Willey House Stories Part 4 – A Bridge Too Far

Steve Sikora | Mar 15, 2018

Every house has stories to tell, particularly if the house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Some stories are familiar. Some are even true. Some, true or not, have been lost to time, while others are yet to be told. Steve Sikora, owner of the Malcom Willey House, continues his exploration of the home and its influence on architecture and society.

As new Wright homeowners in 2002—still green as grass—one of the facts shared with us, regarding the significance of our particular house in Frank Lloyd Wright’s vast portfolio, was that it represented a sort of bridge between Prairie and Usonia, the two great epochs in his career. A prominent source for this assertion was the 1993 edition of the Frank Lloyd Wright Companion, one of the first books we acquired on the subject of Wright. In it, William Allin Storrer wrote that Willey “represents the major bridge between the Prairie style and the soon-to-appear standard L-plan Usonian house.” His commentary was preceded by John Sergeant, in his 1976 book on Usonians “(Willey)…marks a fascinating link between Prairie houses on the one hand, and Usonians on the other, which it evokes in its untouched materials (cypress and brick), simple fireplace, brick-covered floormat, and prototype living room-bedroom ‘tail’ plan.” We accepted this premise unquestioning, since the idea was not only sung by the local, evangelistic choir, but was also committed to peer-reviewed print, in multiple publications. It was gospel. Aspiring to become appropriately devout acolytes, but beset with concerns over plugging leaks, sourcing old growth cypress, locating plans and collecting the correspondence between the Willeys and Taliesin, we added the bridge concept to our talking points. Only now, some 16 years after this journey began, is it time to question the metaphor.

Street view from the northwest. Nancy Willey’s photo album.

In Storrer’s observations, the Prairie house planning vocabulary was based on a cruciform or pinwheel plan, while the Usonian vocabulary was primarily an L-shaped layout or pollywog. The Willey House was where that particular deviation in planning vocabulary occurred. So, I guess that qualifies it as part Usonian. The general consensus told us that Prairie houses had pitched roofs with deep overhanging eaves. Willey had one of those. Maybe that was the reference to the Prairie side of the bridge. But then again, most every Usonian house in the Twin Cities had one too. The Neils House (1949), the Oldfelt House (1958) and the Lovness Cottage (1959) all featured pitched roofs. In fact, only the Lovness Studio (1955) was designed with the Usonian convention of a flat roof. So, it would seem, a pitched roofline, in and of itself does not delineate between Prairie and Usonia.

Books dedicated to the Usonian house sometimes included Willey as a precursor, but as often as not made no mention of it whatsoever. As I learned more about the genesis of the house I found this curious, because Willey seemed to be seminal. So, when I met Eric Lloyd Wright at a Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy conference and he said “Ahh the Willey House, the first Usonian,” I was disinclined to argue with him.

On Willey House tours, I use contrasting slides to illustrate the difference between the two great periods in Wright’s work: the Heurtley House (1902) as the Prairie house example and Jacobs I (1936) as the Usonian. The stark contrast is instantly evident to everyone. In a general sense—which is the only way to talk about these typological extremes—Prairie houses were spacious and symmetrical. The main entrances were usually evident if not pronounced. Because they faced the street like Heurtley, Prairie houses sometimes featured a front porch where the family could sit and exchange pleasantries with the neighbors passing by. Prairie houses made extensive use of art glass adorned with abstracted natural forms. Sometimes this pattern grammar extended to other furnishings that might include rugs, fixtures, murals, sculpture and, of course, furniture. The inhabitants of a Prairie home were surrounded by abstract depictions of the natural world. From a plan perspective, the box was already beginning to disintegrate and interior spaces flowed gracefully into one another. Usonians by contrast were minimal houses, in comparison wildly asymmetrical. Stripped of unnecessary adornments, any ornamentation was integral to the design of the house—like perforated wood boards and skylights or ceiling trim. Wright’s integral ornament may also include characteristics of natural materials employed such as wood grain, brick or stone texture. The houses were generally smaller, more utilitarian (or automatic), ever more free-flowing within, and usually open to protected outdoor precincts. But the differences were greater than plan or aesthetic. In Wright’s organic architecture the client factored into the design of a house as much as the site, materials and budget did. One of the most profound differences between the two periods was cultural. Twenty years had elapsed between the two eras. Prairie houses were typically built for a wealthy clientele, while Usonians were intended to serve the burgeoning middle class. The clients of Prairie houses insisted on the social formalities befitting a prosperous businessman, at the dawn of the 20th century. They included servant’s quarters and formal entertaining spaces, parlors, drawing rooms, libraries and living rooms. Maximum design attention was lavished upon the public spaces. The private spaces were less ornate and the service areas of the house were usually downright plain. The Usonian house was both more guarded from the approach side, and considerably more open on the private side of the house. The front door was sometimes intentionally difficult to find. Nature was strongly implied within the Prairie houses, but Usonians provided direct experience with the natural world courtesy of floor-to-ceiling French doors that conjoined living and garden spaces. Usonian houses were designed for mid-twentieth century, casual living. Further, the inhabitants of Usonia wouldn’t employ domestic servants so every room needed to be an equal balance of beauty and utility.

Willey House scheme 2 plan view.

The idea of Willey somehow bridging the multi-decade gap between Prairie and Usonia seems like an incomplete thought to me. A bridge implies that there is a great leap to be made from one point to the other. The problem with that concept is that world events and Wright’s explorations during the intervening years directly contributed to how he arrived at Point B. Think of all that had occurred between the end of Wright’s Prairie years (assuming they ended shortly after his return from Europe) and Jacobs 1. The world was enflamed by World War I, the decline of the Arts & Crafts Movement and the rise of modernism, women’s right to vote, the financial recklessness of the Roaring ’20s, prohibition, the Great Depression, the dust bowl, the inception of government social programs, labor organization and the rise of the middle class. In terms of Wright’s built works; he achieved some impressive milestones during this interval including Taliesin I and II, Midway Gardens, the A.D. German Warehouse, Olive Hill, the Imperial Hotel, all of the California block houses, and the list goes on.

Picking an end date for Prairie is difficult. If we are to believe Wright, his Prairie period wasn’t even wrapped up before Usonia began. He claimed that his final Prairie house was Wingspread for Herbert Johnson in Racine in 1937 (3 years after Willey). The aesthetic of Wingspread was certainly not classic Prairie. But obviously, the pinwheel plan was.

To further muddy the waters, there is a relationship between Willey and much of the interstitial work done by Wright from the teens through the thirties, namely the many textile block constructions. The Willey House is a profoundly monolithic structure, though not made of concrete block. Alternating bands of the self-similar, red brick are used inside and out, lining the fireplace, paving the driveway, and extending out as protective walls. The living room floor extrudes out from beneath the French doors, creating the prow-shaped terrace, then follows along the side of the house in both directions, forming pathways. A single material folding and flowing like a brick rapids all the way down to the street in a form of a stunning, walled staircase. The feeling is as if the entire whole, of a homogeneous material, was extracted from a single mold.

After abandoning clients, family and practice in 1909, and running off to Europe ostensibly to publish his portfolio in Berlin with Ernst Wasmuth, it was not only his wife and family Wright fled, it was the Prairie house. It required years of careful observation while in Europe, California and Japan, for Wright to renew his spirit and reset his compass. Willey can’t be a bridge over what Anthony Alofsin termed Wright’s “lost years” when it is, in part, a product of them—a result of his study and experimentation, culminating in the discovery of something altogether new.

Although labels help us to understand the scope of his portfolio, it is dangerous to think of Wright’s work as a linear progression. To identify Prairie and Usonian periods is fine and necessary, but those names only represent definable periods of intense iteration for Wright, not the entirety of his ideas. As is true of the greatest of artists, Wright was always functioning on multiple channels simultaneously; designing landmarks, public buildings, grand estates and urban planning, all while solving the problem of affordable housing. Wright had the astounding ability to assimilate cultural and regional influences fused with the needs of his clients, then integrate them into his work without the slightest sacrifice to his own singular vision. Consider these four, sequential designs: the Hillside Drafting Studio, Willey House scheme 1 (project), Willey House scheme 2 and Fallingwater, all designed and executed between 1932 and 1935. Conceived one after the other, stylistically they could hardly be less similar. Instead, each is a response to specific conditions and circumstances. Each a reflection of site, budget, purpose, client, and artistic ambitions, all interpreted by the same artist and expressed clearly in his unmistakable voice.

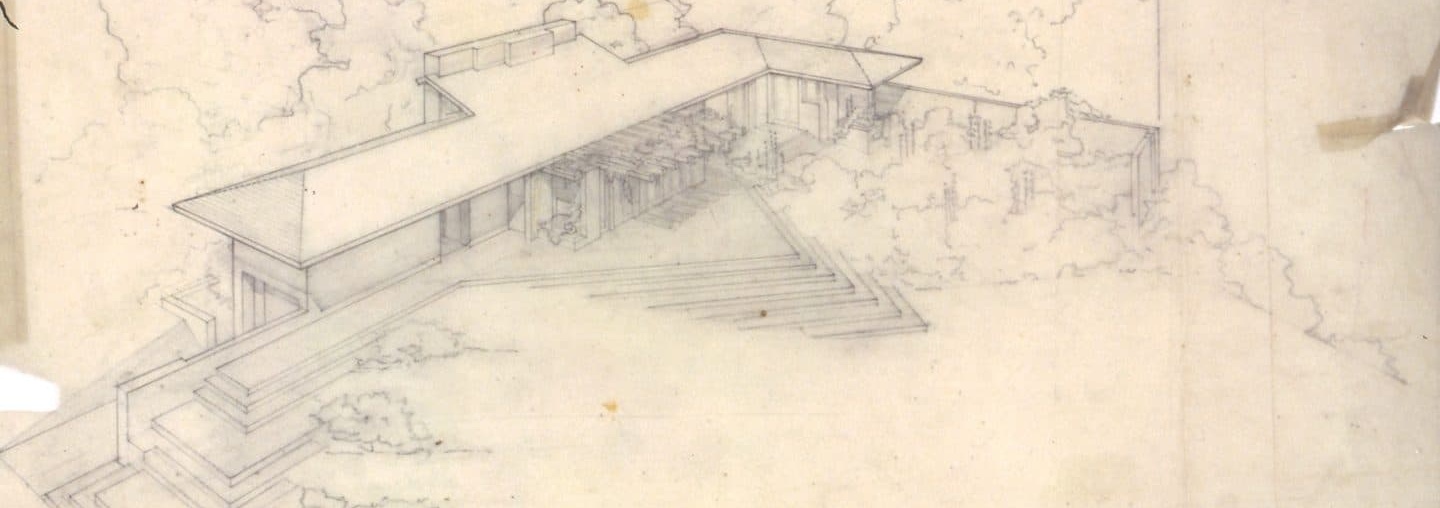

Willey House scheme 2 presentation drawing.

In Many Masks, Brendan Gill quoted Wright as saying he called the Jacobs house “Usonia One.” He also wrote that, “One might quarrel with Wright and say of the Jacobs house that it was Usonia Three having been preceded by houses designed in the Usonian vein for the Hoult family, in Wichita, Kansas, in 1935, and for the Lusk family, in Huron South Dakota, later in that same year.” He continues: “Both houses, which never got beyond the planning stage, owed a good deal to the Willey house of 1934, which must be then categorized as ur-Usonian, or even Premature Usonian. All such labels creating boundaries in a process that is by its nature without boundaries.” John Sergeant also credits these early projects and wrote that Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer declared the Hoult House of 1935 to be the first Usonian with John Howe in agreement.

If we are to consider unbuilt projects, then we must not overlook the first scheme for the Willey House, drawn in 1932. It is remarkably similar to the built work for Lloyd Lewis in Libertyville, Illinois, constructed in 1940. Wright explained the two-story design for Lewis, saying he raised it the off the ground to prevent dampness emanating from the nearby Des Plaines River, but it is essentially a reworking of Willey scheme 1. To my knowledge, no one has ever questioned whether the Lloyd Lewis House was Usonian. Sergeant would have classified it as a Raised Usonian.

To be honest, I can’t find any reasonable reference to associate the Willey House to the Prairie houses except in the correspondence between Nancy Willey and Wright when she suggests something like “Prairie House” for the name. Wright rejects her suggestion and responds simply with “The Garden Wall” as a suitable name.

Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer in his 2002 book published by GA entitled Frank Lloyd Wright Usonian Houses, gets the last word here: “The Usonian house has its origin in the Willey House of 1932. Here are found two elements that anticipate the final system of four years later: brick walls that rise directly from the ground rather than from low concrete platforms, and lapped board parapets. The first design proved, however, too costly, and the second design was ultimately built. This second design for Willey introduced another innovation that would come to characterize the Usonian house: the kitchen was open to the living-dining space, and would eventually be labeled ‘the workspace.’”

However we deem to categorize the Willey House, one thing is certain: This commission was the spark that ignited the conflagration of Usonia, a guiding light that illuminated the final phase of Wright’s illustrious career. Eugene Masselink said “Nancy’s house was the plow that broke the plains.” The house, without question represents a paradigm shift in Wright’s thinking, one that allowed him to reinvent himself at age 65. Circling back at long last to the story, let me say, my conclusion is that the idea of a bridge between periods is hard one to support. So, at a loss for a better conclusion I’ll leave you with the words of Robert Plant from a funky ditty entitled The Crunge: “Have you seen the bridge? I ain’t seen the bridge! Where’s that confounded bridge!?”