A Curator’s Reflection on Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive

Barry Bergdoll | Aug 16, 2017

Barry Bergdoll, curator of the Museum of Modern Art’s “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” explains the journey of unpacking the multifaceted career of America’s greatest architect and presenting it in an exciting and forward-looking way.

There was a great deal of nervousness on all sides five years ago as the three-party agreement on the transfer of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation archives from Scottsdale and Spring Green was signed between the Foundation, the Avery Fine Arts and Architectural Library at Columbia University, and The Museum of Modern Art after many, many months of discussions and fine-tuning. For the Foundation, the transfer meant entrusting a very important part of the heritage of Frank Lloyd Wright that had been carefully held, catalogued, and studied for many decades — notably under the leadership of the tireless Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer and in more recent years Margo Stipe — into new hands some two thousand miles away. It was an emotional moment, even if many had come to terms intellectually with the argument that the transfer to a more readily accessible repository, with a broader audience and professional resources in place, made a great deal of sense in conservation and scholarship terms. The archive was, after the buildings, furniture, and landscape of the two Taliesins, the most tangible link to Wright and the early years of the Taliesin Fellowship.

At Columbia, for Janet Parks, Carol Ann Fabian, and the whole staff of the Avery Library, it meant a daunting logistical task first of housing a huge archive in already densely configured archival storage at the heart of the Morningside Heights campus, even as it promised a huge increase in the number of researchers and research requests of materials at the nation’s largest architecture library. For MoMA, it meant a conservation task as some of the architectural models, notably, were in crying need for restoration and professional storage. But equally, it meant the commitment not only to exhibit the materials regularly, but to mark the joint anniversaries of Wright’s 150th birthday and the fifth birthday of the archive’s new home with a major exhibition. This task fell to me, and made me wonder if I was not the most nervous of all. Nervous because although I have known Wright as a professor of modern architectural history and a curator, I am by no means a Frank Lloyd Wright scholar (although I am fast becoming one by osmosis!)

I don’t know at what point in my panic of how to approach an exhibition to occupy 10,000 square feet of newly reconfigured galleries at MoMA — and thus one of the largest exhibitions in the eighty-five year history of the Architecture Department at MoMA — gave rise to the concept of “Unpacking the Archive.” It certainly seemed — in the wake of such recent comprehensive exercises as Neil Levine’s magisterial Frank Lloyd Wright of 1997 and the retrospective that filled the ramp of the Guggenheim Museum of 2009 — that it would be hard for a newcomer to Wright studies to advance single-handedly an interesting and relevant take on the shape or meaning of Wright’s seven decades of design practice. A solution to this dilemma of staging something more meaningful than a show of masterworks from the Wright archive came with the realization of the obvious: namely that the show was to underscore precisely what we had promised through the long period of courtship with the Foundation and the claims that we continued to reiterate. The underlying commitment of the unusual university library/museum partnership as stewards of the archive was to open new horizons for Wright scholarship and public understanding in tandem. Over and over again we had reiterated that the new institutional framework for the drawings, letters, photographs, models, building fragments, etc., of the Foundation archives would be to reinvigorate study and thinking on Wright, and to open him up both to new historical questions and to new connections with those aspects of his work which resonate with evolving 21st century concerns. Clearly, then, the exhibition had to be as much about scholarship in the archive, as about Wright as architect. In other words, the archive would not disappear when put on display in the museum, but the exhibition would be an exhibition of an extraordinary archive.

Left and above: Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. Photos by Jonathan Muzikar.

Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar.

The idea then was born to invite a group of scholars with interesting perspectives on the history of late 19th and 20th century architecture to work on an aspect of Wright from a fresh point of view. While it would have been easy to invite the established Wright scholars to guest curate a section of an exhibition to be organized as an anthology, this would have served only to communicate that only those with established credentials – and indeed many of the leading Wright scholars have multiple hefty volumes to their name – were in a position to open up the archive to new insights. In the end, only two of the many possible Wright experts, Neil Levine and Michael Desmond, were to take part in the final display, although advice came from many others, including Anthony Alofsin and Joseph Siry.

It was risky to turn to people with no established track record in studying Wright and, for the most part, with no experience of developing their ideas through the medium of exhibition, as opposed to written word accompanied by illustrations. But looking back now, after two years of developing and leading this concept that brought together thirteen historians and a museum conservator, it seems to me that the goal was achieved. The announcement has been made that the Wright archive is here in New York, accessible to scholars, even those who don’t intend to write a major book on Wright. The process of reintegrating Wright scholarship in the larger debate on architecture and architecture history has thus been much advanced.

By now, from the considerable press coverage, the concept is known even to many Wright enthusiasts who have not been able to view the display or read the catalogue. Each invited “unpacker” was asked to select a single objet – drawing, model, photograph – in the archive that intrigued them and to develop a check list of materials that could help interpret that work as a window into Wright’s multi-faceted and lengthy career. Like Walter Benjamin who rediscovered his library in the process of moving it (“Unpacking my Library” 1931), each of the “unpackers” sheds new light on an aspect of Wright by selecting materials from the archive and placing them into juxtaposition with one another and with works from other repositories to offer a history and interpretation of an aspect of Wright’s work.

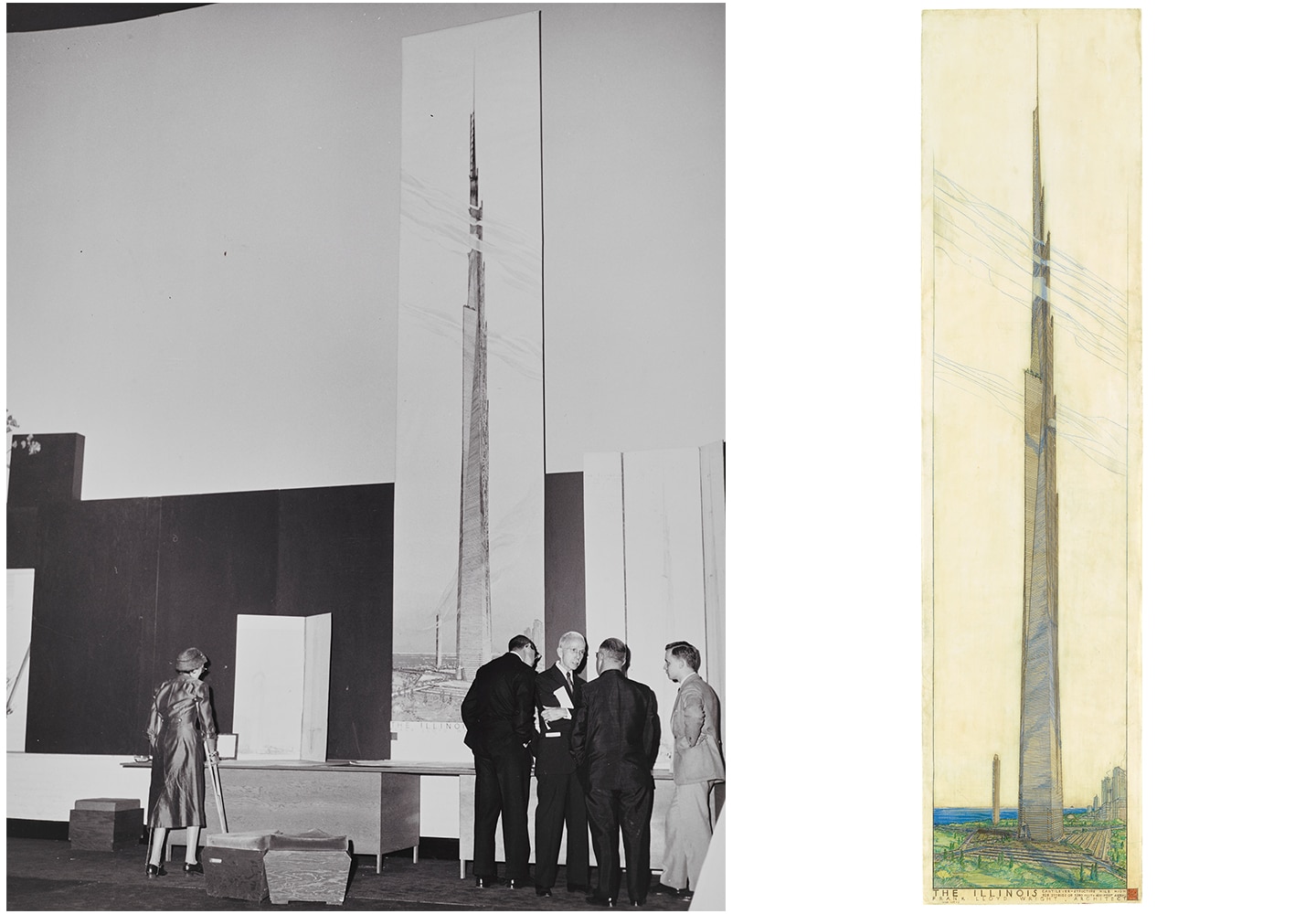

I choose, for instance, one of the most puzzling drawings for Wright’s outlandish project for a Mile High Skyscraper of 1956 in which the entire upper half of the drawing, more than eight feet tall, is taken up with a lengthy scroll of inscriptions and the largest of all Wright’s designs for a tap root tower anchors itself in the earth amidst a panorama of record-breaking buildings from the millennia.

Left: Unveiling the 22-foot-high (6.7-meter-high) visualization of The Mile-High Illinois at the October 16, 1956, press conference in Chicago. Right: Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). The Mile-High Illinois, Chicago. Project, 1956. Perspective with the Golden Beacon Apartment Building project (1956–57). Pencil, colored pencil, and gold ink on tracing paper, 8 ft. 9 in. x 30 in. (266.7 x 76.2 cm).

Each unpacker developed a check list for a gallery display that would be centered around the key object. Quickly it became clear to me that the galleries would appear quite eccentric since the check lists were not standard assemblies of material about a phase in Wright’s career, or his practice in a particular locality, but rather works that helped a particular interpreter interpret. How then to make the personality part of the display, to keep the process of interpretation itself on display. This was the role of film to capture process, a technique I had used earlier in workshops of contemporary architecture as process (Home Delivery 2008; Rising Currents 2010; Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream 2012) but had never used to make clear to a gallery visitor the process of historical thinking and archival research. Each of the participants was filmed at work: the historians in the drawings room of the Avery archives looking at the drawings and related documents unframed and in the state they are encountered by researchers; Ellen Moody, a MoMA art conservator in the museum’s conservation studio, at work on restoring the severely damaged model for Wright’s revolutionary first iteration of a tap root skyscraper, the unrealized project for a residential tower of apartment duplex units on a pinwheel plan for St. Mark’s in the Bouwerie in Manhattan (1927).

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). Model of St. Mark’s Tower. Unbuilt project. New York, New York. 1927-31. Painted wood. 53 x 16 x 16″ (134.6 x 40.6 x 40.6 cm).

Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar.

In addition to the individual contributions of those who took part in this first large scale experimental show at MoMA – and others will follow – the show has generated excitement about the possibility of discovering lesser known aspects of Wright’s career and of aspects that are meaningful today. Issues from sustainable farming to urban density to the role of ornament are as current in the debates today about architecture and landscape as they are to understanding what was at stake at key moments in Wright’s long and complex development.

Photo by Robin Holland, 2008, courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Barry Bergdoll: Curator, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art, and the Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University.