Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Museum director Hilla von Rebay sought a “temple for the spirit” in which to house Solomon R. Guggenheim’s growing collection of modern art.

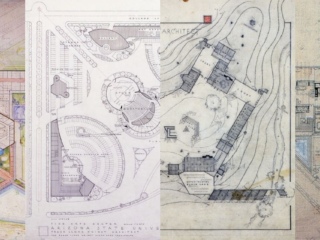

She wrote Frank Lloyd Wright in 1943, saying: “I need a fighter, a lover of space, an originator, a tester and a wise man – Your three books, which I am reading now, gave me the feeling that no one else would do.” Wright, who had never received a significant commission in New York, vowed that his creation would “make the building and the painting an uninterrupted, beautiful symphony such as never existed in the World of Art before.” Sixteen years later—following over 700 sketches, countless meetings, Rebay’s directorial replacement and the death of both Guggenheim and Wright—the architect’s self-described “archeseum” was unveiled. An exceptional icon of the 20th century, the Guggenheim launched the great and continuing age of museum architecture. Wright’s design declared that a collection’s physical home could be as crucial a part of the museum experience as the work itself.

Few buildings have inspired the level of controversy generated by the Guggenheim Museum. In sharp contrast to the typical rectangular Manhattan buildings that surround it, Wright’s museum resembles a white ribbon curled into a cylindrical stack that grows continuously wider as it spirals upwards towards a glass ceiling. Boldly claiming that his museum would make the nearby Metropolitan Museum of Art “look like a Protestant barn,” Wright’s “thoroughbred” of organic architecture dispensed with conventional museum design. An intensely cinematic helical spiral ramp climbs gently from ground level to a skylight at the top. Dismissed by contemporary critics as a “washing machine,” an “imitation beehive,” and a “giant toilet bowl,” Wright’s design was even decried by avant-garde artists, who claimed that such architecture would compete with the artwork. Ultimately, the Guggenheim liberated museum architecture from its conservative constraints. Wright’s museum took an active role in shaping the experience of looking at art and set a powerful precedent for which the modern museum remains profoundly indebted.