S.C. Johnson Administrative Complex

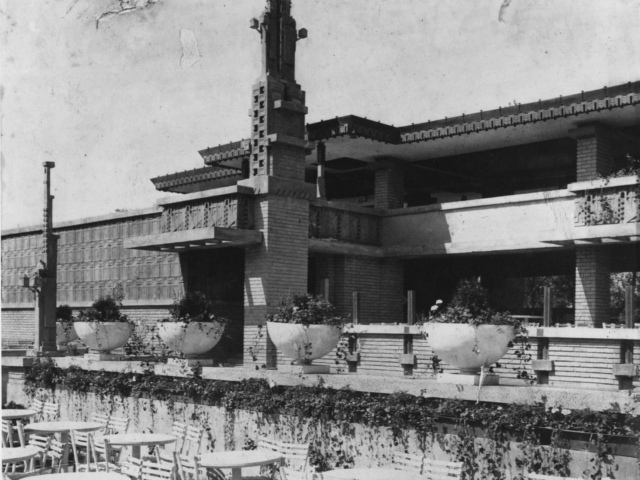

When the Johnson Wax Administration Building was completed Life magazine called it the greatest innovation since the skyscraper: “a truer glimpse of the shape of things to come.” Like Wright’s Larkin Administration building of 1903, Wright desired to build an exhilarating work environment, even suggesting that it be moved out of the bleak industrial zone of Racine for which it was planned.

When Herbert Johnson refused to turn his back on his company’s hometown, Wright designed the building without windows, explaining that as “nature was not present” in the environment, his design would “recreate nature” on the interior. The result, Wright promised, would be like working in a pine forest glade, with fresh air and sunlight all of the time. Wright achieved his vision with the help of two important innovations: steel mesh-reinforced concrete and glass tubing. The concrete allowed him to build slender white columns that rose tendril-like from their nine-inch bases to eighteen-foot-wide circular concrete “lily pads” that support the roof. The tubing allowed much of the roof and clerestory to filter perfectly diffuse light between the lily pads, creating a space that, without traditional windows, is the very essence of light. Due to the fact that the available technology could not properly seal the glass tubing, the roof leaked every time it rained. Herbert Johnson took to keeping a bucket on his desk to catch the drops.

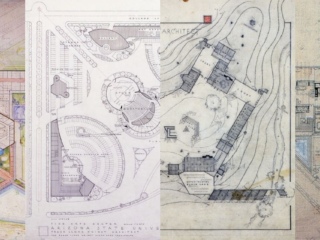

The construction of the Johnson Wax Administration posed significant challenges and costs, originally budgeted at $200,000, kept rising. “First, Frank Lloyd Wright was working for me,” Johnson recounted: “Then we were working together. Finally, I was working for him.” Despite spending some $900,000 to see his headquarters finished, Johnson was so enamored of Wright’s genius that he would go on to employ Wright to design both his personal home and the new headquarters for the company’s research and design division. The resulting fourteen-story research tower is connected to the main building by a covered bridge. Reinforced concrete slabs, cantilevered from the building’s central core, form the alternating square floors and circular balconies. Though the Research Tower is no longer in use because of a change in fire safety codes, an extensive restoration completed in 2013 has enabled the tower to be open for public tours for the first time in its history.