Connections between Frank Lloyd Wright and L. Frank Baum

Kyle Dockery | Jan 7, 2025

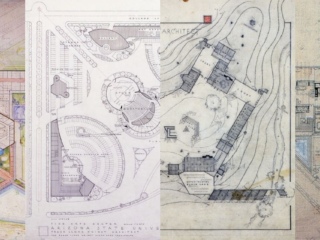

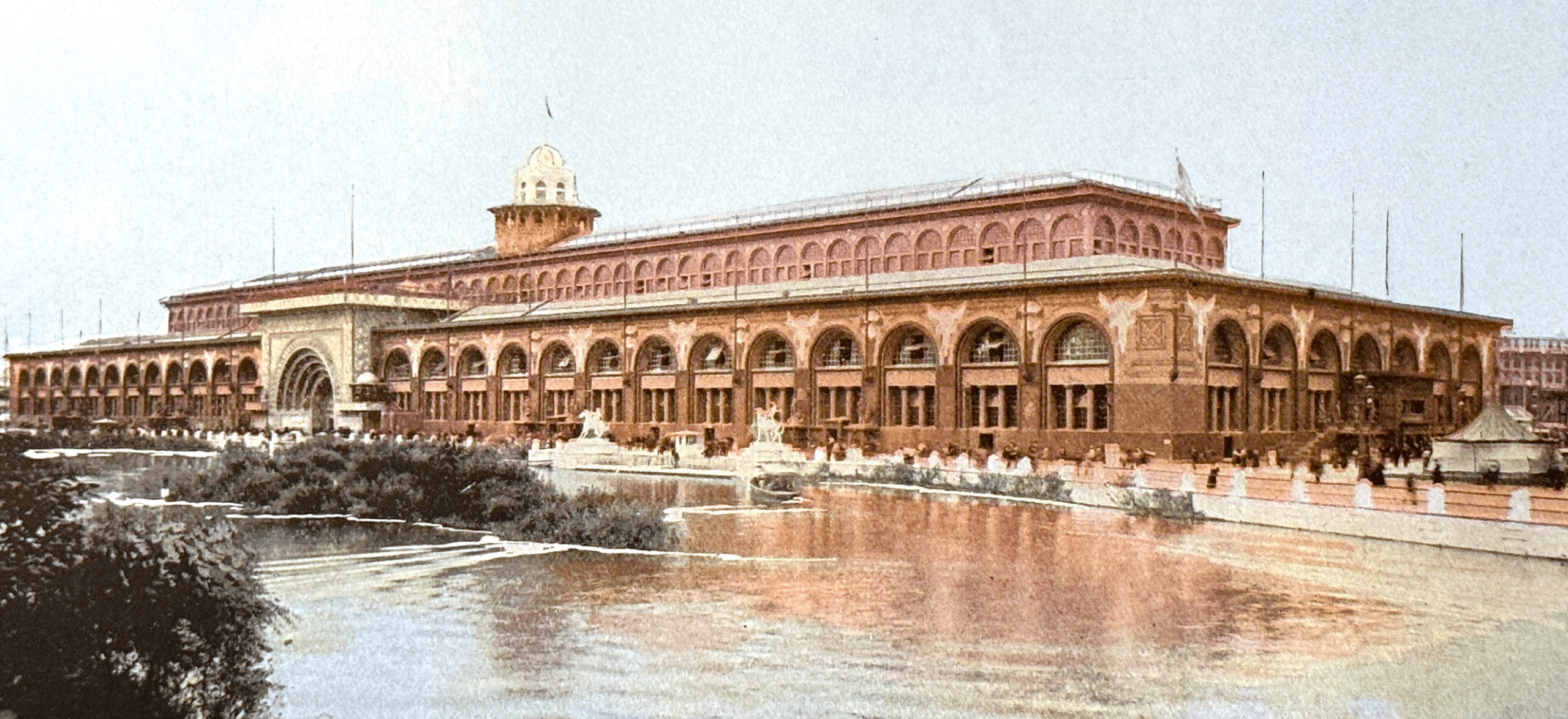

Architectural Digest did an interview with Nathan Crowley, the production designer of the film Wicked (2024) where he discusses the technical challenges and artistic influences of the project. He calls out Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building as a reference point for the entrance to the Emerald City and Carlo Scarpa for parts of the Wizard’s palace. After seeing the film I can’t help but think there may have been some Wright influence, via the textile blocks, on some of the Emerald City’s textured walls.

Watch the entire video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Qp4tLTrX6A

Louis Sullivan’s Transportation Building. Picturesque World’s Fair, An Elaborate Collection of Colored Views—Published with the Endorsement and Approval of George R. Davis, 1894. Chicagology.com

Somewhat surprisingly, the classic 1939 Wizard of Oz film was not shown at Taliesin until 1949. The Taliesin Fellowship presented films almost every week when residing at Taliesin, which included a mixture of new, arthouse, and foreign films—a total of more than 1,200 films between 1933 and 1959. The Wizard of Oz was likely overlooked upon release due to poor timing. The Fellowship left for Taliesin West in late September 1939 and didn’t show another film until May of the following year when they returned to Wisconsin. By the late 1940s, the Fellowship’s demographics were changing, as many of the early apprentices now had young children, which led to more family-oriented programming and fewer foreign films.

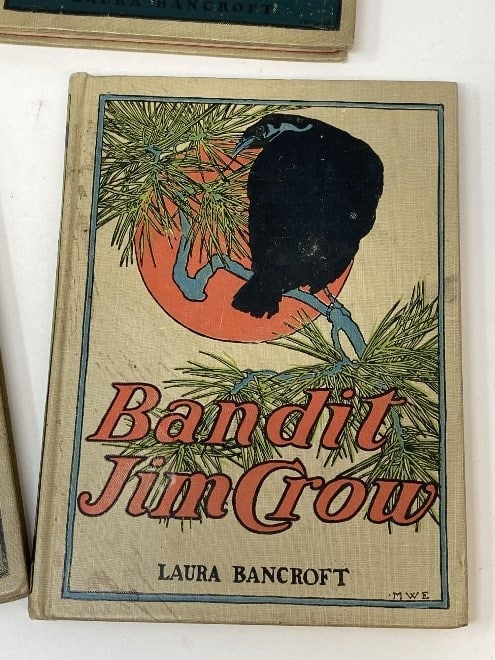

L. Frank Baum worked with Wright’s sister Maginel Wright Barney and her first husband, Walter Enright, on multiple books, although none were part of the Oz series.

Publicity still showing main characters from 1939 version of The Wizard of Oz. Hollywood: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1939. Copyprint. Motion Picture, Broadcasting, & Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress (37)

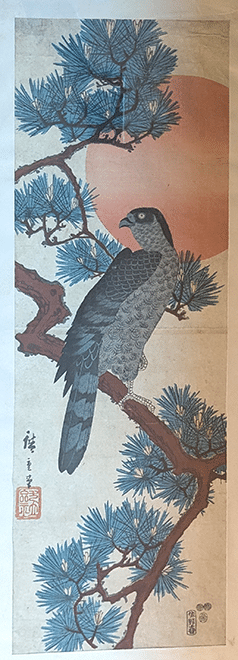

The first set was The Twinkle Tales, published with the pseudonym Laura Bancroft, one of six pen names he used over his career. They were first published in 1905-1906 as six separate books and then as a single volume in 1911. Maginel did the illustrations, including the covers. The cover for the first edition of Bandit Jim Crow appears to quote Hiroshige’s famous print of a hawk, perhaps showing the influence of her older brother’s growing love of Japanese art.

2023.044.1

Maginel Wright Barney

In 1907, Walter illustrated Baum’s Father Goose’s Cookbook while Maginel illustrated the book Policeman Bluejay, written again under the Bancroft name. In 1910, Maginel and John R. Neill provided illustrations for L. Frank Baum’s Juvenile Speaker: Readings and Recitations in Prose and Verse, Humorous and Otherwise.

Although it is not known exactly how Walter and Maginel were introduced to Baum, they were all connected to the tightknit Chicago publishing industry. Not long after Wright started his family in Oak Park, Maginel and her mother Anna moved into the house next door. Maginel took one year of classes at The Art Institute of Chicago and then spent three years honing her craft as an engraver at the Barnes-Crosby company after which she married Walter J. Enright and began working independently.

Baum’s early books were published by two Chicago companies, the George M. Hill Company and Reilly & Britton and their illustrators all Chicagoans. The illustrator of the Wizard of Oz, W.W. Denslow, had an office in the Fine Arts Building, where Wright once had an office and was a frequent visitor. Ralph Fletcher Seymour, also based in the Fine Arts Building, provided illustrations for Baum’s American Fairy Tales and later published the first book Wright wrote, The Japanese Print. In her memoir, The Valley of the God-Almighty Joneses, Maginel vividly describes a visit to the Studebaker Theater, located in the Fine Arts Building.

“Sometimes, tired and dusty, [Wright] would call me and say. “Sis, get some of your friends and we’ll all go in to [sic] the theatre.” So I’d get a girl and a couple of boys and we’d take the train to Chicago to the little Studebaker Theatre where something by Gilbert and Sullivan was always playing. We would occupy one of the middle rows, and it wouldn’t be long before the whole company was playing to us, Frank’s gay gargantuan laugh filling the whole theater. Afterwards we went to the Hofbrau, and late at night, spent with laughing and enjoyment, we took the train back to Oak Park.”

Another Wright connection—this one more distant—centers around the Garrick Theater. This building, designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler, was built in 1891 when Frank Lloyd Wright was one of their leading draftsmen. Wright played a large role in designing the building’s ornate façade and rented an office in the building when he began his independent studio. In 1905, pleased with the success of the 1903 Broadway production The Wizard of Oz, Baum launched his second musical at the Garrick Theater.

The Garrick Theater Building was designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler of the firm Adler & Sullivan for the German Opera Company. Original LOC image description: 7. Historic American Buildings Survey PHOTOCOPY OF PHOTOGRAPH C.1900 – Schiller Building, 64 West Randolph Street, Chicago, Cook County, IL

Titled The Woggle-Bug, it was an adaptation of the second Oz novel, The Marvelous Land of Oz, which had been published the year before and has no relation to the story of Dorothy and friends. The musical was poorly reviewed and closed after less than a month, though much of the music composed by Frederic Chapin (not to be confused with the more famous Polish composer Frédéric Chopin) would go on to do well as published sheet music.

The header image is a still frame capture from the Architectural Digest video interview with Nathan Crowley.