Living in Brilliance

Richard Bradley | Apr 22, 2022

Original resident of Wright’s Usonia Roland Reaisley spoke with journalist, author, and fellow Usonia resident Richard Bradley about commissioning a Frank Lloyd Wright house, living in Usonia, and the experience of residing in a Wright-designed structure for over 70 years.

There’s a story that Roland Reisley likes to tell about having Frank Lloyd Wright as his architect. At the time—this was in 1951—Reisley was a young engineer, and he and his wife, Ronny, had, to their great surprise, managed to secure the 84-year-old Wright to design a new home for them in Usonia, the idealistic collective in Pleasantville, New York, that Wright had designed in the late 1940s. Newly married, the Reisleys were in their mid-20s, just starting life together. In his job as a sound engineer in Manhattan, Reisley was making $6,500 a year—“a pretty good salary at the time,” he says. So Reisley had proposed to Wright a budget of $20,000. Wright counter-proposed $30,000. Reisley accepted, thinking that even if the house managed to go to $35,000, he could come up with the money. “I felt that somehow with mortgages and this and that, we should be able to manage.”

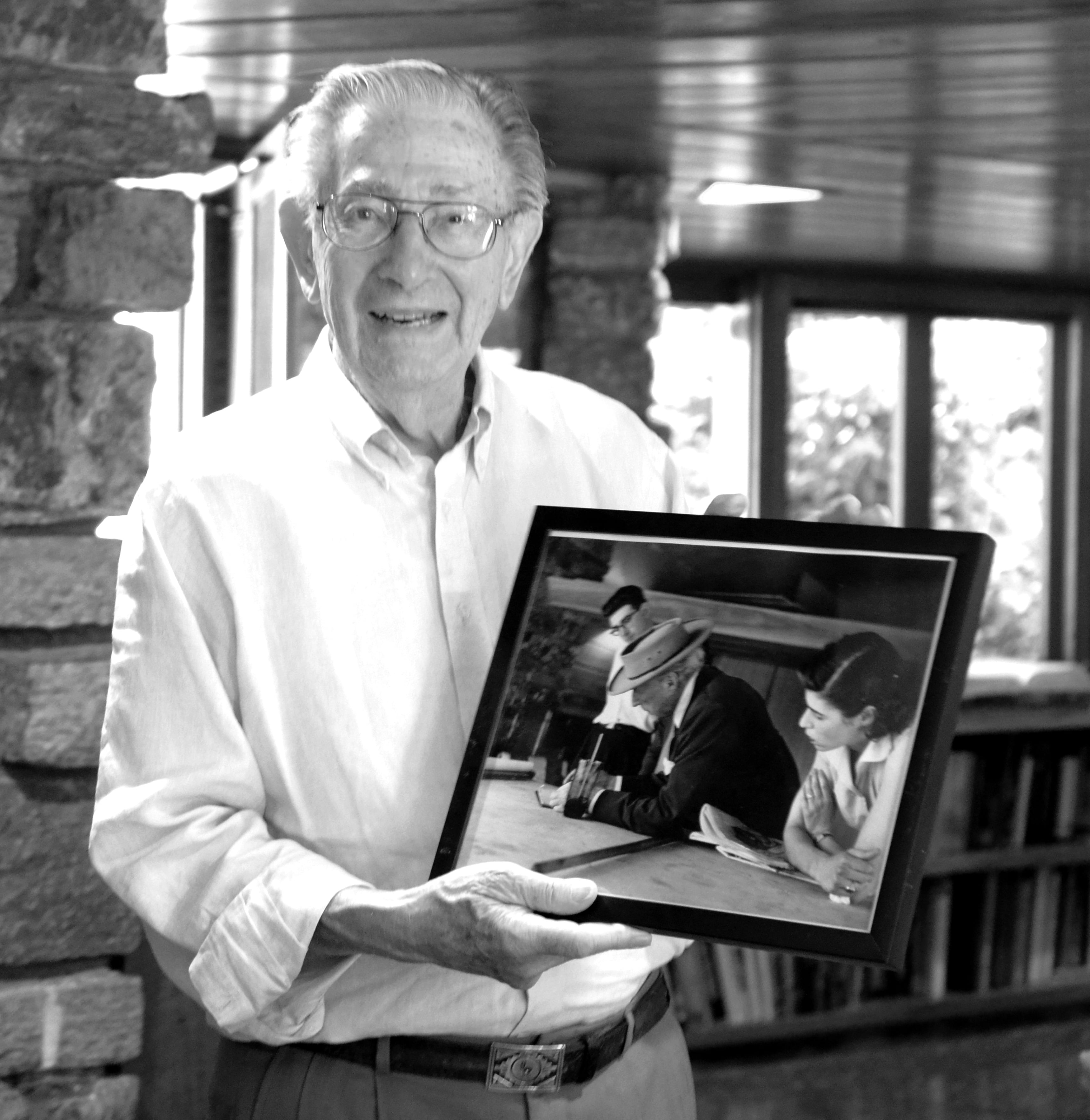

Roland and Ronny Reisley with Frank Lloyd Wright at the Reisley House

That fiscal ceiling didn’t last long. “Once we started building, everything was too expensive,” Reisley recalls. “The costs were just utterly beyond what we had prepared for.” (The original house would cost $50,000, even before a Wright-designed addition five years later.) “So,” Reisley admits, “I complained to Wright. And he said, ‘Well, Roland, building this house is one of the best things you can do. Stop for a while, if you must. But keep going. If you run out of money, pay me when you can. I promise you’ll thank me.” Reisley took the advice.

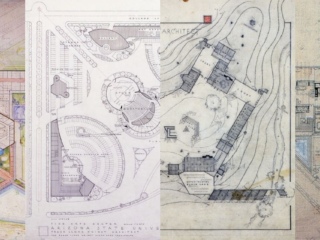

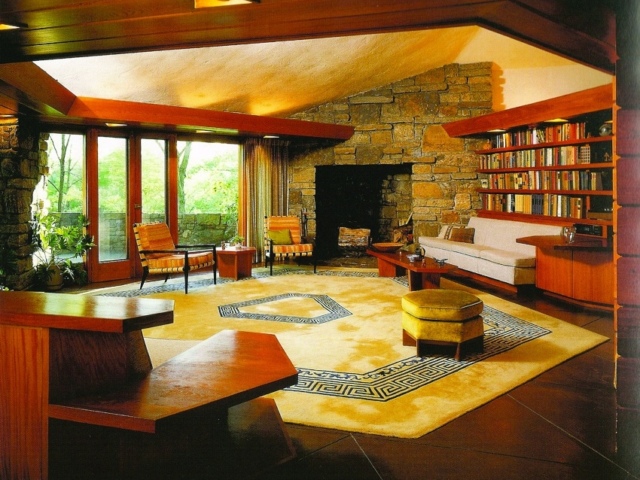

I met Roland in 2013, when my wife, our one-year-old son, and I moved into a house diagonally across the street from his in the hilly, wooded community of Usonia. Roland invited the three of us into his home and gave us a tour: the central theme of equilateral triangles with four-foot sides; the narrow foyer that opened into a sun-filled living room with built-in furniture and dominant fireplace; the master bedroom with one wall of rough granite mined from a local quarry; its adjacent study, cozy and perfect; the recessed, triangular overhead lights, 107 of them in all; a long row of additional bedrooms. As we walked, my son careened insistently into every room, touching everything he could reach. While my wife and I tried not to obsess about the damage our child might inflict, Roland seemed not at all concerned. He told us about the history of Usonia—how a group of middle-class New Yorkers came up with the idea for a cooperative community in post-World War II America, then painstakingly raised the money to buy a 110-acre piece of land in the woods near Westchester’s Kensico Reservoir and recruited Wright to design the site. We had known a bit of the story when we bought the house, but as Roland spoke, we started to better appreciate how fortunate we were to stumble upon this fascinating community. After all, during Usonia’s first 40 years, only 12 homes changed hands—and six of those transfers went to the children of original homeowners. This was an exceptional place.

‘Usonia’s houses were supposed to be of the land, not on the land. Integrated, as if they grew out naturally.’

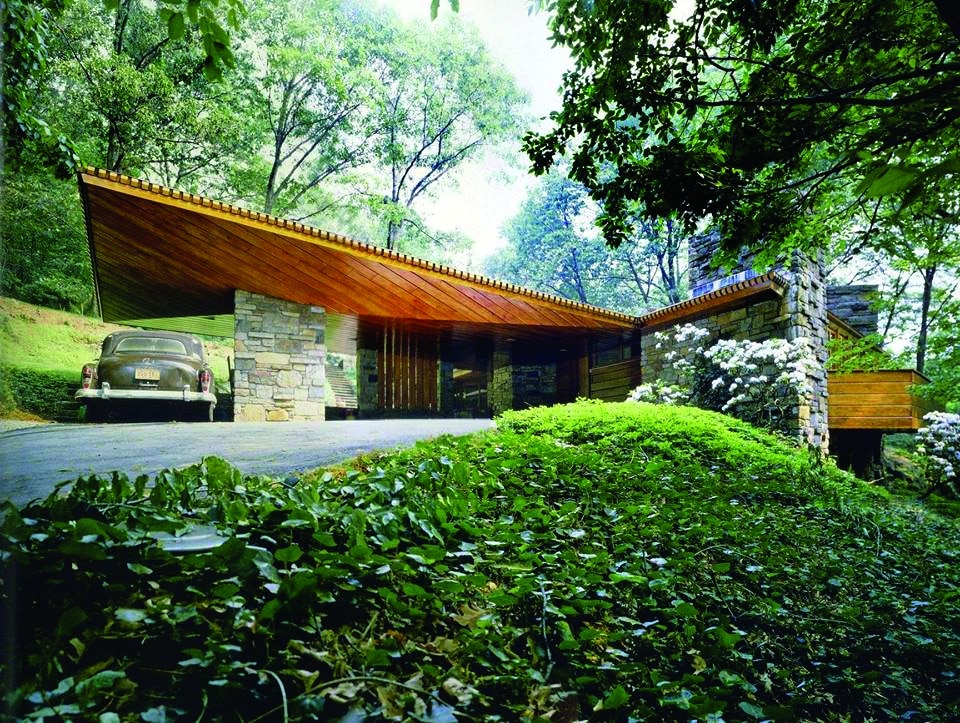

As we were finishing our visit, Roland gave my boy a plastic toy car big enough for him to ride in, which had once belonged to Roland’s son. My son—and, later, his brother—loved to ride that car down a small, sloping hill on our property across the street. From there, we could look up and appreciate the masterpiece that Wright had designed for Roland—its carport arching skyward, like some sort of futuristic jet wing; a row of windows peeping out of a hillside; the patio rising from a dramatic boulder, its bold stone corner jutting like the prow of a ship.

Reisley House, photo by Roland Reisley

Though my marriage ended in the seven years since, I felt grounded in Usonia and stayed here. I’d come to value my view of Roland’s house even more deeply; it’s a bolt of inspiration as the sun rises behind it. But until recently, I’d never spoken to Roland about what it is like to actually live there, to be surrounded by a work of genius as one’s everyday milieu. How, after 70 years in the only house he’d ever owned, did he feel about it all? Given that, at age 96, Roland is likely the last client of Wright’s living in the building Wright designed for him, it seemed a timely question. So a few weeks ago, I walked across the street to talk with my neighbor. Sitting in a wooden chair next to his living room’s enormous fireplace, the floor-to-ceiling windows behind him looking out on the patio, Roland shared his experience of living in brilliance.

In 1950, Reisley was 26 years old and living in a one-bedroom apartment at 126 West 85th Street in Manhattan. A sound engineer, he was intrigued by technology and innovation and was “completely gripped” by the futurism of the 1939–1940 World’s Fair. But he knew relatively little about Frank Lloyd Wright, other than having seen a model of Fallingwater and another of Broadacre City, Wright’s concept community, when it was displayed in Rockefeller Center in 1935. In 1950, he married Rosalind Sachs, known as Ronny, and the two began thinking about starting a family and putting down roots outside of Manhattan. “We were looking at suburbs here and there,” Reisley recalls. “If we saw something that we liked, we couldn’t afford it. If we could afford it, we didn’t like it.” A coworker of his father’s told Reisley about a new cooperative community in northern Westchester that was building affordable houses. So Roland and Ronny headed north to take a look at Usonia, where only nine or ten houses had been completed and the roads were unpaved. “We were greeted with open arms,” Reisley says. “The people here were so enthusiastic about the project, so committed to what they were doing.” The Reisleys were convinced; they took some money they’d been given as a wedding present, became members of the new cooperative and picked a plot of land. The question was, who would design their house? Usonia founder David Henken mentioned that Wright would be soon visiting to check on Usonia’s progress, and “he might want to design a house for you.” The suggestion took Reisley aback. “We didn’t dream of asking Frank Lloyd Wright,” he explains. “That was something ordinary people didn’t do.”

Reisley House living room, photo by Roland Reisley

Nevertheless Reisley called the architect, and Wright seemed amenable. On his next visit to Usonia, Wright visited the Reisley’s plot, a wooded hillside near the southern entrance to the community. “We told him we wanted to build on top of a hill,” Reisley recalls. “And he said, ‘No, no, no, no—that’s just a house on a hill. A house should be of the hill.’” Because, Reisley came to appreciate, “Usonia’s houses were supposed to be of the land, not on the land. Integrated, as if they grew out naturally.”

His house isn’t a museum, it’s a home, and in that regard it has worked very well, even as Roland’s family grew and changed.

At Wright’s suggestion, the Reisleys wrote him a letter specifying what they needed from their potential house—basically, a home in which they could start a family, and perhaps even fit a grand piano somewhere. “I remember telling him we liked cantilevers,” says Reisley with a laugh. “I wonder where we got that idea.” Reisley found Wright surprisingly easy to work with, not at all the imposing, rigid figure the architect is sometimes remembered as. When, during the drafting process, Reisley had some quibbles—the lack of a broom closet, for example—he nervously raised the issue with Wright. Relax, Wright told him. “You’re my client. I’m your architect. I’ll redesign your house as many times as I have to in order to satisfy your needs.” At another point during construction, Wright asked Reisley for a payment. “I said, ‘Gee, Mr. Wright, I’m almost broke, we have bills due on the house.’ He said, ‘Finish the house—pay me later.’” Construction began in October 1951. Roland and Ronny moved into the house in the spring of 1952.

I asked Roland what he remembered about moving in. After all, he is likely the last person on the planet who was the first person to move into a Frank Lloyd Wright home. Perhaps because he’d been so involved during the construction process, Roland said, he didn’t have specific memories of his first impressions of inhabiting the house. Rather, it was the accumulation of awareness that he remembers. “I came to realize—10, 15, 20 years later—that there was not a day in my life when I was not aware of seeing something beautiful. Conscious of it. And that’s still true.” Roland gestured to a cypress wall off the living room. “I look around and I’m looking at that wall, and the angle of it and the cypress wood. It’s beautiful.”

Reisley House exterior

Reisley House exterior

I mentioned that the cypress looked virtually brand new, and Roland laughed and said that it was “very, very, very durable—the wood was washed and waxed once in these 70 years.” There’s a larger point there that clearly matters to the homeowner: His house isn’t a museum, it’s a home, and in that regard it has worked very well, even as Roland’s family grew and changed. “In terms of meeting the needs of a young newlywed couple, to young parents, to teenagers, to empty nest, to retirement and old age, it has worked—it has functioned very satisfactorily over its lifetime,” Roland says. “I think that’s a significant observation. A house, after all, has got to function. It’s got to meet the needs and the desires of the people who live in it. And it did.”

Ronny Reisley passed away in 2006, and some years later Roland was joined in the home by a new life partner, Barbara Coates, herself a longtime Usonia resident. Barbara, now 84, joined Roland and me as we spoke, and I asked her about her experience of living in the house. “It’s hard for me to separate the house from Roland,” she admitted. “That was the primary thing that changed my life—living with Roland. Living in a Frank Lloyd Wright house, that was secondary to me.” And when she moved in, she confessed, she worried that she would do something to damage or mar the house, even though Roland assured her not to worry, these things happened in any home. Eventually, she relaxed into her new environment. “Now I think it’s a very livable house,” Barbara says. “It’s a very comfortable place to be. It happens all the time that I see something different and something new.” The house, she said, “is surprisingly beautiful all the time.” I took a moment to appreciate that phrase, “surprisingly beautiful all the time”—what a remarkable way to experience life.

When I asked Roland to explain how this everyday beauty had affected him, he chose his words carefully; my sense was that he didn’t want to indulge in oratory and abstraction. That isn’t his style—he’s still an engineer, fascinated by the way things are put together and the way they work, form and function. But also, I think, he feared making his home sound like some sort of temple, a place to be venerated from an emotional distance. After all, perhaps the most important principle of Usonian homes was that their beauty could be affordable, accessible. Living in beauty could be an everyday thing. In fact, it should be.

“Seeing this beauty all the time … it feels good,” Roland said simply. “During much of the year, the sun shining through the carport louvers creates a kind of carpet, and it’s beautiful. I see it when I go out to get the paper and I think, ‘Isn’t that lovely?’ When we return from a walk and there’s the house—‘Gosh, it’s a beautiful house.’ I like looking up at the house and seeing it growing out of that boulder. Every now and then, I’ll go down to the street and rephotograph it, to see if I can get the perfect photograph.”

Reisley House, photo by Roland Reisley

He can’t prove it, but Roland thinks the experience of living in the home has contributed to his longevity. “The neuroscientists tell us that, if you live with a sense of beauty, it reduces tension. The awareness of a beautiful environment reduces tension and stress; this is essentially physiologically healthy and beneficial.” He shrugged, looking slightly uncomfortable at making a claim that may sound grandiose. “It’s pure speculation,” he admitted. “But … it’s nice to be aware of living a life and being aware of beauty. And it’s nice to think that maybe it really does have something to do with longevity.”

After all, perhaps the most important principle of Usonian homes was that their beauty could be affordable, accessible. Living in beauty could be an everyday thing. In fact, it should be.

I asked Roland to share his feelings about different elements of the house. He rose from his chair and led me through the small corridor to the master bedroom, which has no furniture other than a bed that looks out toward built-in drawers and a row of windows. The closets are built in, and there are no lights other than the recessed triangles overhead. (In fact, Reisley says that the placement of the overhead lights is so exact, there’s no need for additional lighting, and so there are no lamps in his house.) On the window ledge sits a framed picture of Frank Lloyd Wright, standing in the exact spot where the picture now rests.

Roland Reisley in 2017, photo by Mark Hertzberg

Roland gestured to the side of the bed nearest the granite wall. “I sleep on that side of the bed,” he said, “and when I wake up and look at the stone wall, I like the stones. It’s not drywall. I look toward the pull-outs [underneath the windows] and I’m aware of looking outside and the trees growing up. I do some exercise on the floor, push-ups and sit-ups, and I’m looking up and I see the wood and the miter and the angle of the ceiling above, and I’m conscious that even that trivial detail looks nice.” As we exited the bedroom and walked past the small study, Roland said that even when he didn’t enter the room, he was aware of its beauty. “I’m talking about my sense as I walk by,” he explained. “A glance over there, and I’m conscious of the fact that I like what I see.”

I hated to change the subject to something less beautiful, but it felt important to ask Roland how he planned to preserve the house after he is gone. He said that he planned to create a preservation easement that would keep the house from being significantly changed. “I will require that the house must accommodate the needs of people who live here,” he explained. “If they have to make some changes”—he mentioned new kitchen appliances, or replacing the aging Formica on the kitchen counter—“I don’t want to prevent that from happening.” But, he added firmly, “the essential design has to be preserved. These houses … they’re works of art. They should be kept.”

I thought again of how Roland had once complained to Frank Lloyd Wright about the expense of building. “Keep going,” the architect had said. “You’ll thank me.”

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2021 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly. The Quarterly magazine is a member-exclusive benefit. To receive current and future issues, become a member today.

RICHARD BRADLEY is the Editor-at-Large at Worth Media. He is a resident of Usonia in New York, living across the street from Roland Reisley in a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice, Aaron Resnik.