A Capitol Controversy

Rebecca L. Rhoades | Feb 14, 2021

Arizona-based journalist Rebecca Rhoades tells the captivating story of Frank Lloyd Wright’s design for the Arizona Capitol that never came to be, brought to life with photorealistic renderings by Spanish architect David Romero.

“What could be more ridiculous than for Arizona to go on record before the world and our own descendants as having rejected Frank Lloyd Wright as an architect?”

“What could be more ridiculous than for Arizona to go on record before the world and our own descendants as having rejected Frank Lloyd Wright as an architect?”

The question, part of a letter to the editor to the Phoenix Gazette by local resident Halpin Gilbert, expressed the sentiments of many concerned Arizonans at the time. It was April 1957, and the entire city, it seemed, from legislators to school students, was embroiled in a battle over the future design of the State Capitol. At the center of the dispute was Wright himself, whose unsolicited—and for many, radical—proposal dominated conversation and media coverage and divided neighbors and family members for much of the year. For the architect, it was a gift to the people of his adopted home state, but following months of public contention, his visionary plans never made it off the drawing board.

Render by David Romero

The controversy surrounding Wright’s proposition underscores Arizona State Capitol’s long and turbulent architectural history that one has been referred to as “penny-pinching” and “patchwork.”

The original copper-domed Beaux-Arts structure that many to this day think of as the capitol was built in 1900, when the state was still a territory. Today, it houses the Arizona Capitol Museum. Constructed of Southwestern materials, including black Malpais basalt, granite and tufa, the diminutive structure, which measures 184 feet long and 84 feet deep, was built for just slightly more than $100,000, despite opposition from taxpayers who denounced it as a “useless extravagance.” A second design, a larger neo-classical edifice with a towering central dome, similar in style to the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., was rejected as too costly. And in the mid-1910s, Governor George W.P. Hunt’s proposal to add Taj Mahal-type pools and landscaping to the exterior also ran afoul of financial restraints.

By the mid-1950s, the building was showing signs of structural problems, including leaking, pest infestations, and a lack of proper heating and cooling. A survey conducted at the time found that by the 1970s, the small statehouse would need to more than double in size in order to accommodate the growing number of employees. “It is outmoded and outdated … and it is ugly,” the Arizona Republic editorialized. “What this state needs is a capitol building of which the people can be proud; one that will stand as a monument to the progress and progressiveness of Arizona.”

The state legislature authorized then-Governor Howard Pyle to secure plans for modernization and expansion. Pyle sought bids from a collective of architects known as Associated State Capital Architects (ASCA). The group comprised principals from four regional firms—Lescher and Mahoney, Edward L. Varney Associates, H.H. Greens, all from Phoenix, and Place and Place of Tucson—as well as a few draftsmen, according to ASCA architect Henry Krotzer, Jr.

Renders by David Romero

When Ernest W. McFarland replaced Pyle in 1955, he created a Planning and Building Commission to oversee the construction of state office buildings. Instead of accepting additional proposals, the commission entered into a new contract with ASCA, which submitted a dozen different plans. The winning design was a nondescript 20-story office tower flanked by low wings that would accommodate the House and Senate. Shaped like an inverted T, the structure, which was estimated to cost approximately $8 million to build, would be placed directly adjacent to the existing Capitol. In a nod to classical architecture, McFarland insisted that the central tower be topped with a dome.

Following publication of the new building’s designs in the Phoenix Gazette, reporter Lloyd Clark thought it would be nice to give Wright an opportunity to express his views on the proposed new building. The architect’s response? “Why comment?” he said. “The thing is its own comment on Arizona and Phoenix.” Intrigued by the answer, Clark sought out a follow-up meeting with Wright, and on a cold Tuesday morning, the pair met at Taliesin West. Never one to mince words, Wright declared the monolithic structure “a telephone pole with a derby hat and two wastebaskets for the legislature.”

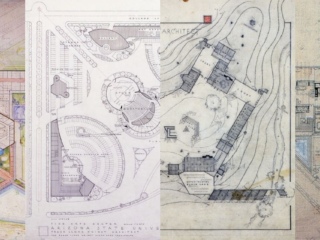

Dissatisfied with the “commonplace nature” of ASCA’s design, Wright during the meeting began sketching his own plans—one elevation and one floor plan—for an expansive one-story shelter that was an antithesis to the austere skyscraper in the city. He envisioned a complex that would serve as the Grand Canyon State’s response to Alhambra, the grand 14th-century fortress of Moorish kings in Granada, Spain. Consistent with his concept of organic design, it would speak of Arizona. He called it “Oasis,” and because it would be a welcoming place for residents and visitors alike, Wright inscribed his drawings with the motto “Pro Bono Publico”—for the benefit of the people. He told Clark at the time, “In all my efforts, I have never done anything for the people whose community I have enjoyed for 25 years. I want to do something about that.”

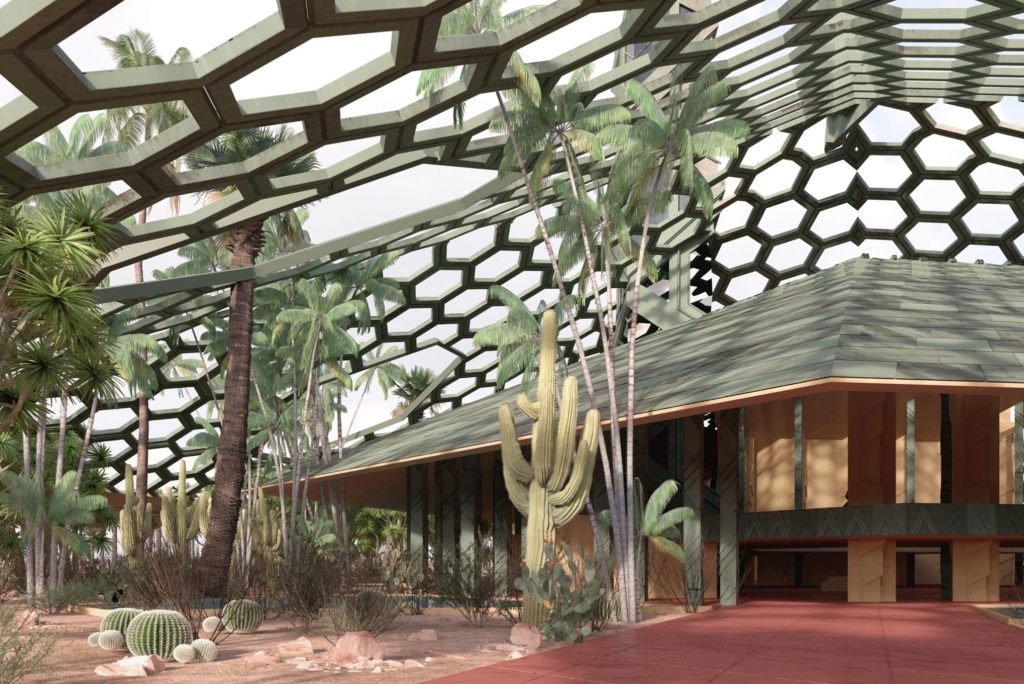

Render by David Romero

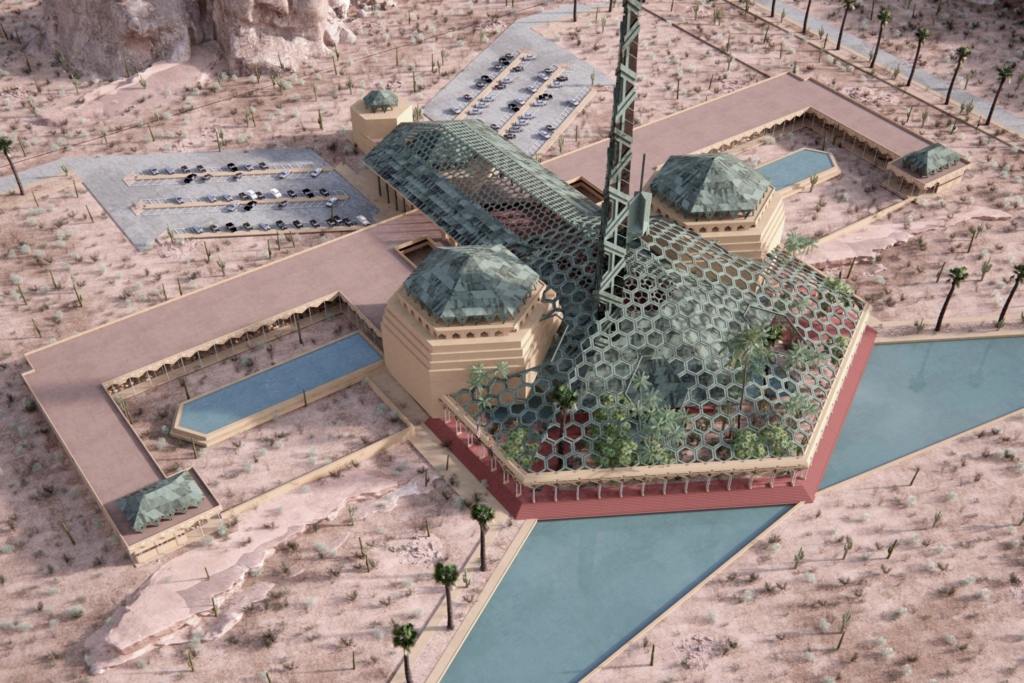

A defining feature of Wright’s design was a 400-foot-wide lacy dome of reinforced perforated concrete plated in blue oxidized copper that would filter sunlight “like the foliage of a great tree,” the architect explained. Under the open hexagonal lattice, which would be supported by a colonnade formed of native onyx, the architect visualized lush botanical gardens teeming with native flora that would eventually grow up through the honeycomb ceiling, further unifying the built environment with the landscape from which it arose. A pair of fountains would shoot through the open lattice, connecting the interior spaces to large reflecting pools that front the geometric structure. Wright claimed the sheltering design would reduce dependence on air-conditioning.

In the center of the gazebo-like creation, the architect placed a large glass-enclosed atrium that he called the “Arizona Hall,” which would display paintings, murals, and exhibitions by Arizona artists. Two hexagonal domed halls flanked the core structure. Sheathed in blue copper, they would accommodate the House and Senate.

Wright’s initial rendering featured two spires—ornate radio and TV antennae—jutting like horns from each side of the dome. It was later changed to a single tower element, its offset placement breaking up the otherwise symmetrical design.

He called it “Oasis,” and … inscribed his drawings with the motto “Pro Bono Publico”—for the benefit of the people.

Because Wright believed that a city should place important buildings at various locations, creating several focal points, he sited his creation in Papago Park. Located about 10 miles from downtown Phoenix, the park, with its hundreds of acres of distinctive red sandstone outcrops and otherworldly rock formations, afforded the open spaces and awe-inspiring vistas that Wright imagined for his design. “It provides a beautiful, natural, and fitting backdrop,” he stated.

Within a week of developing his design, Wright and his apprentices had developed a promotional scheme for Oasis. Although he was not invited to present his ideas, and although a proposal had already been accepted by the commission, Wright unveiled his ideas during a widely publicized press conference at the grand Westward Ho Hotel. Responses were polarizing.

State officials denounced the design, calling it “too ornate” and “too expensive,” even though its estimated cost was $5 million, $3 million less than the proposed skyscraper. One legislator went so far as to say that the Oasis looked like an “oriental whorehouse.”

The members of ASCA, as well as the American Institute of Architects (AIA), objected to Wright campaigning for a commission that was already theirs, an action that goes against an unspoken code of conduct among architects. In a March 6, 1957 article in the Arizona Republic, Albert B. Spector, attorney for ASCA, referred to Wright as an “egocentric individual who believes that only he has been endowed with the touchstone of architectural insight.”

Render by David Romero

But others saw value in Wright’s proposal. The Chamber of Commerce in Nogales supported his plan. In a letter to the editor in the Arizona Republic, renowned Scottsdale artist Lon Megargee wrote, “The genius creates an original, distinctive design—pleasing to the eye, harmonious in its relationship to the terrain, and practical in its application to the needs of the state and the people.” Taliesin Fellow and Wright apprentice Charles Montooth noted, “No sensible person would seriously question our most experienced architect’s artistic judgment any more than he would question the artistic judgment of Bach or Rembrandt. No sensible person would question the suitability of the proposed building for its desert site. … To accept mediocrity when greatness is offered is to degrade ourselves.”

To bolster his case, Wright solicited the views of teachers and students at area schools; the responses were overwhelmingly favorable. Ralph Wolff of Camelback High School, noted, “This type of structure will help to beautify the State of Arizona. … It not only is approximately one-half the cost of the proposed aberration but is extremely functional for our locality and climate.” Sandy Miller agreed. She wrote, “I feel that more than any other building, the Capitol should adhere to the natural surroundings of its state. … This subordination between building and Arizona desert and mountain is very well-established by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright.”

Renders by David Romero

“… No sensible person would question the suitability of the proposed building for its desert site. … To accept mediocrity when greatness is offered is to degrade ourselves.”

Hundreds of students wrote letters to Wright expressing similar statements. Some felt that the complex’s modern characteristics and the fact that it was designed by the celebrated architect would attract tourists to the state. Others praised the timeless appeal of the organic design and its ability to integrate seamlessly into the rocky surroundings. Those who did not favor the scheme suggested alternative architectural styles, such as Santa Barbara, and lamented the possible loss of native parkland.

For months, area newspapers brimmed with articles, opinion pieces, and letters analyzing both sides of the issue. There were radio and TV interviews, and even public debates. One member of the public, who signed his letter to the Arizona Republic “Another Old Tax Payer,” commented, “Tourists don’t come here to see beautiful Capitols. They come because Arizona is different from their home state—different social atmosphere—different climate. Because they can see a Papago Park without a Capitol on it.”

As the controversy continued and support of Wright’s plan grew, state officials searched for reasons to disregard his proposal, and they were quick to pick up on a legal concern related to moving the Capitol to Papago Park. Because the park was outside city limits, the legislators said it was in violation of the Arizona Constitution, which noted that if the land on which the original Capitol was built was not used for its intended purpose, ownership could revert back to the families who deeded it.

According to Montooth, a growing number of interested citizens banded together to start a petition drive to put the matter to ballot and delay the final decision until January 1958, causing concerns among the commission and legislature that voters would approve Wright’s proposal. The officials sought a hasty compromise.

Render by David Romero

The new plan would forgo the modern tower and simply feature two wings to be constructed on the existing Capitol. The cost would be around $2 million, which was available to the commission through unrestricted funds that did not require legislative approval. While members of AIA, the Arizona Society of Architects, and some members of the state legislature protested both the speedy decision and building design, the commission voted to proceed. Within days, soil test holes were drilled and excavation was started for the foundation and basement of the new structures.

Ultimately Wright lost his bid, although according to Montooth, he did not appear to expect much to come from the proposal. “From the twinkle in his eye, I think he enjoyed all the excitement he created,” he said. The architect went on to design the Grady Gammage Memorial Auditorium on the Arizona State University (ASU) campus. In an ironic twist, the concert hall, which was constructed posthumously following Wright’s death in 1959, now attracts more visitors than the Capitol.

Perhaps the late Stewart Udall, former Arizona congressman and secretary of the interior, sums it up best. In the April 1969 issue of Arizona Review, an ASU publication, Udall wrote about Wright’s capitol design: “Had the building materialized, architects and designers would have come to see it from far away, just as they stop off now to see his auditorium on the ASU campus. If we had cared enough, we might have had the most exciting state capitol in the nation.”

Rebecca L. Rhoades is an award-winning writer who specializes in architecture, design, art, and travel. Her work has been featured in a variety of publications, including Phoenix Home & Garden, PHOENIX magazine, Su Casa, Via, and AAA World.

David Romero is an architect and the artist behind Hooked on the Past, a project driven by his two loves: the history of architecture and the world of computer generated images. This is the third of his “Unbuilt” collaborations with the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. Find more of his work here.