms leaving goosebumps in its wake or can overwhelm with joy or sorrow. Wright used the design principle of ‘compression and release’ in his work to similarly influence feeling and psychology. His entrances are often low-ceilinged and small, giving way to a vaulted room, inducing in visitors a subconscious held breath as they enter the space. Windows are situated in such a way to expose carefully curated views only once a person has sunk into a chair lateral to the glass, extending the initial sense of discovery of the space itself into the world beyond as they interact with the architecture. In the performance spaces he designed he honed the auditory experience by adjusting the form to amplify sound from the stage into the audience. The words of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the German polymath, succinctly summarized the relationship between the two artforms, “Music is liquid architecture; Architecture frozen music.”

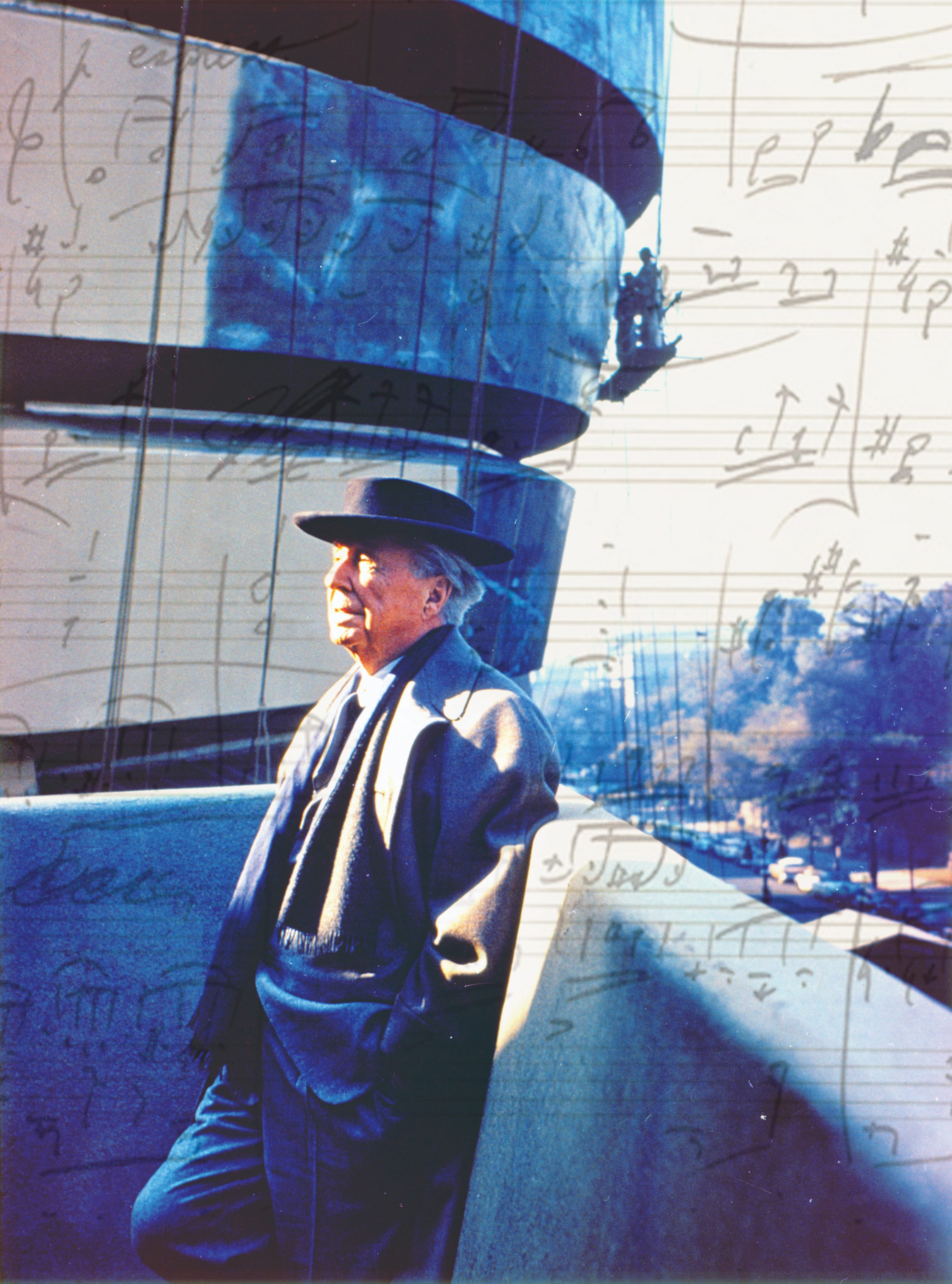

Of course, the relationship between these arts and inspiration is symbiotic. Just as Wright was inspired by music, musicians today are similarly inspired by Wright and his architecture. While his buildings may be firmly planted in their grounds, the legacy of his work is ever-moving, found in places as obvious as archives and architecture studios, or as unexpected as a car radio playing “So Long, Frank Lloyd Wright” by Simon and Garfunkel.

This is far from the only song written about Wright and his oeuvre. In March of 2020, Phoebe Bridgers, a 25-year-old alternative musician, sat down in front of an Instagram Live stream, and began to strum and sing. “On that Shining Brow of Taliesin, someone might try and burn it down, so you’ll have to put the fi re out, a fortune spent but that’s irrelevant to build something that’s sacred to the end.”

The performance was a cover of a song entitled, “Mamah Borthwick (a sketch),” and was originally written and performed by Conor Oberst, the frontman of Bright Eyes. The lyrics ruminate on what it takes to create a legacy, embellishing the story with Wright’s enduring structures.

Music by Palestrina overlays a photo of Wright at the Guggenheim Museum in 1959. Collage by Brie Flewelling.

Mentions and references to Wright and his work span musical generations and genres. Pop duo The Ting Tings sing out, “I’m gonna paint my face like the Guggenheim!” Indie-Alternative singer Maggie Rogers soulfully belts, “And now I’m in the creek, and it’s getting harder, I’m like Fallingwater,” in a song named for the iconic house. Contemporary composer Christopher Slaski created “The Frank Lloyd Wright Suite.”

Each of the four movements, recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra, were named for works by Wright: “Wingspread,” “Fallingwater,” “Solar Hemicycle,” and “Guggenheim NYC.” On Spotify, a popular music-sharing platform, two songs are entitled “Taliesin West:” one a rap, the other low-fi and instrumental. Some music groups have used the architect’s name as a jumping off point for their band names. From “Frank Lloyd Wrong” to “Frank Lloyd Riot,” the references are often arbitrary and tongue-in-cheek, having only the barest of ties to the architect himself. They act more as a testament to the tendrils of legacy—its wide-set roots that disappear as they travel, then suddenly break through the ground again in entirely new decades and disciplines.

Wright once said, “Never miss the idea that architecture and music belong together. They are practically one.” Next time you visit a Frank Lloyd Wright site, take a moment to listen. Perhaps you’ll hear the shuffle of feet on concrete or wood, the quiet whir of hidden mechanicals, or the symphony of the outside world drifting through single pane glass. If you listen hard enough, you may even catch a few bars of Beethoven drifting down from the rafters.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. The Quarterly magazine is a member-exclusive benefit. To receive current and future issues, become a member today.

Click here for more information and to see past issues of the Quarterly.

BRIE FLEWELLING is the 2021–2022 Graphic Design Fellow at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Creative Director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly magazine. Music is an essential part of her work, and she can be often found working at her desk with a set of headphones on. This article was written to the sounds of Hozier, Maggie Rogers, Slow Meadows, and Hania Rani.