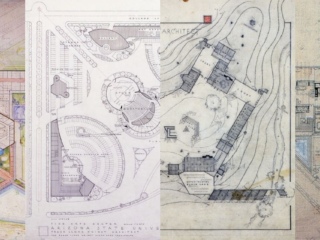

Architecture Student Builds Rammed Earth Shelter at Taliesin West

Conor Denison | Apr 12, 2019

When Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fellowship at Taliesin and Taliesin West was first developed, architecture students learned by doing, when they created their own desert shelters to live in. Today, this tradition lives on through School of Architecture at Taliesin students. Conor Denison recently completed his shelter, which incorporates the ancient sustainable building method of rammed earth. Here he dissects the process of creating and building the shelter from start to finish, and what he learned along the way.

Tell us a little about yourself.

I was born and raised in Toronto, Ontario. After graduating from high school, I went on to study Geography at the University of Western Ontario. On the wall of the Geography department were the words “Know Your World” – I thought this was a nice summary of what my studies were focused on. I went on to do a workshop at Arcosanti, during which I took a tour of Taliesin West. My friend Zoe said to me “I could see you going here,” and I agreed with her. I enrolled at the School of Architecture at Taliesin the following fall.

Tell us about your shelter. What inspired the creation and the name? What is the shelter made of and how does it relate to the site?

The name of the shelter is branch, which is in honor of my mentor and teacher throughout this process, Quentin Branch. Quentin began building with rammed earth over 40 years ago, and I had the benefit of having his experience and expertise to learn from throughout the project – from ideation through creation. The entire structure is rammed earth – the floor, bench, walls, and roof; creating one continuous mass. Most people thought it was ridiculous to use rammed earth as a roof – of course it is – but Quentin helped me to realize it. Openings and voids in the earthen form allow for inhabitants, airflow, and light to enter.

I was interested in the fact that the shelters are only used as student dwellings for half the year, and for the other half of the year they exist in the Sonoran Desert as something else entirely, separate from human use. The idea was to create something with ecological consideration which is significant beyond its use as a student dwelling.

The form ties were used to hold the interior and exterior forms in place at their designed thickness. Typically these ties are snapped or cut off, but after removing the forms, I decided to leave many of the ties in place. Inside they create opportunities to hang things, and on the exterior they break up the mass, creating dynamic shadows throughout the day. The ties and form panel outlines express the construction method.

How did the site you chose impact the design of your shelter?

The site of branch is an existing 8’x8’ concrete pad, which served as the basis for the design. This existing pad was used as the interior footprint of the shelter, and we added a footing around the perimeter for the walls to be built upon. The concrete pad had a short masonry base wall, and this wall had an opening in it on the east side for entry. The wall was not stable enough to use in my project, but the location of the entry was kept the same. When we are designing, we talk a lot about context, and I spent a lot of time thinking about what this word means, what its scope is, and how I could create something that was contextual in a meaningful way.

How long did the process of creating and building the shelter take you from start to finish?

When we started the school year in Spring Green in August 2018, I was working to develop a position for my thesis. The months of August through October were spent reading and refining the scope of my project. When we migrated to Arizona in October, picking a site and living in the desert again was an important prompt for me to begin designing. The design process took place for the most part during the months of October through December. The construction phase took five weeks in total – one week digging and pouring the new footing, and four weeks of forming and ramming. In total we packed the forms with 45 tons of decomposed granite over these four weeks.

All photos by Conor Denison.