Frank Lloyd Wright + Arizona

David R. Richardson | Sep 12, 2019

Frank Lloyd Wright’s connection to Arizona, the location of his personal winter home Taliesin West, runs deep, with his architectural influence seen all over the Valley. Here, PhD student David R. Richardson gives a brief overview of several of Wright’s most notable projects in the Grand Canyon state.

From the time Frank Lloyd Wright began visiting Arizona in the 1920s until his death in 1959, he witnessed the population of Phoenix multiply tenfold, from nearly 40,000 to over 400,000 people. This burgeoning society needed architecture and civic identity, but also had its share of challenges. Early in this phase of his life he stated that “the ever advancing human threat to the integral beauty of Arizona might be avoided if the architect would only go to school to the desert in this sense and humbly learn harmonious contrasts or sympathetic treatments that would, thus, quietly, belong.” (Wright, “To Arizona,” 1940) This statement reveals a key part of Wright’s philosophy of architecture: attention to nature was essential.

The changing climate and landscape brought along with the population growth and spreading Phoenix infrastructure was keenly noticed and described by Wright’s wife, Olgivanna, in 1960, she wrote in hindsight that when they first started visiting Arizona, “the climate was mellow and sunny with very little dampness and rain. But the climate began to grow more severe in the ensuing years” (Wright, Olgivanna, The Shining Brow, 1960, p.44).

In addition to the changing climate, she also described the vanishing desert landscape. This was a challenge the Wrights found in Phoenix: what they appreciated about the desert, including the harshness of the environment, was being threatened by the arrival of more and more people.

While Phoenix was growing into a city, the Wrights encouraged learning from nature, rather than supplanting it. The desert was a source of education, it was a teacher. Wright’s descriptions and designs, often metaphorical, suggested what we might call a biomimetic learning process. He applied what he learned at the scales of building details, whole buildings, and ensembles of buildings. The desert stones would be his bricks. The desert flora would structure his architecture. The desert landscape would guide his proposals for city and society. Wright believed in architecture that was organic, integral and “of the desert” and this was at the core of his architectural offerings to the growing city.

“The desert stones would be his bricks. The desert flora would structure his architecture. The desert landscape would guide his proposals for city and society. Wright believed in architecture that was organic, integral and ‘of the desert’ and this was at the core of his architectural offerings to the growing city.”

Ocatillo Camp, Chandler, 1929

Frank Lloyd Wright began scouting out Arizona in 1928, while consulting on architect Albert Chase McArthur’s design for the Arizona Biltmore Hotel. Although not the architect of record, Wright contributed to the project with some attention-catching work and began to explore the Valley of the Sun. During this time, Wright met a patron, Dr. Alexander Chandler. Dr. Chandler was ambitious and looking to build a luxury resort, San Marcos-in-the-Desert, which was described as “the perfect desert-resort for jaded New Yorker millionaires” (Wright, “Living in the Desert,” 1949).

Ocatilla Desert Camp. Futagawa, Yukio; Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks (eds.). Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph v.5 1924-1936. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita. p.52

In order to work on this, Wright and his entourage established a camp in 1929, named Ocatillo, in an area to the east of Phoenix named Chandler after Dr. Chandler. The Ocatillo camp turned out to be a learning and testing ground for many of Wright’s ideas about building in the desert. The plan followed the contours of the land. The arrangement of the buildings made an enclosed outdoor space, an asymmetrical courtyard or plaza. There was an asymmetry, and irregularity, guided by the “dotted line” of the desert’s profiles and textures. At the time, modernist architects predominantly were using even, straight, regular lines and the resulting volumes; and in contrast, Wright used organic lines and volumes that he likened to the desert environment—one reason he stood out among the leading architects.

At Ocatillo, block prototypes were made for vertically fluted masonry meant for San Marcos-in-the-Desert. Prior to this, Wright had used textile blocks in a few of his California projects, but these were reconceived and reconsidered by studying the structural ribs of saguaros, with an intention of creating “appropriate Arizona architecture.” This lesson from the saguaro is in the cactus’s interior structure. Wright wrote that the “saguaro is the perfect example of reinforced building construction. Its interior vertical rods hold it rigidly upright maintaining its great fluted columnar mass for six centuries or more.” (Wright, An Autobiography, 1943 pp.309-310) This resort was about ready to go into construction, but due to the 1929 stock market crash the project was halted. The abandoned Ocatillo eventually disappeared as materials were taken for other uses.

Wright returned to the Phoenix area a few years later, in 1935, to build the Broadacre City model, in a space offered by Dr. Chandler called La Hacienda. In the Broadacre City model, a vision of urbanism or disurbanism was on Wright’s mind. He was thinking of utopias, cities of ideal societies. This model, created in four large sections, was shipped to New York City for exhibition at Rockefeller Center, then went on an exhibition tour to other US cities.

Taliesin West, Scottsdale, 1938

Taliesin West. Futagawa, Yukio; Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks (eds.) Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph v.6 1937-1941. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita. p.44.

In 1937, at an age of 70, Frank Lloyd Wright was willing to start from scratch in the desert. He found land in what was an undeveloped area north of Scottsdale, off (then unpaved) Shea Boulevard at the base of the McDowell Mountains. The price was $12.50 an acre, and his family and fellowship set up a new camp and started building the seasonal home for the Fellowship: Taliesin West.

Many ideas from the Ocatillo experience were refined here. Such as the architectural asymmetry, the emphasis on texture and the “dotted line.” Geology and its stratifications and striations informed the design. The desert masonry created at Taliesin West was comprised of rocks found on site and adds to Wright’s idea that buildings in the desert should be “of the desert.” With a lot of hard work, Taliesin West grew into something of far reaching significance.

From the beginning the Taliesin West experience was to be about living in the desert and what can be learned from that environment. Wright encouraged apprentices to take walks, to look carefully around them, and to thoroughly study nature in this unique setting. The fellowship would travel annually between Taliesin in Wisconsin and Arizona. Addressing the apprentices arriving at Taliesin West for the first time, Wright said “And what you should first get into your systems when you get here in the desert is to get that lesson from nature in architecture which is fundamental to the whole thing we call architecture” (Wright, “Desert Architecture,” 1954, p.177). Another innovation in the desert experience was that apprentices could design and construct their own shelters around the Taliesin West camp, experimenting with the lessons they had learned by studying nature in the desert.

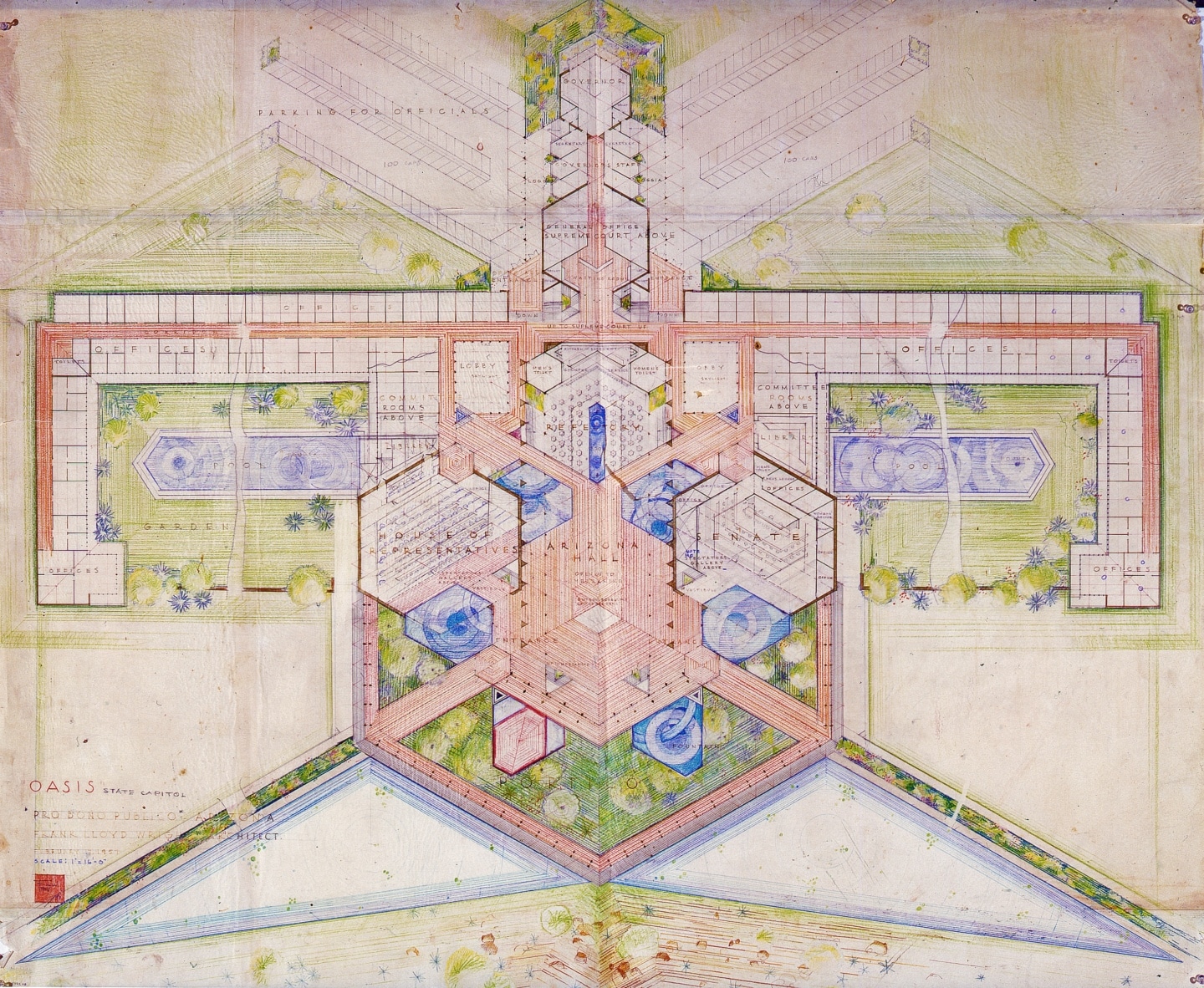

“Oasis” Arizona State Capitol, Tempe Papago Park, 1957

After living and working in Arizona for two decades, Wright continued to advocate for desert derived architecture. And when opportunities arose, he was quick to show how his vision could contribute further to the culture in the Valley of the Sun, a place he was at home and had come to know so well. When designs were widely published for a new Arizona State Capitol in 1957, Wright thought he could do much better. He sought to win the capitol commission from the architects that the politicians had chosen. He saw their plan as “a tragedy” and thought it did not have enough to say that was specific to Arizona.

“Oasis” Arizona State Capitol. Futagawa, Yukio; Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks (eds.) Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph v.8 1951-1959. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita. p.303.

As a result, Wright created and promoted his own design for the state capitol. He ran into conflict over this with the American Institute of Architects (AIA), who did not want architects competing for already awarded commissions. But Wright persisted, arguing the capitol should be selected by the people not the politicians, labelling his projected work pro bono publico (Latin: for the good of the public). To make it more democratic, since the future generations of teen-agers would inherit the state and capitol building, Wright sought their opinions by speaking at a local high school. Unfortunately, as unregistered voters, their opinions did not sway the decision makers.

Wright’s titled his design for the capitol “Oasis,” and sited it in Papago Park north of the Salt River in Tempe. What the project entailed was comprehensive, with transportation by way of moving sidewalks and shuttles across a substantial expanse of gardens with fountains. It was organized along intersecting orthogonal and hexagonal grids. The plan of the building was likened by Wright to a Thunderbird. The design raised a copper plated lattice shade canopy that had permeable openings for sunlight, for fountains and for trees to reach through. Birds would be allowed to roost, to nest, to fly through. This would have created an integral merger of inside and outside space, of building and landscape.

The winter 2020 issue of the award-winning Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, the Foundation’s exclusive magazine for members, will further explore Wright’s unbuilt works. For this unbuilt issue, we focus on Wright’s aspiration to create architecture in the public realm, for the “greater good,” pro bono publico, as he inscribed on his proposed “Oasis” capitol building design that he felt befitted his adopted state of Arizona. In the issue, released in December 2020, you will see “photorealistic renderings” of the Arizona Capitol design by David Romero. Here is just a little visual tease of what’s to come. If you’d like to receive this issue become a member of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation today.

The landscape of the Valley of the Sun was an inspiration for the capitol in another way as well, in the building’s massing and layout. A consistent theme in his work, Wright’s proposal was intended to be low, broad, horizontal; and decisively not high, tall, and vertical (as in the proposal that the politicians selected). There were, still, vertical elements in Wright’s proposal. He also envisioned radio and television broadcasting spires to top the project off, because he believed these forms of communication were vital “to the social life of the people” (“Lost Capitol of Arizona,” 1959). However, the overall massing and layout was horizontal, taking cues from the scale of the landscape around, the breadth and expanse of the valley that he believed the city of Phoenix should be in unity and harmony with.

Wright was working on Marin County Civic Center in 1957, as well, and earlier he had proposed civic centers for Madison, Wisconsin; and for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Thus, there were precedents in his own work, but the Arizona State Capitol under Wright’s designs would have been quite different. All the required governmental functions were provided for in his designs, but the treatment would fulfill his belief that, “the legislative process should be fused with the social life of the time and the place” (“Lost Capitol of Arizona,” 1959). All he and his fellowship had learned by studying the desert would come into play. What Wright intended with his proposal was a capitol which would be entirely original and distinctly different from any other state capitol building, and yet decisively appropriate to Arizona.

Wright’s Arizona State Capitol was not built, but a spire from the project was created and installed in 2004, at the corner of Frank Lloyd Wright Boulevard and North Scottsdale Road, not far from Taliesin West and has become a Scottsdale landmark.

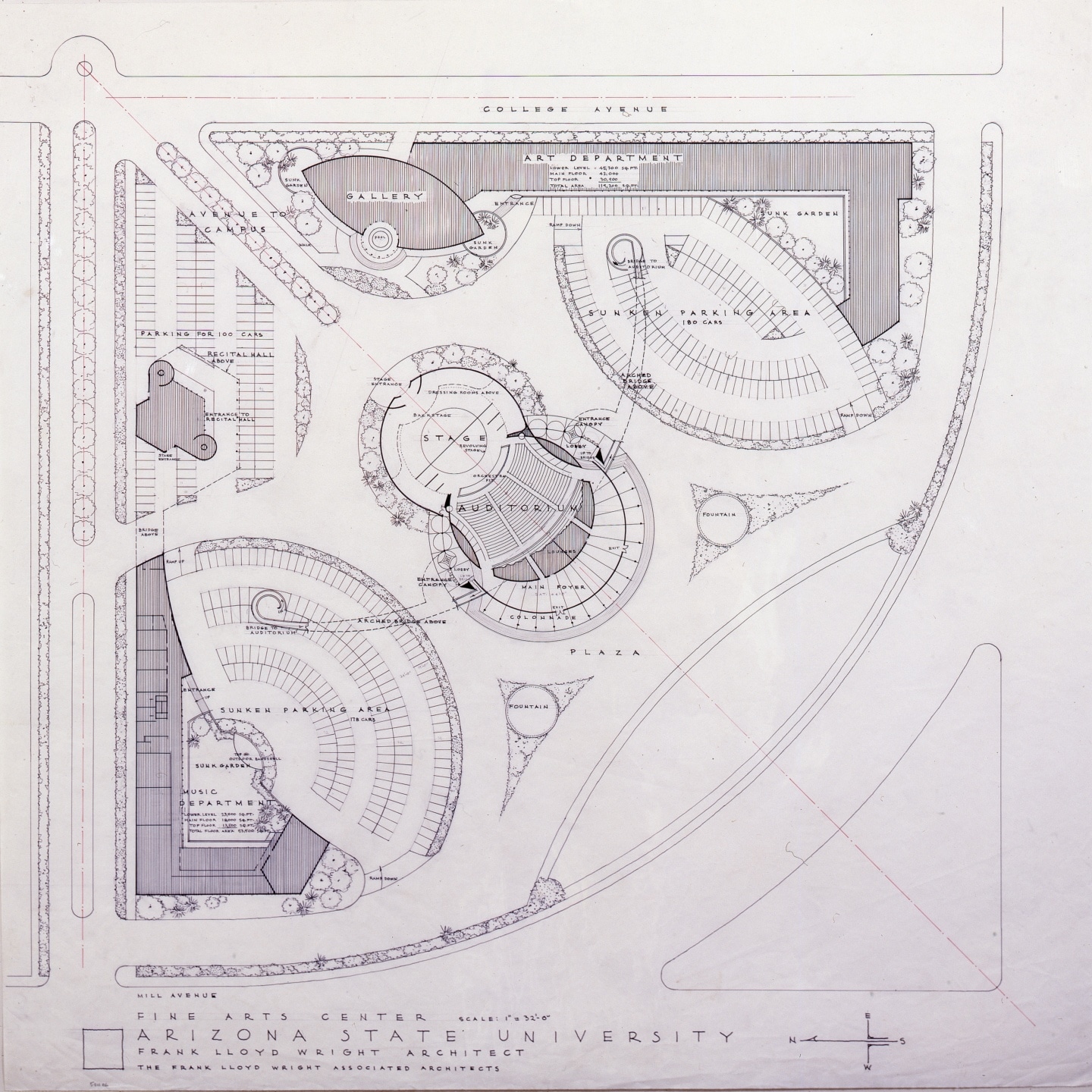

Fine Arts Center [proposal] and Gammage Auditorium, Arizona State University, Tempe, 1957

Fine Arts Center [proposal] and Gammage Auditorium, Arizona State University, Tempe, 1957. Futagawa, Yukio; Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks (eds.) Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph v.8 1951-1959. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita. p.367.

The published drawings and information on Frank Lloyd Wright’s proposals for the Arizona State Capitol, caught many people’s attention, including President of Arizona State College, Grady Gammage. In 1957, Wright and Gammage were introduced by journalist Lloyd Clark who had covered Wright’s State Capitol designs in the newspapers.

The college under Gammage’s leadership was changing in significant ways, including the milestone that during his presidency, the name and designation officially became Arizona State University (ASU) by way of a vote in 1958. Wright recognized the importance of Gammage’s work and wanted to take part and contribute to the growth and reshaping of the university, and mutually, Gammage was interested in commissioning Wright to build an auditorium and fine arts center.

When considering a site, Gammage and Wright visited the southwest corner of the campus at the intersection of Apache boulevard and Mill avenue in Tempe. Wright is said to have made a gesture with open arms like an embrace, and to have said the building should convey the expression “Welcome to Arizona” (Siry, “Wright’s Baghdad Opera House and Gammage Auditorium,” 2005, p.282). This gesture was an early hint at the gesture the auditorium would be designed to make with its access bridges. The site in Tempe happened to be on the southern side of the Salt River, not far from where Wright had planned the Arizona State Capitol in Papago Park site on the north bank.

Wright had planned more buildings than were realized on the site. He had planned: the auditorium, recital hall, music department, art gallery, art department, gardens, fountains. Wright’s earliest designs included a broadcasting spire atop the auditorium, so that what was on stage could be transmitted to a much wider audience. Another significant change in the development of the plans was that instead of all the initially planned buildings crowded on one site, most of the area around the auditorium’s site became park space or parking spaces. Later, after the successful posthumous completion of Wright’s designs, Taliesin Associated Architects and William Wesley Peters were hired to build facilities for the music school on an adjacent site.

While neither Wright nor Gammage lived to see the project built, what they set in motion would become Gammage Auditorium, a renowned destination for performing arts. Through this project, Wright and Gammage both furthered their civic legacies.

Always inventive, Frank Lloyd Wright had an abundance of ideas for living and flourishing in the desert. These ideas were meant to lead Phoenix’s swiftly growing population to a more graceful way of life in harmony with the desert environment. Wright’s ideas were formulated in many ways—in writing, in artworks, in drafts of various projects, in residential living experiments—and then applied to his highly ambitious efforts at civic and social architecture. Wright designed single family homes throughout his career, yet he also sought to help inspire and benefit people around him, in the public realm, when possible. The hardships and difficulties of the climate in the Arizona desert provided ideas and creative solutions by way of understanding “the open book of nature” (Wright, “Desert Architecture”, 1954, p.177) as well as aspiration to make architecture for the greater good, pro bono publico.

David Richardson is a PhD student in architectural history, theory, and criticism at Arizona State University. He has degrees in architecture and in philology and is working on several projects about architectural education.

Bibliography

Brierly, Cornelia. “Taliesin West: The Early Years.” Frank Lloyd Wright quarterly. Vol.3, no.4. Fall, 1994. Clark, Lloyd. “Frank Lloyd Wright and the Arizona Capitol.” The Journal of Arizona History, vol. 55, no. 1, 2014, pp. 103–106. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24459864. Friedland, Roger, and Harold Zellman. The Fellowship: The Untold Story of Frank Lloyd Wright & the Taliesin Fellowship. New York: Regan. 2006. Gray, Jennifer. “Reading Broadacre” The Whirling Arrow: News and Updates from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. October 1, 2018. Accessed Online: https://franklloydwright.org/reading-broadacre/ Parachek, Ralph E. Desert Architecture. Phoenix: PARR of Arizona. 1967. Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks. “The Lure of the desert”. Frank Lloyd Wright quarterly, 1999 Fall, vol.10, no.4, pp.4-9. Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks. “Frank Lloyd Wright’s encounter with the desert“. Frank Lloyd Wright quarterly, 2005 Winter, vol.16, no.1, p.[2]-23. Price, Jay M. “Capitol Improvements: Style and Image in Arizona’s and New Mexico’s Public Architecture.” The Journal of Arizona History, vol. 41, no. 4, 2000, pp. 353–384. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41696605. Siry, Joseph M. “Wright’s Baghdad Opera House and Gammage Auditorium: In Search of Regional Modernity.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 87, no. 2, 2005, pp. 265–311. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25067172. Solliday, Scott. “Wright’s first desert adventure“. Frank Lloyd Wright quarterly. vol.2, no.1. Winter, 1991. p.8-10. Spencer, Brian A. “Ocotillo” Journal of the Taliesin Fellows. no.34. Summer, 2009. p.14-21. Wright, Frank Lloyd “To Arizona” In Arizona”, Arizona Highways, 1940. pp.6-15. Wright, Frank Lloyd “Living in the Desert” Arizona Highways, October, 1949. pp.12-15. Wright, Frank Lloyd. An Autobiography. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1943. Wright, Frank Lloyd, and Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer. ”Desert Architecture” (November 28, 1954). “Creating Architecture: A State Capitol for Arizona” (February 10, 1957). Frank Lloyd Wright, His Living Voice. Fresno, CA: Press at California State University Fresno, 1987. Wright, Olgivanna Lloyd. The Shining Brow: Frank Lloyd Wright. New York: Horizon Press, 1960. “Arizonans Split on Wright Plans; Architect’s Ideas for New State Capital Arouses a Storm of Controversy.” The New York Times. April 7, 1957. “Proposed state capitol for Arizona by Frank Lloyd Wright.“ Architectural Forum. April, 1957. “The Inside Story of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Greatest Unbuilt Building, the Lost Capitol of Arizona.” Pacific Arts Association Bulletin. Summer, 1959. p.14-19. “Frank Lloyd Wright and Arizona”, “We Found Paradise”, “Cross-Country Caravan.” Frank Lloyd Wright quarterly Vol.9, no.1. Winter 1998. “Frank Lloyd Wright in Arizona.” Frank Lloyd Wright quarterly Vol.23, no.1. Winter, 2012. Commemorative Issue.